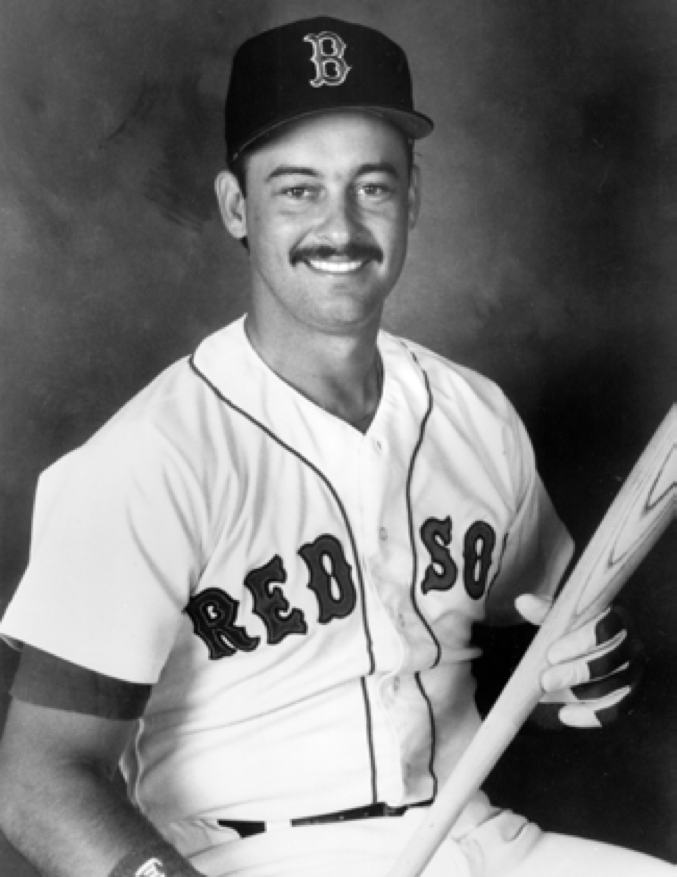

Mike Greenwell

In mid-September of 1988, the Boston Red Sox were closing in on an American League East Division title. With 18 games left on its schedule, Boston held a 4½-game lead over New York and Detroit. The Red Sox were in the midst of a nine-game homestand, having thus far taken four of five games from Cleveland and Baltimore. They would close the homestand with three more games against the Yankees. Not only were these games with Boston’s biggest rivals, but there was a lot riding on the series.

So as they prepared to take on the Orioles on September 14, looking for a sweep in the series, it may have been easy to be caught peering ahead. The Orioles, after all, had set an American League record in futility, as they lost 21 straight games to begin the season. Boston had already taken 8 of 12 games from Baltimore thus far. But the Red Sox had once been floundering, too. At the All-Star break their record stood at 43-42 and they were nine games behind first-place Detroit. John McNamara was replaced as manager by third-base coach Joe Morgan. After the break, Boston won 19 of 20 games to close to a tie with the Tigers on August 3. Was it a shrewd move by the front office, or perhaps happenstance? The one constant throughout the whole season was the consistent play of Mike Greenwell.

Greenwell was putting up some heady offensive numbers. He was hitting .334 with 20 homers, 109 RBIs, and 36 doubles heading into the game with Baltimore. With Boston trailing 2-0 in the second inning, Greenwell deposited a fastball over the Baltimore bullpen for his 21st home run of the season to slice the lead in half. In the fourth inning Greenwell doubled and eventually scored on Jim Rice’s fly ball. The Red Sox scored two runs in the frame to seize a 3-2 lead.

Greenwell led off the bottom of the sixth inning with a triple to left field. Left fielder Larry Sheets appeared to have a bead on the baseball, but it dropped behind him near the scoreboard. Greenwell legged it to third base. Baltimore manager Frank Robinson, perhaps showing his frustration over an already long season, was not pleased with the official scorer’s ruling of a triple. “What is this?” said Robby. “Christmas? They giving away triples around here?”1 Greenwell scored on a sacrifice fly by Ellis Burks, and the Red Sox now led 4-3.

