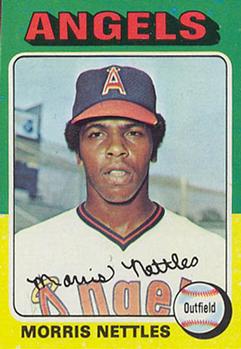

Morris Nettles

Speedy outfielder Morris Nettles played parts of just two seasons in the majors: 1974 and 1975 with the California Angels. He was only 23 when he played his last big-league game, though he hung on through 1982 in Mexico. Yet several decades later his remarkable skills and rapid rise from obscurity to the big leagues evoked marvel in the man who helped put Nettles on a path to The Show.

Speedy outfielder Morris Nettles played parts of just two seasons in the majors: 1974 and 1975 with the California Angels. He was only 23 when he played his last big-league game, though he hung on through 1982 in Mexico. Yet several decades later his remarkable skills and rapid rise from obscurity to the big leagues evoked marvel in the man who helped put Nettles on a path to The Show.

In the fall of 1969, during his first week as a teacher and head baseball coach at Venice High School in the Los Angeles area, Artie Harris sat in a meeting and listened while a colleague grumbled about the eligibility issues that plagued the school’s best athletes. Later that week, while directing a physical education class, Harris was left impressed by one such athlete. On the football field the teenager flung tight spirals 60 yards. On the basketball court he would leap to swat shots away before they reached the rim. Harris approached the young man and said, “Our first baseball practice is Saturday morning at Penmar Park. Nine o’clock.”1 The coach received no discernible reply. Two days later, when the new coach arrived to conduct his initial practice, a lone player sat waiting in the shade beneath a tree. It was Morris Nettles.

When the following week began, Harris checked with teachers to find out the sort of challenge it would be to get Nettles eligible for the varsity season in the spring. Their answers offered no optimism. Not only had Nettles missed a lot of school, he was a seventh- semester student in a three-year high school. Morris Nettles was a nice kid, clean-cut, soft spoken, and polite. But, the coach was cautioned, he was from Oakwood, a one-mile area in Venice that consisted of rundown apartments, poverty, and drug dealers. His parents, Morris and Hazel (née Clayton) had married as teenagers in Arkansas but split up before their son was ten. Hazel Nettles juggled raising the youth with work as a clerk.

Accepting that he would never have Nettles on his team, Harris phoned Norm Sherry, the older brother of a high school teammate, former Dodgers pitcher Larry Sherry. Norm Sherry was a coach with the California Angels and had been a big-league catcher. “Norm, I’d like you to take a look at this kid,” Harris said.2 Sensing reluctance, the high school coach offered, “I’ll buy you breakfast, and you can catch our practice after.”3 A week later, Norm Sherry left Penmar Park impressed. He had clocked Nettles from home to first base in a searing 3.7 seconds. The scout watched Nettles, who both threw and batted left-handed, beat out a two-hopper to second base. The player’s throwing arm was average, but he made good contact with the bat. Harris reminded Sherry that Morris Nettles’ skills were very undeveloped.

Just after New Year’s Day in 1970, Artie Harris was surprised to receive a phone call from Norm Sherry. The January draft was approaching. Nettles, by virtue of age, was eligible for selection. Sherry had tipped the Angels’ top area scout, Kenny Myers, to Nettles. The scout had worked Nettles out and liked him. Now, Sherry told Harris that the Angels planned to draft the player. “Artie, if we take him, that means you won’t have him for your season,” Sherry noted with concern.4 “Norm, he’s from a poor background. This is a good opportunity for him. Take him,” replied the coach.5

The Angels did. In the second round of the January 1970 draft, they selected a player who had never played an inning of high school varsity baseball and hadn’t played consistently in organized ball since Little League, six years before.

Once the Angels’ short-season rookie-league club began play, Nettles left the team’s brass in awe. The Southern Californian led the Pioneer League in hitting with a .369 average. He swiped 23 bases and was caught just once. The stolen-base tally was third best in the league behind Al Cowens and Jim Wohlford. Nettles legged out six triples to lead the Idaho Falls Angels. “When we ran our guys in the 60, the faster guys were around 6.8,” said the Angels Farm Director, Tom Sommers. “Nettles ran 6.1! He was a number-one runner. There were times when he wouldn’t run hard in the 60’s because he didn’t want to put up a time that might show up some of the other guys.”6

From amazement sprouted belief. One year later, in 1971 Nettles made the almost unheard-of leap to Class AA. His season began in the Midwest League (Class A), where, as chance had it, he would join two teammates who were also from Venice: John McGowan and Kenny Medlock. Medlock, who had known Nettles since the second grade and called his friend “Junior,” was also an Oakwood guy. The three became roommates and built a support system. While returning home from a series in Appleton, Wisconsin, Nettles turned to Medlock and, while munching on a hamburger, grinned and said, “You know, Kenny, I really like all this.”7

By mid-season the Angels’ Class AA farm club in Shreveport, Louisiana of the Dixie Association was left shorthanded when several players were ordered by the Army to report for summer camp. Nettles was promoted, and the mere 19-year-old finished with the highest batting average in the league, .338. In 1972 Nettles reconnected with Norm Sherry, who had become manager of the Angels Class AA farm club, the El Paso Sun Kings. There, Nettles led the Texas League with a .332 mark.

