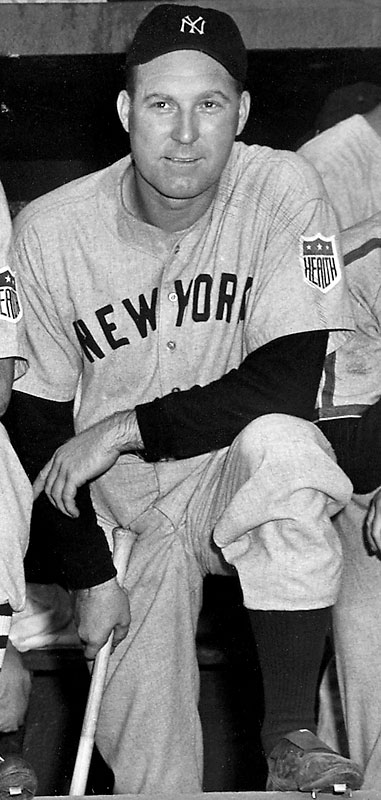

Red Ruffing

Hall of Famer Red Ruffing’s career is a reminder that you can’t judge a pitcher by his wins and losses. The right-hander lost more than 20 games twice while pitching for the last-place Red Sox and won at least 20 for four straight years with the World Series champion Yankees.

Charles Herbert Ruffing was born in Granville, Illinois, on May 3, 1905, one of five children of German immigrants John and Frances Ruffing. He spent his childhood in nearby Coalton, attending schools in Nokomis. The nickname “Red” came from his hair color, but his family called him Charley and his wife called him Charles. He signed some autographs “Chas. ‘Red’ Ruffing.”

Ruffing’s father was a coal miner until he broke his back. He took a job in the company office and rose to be the mine superintendent. He also served as mayor of Coalton. Charley quit school and went into the mine when he was 13, working for three dollars a day. It was punishing physical labor, 600 feet underground, often swinging a pick while stooped over. And it was dangerous; he saw a cousin killed in an accident. At 15 Charley was working as a coupler, hooking coal cars together, when his left foot was crushed between cars. Doctors managed to save the foot, but he lost four toes.

He had been a hard-hitting outfielder and pitcher for the company baseball team, managed by his father. While he was on crutches recuperating from his accident, Doc Bennett, a former minor leaguer who managed a local semipro team, encouraged him to concentrate on pitching, since he would no longer be able to run well. When Ruffing was 18, Bennett arranged his first professional contract, with Danville, Illinois, just 140 miles from home in the Class-B Three-I League. After one season in Danville, he was sold to the Boston Red Sox. The 19-year-old was hit hard in six appearances and went back to the minors in July 1924. When Boston recalled him in September, he was in the big leagues to stay.

Ruffing joined the Red Sox just as the club plunged into the bleakest period in its history. Boston finished last in each of his five full seasons, losing more than 100 games three times. Sportswriter Stanley Frank wrote that owner Bob Quinn “was operating the Red Sox on a frazzled shoestring.”1 Quinn’s predecessor, Harry Frazee, had traded or sold most of the team’s best players. Several, including that Ruth kid, went to the Yankees.

Although Ruffing was the Red Sox’ top pitcher, he showed no sign of greatness. Today he would be tagged with the backhanded compliment “inning eater.” Relying primarily on a whistling fastball, he posted a better-than-average ERA only once, and then just barely better. His 39 victories and 96 losses gave him a .289 winning percentage, even worse than his team’s sorry .344. After he batted .314 in 1928 while losing a league-leading 25 games, the Sox considered shifting him to the outfield but found that his mangled foot slowed him down too much.

Owner Quinn faced one of his frequent financial crises in May 1930. Red Sox scout Pat Monahan recalled, “He was real worried. He said he’d have to raise $67,000 in 48 hours to make a payment. ‘If I don’t make it, Pat, they’ll foreclose. I know they will.’” Quinn swapped the 25-year-old Ruffing to the Yankees for backup outfielder Cedric Durst plus $50,000 and, according to Monahan, an additional $50,000 loan from Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert.2 The trade rated only a one-inch story in the New York Times, describing Ruffing as “an in-and-outer.”3

The deal made Ruffing’s career. The turnaround in his fortunes began the first time he took the mound for New York, when Babe Ruth slammed a first-inning home run. Ruffing gave up six runs to the Tigers, but knocked in the deciding runs himself with a single and two RBIs. Late in the season he won six straight decisions. He sealed his place on the team with a two-hit shutout over the pennant-bound Philadelphia Athletics in September. He finished 1930 with a 15-5 record for the Yankees; his 4.14 ERA was better than average in the Year of the Hitter. He also batted a career-high .364 with four homers.

