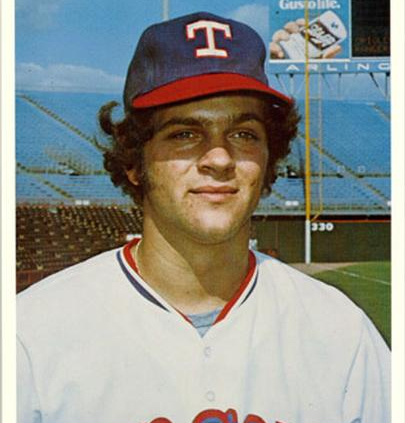

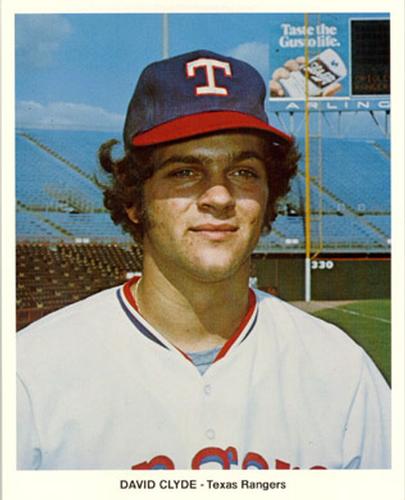

David Clyde

“It was like taking a kid and throwing him into brain surgery without going to medical school.” — David Clyde1

After being chosen as the top overall pick in the 1973 June amateur draft, left-handed pitcher David Clyde made the rare leap from high school to the big leagues with the Texas Rangers.2 The teenage phenom singlehandedly galvanized a fan base and saved a Rangers franchise that was in dire financial straits. It came at a cost, however. Skipping development in the minor leagues was likely detrimental to Clyde, who experienced flashes of success but never achieved consistency in the majors. He pitched 416⅓ innings over parts of five seasons with the Rangers and Cleveland Indians, registering an 18-33 record and 4.63 ERA.

After being chosen as the top overall pick in the 1973 June amateur draft, left-handed pitcher David Clyde made the rare leap from high school to the big leagues with the Texas Rangers.2 The teenage phenom singlehandedly galvanized a fan base and saved a Rangers franchise that was in dire financial straits. It came at a cost, however. Skipping development in the minor leagues was likely detrimental to Clyde, who experienced flashes of success but never achieved consistency in the majors. He pitched 416⅓ innings over parts of five seasons with the Rangers and Cleveland Indians, registering an 18-33 record and 4.63 ERA.

David Eugene Clyde was born on April 22, 1955, in Kansas City, Kansas. He was the first child born to Joseph Eugene “Gene” and Amy (née Glass) Clyde. Three more boys (Michael, Steve, and Henry) followed. Because of Gene’s job as an executive with Southwestern Bell, the family moved frequently during David’s childhood, eventually settling in Houston in 1969.

Clyde grew up idolizing Sandy Koufax and played baseball from an early age, honing his skills throwing to Gene, a former semipro player. Clyde’s standout ability to throw a baseball was evident early on. “There are certain gifts that God gives all of us … He blesses us all with certain unique abilities, and then it’s up to us to polish those skills,” said Clyde in 2023. “You have to train hard and work at it. I stood out from day one with the ability to throw hard.”3

Clyde’s passion was baseball, though he also lettered in basketball and football at Houston’s Westchester High School. As a freshman, he was already the best pitcher on the varsity team. His sophomore season included a perfect game against the defending state champions.4 Pitching for the Westchester American Legion squad that summer, he allowed only four runs in 83 innings while racking up 150 strikeouts.5 As a junior in 1972, Clyde amassed a 17-1 record which included three no-hitters and four one-hitters. In 121 innings pitched during the regular season, he whiffed 248 and allowed three earned runs for a microscopic 0.16 ERA.6 When Clyde faced off against Bellaire’s Jim Gideon in the state tournament, local sportswriters could not recall a matchup of better prep arms. Clyde proved to be fallible, however, issuing an uncharacteristic 10 walks in 3⅔ innings, which led to four earned runs and a loss.7,8

During his senior season, Clyde registered an 18-0 record, 0.18 ERA, and struck out a whopping 328 batters in 148 innings.9 His combination of an overpowering fastball, baffling curveball, and pinpoint control had scouts buzzing. The top pick in the 1973 June amateur draft belonged to the Texas Rangers, a distinction earned from owning the major-league’s worst record (54-100) in 1972. The Phillies, who had the second pick, sent scout Lou Fitzgerald to evaluate Clyde. Fitzgerald quickly realized there was no way the Rangers would pass on Clyde and left after three innings.10 On May 29, a contingent from the Rangers—including owner Bob Short, general manager Joe Burke, manager Whitey Herzog, and pitching coach Chuck Estrada—congregated in Dallas for the state tournament quarterfinal and watched as Clyde threw a no-hitter, further cementing his status as the consensus best amateur player available.

