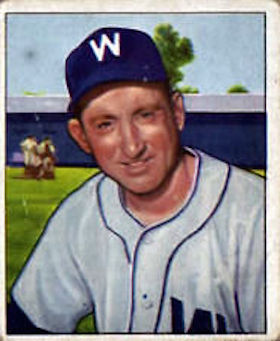

Ray Scarborough

Right-hander Ray Scarborough pitched for the Senators, White Sox, Red Sox, Yankees, and Tigers during his 10 years in the major leagues. His longest stretch was with the Washington Senators, pitching in seven of those seasons, from 1942 into 1950. He was 80-85 for his career, with a lifetime 4.13 earned run average.

Right-hander Ray Scarborough pitched for the Senators, White Sox, Red Sox, Yankees, and Tigers during his 10 years in the major leagues. His longest stretch was with the Washington Senators, pitching in seven of those seasons, from 1942 into 1950. He was 80-85 for his career, with a lifetime 4.13 earned run average.

Scarborough’s best season was 1948, when he compiled a 15-8 record (with a 2.82 ERA) working for manager Joe Kuhel and the seventh-place 56-97 Senators. No other pitcher on the team won more than eight. Both stats cited for Scarborough were personal career highs.

Rae Wilson Scarborough was born at Mount Gilead, North Carolina, on July 23, 1917, the son of Bina Scarborough and her husband, Oscar, a former mail carrier, then a farmer, who was a general store operator and cotton broker. Until the 1930s, cotton farming was the biggest cash crop right in the area about 55-60 miles due east of Charlotte and about 90 miles south and a little west from Greensboro. Of Scottish-Irish descent, Rae was the fourth of seven children in the family; Oscar Scarborough, who had been a lefty pitcher for local semipro teams, built a baseball field for his kids. By 1949, when Ray was in the big leagues and building a home for himself, he told reporters that his father had a hardware store.1

Rae attended the public schools in Mount Gilead, then Rutherford Junior College, and graduated from Wake Forest with a B.S. in 1942. He also played basketball, football, and tennis in college. He was Phi Beta Kappa, and began work as a biology and science teacher. That was his intended career, before baseball took precedence.2 For the Wake Forest Deacons, he pitched 33 innings and struck out 50 batters for Coach John Caddell. He won five games.3

Scarborough played American Legion ball at Troy, North Carolina, and semipro baseball in several North Carolina communities – Aberdeen, Hickory, Rutherford, and Roanoke Rapids.4

He was recommended by Zinn Beck and signed by Joe Engel for the Washington Senators out of Wake Forest.5 He was signed to the Class-A1 Chattanooga Lookouts in the Southern Association (independent at the time but soon taken over by Washington).That cost Scarborough financially. Engel gave him a $2,000 bonus and had promised him half the sale price if the Lookouts sold his contract to a major-league team. As it happened, Al Hirshberg explained, “In 1941, Engle couldn’t afford to keep the Lookouts. The club reverted back to the Washington Senators, from whom Engel had bought it. Scarborough, without collecting a cent, automatically became the property of the Senators.”6 Scarborough started seven games for manager Kiki Cuyler, in the remainder of the 1940 season, and appeared in five others. His record was 1-3 with a 5.54 ERA.

On October 30, 1940, he married Edna Martin, a home economics teacher from Tabor City, North Carolina. They later had two children, Beverly (Scarborough) Blackwelder and Shirley (Scarborough) Johnson.

In 1941, Scarborough became a 20-game winner. He was dropped down to Class B and pitched in Alabama for the Southeastern League’s Selma Cloverleafs. His 220 strikeouts led the league, as did his 21 wins (he was 21-10, with a 3.17 ERA.) The previous league record for strikeouts had been 205; in the same game, against Meridian, Scarborough broke the record and won his 20th game. In 1942 he joined the Senators at the start of spring training at Orlando but in early April was assigned to Chattanooga again; he worked in 15 games (13 of them as a starter) and was 8-5, 4.55.