Bob Shawkey , a former pitcher who managed the Yankees in 1930, said he had noticed that Ruffing could dominate for four or five innings while he was with the Red Sox, but tired and lost his stuff because he was “pitching all with his arm.” Shawkey revamped the pitcher’s delivery.4 That wasn’t the only reason for the dramatic improvement; Joe McCarthy took over as manager the next year, and McCarthy consistently fielded strong defensive teams—a pitcher’s best friend.

When Ruffing turned into a star in New York, some writers questioned whether he had been giving his best effort to the Red Sox. But he remembered, “We had kids just out of college, Class D players. Nobody could win with them.”5 A young man in his early 20s could easily have become demoralized pitching for a hopeless team, then snapped out of it when he found himself backed by a lineup that included Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

Twenty-two-year-old Lefty Gomez established himself at the front of the Yankees rotation in 1932 as McCarthy began retooling the aging club. With young catcher Bill Dickey, shortstop Frank Crosetti, and speedy outfielder Ben Chapman in the lineup, the Yankees romped to their first pennant in four years. Gomez won 24 games and Ruffing 18, with a 3.09 ERA, second-best in the AL. He led the league with 190 strikeouts.

Ruffing and Gomez gave the Yankees a pair of aces for a decade. Gomez, three years younger, was the better pitcher when healthy. He led the league in ERA twice and in strikeouts and shutouts three times, but suffered recurring bouts of arm trouble. Ruffing usually racked up more innings and complete games; he completed 62 percent of his career starts, while the average AL pitcher finished less than half. Yankee outfielder Tommy Henrich said, “You know, there wasn’t that much difference between [Gomez] and Ruffing, but Ruffing was always looked upon as the ace.”6

Joe McCarthy agreed; he chose Ruffing to start Game One of six World Series to Gomez’s one. “Sure, he’s the best pitcher around,” the manager said.7 McCarthy scheduled Ruffing’s starts to match him against the Yankees’ toughest challengers. He beat the Tigers 13 straight times from 1937 to 1939. Ruffing was the type of player McCarthy liked best: quiet, consistent, and durable. But the two were not close; Ruffing recalled, “Well, he said hello to me on the first day of spring camp and said good-by to me on the last day of the season. In between he just put the ball in my hand and that was all I wanted.”8

Gomez was a clown and a quipster whose personality eclipsed the stoic Ruffing. (Gomez said the secret of his success was “clean living and a fast outfield.”) One writer called Ruffing “the Coolidge of baseball,” after the president who never spoke two words when one would do. McCarthy remarked, “If Ruffing has nothing to say he doesn’t bother to say it.”9 Ruffing’s closest friends on the Yankees were his roommate, Tony Lazzeri, Frank Crosetti, and Bill Dickey, men who fit the stereotype of the “strong, silent type.” His hometown, Nokomis, had put up a sign at the city limits welcoming visitors to the home of Jim Bottomley, the onetime Cardinal first baseman. When the Chamber of Commerce wanted to add Ruffing’s name to the sign, he told them not to do it because “I might move.”10

On October 6, 1934, Ruffing married a local girl, Pauline Mulholland, whom he had met when she was working in a candy store. He threw a raucous party after the wedding that kept most of the town up all night. Pauline usually attended his starts and heckled the opposition. When she criticized rookie third baseman Red Rolfe for making an error behind her husband, and Rolfe’s wife overheard her, Ruffing told Pauline to apologize. He said, “Rolfe will help me win more games than he ever lost for me.”11

After finishing second from 1933 through 1935, McCarthy assembled a juggernaut in 1936. With Babe Ruth retired, rookie Joe DiMaggio was anointed as the new face of the Yankees. The club won 409 regular-season games in the next four seasons and claimed the World Series championship every year, an unprecedented run of success.

During the Yankees’ four years of dominance, Ruffing won at least 20 games and ranked in the top six in ERA each season. He developed a slider, then a new pitch. Umpire Bill Summers said, “[O]n account of Red Ruffing, the slider got to be the thing.”12 His career was peaking as he entered his mid-30s, an age when most pitchers began to fade. He shared his prescription for keeping fit: “Run, run, run…. Some of the young kids on the Yankees used to kid me about going to bed at 7:30 after running all day long. But as the years went by I noticed I was still up there while they were forgotten.”13 He kept his weight between 208 and 212 on a 6-foot-1 frame.

Ruffing gave the Yankees trouble only when it came time to sign his contract. He was a chronic holdout. After his first 20-victory season in 1936, he didn’t sign until May 1937. With no spring training, he reeled off victories in his first four starts and went on to win 20 again.