On June 5—the day of the draft—TV trucks lined up down the street outside of Clyde’s home. As expected, the Rangers selected him with the first overall pick, passing over the likes of Robin Yount and Dave Winfield. Clyde’s mid-90s fastball was already major-league caliber, leading to immediate speculation that he could skip the minor leagues and make the highly unusual leap from high school to The Show. The drastic jump was not unheard of in the 1950s under the “bonus baby” system of player acquisition but had not occurred since the draft was instituted in 1965.11 Gene handled the negotiations with Short, which resulted in a $65,000 bonus, $22,500 salary, and $7,500 roster bonus.12 Upon Clyde’s signing, Short decided his newly inked phenom would join the Rangers the following week. Neither Clyde nor his father insisted that he start in the majors. “There’s been some confusion over the years on that,” said Clyde in 2003. “We were not going to settle for anything less than a major league contract. That puts you on the 40-man roster.”13 Clyde wanted to ensure he got to the big leagues within three years or had the opportunity to go elsewhere.

The Rangers, in their second year in Texas after Short relocated the Washington Senators, had failed to capture the attention of north Texas in their inaugural season and were in desperate need of a gate attraction. They averaged 8,610 spectators at Arlington Stadium in 1972, and even fewer were showing up in 1973. Short regularly staged promotions in an attempt to lure fans, including Bat Night, T-shirt Night, Keychain Night, and even Pantyhose Night. “The solemn reality was that the Dallas-Fort Worth area was gaga over the Cowboys and the lame antics of a last-place baseball team were not inflaming fan response,” wrote beat writer Mike Shropshire in his book Seasons in Hell. Short personally had nothing to lose and a lot to gain at the turnstiles by putting his newly acquired teenage prodigy on the mound. Clyde joined the Rangers on the road and was thrust into action on the team’s next homestand. Herzog was against the idea from the start but acquiesced on a temporary basis. “I agreed to pitch Clyde two games, then farm him out to the minors, where he could build his arm and confidence over a couple of years,” wrote Herzog in You’re Missin’ a Great Game.14

On June 27, 1973, Clyde made his highly anticipated major-league debut versus the Minnesota Twins—only 20 days after he threw his last high school pitch. American League president Joe Cronin called it “the biggest debut since Bob Feller came out of Iowa.”15 A capacity crowd of 35,698—the largest in the Rangers’ brief history—packed Arlington Stadium for the Wednesday night affair. Another 10,000 were reportedly turned away.16 Belly dancers, lion cubs, and a large papier-mâché giraffe brought in from nearby theme parks added to the circus-like atmosphere. Clyde wore the number 32 in honor of Koufax, who also did not pitch in the minors before his major-league debut. Just before the game, Clyde received a telegram from the legendary pitcher that read, “Go get ’em, number 32.”17 Clyde was wild early, walking Jerry Terrell and Rod Carew on nine pitches to start the game, but then fanned the next three in succession. Clyde required 112 pitches to complete five innings, during which he walked seven, struck out eight, and allowed just one hit—a two-run home run off the bat of Mike Adams. The Rangers held the lead when Clyde departed, and Bill Gogolewski pitched the final four frames to secure the rookie’s first win.

Tickets sales were nearly as robust for Clyde’s second start five days later at home against the Chicago White Sox. “According to my calculations, on the extra gate receipts alone, in two starts I’ll make back David Clyde’s entire goddamn signing bonus,” remarked Short.18 Clyde breezed through the first four innings while striking out five and facing the minimum. The White Sox did not record a hit until Bill Melton’s leadoff single in the top of the fifth. Ken Henderson followed with a tapper back to Clyde, whose throw to second to start a would-be double play pulled shortstop Jim Mason off the base. The miscue led to two unearned runs later in the inning. A blister on Clyde’s pitching hand forced him out of the game after six innings with two walks and six strikeouts on his ledger. With the Rangers ahead, 4-3, he stood to be the winning pitcher, but the bullpen blew the game.