Scarborough’s major-league debut came on June 26, 1942. He had in fact begun work as a biology teacher, and the Washington Evening Star welcomed his call-up referring to him as a “former high school biology teacher.”7 The paper called him a “small, wiry, right-hander with a sizzling fastball [who] has been pitching creditably for Chattanooga.” Scarborough actually was an even six feet tall and listed at 185 pounds. The same day’s Washington Post called him a “scholarly curveballer.”8 He also threw a knuckleball.

His debut came in St. Louis, relieving in a game started by Bobo Newsom. It was 7-3, Browns, after six innings. Scarborough pitched the seventh for skipper Bucky Harris. He gave up one run on two hits, the one run coming on a solo home run by Chet Laabs. The very next day, he pitched again, this time working two innings of relief in a game the Browns led, 7-0. Scarborough gave up one more run, with two hits and two bases on balls. In the second game of the June 28 doubleheader – still in St. Louis – he worked one more inning. The Senators had won the first game, and had a two-run lead in the second game after seven innings. Scarborough retired the side in the eighth but walked the first batter of the ninth, and went to 2-0 on the next, when Harris called in Alex Carrasquel. The inherited runner scored, but the Senators held on to win, 7-6.

He relieved four more times in July, the best time being four innings against the visiting Browns on June 19, in which he was charged with only one unearned run. Nonetheless, and despite a 4.76 ERA, he’d given up one or more runs in each of his first six appearances. On July 31, in Chicago, he pitched 3 1/3 innings of one-hit scoreless relief. He worked five more games in August and brought his ERA down to 3.43.

Given his first starting assignment (against the White Sox, in the second game of a doubleheader at Washington’s Griffith Stadium on September 3), he shut out the White Sox, 14-0, on five hits. He walked four and struck out three. The Washington Post‘s Shirley Povich was succinct: “He pitched a beaut.”9

He won his next start, too, though while a win is a win, it’s a little difficult to enthuse about giving up nine runs (eight earned) in six innings. The Senators beat the Red Sox, but the score was 15-11, the game more a reflection on the poor pitching of the Red Sox staff.

At the end of the season, he was 2-1, having lost his final start, 4-1, to the Yankees. His first year in the majors saw him with an ERA of 4.12.

In 1943 he started six games but worked another 18 as a reliever. His record was 4-4 with three saves, and an impressive 2.83 ERA. He still walked more than he struck out, a problem that continued throughout his career. He was never much of a hitter, a career .186 batter with a .217 on-base percentage. In1948 he drove in nine runs, the best year of his career. One of them won a game, when Scarborough hit a 12th-inning single to win the game against the White Sox. As a fielder, he wasn’t among the best, with a .936 fielding percentage.

His last game in 1943 was on August 3, after which he reported for duty with the United States Navy. That’s when he learned, for the first time, that his first name was spelled the more typical way: Ray.10 He trained at St. Mary’s College in California, and found himself playing a fair amount of baseball for the St. Mary’s Pre-flight nine.

The years 1944 and 1945 were spent in the service. Lt. Scarborough rejoined the Washington Senators in early March 1946. The team, under Ossie Bluege, finished fourth with a 76-78 record. Scarborough was 7-11 with a 4.05 ERA (the team ERA was 3.74). He was the fourth starter on a team that had seven pitchers start a dozen or more games. Had he not lost every one of the six games he pitched in August, he would have had a much better record. The Senators only scored a total of nine runs in the six games. His final game of the year was a 7-0 shutout in Boston, which no doubt left him feeling a little better through the offseason.

In 1947 he pitched more effectively – his earned run average was 3.41, but his won/loss record was 6-13. This time, it more closely reflected the team’s 64-90 record, which saw the Senators in seventh place. Scarborough worked almost exclusively in relief until early July. There was an interesting incident in July when umpire Bill McGowan threw his balls-and-strikes indicator at Scarborough, “annoyed by Scarborough’s shaking his head after some of McGowan’s decisions.”11 McGowan was suspended.