Reunited with Sherry again for the 1974 season in Salt Lake City (Triple A), Nettles didn’t stay long with the Angels’ top farm club. Eleven games into the season, Sherry delivered the news. There was an injury, and Nettles was going to the big leagues to fill in.

Barely off the airplane, Nettles was inserted as a seventh-inning defensive replacement during the Angels’ game in Cleveland. Two nights later, manager Bobby Winkles wrote Nettles’ name in the leadoff spot and started the rookie in center field. Like the rest of his teammates that night, Nettles was frustrated by Cleveland’s Gaylord Perry. The rookie struck out in all three plate appearances in a game in which Perry scattered four hits and struck out nine.

Winkles gave Nettles more playing time. A night after his first start, Nettles beat out two infield hits in a 7–2 Angels’ win over Boston. He reached base twice—on a walk and a single—the following night. Against Boston’s Bill Lee, Nettles’ speed forced an error and produced a double in a 4–2 Angels’ triumph. In a mid-May game in Texas, Nettles doubled twice off David Clyde.

Two weeks later, after he had spent 32 days in the big leagues, Morris Nettles was returned to Salt Lake City. Back in the Pacific Coast League the speedster went on a tear. On June 16, 1974, with the Angels mired in last place and the trade deadline at hand, Harry Dalton pondered myriad moves to try to shake up the team. The Angels’ general manager discussed 11 trade proposals with seven clubs.8 One consideration was to recall Nettles, who was hitting .330 in the minor leagues. When the deadline passed, Dalton stood pat. Two weeks later, Dalton finally made a move. This did not involve players. He fired Bobby Winkles and replaced him with the veteran Dick Williams.

The tenor of the Angels clubhouse changed. “He’s strict and harsh, particularly for young players,” said the club’s first baseman, Bruce Bochte.9 “This is a young club, which he hasn’t ever had,” noted Jerry Adair, one of Williams’ coaches.10 As soon as Williams took the manager’s office, the Angels lost eight of 11 games. The new skipper bemoaned his club’s lack of talent and urged Dalton to bring up some prospects from the minor leagues.

Throughout the summer months Nettles was among the hitting leaders in the Pacific Coast League. On August 22 the Angels’ center fielder, Mickey Rivers, suffered a hand injury. With a batting average at .328 and with 26 steals and sox triples, Nettles was the player summoned to replace the injured Rivers. After some initial struggles, his play in an August 31 game in Milwaukee drew Williams’ attention. In the second inning, Nettles singled in the Angels’ first run, then promptly sprinted for second base on an error. When Bobby Valentine poked a single to center field, Nettles flew home to give the Angels a 3–0 lead. In the fifth inning, Nettles beat out a bounding ball to second base and in the seventh inning added yet another single. From that day forward Nettles started every remaining game in the 1974 season.

During the final week of the season, Nettles was an uncelebrated hero in perhaps the most celebrated game of the year, Nolan Ryan’s third career no-hitter. It was Nettles who provided Ryan with run support. As the fireballer mowed down the Minnesota Twins, Morris Nettles singled home the game’s first run in the third inning. He promptly swiped second base, was awarded third on an interference call, then scored on a sacrifice fly. One inning later, Nettles came up with the bases loaded and laced a single to center field to plate the third and fourth runs in the Angels’ 4–0 triumph.

