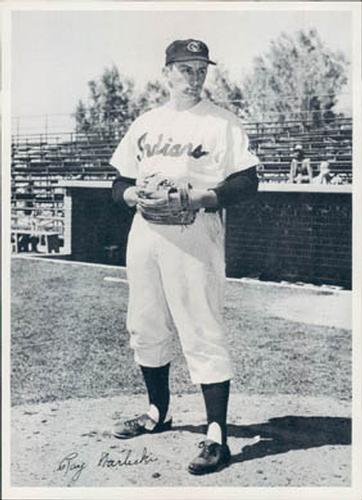

Ray Narleski

The hot days of summer strolled lazily by Cleveland in 1954. The Indians were looking to sweep the visiting Chicago White Sox on the July Fourth holiday and make it four straight victories over the Pale Hose and seven straight overall. Cleveland was flexing its muscles, in first place with a 4½-game lead over the New York Yankees in the American League standings, and showing no signs of letting up.

The hot days of summer strolled lazily by Cleveland in 1954. The Indians were looking to sweep the visiting Chicago White Sox on the July Fourth holiday and make it four straight victories over the Pale Hose and seven straight overall. Cleveland was flexing its muscles, in first place with a 4½-game lead over the New York Yankees in the American League standings, and showing no signs of letting up.

Besides its stellar pitching rotation, Cleveland’s success could be credited to two unheralded rookies in the bullpen. The pair of relief specialists offered manager Al Lopez the luxury of bringing in either Don Mossi, a left-hander with a sweeping delivery and a big curve, or Ray Narleski, a right-hander who presented a contrast to Mossi‘s style by throwing inside with heat.

Narleski got to the ballpark early this Sunday, arriving in the morning at the urging of bullpen coach Bill Lobe. “Funny thing about it, he was so wild I was afraid to stand up to the plate,” said Lobe. “The day before I told him he might be getting rusty and we decided to come out early.”[fn]Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 5, 1954.[/fn] Narleski took to the outfield to shag fly balls. He was not anticipating any early work, as Mike Garcia was the scheduled starter for Cleveland. The Bear could eat up innings, with 258⅔ pitched by the end of this season.

But after Garcia retired the first four batters he faced, a blood vessel ruptured on the middle finger of his pitching hand and forced him out of the game in the second inning. Enter Narleski, who responded to the early SOS from Lopez by tossing 5⅔ innings of no-hit ball and earning his second victory of the season. He struck out five and gave up just one run, on a walk, a wild pitch, a groundout, and a throwing error in the eighth inning when, by his own admission, he was tiring. “After I walked Sherman Lollar to start the inning, I just didn’t know where the ball was going,” Narleski said after the game.[fn]Ibid.[/fn] Early Wynn, in one of only four relief appearances that season, worked the final two innings, giving up the only White Sox hit, a single by Minnie Minoso with two outs in the ninth inning, and preserving the 2-1 victory for Narleski.

Ray Narleski performed at a high level for five seasons in Cleveland. Eventually, arm trouble curtailed his career, but his ability to pitch fast and with precision to the batter made him a feared competitor.

Raymond Edmond Narleski was born on November 25, 1928, in Camden, New Jersey. He was one of five children born to William E. and Marie Narleski. Bill Narleski, known as Cap, was a utility infielder for the Boston Red Sox in 1929 and 1930, had a long minor-league career, and played on many semipro teams when Ray was growing up. The family moved many times in southern New Jersey, and spent some time in Chester, Pennsylvania, not far from New Jersey. Ray’s younger brother Ted was a star offensive back for UCLA in the early 1950s. Later he played in the Indians farm system for three seasons.

Ray starred in baseball and football at Collingswood (New Jersey) High School. However, because of the family’s many moves, he turned 19 years old before the start of his senior season, and was ineligible to play. Many of the scouts who were following Narleski believed he was not playing because of injury, and their interest waned. However, Indians scout Billy Whitman knew the real reason why Ray was idle and signed him after graduation. Part of the deal was that Bill Narleski would be taken on as a scout. There was also a verbal agreement that Narleski would be given a pact with Triple-A money after one year of playing Class A ball. Narleski also found the time to get married before he embarked on his pro career, exchanging “I do’s” with his high-school sweetheart, Ruth May Gilbert.