After seeing Clyde’s impact on attendance and impressive performance through two starts, Short decided to postpone the rookie’s demotion. As Herzog bluntly wrote in his memoir White Rat, “Bob Short was a fast-buck artist, a man who would do anything for a buck, a man who never had a long-term plan in his life. He had no earthly idea how to run a baseball team. With him, it was profit and loss and day to day.”19 Thus, Clyde remained in the Rangers’ rotation as the team hit the road. He was roughed up by the Milwaukee Brewers in his next outing but then rebounded to throw six innings of two-run ball against the Red Sox at Fenway Park. He struck out eight Boston hitters, including future Hall of Famers Carlton Fisk, Carl Yastrzemski, and Orlando Cepeda. Home plate umpire Bill Deegan told reporters that Clyde’s fastball was better than the heater of one of the game’s other top young arms—Vida Blue.20

Despite Clyde’s handful of competitive starts, the consensus from an informal survey of managers and executives was that he would benefit from time in the minors.21 Some believed he lacked a formidable off-speed arsenal to keep hitters honest and needed work on his pickoff move and infield defense. Though Clyde’s game clearly needed refinement, his maturity impressed Rangers catcher Ken Suarez, who had played with his share of bonus babies as a member of the Athletics. Suarez called Clyde “the most mature and adaptable 18-year-old I’ve ever seen.”22

Clyde, who was 6-foot-1 and 180 pounds with curly brown hair and sideburns, remained a major draw when the Rangers returned home. A crowd of 23,102 turned out on July 17 and watched the Brewers batter the southpaw for five runs on 11 hits in seven innings. Fans remained ambivalent when Clyde was not pitching; fewer than 6,000 attended the other two games of the series. Clyde recorded a no-decision versus the Tigers and then posted impressive back-to-back wins against the California Angels, limiting the Halos to one run over 14 innings. Through eight starts, he compiled a 3-3 record with a 3.31 ERA and 44 strikeouts in 49 innings. “For one month, Clyde was the best pitcher on my staff,” recalled Herzog. “He won three or four games right away, and every time he pitched at home, we’d draw 25,000 extra people. Short was delighted. I’d tell Bob it was time to send David out, but he’d say ‘no, just one more start.’ Pretty soon hitters caught up with David and started sitting on his fastball.”23

Clyde lost the feel for his curveball in August, which translated into a 1-3 record and 6.35 ERA in five starts. The rookie recognized the reason behind his struggles. “There are a lot of guys in the American League with a fastball much better than mine, but I don’t care who you are—if you can’t get the off-speed pitches over, all they have to do is lay back and wait for the fastball, and eventually they’ll bomb you,” said Clyde after a loss to the Orioles on August 27.24

Because of poor control and blister problems, Clyde failed to make it past the third inning in each of his first three September starts. Meanwhile, he had a new manager to impress. Herzog was fired on September 7 and replaced with Billy Martin, who had become available after being canned by Detroit. Herzog had protected Clyde by limiting him to 110-120 pitches or seven innings, whichever came first.25 Martin took away any restrictions for his final two outings. In Clyde’s penultimate start of the season—a Friday night home game versus the Angels which attracted a crowd of only 2,513—he pitched into the ninth inning but took the loss. He also lost his season finale versus the Royals and finished with a 4-8 record and 5.01 ERA in 18 starts.

One reporter calculated that Clyde’s 11 home starts in 1973—taking into account extra ticket sales, parking, and concessions—netted Short an estimated $528,000.26 Yet, when it came time to sign a contract for the 1974 season, Clyde was offered the same base salary he received the year before. “I’d have been happy with a $500 raise,” Clyde said, looking back. “Just to show they appreciated what I did.”27 He spent the offseason taking journalism courses at Texas A&M University and married his high school sweetheart, Cheryl Crawford.