Again there was a stretch in August and September when he incurred loss after loss. This time he lost eight consecutive decisions from August 16 through September 17. In seven of the eight losses, the Senators scored either just one run or no runs at all. In four of the games Washington was shut out, Scarborough gave up a total of seven runs. He won his last two starts, a shutout of the Red Sox and a 4-3 complete game win over the Philadelphia Athletics.

His 1948 season was excellent. Though without a shutout all year, he was 15-8 with a 2.82 ERA, second-best in the league. Only Cleveland’s Gene Bearden (2.43) had a better ERA. Scarborough was by far the best pitcher on Joe Kuhel’s 57-97 team. No other pitcher won more than eight games. “My luck has turned,” he said.12 He had spent the winter of 1947 constructing a home in Mount Olive, North Carolina. After the 1948 season he toured for a while with a team of “all-stars” assembled by Birdie Tebbetts.

Not surprisingly, it was reported that five teams had made offers to Washington to acquire Scarborough.13 One of the teams was the Boston Red Sox, whose slugger Ted Williams said Scarborough was “one pitcher I can’t hit…I can’t seem to hit that guy…I’d be better off if Ray never pitched against me.”14 Al Hirshberg later wrote, “Scarborough has been one reason why they [Red Sox] haven’t been able to raise a pennant on the flag pole at Fenway Park since 1946. He always happened to beat them when it hurt the most.”15

The Senators used him very much the same way in 1949, but he wound up with a 4.60 ERA and a 13-11 record, thanks to winning his final three decisions in September. His best game was a two-hit shutout of the Browns on June 15. He “curve-balled ’em into submission,” wrote Povich of the Post.16 Scarborough beat the Yankees twice and the Red Sox once in September, a season in which those two teams battled for first place until the final day. A Scarborough victory for two years in a row had arguably robbed the Red Sox of a pennant, with his 4-2 win on September 28, 1948, and his 2-1 win on September 28, 1949. Ted Williams later wrote of that final Red Sox loss, “It wasn’t the Yanks, it was Ray Scarborough… Scarborough was just one of those pitchers that baffled us.”17 The Senators finished in last place.

His five errors as a pitcher was worst in the league. As to the long ball, interestingly, he was not at all opposed to owner Clark Griffith‘s decision to move in the left- and center-field fences by 19 feet. “Sure, there’ll be more home runs, but it’s still a long wallop to that 386-foot fence and anyone who puts one in there deserves a homer. But I reckon it will help my own pitching record. It isn’t the home runs that scare me – it’s those nubbers, the Texas Leaguers that drop in front of the outfielders. With closer fences, they won’t be playing so deep.”18

Scarborough had initially been asked to take a $1,500 cut in pay for 1950 but, knowing he was a hot commodity in hot stove season trade rumors, he stuck to his guns and was granted a “slight increase” in salary.19 Tom Yawkey of Boston had reportedly offered $200,000 (or $150,000 plus players) for his contract over the wintertime, and in April it was said the Yankees had put together a package of five players for him.20 Nothing happened in April. He began the year with Washington, after a shaky spring (he surrendered 17 hits in one game and walked six in another), and he was a more or less mediocre 3-5 (4.01) by the end of May. Nonetheless, there was demand. The headline on Ed Rumill’s column in the Monitor expressed sentiments starkly: “Both Red Sox, Yankees Vie for Washington’s Ray Scarborough: Veteran Probably Could Win Pennant for Either.”21

There was a complaint by Clark Griffith that the Yankees’ Casey Stengel had essentially been tampering by openly “cooking up deals” that he discussed with sportswriters.22

The cum laude college graduate Scarborough was the head of the players’ grievance committee and player rep for the Senators, “and he was (and still is) an expert on the pension plan. Too many players make a mistake and use the offseason for relaxation. There comes a day when a player must make money somewhere else and how can he do that unless he’s prepared himself?”23