By 1939 Ruffing’s reported $28,000 salary was the second highest on the team, behind Lou Gehrig’s $34,000. He won his first seven decisions, the last one the 200th of his career, as the Yankees were running away with their fourth straight pennant. But Ruffing’s elbow was hurting. Without telling McCarthy or the trainers, he began having Pauline massage his arm with a vibrating machine. He said the secret treatment was all that kept him going.14 He started only 28 games and sat out the last two weeks of the season. He finished with a 2.93 ERA, the best in any of his full seasons, and his second consecutive 21-7 record. And he was ready to start, and win, Game One of the World Series against Cincinnati.

In the opening game of the 1942 Series Ruffing held the St. Louis Cardinals hitless for seven and two-thirds innings until Terry Moore singled to right. St. Louis rallied for four runs in the ninth before Spud Chandler relieved to get the last out in the Yankees’ 7-4 win. It was Ruffing’s seventh World Series victory, a record that stood until another Yankee, Whitey Ford, broke it 18 years later. The Cardinals’ ninth-inning rally was the turning point in the Series; they swept the next four games. Ruffing lost the decisive Game Five when he gave up a ninth-inning homer to Whitey Kurowski.

After the Series, with wartime draft calls growing, Ruffing took a job in a defense plant in Southern California, where he had moved. He was summoned for a draft physical, even though he was 37 years old, was missing four toes, and was married with dependents. He and Pauline had a son, Charles Jr., who was called Chuck, and her mother lived with them.

The first doctors who examined him declared him unfit for military service, but an army doctor overruled them. Lieutenant Hal C. Jenkins said Ruffing could handle noncombat duty. Years later Ruffing grumbled, “He would have drafted any ballplayer.”15 At the time he said what was expected of a patriotic American: “There’s only one way to feel. We’ve got a different battle on our hands.”16

On his first day of basic training, as he told it, “A sergeant said to me, ‘Ruffing, I understand you can pitch.’

“‘That’s right,’ I answered. And the sergeant said, ‘Okay, Buddy, let’s see how fast you can pitch this tent.’”17

Ruffing’s noncombat duty was pitching baseballs and leading soldiers’ physical fitness training. He was stationed in California at the Long Beach Ferry Command on a team with big leaguers Max West, Harry Danning, Nanny Fernandez, and Chuck Stevens. In July 1943 he pitched a no-hitter against a Santa Ana Air Base lineup that included his civilian teammate Joe DiMaggio. He compiled a 20-2 record against fellow servicemen. In late 1944 he joined a team of military all-stars that sailed to Hawaii to entertain the troops. Some of the ballplayers went on to other Pacific islands, but Sergeant Ruffing sprained a knee and was sent back to the States. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, the War Department discharged all soldiers and sailors older than 40.

Ruffing took a short vacation with his wife and son before he reported to Yankee Stadium on June 9 to begin shedding some of the 20 pounds he had gained in the army. “I am like a kid with a new toy,” the 40-year-old said. “I keep pinching myself and looking at my civilian clothes.”18 He made his first appearance in pinstripes on July 16 as a pinch-hitter and received a standing ovation. He delivered a single. In his return to the mound 10 days later, he held the Philadelphia Athletics scoreless for six innings before giving way to a reliever. He picked up the first of his seven victories and finished the 1945 season with a 2.89 ERA in 11 starts, capping his comeback year with a three-run homer in his final game. It was his 36th lifetime home run—34 of them as a pitcher, second in history to Wes Ferrell’s 37 at that point. Ruffing was one of the best-hitting pitchers ever; opponents occasionally walked him to pitch to the Yankees’ leadoff batter, Frank Crosetti. Ruffing pinch-hit 257 times in his career, hitting .258/.300/.316.

He opened the 1946 season as a spot starter and more than held his own against the other returning servicemen. By the end of June he was 5-1 with a 1.77 ERA when Philadelphia’s Hank Majeski smashed a line drive that broke his kneecap. The Yankees released him in September. His career appeared to be over.

Not so fast. White Sox manager Ted Lyons, who had just retired from pitching at age 45, thought Ruffing, a mere lad of 41, still had value as a pitcher and pinch-hitter, and signed him for 1947. With 270 victories in his pocket, Ruffing said he wanted to catch Lefty Grove at 300. He didn’t make it. A line drive hit him in the same knee during spring training, and he went on the disabled list. He returned in July for eight more starts, posting a 6.11 ERA, and was released at the end of the season. He finished with a 273-225 record; his 231 victories for the Yankees were a club record until Whitey Ford surpassed him. He probably would have gotten to 300 if he had not lost two-and-a-half seasons to military service.

The White Sox kept him on as a scout, then as manager of their Class-A farm club in Muskegon, Michigan. In 1950 he managed Cleveland’s Class-D team in Daytona Beach, Florida. He spent the rest of the 1950s as a scout for the Indians and moved his family to the Cleveland area. In 1962 the expansion New York Mets, led by former Yankee general manager George Weiss and manager Casey Stengel, hired him as pitching coach. But he complained that the Mets’ pitchers wouldn’t listen to him, perhaps because of the noise of line drives ringing in their ears as they recorded a 5.04 ERA, the worst in the majors. He left after one season.