Just before the start of the 1974 season, Short sold the Rangers to a team of investors led by plastic pipe manufacturer Brad Corbett at a price tag of $9.6 million plus the assumption of $1 million in debt.28 Meanwhile, Clyde went to spring training without the assurance of a roster spot but impressed Martin enough to make the opening day roster. Clyde slotted into Martin’s four-man rotation behind Jim Bibby, Fergie Jenkins, and Steve Hargan. The 19-year-old hurler came out of the gate hot, registering a 3-0 record and 2.43 ERA through his first six starts, including three complete games. From there, things quickly went south. Clyde failed to make it through five innings in six of his next eight starts, a stretch during which he went 0-4 with a 5.61 ERA. Martin wanted to send him to Spokane for two starts to build his confidence, but new team president Dr. Bobby Brown overruled him.29 Instead, Martin kept Clyde on the bench for 10 days. When he made his next start on July 5, Clyde was pulled in the first inning after ceding a hit and three walks to the Yankees. “I can’t fault David Clyde for the way he pitched tonight because that would not be fair to him,” said Martin after the game. “I know the situation and I know what he needs. His confidence is down, and he is not helping us right now.”30

Clyde was hardly put in a position to succeed with Martin at the helm. In addition to being in the skipper’s doghouse, Clyde received no instruction from his pitching coach, Art Fowler, who had replaced Estrada. “Art Fowler’s job was to get drunk with Billy on the road,” recalled Shropshire. “He wouldn’t know a release point from a whooping crane.”31 Because the Rangers were surprisingly in playoff contention during the second half, Clyde’s usage became sporadic, alternating between long relief and spot starts. Off the field, Clyde spent freely and partied excessively in an attempt to fit in with his older teammates. “What a time I had,” he said in 1981. “I’d go to Lord and Taylor’s in Chicago and buy a double-breasted suit and never ask what it cost. I’d take $500 and go to Aqueduct in New York and come back with just enough for a cab.”32 He finished the season 3-9 with a 4.38 ERA in 28 games (21 starts).

Clyde went directly to the Florida Instructional League at the end of the 1974 season to work on his off-speed pitches under the guidance of Rangers minor-league pitching coach Sid Hudson. Clyde then toiled for Águilas del Zulia, a Maracaibo-based club in the Venezuelan winter league, where he won only one of his five decisions while posting a 5.50 ERA.33 After filing for divorce from Cheryl that winter, he required a tonsillectomy as he was set to depart for spring training in Florida. Clyde lost 21 pounds while recuperating and reported to camp three weeks late, a delay which sealed his demotion to the minor leagues for the first time in his career.34 By then, he had time to reflect on his whirlwind two seasons in the big leagues. “Looking back, it may have been better if I had gone right into the minors after school,” said Clyde at the time. “That’s where pitchers are made, where you get the instruction and the teaching.”35

Clyde spent the majority of the 1975 season with the Pittsfield (Massachusetts) Rangers in the Double-A Eastern League. He enjoyed the relative obscurity of the minors and being able to work on his control and off-speed pitches without the winning pressure of the big leagues.36 In 22 starts, he compiled a 12-8 record, 3.07 ERA, 131 strikeouts, and 94 walks in 161 innings. When major-league rosters expanded in September, Clyde was recalled to Texas. By then, Martin had been replaced by Frank Lucchesi. Clyde pitched well in his only appearance, a start versus California on September 17 in which he took a three-hit shutout into the eighth before his own throwing error contributed to three runs and a Rangers defeat.

During the abbreviated 1976 spring training that resulted from an owners’ lockout, Clyde developed a shoulder problem. The issue cropped up after he had a shortened warmup while replacing Steve Barr, who had been struck on the leg by a line drive. “Two days later I went out to throw batting practice and I couldn’t pick my arm up,” Clyde later explained. “I threw anyway. I thought it was just tight.”37 The problem was a pinched nerve near the left shoulder blade for which Clyde received a cortisone injection and was prescribed 2½ weeks of rest.38 He returned to the mound with the Triple-A Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League but the zip on his fastball had vanished. He got off to an abysmal start, losing all four decisions while registering an 8.67 ERA in five starts before being shut down again. After seeking multiple opinions, the 21-year-old southpaw underwent surgery with Dr. Frank Jobe in Los Angeles and missed the remainder of the season. Jobe told him the chances of ever throwing again were 50-50.39

Clyde was left unprotected in the expansion draft in the fall of 1976, but neither the Mariners nor the Blue Jays took a flier. He showed up to Rangers’ spring camp in 1977 throwing without pain but had not regained his previous velocity.40 He was assigned to the Triple-A Tucson Toros—the Rangers’ new affiliate in the PCL—to start the season. Clyde struggled with his command, resulting in a move to the bullpen as the season wore on. In 34 games (21 starts), he went 5-7 and posted a 5.84 ERA. In 128 innings, he walked 119 and struck out 90. When Tucson’s season ended, he got in additional work in the Florida Instructional League. He also returned to Venezuela, going 1-2, 8.20 in five games (four starts) for Tiburones de La Guaira.