Finally, Scarborough was traded. Twice. On the final day of May (his father had died of a heart attack on May 22), Ray was part of a six-player trade with the Chicago White Sox, who received Al Kozar, Eddie Robinson, and Scarborough for Bob Kuzava, Cass Michaels, and Johnny Ostrowski. Scarborough had thought he might be traded to the Yankees or Red Sox, and Chicago came as a surprise. He admitted, “I was depressed, because I felt so deeply toward Mr. Griffith and I think Bucky Harris is the best manager in baseball.”24 There was considerable speculation at the time that the White Sox might be just a waystation, but the White Sox had a staff heavy with southpaws and needed a right-hander. Clark Griffith said the Senators had felt their weakest position was at second base and they hoped Michaels would help.25

Casey Stengel named him to the 1950 AL All-Star squad (though he did not appear in the game). But his time with the White Sox was sub-par, with a 5.30 earned run average and a record of 10-13. On December 10 came his second trade – from the White Sox to the Red Sox during the winter meetings. He and fellow pitcher Bill Wight went to Boston for Joe Dobson, Dick Littlefield, and Al Zarilla. Hy Hurwitz of the Boston Globe was not particularly impressed. He wrote, “His earned average of 4.93 is not impressive.”26 For Scarborough’s part, he thought it was “great news. It’s like jumping from the second division to the first division.”27

At least one writer, Furman Bisher, called him “the man who owes the Boston Red Sox a pennant, and hopes to pay the debt in 1951.”28

Scarborough was working in the offseason as a salesman for the Mount Olive Pickle Company, covering the Eastern cities north of Richmond. Boston was in his territory. The trade in pickles amused writers; Arthur Siegel of the Boston Traveler, for instance, dubbed him “the pitching pickle peddler.”29

Scarborough pitched one and a half seasons for the Red Sox – 1951 and the first half of 1952. Manager Steve O’Neill was hopeful that Wight and Scarborough, and Lou Boudreau would make the difference. As it happened, Scarborough’s ERA in 1951 was 5.09, almost a full run more than the team’s 4.14 ERA. He did have a 12-9 record. Only the 18-11 Mel Parnell won more games for the Red Sox. The team did not win the pennant, but finished third, 11 games behind the Yankees.

In 1952 new manager Lou Boudreau found Scarborough a disappointment in spring training.30 And he got off to a rough start; he was 1-4 by the end of May (despite a 3.57 ERA) and Boudreau only used him as a starter twice more all season. Indeed, the Red Sox put him on waivers and sold his contract to the Yankees on August 22. “He was no help to us,” said Boudreau. “I gave him plenty of chances to start and relieve and he didn’t come through.”31

In early September, the Red Sox said it was an “office error” that cost them Scarborough. They had optioned Ralph Brickner to Louisville, but the Commissioner’s office said that was illegal because there were fewer than 20 games left on Louisville’s schedule. Forced to take Brickner back, they had to dispense with someone else, so they put Scarborough on waivers.32

The difference in his records for the two teams produced mirror images in wins and losses. For the Red Sox, he was 1-5. For the Yankees, after their purchase, he was 5-1. (The one game he lost was in relief, after he loaded the bases in the bottom of the ninth in St. Louis on September 9 – and then hit Clint Courtney.) He had a 4.81 earned run average for Boston, and a 2.91 ERA for New York. The one win while with Boston was a 1-0 shutout of the White Sox on May 15; he allowed only four hits and one walk.

Did Scarborough have an explanation for such a reversal? He generously said he “never realized Yogi Berra was such a smart catcher.” 33

The day he won the first of his five games for the Yankees, on August 27, gained while pitching four innings of relief, the team was only two games ahead of second-place Cleveland and 3 ½ ahead of the third-place Red Sox. He won five of the team’s final 28 games, making a real contribution. Though the Red Sox plunged in the final standings, the Indians finished only two games back.