Nettles finished his first stint in the big leagues with a .276 batting average and 20 stolen bases in the 56 games in which he appeared. A day before the 1974 season concluded, Williams and Dalton huddled with coaches and scouts. Both were told there were no power-hitting prospects in the farm system. Taking stock of what he had inherited, Williams realized speed was the organization’s greatest asset. He decided to build his 1975 team around it. “Morris figures in our future,” Williams would tell Dan Hafner of the Los Angeles Times.11

As part of his plan, however, Williams wanted Nettles to change. The manager instructed the speedster that he was “to chop the ball into the ground.”12 Williams told a sportswriter, “One high bounce and he’s on base.”13 It was that directive that would unknowingly begin the end of Morris Nettles’ big-league career. “He’d been told all his life to try and hit the ball squarely,” Kenny Medlock recalled, “and now they’re telling him to try and hit the top half of the baseball. Dick Williams ruined him. He wasn’t good with young players. He really screwed Morris up.”14 His former coach recognized the problem. “It’s teaching,” Artie Harris explained. “We can all be told the same thing, but each of us hears something different.”15

When spring training began in February 1975, Morris Nettles was expected to be a key cog in the California Angels’ offense. “We’ve known all along that we’ll have to scrounge for runs,” Williams told Ross Newhan of the Los Angeles Times.16 Newhan wrote that “Nettles is the offensive key.”17 Williams planned to bat Nettles in the leadoff role and hit Mickey Rivers second. In the field the speedsters shared time in left field as well as center. “If Morris is on first, the first baseman will have to hold him on. That’ll give Mickey, who bats left-handed, a bigger hole on that side of the infield,” Angels coach Jimmie Reese explained to Dave Distel of the Times.18 Once the season began, however, Morris Nettles rarely reached first.

Nettles was cheered by 24,105 fans on Opening Day. Applause filled the evening air when Nettles singled to lead off the third inning and again when he ran down a hooking line drive hit by Vada Pinson. The loudest, an ecstatic roar, rose in the bottom of the ninth inning. With the Angels and Kansas City Royals tied 2–2, Nettles walked. He raced to second base on a bunt by Mickey Rivers, then to third when Tommy Harper looped a single into short center field. When Bruce Bochte drilled a line drive to right-center field, Nettles sprinted for home plate and beat Al Cowens’ throw to score the winning run.

The cheers, however, would wane. By the end of April, Nettles was struggling to fulfill Williams’ directive. His batting average was a paltry .216, and he had stolen just two bases. When Memorial Day rolled around, Nettles’ batting average was up, but just to .235, and the speedy outfielder had managed only five stolen bases.

By the middle of June, the Angels were wallowing near last place in the American League West. Nettles was batting only .229. The Angels’ struggles on offense were so bad that Texas Rangers manager Billy Martin cracked, “The Angels could hold batting practice in a hotel lobby and not break anything.”19 At that point, Williams’ patience with Nettles finally reached an end. The player was removed from the everyday starting lineup in favor of a minor-league call-up, Dave Collins.

Still, Nettles’ speed evoked awe. In the seventh inning of a June game against the New York Yankees, he produced a run from a steal of second base in one unbroken sequence. Inserted as a pinch-runner, Nettles lit out for second without prompting. As he neared the bag, he realized Thurman Munson’s throw would be wild. “I saw him (Fred Stanley) lean back in the direction he had come from. That told me the throw was wide, and I didn’t have to slide,” Nettles would later elaborate.20 Indeed, he kept right on running toward third base. Whitey Herzog, the Angels’ third-base coach, had noted that the Yankees’ center fielder, Elliott Maddox, was playing deep. Doubting Maddox could get to the ball quickly and make a strong throw, Herzog waved Nettles home, and the speedster scored easily to tie the game, 3–3. Dick Williams kept Nettles in the game. In the ninth inning Nettles lofted a sacrifice fly to shallow left field that brought Rivers home with the game’s final run in a 5–3 Angels’ win.

During the All-Star break Nettles married, exchanging vows with 18-year-old Sandra Williams. Their union would last five years and end in divorce with no children.

Over the final half of the 1975 season, Morris Nettles’ playing time dwindled. He went from Opening Day heroics to playing in just 17 games in the month of July, 12 games in August, and 10 in September. A final hurrah came on August 5, when he started and batted leadoff in the second game of a doubleheader in Chicago against the White Sox. Nettles had two hits and reached base twice on walks. He stole a base, and in two instances his speed landed him on third, only to be stranded there when the inning ended.

The game, however, would be the last in which Dick Williams would pencil Nettles’ name in his starting lineup. On December 11, 1975, at the winter meetings in Hollywood, Florida, Harry Dalton acted on his manager’s wish to eschew a running game for power. That morning Mickey Rivers was traded to the New York Yankees for Bobby Bonds. In the evening, Nettles was made part of a four-player trade with the Chicago White Sox that netted a former All-Star, Bill Melton. “We traded 92 stolen bases and picked up 47 home runs,” Dalton said. “We’re willing to trade speed for people who can hit the ball.”21

While the White Sox were especially keen to add speed to cover a spacious Comiskey Park outfield, few observers felt that Nettles would provide an answer. “Breaking into the Sox’ lineup with a role any more prominent than that of a pinch-runner would seem next to impossible,” wrote Richard Dozer in the Chicago Tribune.22

Indeed, after a poor spring Nettles was sent to the minor leagues, where he got off to a slow start. In June, with his batting average at .190, Nettles was shuttled from the White Sox Class AAA farm team to Cleveland’s affiliate in Toledo.