Narleski started his pro career at Wilkes-Barre of the Eastern League, where his 2-10 record prompted manager Bill Norman to feel that he may have been over his head in Class A. But Norman saw potential in the young pitcher. “He showed a lot of promise because he could really hum that seed,” Norman later recalled.[fn]The Sporting News, March 11, 1959, 16.[/fn] But the Indians didn’t keep their end of the verbal agreement, and Narleski decided to sit out the 1949 season. He soon found out that Cleveland general manager Hank Greenberg, who had been unaware of the promise made to Narleski, could be just as stubborn. To keep in shape, Narleski played semipro ball while working at the RTC Shipbuilding Company.

Bill Norman, still managing at Wilkes-Barre, counseled Narleski and eventually persuaded him to return to baseball. Narleski got a slight pay raise, and restarted his career in 1950 at Cedar Rapids of the Class B Three I (Illinois-Indiana-Iowa) League. His record improved there, and in 1951 at Dallas in the Texas League. In 1952 the Indians moved him up to Triple-A Indianapolis and after going 11-15 that season, he flourished in 1953 under manager Birdie Tebbetts. The veteran catcher noted that Narleski would sail through the opposition’s lineup for two or three innings, and then get shelled. Figuring that Narleski could flourish as a reliever, Tebbetts asked Greenberg to approve the switch. Greenberg, recalling the contract squabble with Narleski, told Tebbets, “I don’t care what you do with him.”[fn]Tebbetts, Birdie, and James Morrison. Birdie: Confessions of a Baseball Nomad., Chicago: Triumph Books, 2002, 130-131.[/fn] Narleski also balked at the idea, fearing his salary would be cut because he wouldn’t pitch as many innings. Assured that Greenberg had no intention of reducing his pay, Narleski agreed to Tebbetts’ plan. “I accepted it because I had to, but I didn’t get paid for it, and that’s the part I didn’t appreciate,” Narleski said years later. “I always felt I was underpaid.”[fn]Schneider, Russell. Whatever Happened to “Super Joe”? Chicago: Gray & Company, 143-147. [/fn]

Narleski, now 25, made the Indians roster out of spring training in 1954, and he and Mossi anchored a superior bullpen. Though the common intelligence is that a team can never have enough pitching, Cleveland had almost too much. The Big Four of the starting rotation were Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, Mike Garcia, and Bob Feller. Lemon and Wynn led the American League with 23 wins apiece, while Garcia was the ERA king at 2.64. Add to the mix 13 wins for an aging Feller and 15 for Art Houtteman, the rotation was indeed formidable. Besides Narleski (3-3, 2.22 ERA, 13 saves) and Mossi, the Indians also signed veteran Hal Newhouser to shore up the bullpen.

A game against the Yankees at Yankee Stadium on June 2 typified the strength of the bullpen. Wynn started but was taken out in the first inning by manager Al Lopez after giving up four runs without getting an out. His replacement, Mossi, surrendered three more runs in the first inning, putting the Indians in a 7-0 hole after one inning. But a parade out of the bullpen, including Narleski, Bob Hooper, Garcia, and finally Newhouser, no-hit New York the rest of the way. Cleveland climbed back in the game and tied the score on a home run by Bobby Avila in the ninth inning, then winning, 8-7, when Al Smith homered in the tenth.

“Narleski’s fastball takes off,” said catcher Jim Hegan. “He throws it around the letters and it usually moves in on a right-handed batter and away from a left-hander. When he gets it high enough, it’s almost impossible to hit.”[fn]Baseball Digest, October 1955, 73-86.[/fn]

On offense the Indians were led by Avila, Larry Doby, and Al Rosen. They won 111 games, an American League record that stood until 1998, and finished ahead of New York by eight games.

Cleveland was heavily favored to beat the New York Giants in the World Series, which began at the Polo Grounds in New York. A superstitious fan might have been alarmed when the team, amid a throng of well-wishers, departed from the train terminal on Track 13. Superstition may have been as good a reason as any to explain how the Indians were swept in four games. The Series began on a Wednesday and was over by Saturday. It was a complete collapse. The Indians hit .190 and their pitchers posted a 4.84 earned-run average. Giants bench player Dusty Rhodes contributed three timely hits, including two home runs, and Willie Mays’s catch off Cleveland’s Vic Wertz in Game One has gone down in baseball legend. Narleski pitched in Games Three and Four, giving up one run in four innings.