Scarborough was the team’s fifth starter and appeared only briefly in the 1952 World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers. He pitched in Game One at Ebbets Field, coming on in relief of Allie Reynolds. The score was 3-2 in favor of the Dodgers; manager Casey Stengel asked Scarborough to pitch the bottom of the eighth. He struck out pitcher Joe Black and induced groundouts by both Billy Cox and Duke Snider, who hit right back to the mound. But the third batter of the inning, just before Snider, was Pee Wee Reese, who homered into the lower left-field stands.

The Yankees lost the game, 4-2, but won the Series in seven games. Vic Raschi and Allie Reynolds each won two games. Scarborough was not called on to pitch again.

His last year in pro ball was 1953. He had worked in 25 games for the Yankees, all but one in relief, and was 2-2 with a good 3.29 ERA. He helped himself in one of the two wins, the one on May 29 against the Athletics, when he hit his only major-league home run, a three-run homer off Shibe Park‘s left-field façade in a 12-7 win, when he worked 8 1/3 innings of relief of Raschi. On July 31, the Yankees put both Scarborough and catcher Ralph Houk on waivers, while bringing up four minor leaguers. No one claimed Scarborough, so he was given his unconditional release on August 4. Eight days later, he signed with the Detroit Tigers.

For the Tigers, he appeared in 13 games, all in relief, and was 0-2 (8.27 ERA). When the season ended, so did his playing career. He announced his retirement on January 14, 1954.

After his retirement, he opened an “oil and supply company” in Mount Olive. He also “helped establish a baseball program at Mount Olive College.”34 In 1960 he took a position as a scout for the Baltimore Orioles. He managed for part of one season – 1961 – the third of three managers for the Leesburg Orioles in the Class-D Florida State League (one of the other managers was Cal Ripken Sr). He was a big-league coach for the Orioles in 1968. He later joined the California Angels in 1973. His last position was as a special assignment scout for the Milwaukee Brewers, beginning work for the Brewers in 1978.

He believed passionately in his work. Rory Costello wrote about the December 12, 1980, trade with the Cardinals, a trade that started as a smaller trade but eventually embraced seven players. Brewers scout Ray Poitevint argued against including David Green in the trade, a player the Cardinals’ Whitey Herzog really wanted. Former Brewers P.R. director Tom Skibosh recalled, “It got so heated that Ray Poitevint and Ray Scarborough almost came to fisticuffs in a meeting. Poitevint was saying, ‘David Green is the future of this organization,’ and Scarborough was saying, ‘Forget the future. We have a chance to get these guys; we want to win now.’ They almost went at it. They had to separate them.”35

Scarborough scouted until he died of a heart attack at home on the evening of July 1, 1982.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Scarborough’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com. Special thanks to Marty Tschetter, Wayne County Public Library, Goldsboro, North Carolina. With the consent of Ray Scarborough’s two daughters, the Wayne County Library has preserved digital images of the Scarborough family scrapbooks.

Notes

1 Burton Hawkins, “Win, Lose, or Draw,” Washington Evening Star, July 15, 1949: 16.

2 Ray Scarborough, American League questionnaire, in Scarborough’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 Scarborough Family Scrapbooks, Wayne County Public Library, undated newspaper clipping.

4 American League questionnaire. The Scarborough scrapbooks named the Roanoke Rapids Romancos and the Burlington Terrible Towers as among the semipro teams for which he pitched.

5 Kevin Kerrane, Dollar Sign on the Muscle (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books, 1999), 218.

6 Al Hirshberg, “Will Scarborough Make the Difference?” Sport, April 1951: 94.

7 “Nats Get Pitcher Scarborough Back,” Washington Evening Star, June 14, 1942: 36.

8 “Kennedy, Cathey Go to Lookouts; Scarborough Here,” Washington Post, June 14, 1942: C1. Pitchers Hardin Cathey and Bill Kennedy had been sent down to Chattanooga.