“I knew I needed a single for the cycle,” said Greenwell. “Somebody jokingly asked me what I would do if I hit one in the gap. In a one-run game? I’d get as many bases as I could.”2 Greenwell singled to right field in the eighth inning, to cap his 4-for-4 day. All his hits came off Baltimore starter José Bautista. Greenwell was excited about his accomplishment. “You all saw how I felt,” he said afterward. “I had my fist clenched before I reached first base. When I was on the radio after the game, Ken Coleman and Joe Castiglione told me that hitting for the cycle is rarer than pitching a no-hitter. This is definitely one of my biggest thrills in baseball.”3

On his triple, Greenwell said, “When I first hit it I thought it might be caught. Then I saw he was having trouble with it so I put my head down and kept running hard. Once I saw it on the ground, I put my head down and just kept running.”4 That is Mike Greenwell in a nutshell; he was always hustling and never gave up on a play.

Michael Lewis Greenwell was born on July 18, 1963, in Louisville, Kentucky. He was one of seven children (two boys, five girls) born to Leonard and Martha Greenwell. When Mike was 5 years old, the family relocated to Fort Myers, Florida, where Leonard was a contractor for United Telephone. As a boy Greenwell spent many days hanging around Terry Park in Fort Myers, the spring-training home of the Kansas City Royals. His favorite player was George Brett, and he wanted to emulate his hero by becoming a third baseman.

His baseball coach at North Fort Myers High School, Ted Ferreira, was impressed with Greenwell’s ability as early as his sophomore season. “The thing I remember best about him is his eye-hand coordination,” he told the Boston Globe. “In three years he must have struck out only 10 or 12 times. When it came to being a leader, he was it. He would lead our team workouts, and if anybody tried to beat him on the lap around the park, Mike would sprint and beat him.”5

Greenwell was also the quarterback on the football team, and had great speed and a terrific arm. Although he did not play his senior year, he was offered a scholarship to the University of Miami. “They wanted to give me a shot at quarterback or wide receiver,” said Greenwell. “Who would have I competed against at QB? Vinny Testaverde. Who knows what would have happened?”6

Boston chose Greenwell in the third round of the amateur draft on June 7, 1982. He was signed by scout George Digby. Instead of heading to Miami, Greenwell joined the Elmira Pioneers of the New York-Penn League. The Pioneers positioned Greenwell at third base (48 games) and second base (24 games), but as he escalated through the Red Sox farm system, he was tried at both his natural position of third base and the outfield. In 1985 and 1986 Greenwell began the season at Pawtucket of the Triple-A International League. At the end of both years, he found himself in Boston.

Greenwell made his major-league debut as a pinch-runner for Jim Rice in the second game of a September 5, 1985, doubleheader against Cleveland. However, his capable work at the plate was not that far away. Greenwell’s first hit in the big leagues was a two-run homer on September 25 at Toronto. The 13th-inning round-tripper won the game for Boston, 4-2. He hit another two-run blast the next night, and a solo shot on October 1 at Baltimore. His first three hits were all homers. “I remember I was driving to the park about a week ago with Marc Sullivan and I kept saying that I wanted at least one hit, that’s all, just one hit,” said Greenwell. “I couldn’t dream this would happen. It’s unbelievable.”7

Perhaps because of Greenwell’s power surge, the Red Sox didn’t wait as long to call him up in 1986. He knocked out 18 home runs for Pawtucket before being recalled in late July. He showed plenty of promise, batting .314 for the Red Sox. Boston captured the AL East Division for the first time since 1975. Greenwell was added to the postseason roster, serving as a left-handed bat off the bench. The Red Sox defeated California in the ALCS in seven games. The Angels had a 3-games-to-1 lead, but Boston came roaring back, winning three straight games to claim the pennant. The turning point was Game Five, when the Red Sox scored four times in the top of the ninth inning on two-run homers by Don Baylor and Dave Henderson.

As dramatic as the ALCS was, it paled in comparison to the World Series. The Red Sox’ opponent was the New York Mets. Boston won the first two games at the Mets’ Shea Stadium, but then lost two of three at Fenway Park. They headed back to New York with a 3-games-to-2 lead, and seemingly had a firm grasp on the world championship after scoring two runs in the 10th inning of Game Six. But New York bettered them with three runs in the bottom of the frame to win and forced a Game Seven, which the Mets also won.