The save became an official statistic in 1969, when Narleski had been out of Organized Baseball for a decade. The criteria for which a pitcher is credited with a save has been amended a handful of times over the years. At first a pitcher got a save simply for finishing a winning game without getting credit for the victory. There was no requirement for the number of innings pitched or what the on-base situation was when the pitcher entered. Retroactively, Narleski has been given credit for 58 saves in his six major-league seasons, and if it were an official statistic in 1955 he would have led the American League with 19.

Narleski and Mossi became close friends and roomed together on the road. Their careers were bounded by honing their trade in the bullpen, side by side. Although both pitchers preferred to be in the starting rotation, relief work would be their calling for now. (From 1957 through 1959, the last season on the Detroit pitching staff, Narleski made 49 starts.) But in their early days, Cleveland manager Lopez made full use of the pair, never hesitating to pull a starter at the slightest hint of an oncoming predicament. “I know they’d do well if I started them every four days,” Lopez said in 1955, “but I hate to take them out of the bullpen. They’re more valuable there, at least right now since we have plenty of starters.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

It was almost impossible to see a story written about one player that did not include the other. Their success earned them many nicknames during their years in Cleveland. Among them, were the Toss Out Twins, the Gold Dust Twins, and the Tremendous Two. “Finding them was like finding gold dust,” said first baseman Vic Wertz. “Because of them we cashed in on pennant gold last year and if we do it again they’ll deserve the credit.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

Wertz’s words were almost prophetic. In 1955 Herb Score injected some youth and a blazing fastball into the rotation. Besides his 19 (unofficial) saves, Narleski had a 9-1 record. After sweeping a doubleheader from Washington on September 13, Cleveland held a two-game lead over New York in the standings. But the Tribe could not close the deal, losing six of nine down the stretch while the Yankees won nine of 11.

Hal Lebovitz, who covered the Indians for the Cleveland News, wrote, “They just ran out of gas, carrying an immense load of problems. The bullpen did a terrific job, but Narleski tired under the strain. (Outfielder Al) Smith had no chance to rest. A few key men had to carry the load – and they ran out of gas in the home stretch, that’s all. The other Indians let Smith and Narleski down by not taking up the slack. These two men carried the ball all season and their tremendous effort was wasted because their teammates couldn’t carry the burden the one time they had to.”[fn]The Sporting News, October 3, 1955, 8.[/fn]

Lebovitz had a point on Narleski’s tiring. Ray led the league in appearances with 60, while Mossi pitched in 57 games. Combined, they took the ball for just under 200 innings. Narleski finished sixth in the Most Valuable Player voting.

Narleski improved on those numbers early in the 1956 season. From May 25 to June 20, he did not surrender an earned run in 24⅔ innings pitched. But on July 2, he pulled a muscle in his right elbow and missed two months. He had been selected to participate in the All-Star Game, but was forced to sit it out. He returned in early September and wound up the season with a sparkling ERA of 1.52 in 32 games.

Lopez left the Indians after the season to take the reins of the Chicago White Sox. In his six seasons at the helm in Cleveland, the Tribe had never finished lower second place. Greenberg promoted Kerby Farrell from Triple-A Indianapolis to steer the ship. The change in managers was among factors that led to the Indians dropping to sixth place in 1957. The pitching staff suffered an unfortunate loss when Score was hit in the eye with a batted ball on May 7. Then Lemon had bone chips removed from his elbow, further thinning out the rotation.

Narleski pestered Farrell for a chance to start, and Farrell acquiesced. From July 21 through August 8 Narleski won four of six games started, with no losses. Mossi also got some starts, and he and Narleski combined for 37 starts. “He deserves to remain a starter,” Farrell said of Narleski. “He’s done a great job for us, really saved our lives. But taking him out of the bullpen hurts, too.”[fn]The Sporting News, August 14, 1957, 25.[/fn] Narleski ended the year with an 11-5 record and an ERA of 3.09. He also had 16 “saves.” In a relief appearance on June 23 in Washington, Narleski socked the first and only home run of his major-league career (He also hit one in the minors.) The Washington blast, a three-run shot off the Senators’ Russ Kemmerer in the eighth inning, provided the winning margin in a 7-5 victory.