The 1977 season saw Nettles once again don an Angels uniform. This time, however, it was not with the team in Anaheim, but rather Puebla, Mexico. Nettles followed a bevy of former major-league standouts such as Alex Johnson, Blue Moon Odom, Dick Selma, and Jim Bouton to the Mexican League in hopes of catching the eye of a scout and earning a return to the big leagues. In Mexico, Nettles regained his batting stroke. By late July he was among the league leaders with a .344 average. Days later, a promising season came to an abrupt end. The Puebla Angels’ team bus was involved in an accident. Several players were injured. Nettles was hurt so severely that it brought an end to his season.

Nettles came back, and in 1979 was a key contributor to Puebla’s first Mexican League pennant in 26 years. Hopes of capitalizing on the success were quashed when much of the 1980 Mexican League season was cancelled by a players’ strike. In 1981 Nettles resumed his place among the top hitters in the Mexican League. By midseason he was hitting .320 and earned a place in the league’s All-Star Game.

In 1982 Nettles spent time with two teams, Campeche and Chihuahua. At the end of the season, factors that extended far beyond baseball affected his career. The Mexican government defaulted on its foreign debt, and the ensuing financial crisis caused the value of the peso to plummet and salaries for foreign players to fall. Rules were also changed within the Mexican League to reduce the number of foreign players per team. All of these things contributed to the end of the professional baseball career of Morris Nettles at the age of 30.

The years that followed his time in the game were dotted with struggles. Nettles suffered from financial difficulties and serious health issues. Friends such as Medlock, who was by then a successful actor with Moneyball and Another 48 Hours among his credits, provided help. Diabetes forced surgeons to amputate Nettles’ once fleet feet. On January 24, 2017, two days before his 65th birthday, Morris Nettles succumbed to the effects of diabetes.

For years those who were around Morris Nettles in the Angels organization marveled when they recalled his skills. Norm Sherry has called him one of the top athletes the organization ever signed. “One of the most phenomenal athletes I’ve ever been around,” added Tom Sommers. “He had so much raw athleticism. He was soft spoken, polite. Just an outstanding kid.”23

Acknowledgements

The writer gratefully thanks Artie Harris, Kenny Medlock, and Tom Sommers for their time, insights, and information which contributed to this biography, which was reviewed by Rory Costello and Gregory Wolf and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Telephone conversation with Artie Harris, February 28, 2017 (hereafter Harris conversation).

2 Harris conversation.

3 Harris conversation.

4 Harris conversation.

5 Harris conversation.

6 Interview with Tom Sommers, March 3, 2017 (hereafter Sommers interview).

7 Telephone conversation with Kenny Medlock, February 27, 2017 (hereafter Medlock conversation).

8 Jeff Prugh, “Angels Waste 14 Hits in 5-3 Loss.” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 1974.

9 Dave Distel, “Play Me, Don’t Trade Me.” Los Angeles Times, December 12, 1975.

10 Ron Rapoport, “Angels, at Last, Put Williams’ Patience to Test.” Los Angeles Times, July 17, 1975.

11 Dan Hafner, “‘Experiment’ Fails, Angels Lose, 1-0.” Los Angeles Times, September 6, 1974.

12 Dan Hafner, “Angels Need Speed and Defense to Be a Contender, Williams says.” Los Angeles Times, October 5, 1974.

13 Hafner, “Angels Need Speed and Defense to Be a Contender, Williams says.”

14 Medlock conversation.

15 Harris conversation.

16 Ross Newhan, “Speed, Pitching Angel Strength.” Los Angeles Times, April 7, 1975.

17 Newhan, “Speed, Pitching Angel Strength.”

18 Dave Distel, “The Chancellor. The Angels Consider Him a Real Steal.” Los Angeles Times, March 21, 1975.

19 Dick Miller, “Angel Swing to Power Nets Bonds and Melton.” The Sporting News, December 27, 1975.

20 Ross Newhan, “Angel Speed Puts Stop to Yank Streak.” Los Angeles Times, June 10, 1975.

21 Ron Rapoport, “Angel Offense: More Security With Bonds.” Los Angeles Times, December 12, 1975.

22 Richard Dozer, “Nettles, Spenser for Sox’ Melton.” Chicago Tribune, December 12, 1975.

23 Sommers interview.

Full Name

Morris Nettles

Born

January 26, 1952 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

January 24, 2017 at Venice, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.