There was no stopping in Pawtucket in 1987 as Greenwell, who was also known as Gator for wrestling alligators in Florida, came north with the Red Sox after spring training. The Red Sox outfield was in makeover mode as Dave Henderson moved to right field to make room for Ellis Burks in center field. Henderson was later traded to San Francisco and Todd Benzinger took over in right. Greenwell became the fourth outfielder, and platooned at DH with Don Baylor. By the end of the season, he was the starting left fielder; Jim Rice was in and out of the lineup with hand and knee injuries. “My goal was to show people I can play, and I think I did,” said Greenwell. “I was brought along slowly, like I should have, showed I could hit right-handed pitching, and now my goal is to be an everyday player.”8 In what was his official rookie season, Greenwell hit 19 home runs, drove in 89 runs, and batted .328. “He can hit. There was never a doubt in anybody’s mind,”9 said McNamara.

Greenwell became the starting left fielder in 1988 as Jim Rice assumed the role of designated hitter. Gator had a lot to live up to, as he was following a long lineage of great left fielders, all of whom would one day be enshrined at Cooperstown. From Ted Williams to Carl Yastrzemski to Jim Rice, they combined for 48 straight years of stellar left-field play. Greenwell, who was being dubbed the New Green Monster, gave credence to that moniker with a big year in 1988. He was third in the league in hits (192), RBIs (119), and batting average (.325), and second in OBP (.416). The truth was that Greenwell trailed teammate Wade Boggs in all of these categories, except for RBIs. Boggs also led the circuit in walks, runs, and doubles. If there was an MVP candidate from Boston, it probably should have been Boggs. Nonetheless, Greenwell was touted as a strong candidate for the award, but finished second in the voting to José Canseco. The power hitter of the Oakland A’s became the first 40/40 man in major-league history, smacking 40 home runs and stealing 40 bases. Years later, when it was uncovered that Canseco was a steroid user and his play on the field was affected by them, Greenwell railed against the vote. “Nobody remembers who finishes second,” said Greenwell. “It cost me my legacy. There’s only so many guys who can walk around saying ‘I’m an American League MVP.’ It bothered me to lose to a guy who was using steroids.”10

The Sporting News named Greenwell to its All-Star and Silver Slugger teams in 1988. He was also recognized by the Boston Chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America as the Red Sox MVP.

After winning the division title in 1988, the Red Sox finished third in 1989, then won the title again in 1990. Both division-winning years, they were swept by Canseco’s Oakland team.

In 1988 and 1989 Greenwell was named as a bench player on the American League All-Star team. After the All-Star break in 1989, he posted the longest hitting streak of his career, 21 games from July 15 to August 20. He batted .361 during the streak, going 30-for-83. On September 1, 1990, Greenwell hit an inside-the-park grand slam off Greg Cadaret of New York. With the bases loaded and no outs in the fifth inning, Greenwell smashed a groundball just inside the first-base bag. Right fielder Jesse Barfield, trying to cut it off, lunged for the baseball, but missed it and it rolled away. Barfield fell and knocked his knee against the wall. Greenwell just kept motoring around the bases. “When’s the last time you saw that on a grounder?” said manager Morgan. “That may be a first in the history of the game. Call up Willie Wilson. If he hasn’t done it, nobody has.”11 Greenwell was one of only 11 Red Sox players to hit an inside-the park grand slam.12

After a .300 season in 1991, Greenwell’s 1992 season was cut short after multiple stops to the disabled list. He was placed on the DL in May with strained muscles in his right forearm, and again on June 22. On July 2 he had surgery on his right elbow to repair ligament damage and also had arthroscopic surgery on his right knee. He bounced back in 1993 to have another outstanding offensive year, batting .315, smacking 13 home runs and 38 doubles, and he drove in 72 runs.

In 1994 the four major league divisions were realigned into six. (Central Divisions were added to go with the East and West Divisions.) A wild-card team was added, creating another level of playoffs. But the players strike on August 11 washed out the rest of the season and the postseason. It also carried over to 1995, as that season was reduced to a 144-game schedule.