Ruffing drew as many as half of the Hall of Fame votes only once in his first dozen years on the ballot; 75 percent is required for election. In 1962 new Hall of Famer Bob Feller, writing for a popular magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, named Ruffing, shortstop Luke Appling, and Satchel Paige as players who deserved to be honored in Cooperstown.19 Under the Hall’s rules at that time, baseball writers voted only every other year; on the next ballot, in 1964, Appling was elected and Ruffing’s support jumped to 70 percent. In 1967, his final year on the writers’ ballot, he got 73 percent of the votes and was ushered into the Hall in a runoff. “It’s a dream come true,” he said.20

Many analysts regard Ruffing as a decent pitcher who rode to glory on the coattails of the Yankee dynasty. His reputation rests primarily on his 231 victories and four 20-win seasons as the ace of one of the most powerful clubs in history. His record was a bit better than the Yankees’; he compiled a .651 winning percentage, while the team went .630 with other pitchers.

Looking beyond wins and losses, Ruffing’s 3.80 ERA was the worst by any Hall of Fame pitcher until Jack Morris was elected in 2018. He played in a high-scoring era and said he pitched to the score, coasting when, as often happened, the Yankees staked him to a big lead. His adjusted ERA, equalized for the era and ballparks in which he pitched, is 110, just 10 percent above average. More than 150 pitchers have done better (minimum 2,000 innings), although several Hall of Famers rank behind him, including Don Sutton and Catfish Hunter. Ruffing’s stat lines show little “black ink,” categories in which he led the league: once each in strikeouts, shutouts, complete games, and wins, and twice in strikeouts per nine innings and losses. He was never the equal of the dominant pitchers of his time—Lefty Grove, Carl Hubbell, and Dizzy Dean.

Ruffing’s last years were hard. When he was 68 he suffered the first of several strokes that paralyzed his left side. Pauline loaded him and his wheelchair into their car to make the annual trip from Cleveland to Cooperstown for the Hall of Fame induction ceremonies. He contracted skin cancer and had part of an ear removed. “He was truly a wonderful person,” his wife said, “but he was so stubborn, sometimes he could be a trial. I brought a woman into the house a few times a week to help me with him, but he wouldn’t let anyone touch him except me. Unless I fed him, he wouldn’t eat.”21

Ruffing died of leukemia on February 17, 1986, at a hospital in Mayfield Heights, Ohio. Pauline and their son Charles Jr. survived.

In 2004 a plaque was placed in Yankee Stadium’s Monument Park to honor the pitcher who was lucky to be a Yankee.

Notes

1 Stanley Frank, “As Good as He Has to Be,” Saturday Evening Post, March 16, 1940: 86.

2 The Sporting News, March 4, 1967: 6.

3 New York Times, May 7, 1930: 31.

4 Donald Honig, The Man in the Dugout (Chicago: Follett, 1977), 178.

5 Sporting News, January 21, 1967: 27.

6 Honig, When the Grass Was Real in A Donald Honig Reader (New York: Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 1988), 257.

7 Frank, “As Good as He Has to Be,” 90.

8 Bob August, “Slow Road to Recovery for Red Ruffing at 69,” unidentified clipping in Ruffing’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library.

9 Ted Shane, “Big Red,” American Magazine, August 1939: 44.

10 Richard J. Tofel, A Legend in the Making (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2002), 54.

11 Ibid., 74-75.

12 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside, 2004), 368.

13 Paul Dickson, Baseball’s Greatest Quotations (New York: Collins, 2008), 68.

14 Tofel, A Legend in the Making, 74.

15 William B. Mead, Baseball Goes to War (Repr., Washington: Broadcast Interview Source, 1993), 93. The book’s original title was Even the Browns.

16 New York Times, December 30, 1942: 21.

17 Associated Press-Christian Science Monitor, January 13, 1943: 13.

18 The Sporting News, July 5, 1945: 4.

19 Bob Feller and Ed Linn, “The Trouble with the Hall of Fame.” Saturday Evening Post, January 27, 1962.

20 The Sporting News, March 4, 1967: 5.

21 Quotes from Milton Richman, “Red Ruffing Was a Winner on Mound and At Bat.” Baseball Digest, August 1986: 78. Details about Ruffing’s later life were provided by Charles Ruffing Jr. in emails in 2021.

Full Name

Charles Herbert Ruffing

Born

May 3, 1905 at Granville, IL (USA)

Died

February 17, 1986 at Mayfield Heights, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.