Kerby Farrell was replaced after one year by Bobby Bragan. Bragan had previously managed in Pittsburgh, to no great avail. He was the choice of the new general manager, Frank Lane. Lane had replaced Greenberg, who rejoined Lopez two years later in Chicago.

Lane, known for the multiplicity of his trades, got to work right away. He sent Wynn and Smith to Chicago, and Hegan to Detroit. Lane was just warming up. If anything, he was impetuous, showing Bragan the door after 67 games. Former Yankees and Indians great Joe Gordon assumed control. Or as much control as a manager had under Lane.

The Indians were said to be pursuing a second baseman, and it was reported that they had their eye on New York’s Bobby Richardson. The New York World-Telegram and Sun reported that a trade involving Narleski and Richardson was a done deal. An agreement was never reached, which illustrated that even swaps that Lane didn’t make made headlines.

In 1958 Narleski was thrown into the revamped pitching rotation with Cal McLish, Gary Bell, and Mudcat Grant. He recorded a 13-10 mark, pitching in 183⅓ innings. He was named to the AL All-Star team, and pitched one-hit ball in 3⅓ innings. A muscle popped in his forearm as he threw a curveball. He had a hard time strengthening the arm unless he soaked it in the whirlpool.

After the All-Star break Narleski was returned to his familiar role as a reliever. “Frank [Lane] moved me back to the bullpen to knock me out of being a 20-game winner,” he said. “I didn’t want to go back to the bullpen. I was a starter and then refused to sign a 1959 contract with the Cleveland club.”[fn]National Baseball Hall of Fame Archives.[/fn]

In the offseason, the Indians were still trying to find a way to fill their need at second base. On November 20 Narleski, Mossi, and infielder Ossie Alvarez were traded to Detroit for second baseman Billy Martin and pitcher Al Cicotte. Narleski was thrilled with the move, as he always felt he was not being used correctly in Cleveland. Lane commented that Narleski and Mossi won just five games between them after Joe Gordon’s arrival, and just did not figure in the team’s plans. Detroit general manager John McHale said he hated to give up Martin, “but we feel Narleski and Mossi will win more games for us than Billy did.”[fn]Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 21, 1958.[/fn]

Joining the Tigers, Narleski was reunited with Bill Norman, his minor-league skipper who was now the head man in the Motor City. “We know that one of our big problems last year was in bullpen help,” Norman said. “When one of our starters weakened, we were in trouble. With Narleski and Mossi to come in and bail us out, I think we will be a lot better off.”[fn]The Sporting News, January 21, 1959, 3.[/fn]

But for Norman, Narleski, and the Tigers, the 1959 season did not unfold as they might have hoped. The Tigers wobbled out of the gate with a 2-15 record and Norman was fired. Narleski had been nursing a bad back since spring training, and his performance on the mound reflected the pain he felt. He posted a 4-12 record with a 5.78 ERA. His back never did heal properly. After surgery in 1960 to repair a disk, he was hospitalized for six weeks. He was on the disabled list for the entire 1960 season. In 1961, Detroit planned to send him to Triple-A Denver. Narleski refused the reassignment, and was released on March 31, 1961. After six seasons and more than 700 innings pitched, he finished his career with a record of 43-33 and an ERA of 3.60. He also totaled 58 unofficial saves.

In retirement Narleski played semipro ball in New Jersey and Delaware. He went to work as a mechanic/truck builder for H.A. DeHart Trucks in Thorofare, New Jersey. He and Ruth had three sons, Ray Jr., Steven, and Jeffrey. Steve Narleski signed with the Indians and spent a few years in their minor-league chain.

Narleski lived out his retirement years in Camden, New Jersey. “What the hell, I had a great career,” he told a writer in 2006. “OK, I am bitter about a couple of things … and it’s not just that they kept me in relief. If they had just paid me what I was worth, I would not have been pissed off about not starting, although I know I could have been successful and made a lot more money. If that’s having an attitude, so be it, I had one.”[fn]Schneider, Whatever Happened to “Super Joe”? 147.[/fn]

Ray Narleski passed away from natural causes on March 29, 2012.

This biography is included in the book Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press,click here.

Full Name

Raymond Edmond Narleski

Born

November 25, 1928 at Camden, NJ (USA)

Died

March 29, 2012 at Clementon, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.