On February 28, 1978, Clyde’s tenure with the Rangers came to an end when he was traded, along with Willie Horton, to the Cleveland Indians for Tom Buskey and John Lowenstein. Clyde’s new manager (Jeff Torborg) and pitching coach (Harvey Haddix) quickly saw that the young lefty still had plenty of life in his arm, but his mechanics were out of whack. They encouraged him to return to a full windup and abandon his slider. “I got more instruction here the first day than I got in five years with Texas,” said Clyde at the time.41

Clyde broke camp with the Indians as a long reliever and did not appear until Cleveland’s 18th game, throwing 4⅓ scoreless frames versus Oakland on April 29. He made his first start of the season on May 16 versus the A’s, a complete game gem in which he allowed two runs on four hits. He racked up seven strikeouts, including three in the first inning on 11 pitches, while issuing one walk and one hit by pitch.42 The solid showing earned Clyde a spot in Cleveland’s starting rotation. He had mixed results, finishing the season with a pedestrian 8-11 record and 4.28 ERA. In a career-high 153⅓ innings pitched, he struck out 83 and walked 60.

Things got off to a rocky start for Clyde in 1979. He was treated for gastritis during spring training and struggled on the mound, allowing 12 runs to the Mariners in one contest and issuing nine walks to the Padres in another.43 He was ultimately diagnosed with a stomach ulcer and began the season on the 21-day disabled list. Clyde felt well enough to return in mid-May, but Cleveland had no room on its roster and kept him sidelined.44 He was finally activated on June 1 after his agent, Dick Moss, threatened to file a complaint with the Major League Players Association.45 Clyde pitched one inning in mop-up duty on June 15 and did not appear again until joining the Indians’ starting rotation on June 30.

His best performance of the season was a complete game win versus the Royals on July 9. Watching from the opposing dugout, Herzog observed that Clyde was throwing as hard as he did as a rookie.46 Clyde displayed improved control, as evidenced by a career-best 2.6 walks per nine innings, but he failed to find consistency, allowing five runs or more in four of his eight starts. “He was the same pitcher in 1979 that he was in Texas, not much of a breaking ball, not much of a changeup,” recalled Cleveland teammate Toby Harrah years later. “He hadn’t progressed much at all as a pitcher.”47 A back condition put Clyde out of action in August, and he would not appear again for Cleveland. His season ended with a 3-4 record and 5.91 ERA. On top of his physical maladies and poor pitching, Clyde divorced his second wife, Patty.

On January 4, 1980, the Indians traded Clyde—along with Jim Norris—back to the Rangers for Gary Gray, Larry McCall, and minor-leaguer Mike Bucci. Clyde spent the winter working out in Houston and went to spring training poised for a homecoming. However, he was beset by tendinitis in his throwing shoulder during camp, and Texas released him on March 31.48 After his shoulder failed to improve with rest, Clyde underwent surgery on May 7.49 He was forced to pay for the operation out of pocket and subsequently filed a grievance against the Rangers for cutting him while injured. “The head of the union advised me at the time that it’s a roll of the dice—a very gray area,” recalled Clyde. “I was presented with the opportunity to settle for 50 cents on the dollar or roll the dice.” With more than $30,000 in medical bills to pay, Clyde decided to settle rather than risk going to arbitration and getting nothing.50 While recovering, he spent nine months working sales jobs and driving a beer truck in Houston with hopes of making a comeback the following season.51

In April 1981, Clyde impressed enough during a 20-minute tryout at the Astrodome to ink a contract with his hometown Houston Astros—five days before his 26th birthday. Clyde was assigned to the Columbus (Georgia) Astros of the Double-A Southern League, where he posted his best numbers in professional baseball. By then, his fastball velocity had dipped to the 87-88 range, but he still found success.52 In 10 appearances (seven starts), he won all six of his decisions and recorded a 0.76 ERA, thereby earning a promotion to Triple-A Tucson, which had become an Astros affiliate. Clyde failed to replicate—or even approximate—his Double-A success in Tucson. In 19 starts, he compiled a 4-10 record and 6.85 ERA while walking more batters than he struck out.

