Rene Lachemann

There have been many brother combinations in baseball, including the Nixons (Otis and Donell), the Fords (Gene and Russ), the Sherlocks (Monk and Vince), and the Moriartys (Bill and George). Rene Lachemann was part of a rare brother combination (with his brother Marcel) that both played and managed in the majors.1

There have been many brother combinations in baseball, including the Nixons (Otis and Donell), the Fords (Gene and Russ), the Sherlocks (Monk and Vince), and the Moriartys (Bill and George). Rene Lachemann was part of a rare brother combination (with his brother Marcel) that both played and managed in the majors.1

Rene Lachemann was born on May 4, 1945, in Los Angeles, the son of Swiss immigrants William and Denise Lachemann. William was a chef at LA’s legendary Biltmore Hotel and Denise was a homemaker. Rene was the youngest of four children who included, besides Marcel, brother Bill and sister Denise, the eldest.2 All the Lachemann boys learned the value of hard work from their dad.

“[The brothers] worked alongside their father in the Biltmore kitchen during the summers,” wrote Elliot Teaford in William’s Los Angeles Times obituary. “They arrived at 6 a.m. and worked until 2 p.m. William drove the boys home, then returned to work at the hotel until midnight.”3

As a youngster, Rene was friends with future Los Angeles Dodger Jim Lefebvre. The two started earning their baseball chops early, shagging flies for an American Legion team that was coached by Lefebvre’s father, Ben, and included Rene’s brother Bill and future Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson. That club won a national championship.

Lachemann was an all-city player at Susan Miller Dorsey High School, and was recruited by Dodgers scout Lefty Phillips not to play, but to serve as the Dodgers’ batboy, soon to be joined by his buddy Jim. He also honed his receiving skills by catching batting practice and, being in Hollywood, got to hobnob with Hollywood stars.

“I was on the cover of Confidential magazine,” Lachemann said. ”It showed Doris Day looking over my shoulder into the Dodger dugout.”4

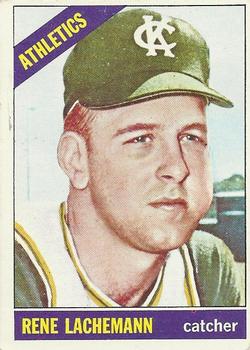

Fortunately, Lachemann had more than a “que sera, sera” attitude about his baseball career, and was signed by the Kansas City Athletics in 1964 at age 19. He bypassed the lower levels of the minors and went right to Class A, with the Burlington (Iowa) Bees of the Midwest League. He batted .281 in 99 games, led in home runs with 24, and finished fourth in RBIs with 82.

Numbers like those will grab attention fast, as will a ringing endorsement from a coach who also happens to be a Hall of Famer. Legendary catcher Gabby Hartnett was the A’s catching coach at spring training in 1965 and liked what he saw in Lachemann, both as a catcher and as an individual.

“That Lachemann, what an arm he has,” Hartnett said. “He’s a sweetheart.”5

Hartnett’s heartfelt assessment of Lachemann’s ability, combined with the impressive numbers he put up in the Midwest League resulted in Rene’s securing a roster spot when the team went north to begin the season.

The A’s were laying the foundation of their 1970s Oakland dynasty. Future stalwarts Catfish Hunter, Blue Moon Odom, Bert Campaneris, and Dick Green all saw some playing time in Kansas City that year, but the A’s were a terrible team, going 59-103. Lachemann got into 92 games, including 75 at catcher. His offensive numbers weren’t spectacular, a .227 batting average with 9 home runs and 29 RBIs, but he received a backstop’s ultimate compliment when the team’s pitchers said they liked throwing to him.

“The catching of Rene Lachemann … has drawn praise from the [A’s] pitching staff,” wrote Joe McGuff. “Not only do the pitchers like to throw to Lachemann, they say he calls a good game.”6

That praise didn’t mean much when spring training convened in 1966. Veteran Bill Bryan was the number-one catcher in 1965, and the A’s had acquired Phil Roof from Cleveland in the offseason. The assessment on Lachemann was that he had difficulty getting quick throws off and was unable to hit big-league pitching. He was sent to the Mobile A’s of the Double-A Southern League and made only five plate appearances with Kansas City that year.

At Mobile Lachemann had respectable if not outstanding statistics, batting .256 with 15 home runs and 65 RBIs. But more importantly, one of his teammates was Tony La Russa, and the two would work together years later on another dynastic A’s team.

Lachemann crossed the 49th Parallel in 1967 to play for the Vancouver Mounties of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, where he hit .222 with 6 homers and 53 RBIs in 123 games. He got some extra work in after the PCL season ended, playing for the A’s entry in the Arizona Fall League.7 His manager on the AFL team was John McNamara, for whom Lachemann later coached on the 1986 American League champion Boston Red Sox.