9 Shirley Povich, “Sid Hudson, Scarborough Win Games,” Washington Post, September 4, 1942: 14.

10 Al Hirshberg, 94.

11 Associated Press, “Senators’ Charges Bar Umpire McGowan,” New York Times, July 21, 1948.

12 “Fourth-Place Nats Saluting Ace Hurler Scarborough,” Washington Evening Star, June 8, 1948: 14.

13 “Nats Shun Latest Bid for Ray Scarborough,” Washington Evening Star, February 15, 1949: 16.

14 Francis Stann, “Win, Lose, or Draw,” Washington Evening Star, March 25, 1949: 52.

15 Al Hirshberg.

16 Shirley Povich, “Scarborough Gives 2 Hits, Griffs Routs Browns, 9-0,” Washington Post, June 16, 1949: 20.

17 Ted Williams, “Scarborough Beat Us, Didn’t Choke,” Boston Globe, September 2, 1962: 74.

18 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, March 1, 1950: 17.

19 “Scarborough Signs at ‘Slight Increase’,”Washington Evening Star, February 27, 1950: 15.

20 Dan Daniel, “Stengel Offers Five for Rae, Is Report,” New York World Telegram, April 22, 1950.

21 Ed Rumill, Both Red Sox, Yankees Vie for Washington’s Ray Scarborough: Veteran Probably Could Win Pennant for Either,” Christian Science Monitor, April 28, 1950: 8.

22 Daniel, “Griffith Threatens to Take Stengel Before Chandler for Scarborough ‘Talk’,” New York World Telegram, April 29, 1950.

23 Bob Addie, “Good Year, Then Why Slash?’ – Scarborough,” Washington Times-Herald, January 1950.

24 Francis Stann, “Win, Lose, or Draw,” Washington Evening Star, June 2, 1950: 50. Scarborough said, “I rate Clark Griffith the greatest club owner in the game. I know what he has to contend with, and he always has been fair to me.” Dan Daniel, “Talk of Big Trade Offers Rolls Off Ray,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1950: 3.

25 Associated Press, “Scarborough Goes to the White Sox,” New York Times, May 31, 1950: 41.

26 The quotation is accurate as presented. Hy Hurwitz, “Red Sox Obtain Pitchers Wight and Scarborough: Give Zarilla, Dobson, Littlefield in Trade With Chicago White Sox,” Boston Globe, December 11, 1950: 1.

27 Associated Press, “Scarborough Happy,” unidentified news clipping datelined December 20, 1951 found in Scarborough’s Hall of Fame player file.

28 Furman Bisher, “Scarborough Hopes to Pay Flag Debt to Bosox,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1951: 3.

29 Arthur Siegel, “Gamest Team Will Win – Doerr,” Boston Traveler, July 23, 1951: 23.

30 Larry Claflin, “Lou Miracle Man if Sox Win,” Boston American, April 4, 1952: 72.

31 Hy Hurwitz, “Sox Concentrate On Youth Movement, Others May Follow Scarborough Out,” Boston Globe, August 23, 1952: 4.

32 Clif Keane, “Sox Learn Sale of Scarborough ‘Office Error’,” Boston Globe, September 3, 1952: 6. They could have released Brickner, but clearly favored him over Scarborough.

33 Frank Keyes, “Grist from the Sports Mill,” Hartford Courant, September 30, 1952: 13.

34 Associated Press, “Ray Scarborough, 64, Major League Pitcher,” New York Times, July 3, 1982: 19.

35 Dennis Punzel, “Brewers’ Trade Dilemma Has Familiar Ring,” The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), July 6, 2008. See Rory Costello, “David Green,” http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/7f6a3dbf

Full Name

Ray Wilson Scarborough

Born

July 23, 1917 at Mount Gilead, NC (USA)

Died

July 1, 1982 at Mount Olive, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.