Clyde announced his retirement from baseball in February 1982. “I decided I just didn’t want to do baseball anymore,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1986. “I was about to get married again, and I was missing a kid growing up. I retired, though I think I could have made it back to the majors.” When Clyde stepped away from baseball, he was 37 days away from four years of service time—the threshold required at the time to qualify for Major League Baseball’s pension plan and health insurance benefits. It was not until 2011 that MLB agreed to provide an annual stipend—paid for by the league’s competitive balance tax—to players whose career ended before 1980 and fell short of the four-year mark. Clyde, who last pitched in the majors in 1979, receives an annual benefit of $8,750 per year (before taxes).53

Following his nine years in the limelight of professional baseball, Clyde went to work with his father-in-law at McCauley Lumber Company in Tomball, Texas, a small town 40 miles outside of Houston. He also coached youth baseball in his spare time. In addition to a son (Ryan) from his second marriage, Clyde had two children (Reed and Lauren) from his third marriage to the former Robin McCauley, a union which ultimately ended in divorce. As of 2023, Clyde was retired but still coaching young pitchers, and still lived in Texas.

Clyde’s career arc serves as a cautionary tale for what can happen when a young player is rushed to the big leagues. “It was the dumbest thing you could ever do to a high school pitcher,” said Tom Grieve, Clyde’s teammate and later the Rangers’ GM. “In my opinion, it ruined his career.”54 Clyde has been interviewed countless times in the decades since his career flamed out and has consistently expressed no bitterness or regret. “Baseball brought me a lot of heartaches,” said Clyde 20 years after his memorable debut, “but it made me a better person.”55

Last revised: January 17, 2023

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to David Clyde for sharing his personal memories and clarifying facts in a January 2023 telephone interview.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com and Pelotabinaria.com.ve (Venezuelan winter league stats).

Notes

1 Gene Wojciechowski, “From Baseball to Tomball,” Los Angeles Times, September 9, 1986: 27.

2 Clyde is one of four players to jump from high school to the major leagues since the amateur draft was instituted in 1965. The others are Mike Morgan, Tim Conroy, and Brian Milner, all of whom debuted in 1978.

3 Telephone interview between David Clyde and the author, January 3, 2023.

4 Jeff Merron, “The Rise…and Fall of a Phenom,” ESPN.com, May 30, 2003, http://a.espncdn.com/mlb/s/2003/0529/1560431.html, accessed December 22, 2022.

5 David Fuller, “Legion Tournament Starts Here Wednesday,” Longview News-Journal, August 8, 1971: 10.

6 Buck Francis, “Westchester Ace Great,” Corpus Christi Times, June 5, 1972: 14.

7 Bill Hunt, “Things Did Get Worse,” Corpus Christi Times, June 11, 1972: 39.

8 One of the two hits he allowed was a home run off the bat of David Bialas, who would go on to a 10-year minor-league career in the St. Louis Cardinals organization.

9 Harold McKinney, “Clyde Could Solve Two Ranger Problems,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 10, 1973: 39.

10 Bob Clanton, “Football, Curls Out for Clyde,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 14, 1973: 58.

11 From 1953-57, players signed for a bonus of $4,000 or more were required to be on the 25-man major league roster for two years.

12 Brad Townsend, “David Clyde: Franchise Savior and Cautionary Tale,” Longview News-Journal, June 30, 2013: D4.

13 Merron, “The Rise…and Fall of a Phenom.”

14 Whitey Herzog and Jonathan Pitts, You’re Missin’ a Great Game (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999), 169.

15 Galyn Wilkins, “Slow Crowd, Fast Arms Clyde’s Big Night,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 29, 1973: 27.

16 Gary Long, “Orioles ‘Big Guys’ Give Clyde Trouble,” Miami Herald, March 15, 1974: 291.

17 Mike Shropshire, Seasons in Hell, (New York, Penguin Group: 1996), 67.

18 Shropshire, Seasons in Hell, 69.

19 Whitey Herzog and Kevin Horrigan, White Rat: A Life in Baseball (New York: Harper and Row, 1987), 90.

20 Clif Keane, “Sox Best Crafty Clyde,” Boston Globe, July 13, 1973: 53.

21 “Experts Say Young Stars Need Minor Experience,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 8, 1973: 42.