Maybe the fact that he wasn’t always getting his man at second base compelled the A’s – now in Oakland – to return Lachemann to the Mounties for 1968. They called him up briefly in late April when injuries hit catchers Phil Roof and Jim Pagliaroni. Lachemann started 15 games, but he got only 9 hits in 60 at-bats for a .150 average with no home runs and 4 RBIs. He played his last game in the majors on June 8. He did somewhat better in Vancouver, hitting .249 in 62 games with 4 home runs and 14 RBIs.

The next four years were frustrating for Lachemann. From 1969 to 1972, he produced decent numbers with the A’s new Triple-A affiliate, the Iowa Oaks of the American Association. In 1969 he hit 20 home runs and had 66 RBIs. After an off year in 1970 (5 homers, 20 RBIs), he hit 17 home runs and had 48 RBIs in 1971 and 11 homers with 37 RBIs in in 1972. Lachemann was also playing around the infield more often than he was behind the plate. In 1969 he played more games at first base (62) than he did at catcher (45). In 1970 he didn’t catch at all, but saw time at first, second, and third. That’s really terrific if you’re out with your girlfriend but not so great if you want to be a major-league backstop. He wore the tools of ignorance only 21 times in 1971 and 1972. It was clear that in baseball terms Lachemann’s biological clock was ticking. Then a job offer and some advice changed the course of his career.

The next four years were frustrating for Lachemann. From 1969 to 1972, he produced decent numbers with the A’s new Triple-A affiliate, the Iowa Oaks of the American Association. In 1969 he hit 20 home runs and had 66 RBIs. After an off year in 1970 (5 homers, 20 RBIs), he hit 17 home runs and had 48 RBIs in 1971 and 11 homers with 37 RBIs in in 1972. Lachemann was also playing around the infield more often than he was behind the plate. In 1969 he played more games at first base (62) than he did at catcher (45). In 1970 he didn’t catch at all, but saw time at first, second, and third. That’s really terrific if you’re out with your girlfriend but not so great if you want to be a major-league backstop. He wore the tools of ignorance only 21 times in 1971 and 1972. It was clear that in baseball terms Lachemann’s biological clock was ticking. Then a job offer and some advice changed the course of his career.

As the 1972 season wound down, Oaks general manager John Claiborne approached Lachemann about a job managing in the A’s system. Still hoping for a ticket to “The Show,” Lachemann initially turned the offer down. That’s when Iowa manager Sherm Lollar suggested that the give the opportunity a second thought.

“If I was you, Lollar supposedly said, I’d take a look around the clubhouse and reconsider,” wrote Tracy Ringolsby.8

Lachemann looked around and saw that there were plenty of players in the clubhouse younger than he was. It was clear that he wouldn’t return to the majors and that at 27 he was an old man. “I knew when the pink slips came out next spring, the older guys would get them,” he said.9

Lachemann took Claiborne up on his offer and took the helm in Burlington in 1973 on his climb back up the minor-league ladder. He managed for three years at Class A, attaining only one winning season, when his Burlington Bees went 61-59 in 1974. He had his second, and last, winning season as a manager – at any level – in 1976 when he guided the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Double-A Southern League to a 70-68 mark, winning the league’s Manager of the Year Award.10

That honor helped Lachemann garner a promotion for 1977 to Triple-A with the PCL’s San Jose Missions, who that year were still affiliated with the A’s. The Missions finished with a 64-80 record, but the Seattle Mariners chose to keep Lachemann as skipper when they took over the club in 1978. He stayed when the club switched its Triple-A affiliation to the Spokane Indians for 1979-80, having turned down an offer from A’s owner Charlie Finley to manage the big-league club when Finley wouldn’t give him sole authority over making out the daily lineup card.

The Mariners were entering their fifth season of existence when the 1981 season opened. They hadn’t come anywhere close to the .500 mark in any of their previous four years, which is understandable in a new team, but they weren’t getting any better. They went 59-103 in 1980, and had got off to an abysmal 6-18 start in 1981 under manager Maury Wills. Management decided that with this Wills there was no way, so they fired him on May 6 and brought in Lachemann. Lachemann was deemed an “interim” manager, but responded to a reporter’s query that the title didn’t bother him. “Interim?” he said. “I feel any manager in the big leagues is that way. If you don’t do the job, you’re gone.”11

The team initially responded well to the change, winning Lachemann’s debut game 12-1 over Milwaukee, which started a modest four-game winning streak. They followed this up with a four-game losing skid on their way to a 44-65 combined record in the strike-shortened season. By Mariners standards that was pretty good, as was Lachemann’s 38-47 mark. After the season, the team told him he could erase the “interim” from his business cards by signing him to a one-year contract for 1982 with options for two more years. Mariners players, who liked having him as their boss, welcomed the news.