Boston had little trouble winning the AL East Division in ’95. Entering September, they held a 14-game lead over New York, and coasted through the final month to win by seven games. But they were swept by Cleveland in three games in the Division Series.

Greenwell injured the ring finger on his left hand in 1996, and missed all of May and June and the first half of July. He also battled a sore back and a bruised right foot. On September 2 at Seattle, Greenwell set a career high with nine RBIs, setting a record by driving in all the Boston runs as the Red Sox topped the Mariners in 10 innings, 9-8. “It was a career night for him,” said Mariners manager Lou Piniella. “It was a week’s work. Two weeks’ work.”13

The Red Sox offered Greenwell a one-year contract for the 1997 season, but he rejected it. “My time is done here,” he said. “It’s time to move on and I’m not coming back. It’s unfortunate, it’s sad, it doesn’t break my heart, but it sure makes it awful heavy.”14 Greenwell batted .303 in his 12 years with the Red Sox, and had 130 home runs, 726 RBIs, 1,400 hits, and 275 doubles. He led AL left fielders in assists in 1989 (11) and 1990 (12).

In 1997 Greenwell joined the Hanshin Tigers in Japan. But a foul ball off his right instep on May 10 resulted in a broken foot. After seven games, he retired for good. “After having the back issues and then turning right around and, after only six games, breaking my foot, I kind of felt that was a sign to move on, he said.15

And move on is precisely what Greenwell did. He served as a coach on Bob Boone’s staff in Cincinnati in 2001. A racing enthusiast, Greenwell joined the NASCAR Truck Series, and did some racing on his own. Todd Bodine, a Truck Series racer, mentored Greenwell. “Mike’s real good. He’s a racer who understands about driving,” said Bodine. “He’s won a lot of races and championships. He’s not a Jerry Glanville, a guy who came in here and wanted to be a racer and didn’t know what he was doing.”16

Closer to home in Cape Coral, Florida, Greenwell opened Mike Greenwell’s Bat-A-Ball and Family Fun Park since 1992. Cape Coral residents, he and his wife, Tracy, had two sons, Bo and Garrett. Bo was drafted in 2007 by Cleveland and also spent time in the Boston minor-league chain.

Greenwell entered public office in 2022 when he was appointed to the Lee County Commission by Florida governor Ron DeSantis. Following a diagnosis of medullary thyroid cancer, Greenwell died at the age of 62 on October 9, 2025.

When Mike Greenwell was selected to his first All-Star Game in 1988, it was also George Brett’s final appearance in the midsummer classic. Brett referred to Greenwell as a “Wade Boggs clone” for his hitting ability. From his perch among the trees at Terry Park, Greenwell would study Brett. As they were both left-handed hitters, Mike would take note of Brett’s swing. Once, as Brett was doing his sprints in the outfield, Greenwell yelled to him. Brett tossed him a can of his chewing tobacco. “I’ve still got the can,” says Greenwell. “I’m just going to save it. Nobody knows what it is but me.”17

Some might argue that Mike Greenwell was a “George Brett clone.”

Photo credit

Mike Greenwell, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 Boston Globe, September 15, 1988: 94.

2 Boston Globe, September 15, 1988: 94.

3 Boston Globe, September 15, 1988: 94.

4 Boston Herald, September15, 1988: 98.

5 Boston Globe, December 15, 1988: 84.

6 Boston Globe, December 15, 1988: 84.

7 Providence Journal-Bulletin, October 3, 1985.

8 The Sporting News, August 31, 1987: 14.

9 Baseball Digest, October 1988: 82.

10 New York Daily News, February 17, 2005.

11 Boston Herald, September 2, 1990: B1.

12 1995 Boston Red Sox Media Guide: 52.

13 Miami Herald, September 6, 1996.

14 Cape Cod Times, September 27, 1996: B-3.

15 USA Today Baseball Weekly, May 21-27, 1997: 49.

16 ESPN.com, May 23, 2006.

17 Baseball Digest, October 1988: 83.

Full Name

Michael Lewis Greenwell

Born

July 18, 1963 at Louisville, KY (USA)

Died

October 9, 2025 at Boston, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.