22 Peter Gammons, “Hopefully, This Baby’s a Feller, and Not a Krausse,” Boston Globe, July 13, 1973: 53.

23 Whitey Herzog and Kevin Horrigan, White Rat: A Life in Baseball (New York: Harper and Row, 1987), 91.

24 Mike Shropshire, “Birds Soaring High on Doomsday Defense,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 28, 1973: 18.

25 Fred Rothenberg, “Billy Martin Praises Youthful David Clyde,” Bridgeport Post, September 22, 1973: 10.

26 Dave Distel, “Rangers’ Babe of Summer Grows Up in Big Leagues,” Los Angeles Times, September 27, 1973: 19.

27 Townsend, “David Clyde: Franchise Savior and Cautionary Tale.”

28 Bruce Weber, “Brad Corbett, Who Owned Texas Rangers, Dies at 75,” New York Times, December 27, 2012: 25.

29 Mike Shropshire, “Shelled Rangers Regroup,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 6, 1974: 9.

30 “David Clyde Issue Irks Billy Martin,” South Bend News, July 7, 1974: 69.

31 Merron, “The Rise…and Fall of a Phenom.”

32 Ira Berkow. “Clyde, at 26, Starts 2d Comeback Bid,” New York Times, May 5m 1981: B15.

33 “David Clyde’s Future Very Much in Question,” Naples Daily News, March 14, 1975: 60.

34 “David Clyde’s Future Very Much in Question.”

35 Jim Sarni, “Texas’ Clyde Faces a Minor Problem,” Fort Lauderdale News, March 26, 1975: 53.

36 “Clyde Fond of New Obscurity,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 22, 1975: 31.

37 Bob Nold, “Confidence Important for ‘Reborn’ Clyde,” Akron Beacon Journal, March 27, 1978: 24.

38 Nold, “Confidence Important for ‘Reborn’ Clyde.”

39 Nold, “Confidence Important for ‘Reborn’ Clyde.”

40 Jim Reeves, “Clyde on Mend, But Impressive,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 2, 1977: 37.

41 Nold, “Confidence Important for ‘Reborn’ Clyde.”

42 Bob Nold, “Tribe Faith in Clyde Rewarded,” Akron Beacon Journal, May 17, 1978: 45.

43 Bob Nold, “Clyde Takes Another Step Backward,” Akron Beacon Journal, March 27, 1979: 39.

44 Bob Nold, “Price Tag on Jones is Too High for Indians,” Akron Beacon Journal, May 26, 1979: 10.

45 Hank Kozloski, “Clyde ‘Hurts’ for Wayne Cage,” News Journal (Mansfield, OH), June 2, 1979: 14.

46 “4 Cleveland Players Hit Homers to Back David Clyde’s 5-Hitter,” Lima (Ohio) News, July 10, 1979: 16.

47 Merron, “The Rise…and Fall of a Phenom.”

48 Paul Domowitch, “Things Not So Bonny for Rangers’ Clyde,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 25, 1980: 30.

49 Michael A. Lutz, “David Clyde … Was He Treated Fairly?” Wichita Falls Times, May 8, 1980: 26.

50 Clyde telephone interview.

51 Mike Lane, “The Lonely Ranger,” Columbian (Vancouver, WA), July 15, 1981: 28.

52 Marshall Klein, “Clyde Looks Bonnie on the Comeback Trail,” Los Angeles Times, July 3, 1981: 36.

53 Levi Weaver, “David Clyde Kept Baseball in Arlington—and missed an MLB Pension by 37 Days. Does the Sport Owe Him Anything,” January 31, 2019, https://theathletic.com/766944/2019/01/31/david-clyde-kept-baseball-in-arlington-and-missed-an-mlb-pension-by-37-days-does-the-sport-owe-him-anything/, accessed December 23, 2022.

54 Townsend, “David Clyde: Franchise Savior and Cautionary Tale.”

55 Jennifer Briggs, “Too Much Too Soon?” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 13, 1993: 53.

Full Name

David Eugene Clyde

Born

April 22, 1955 at Kansas City, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.