“If you have a tough time playing for Lach, you’d have a tough time playing for anybody,” said designated hitter Richie Zisk. “He’s very up front as far as letting him know where he stands. “He gives them an honest answer to any question they ask.”12

The Mariners had their first 70-plus-win season in 1982, going 76-86 and finishing fourth in the American League West. They still had offensive woes, finishing 12th out of 14 AL teams in runs scored, with 651. Their pitching buoyed them up with a 3.88 team ERA, fourth in the league. The team played very well before the All-Star break. On July 8 the Mariners had a 45-37 record, three games out of the division lead, but they plummeted in the second half. In a tirade the night before the team broke its record for victories in a season, pitcher Bill Caudill praised Lachemann and put the blame for the decline squarely on his teammates’ shoulders.

“That man [Lachemann] makes me want to go out and do well,” Caudill said. “He and his coaches have done everything in the world to make us play. It’s a shame some people just don’t want to do more for him and themselves.”13

Despite the team’s slide, the Mariners kept Lachemann on for 1983. Well, for part of it, anyway. The poor play that plagued the team in the last half of 1982 continued; a 3-15 slump that included an eight-game losing streak, led to Lachemann’s firing on June 25. Del Crandall replaced him, and Seattle limped to a 60-102 record and a last-place finish.

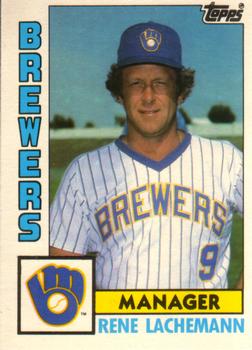

The unemployment checks didn’t come for long. The Milwaukee Brewers, who went to the World Series in 1982, fired manager Harvey Kuenn after going 87-75 in 1983 and chose Lachemann to replace him for 1984. In fact, Brewers general manager Harry Dalton said that he hadn’t considered anybody else.

Maybe he should have. The Brewers were a disaster that year, going 67-94 and finishing last in the American League East. Injuries were part of the problem; future Hall of Famer Paul Molitor blew out his right elbow and played in only 13 games. The offense as a whole was terrible, ranking last in the league in runs scored with 641. Cecil Cooper and Ted Simmons were both 100-RBI men in 1983, with Cooper having a team-leading 126. The two combined didn’t reach that total in 1984 (Cooper had 67 and Simmons 52). The Brewers were mathematically eliminated from playoff contention on August 28. Lachemann was eliminated from his job on September 27 with three games left in the season. To his credit, he stayed on for the Brewers’ last series of the year (in which they took two out of three from the Toronto Blue Jays).

The ink was barely dry on Lachemann’s pink slip when one of the connections he made in his baseball travels came though with a job offer. John McNamara was named manager of the Red Sox for the 1985 season and hired Lachemann as his third-base coach. After two years in Boston, Lachemann decided he wanted to be closer to his home in Arizona and got a job as first-base coach with the up-and-coming A’s under his old friend Tony La Russa. He finally reached the summit in 1989 when Oakland won the World Series, sweeping the San Francisco Giants.

Lachemann was rumored to be in the running for managerial positions with various teams while with Oakland. He was a finalist for the skipper’s job with the White Sox in 1991 but Gene Lamont ultimately got the offer. Lachemann had to wait until the National League added two teams for the 1993 season for another managing opportunity, when the brand new Florida Marlins hired him to guide them through their inaugural season. General manager Dave Dombrowski thought of Lachemann as a very good baseball mind who might have been too young and inexperienced for the job when he managed Seattle and Milwaukee.

“He was 36 when Seattle hired him,” Dombrowski said. “I think he’s learned from his managerial experiences, and I think it’s been beneficial for him to be a coach for the Red Sox and for Tony La Russa in Oakland.”14

One thing Lachemann probably didn’t learn from La Russa was nepotism. He learned it somewhere because his first hire as manager was his brother Marcel as pitching coach. This was actually a legitimate choice because Marcel had held the job with the California Angels the previous 10 seasons.

Being the manager of an expansion team is a no-win situation. Well, very few wins anyway. The Marlins went 64-98 in their first year, which isn’t bad by expansion-team standards when you consider that the 1962 Mets lost 120, the 1969 Expos and Padres each lost 110, and their expansion cousins, the Colorado Rockies, lost 95. Despite the record, Lachemann proved he was a winner when he and his wife, Laurie, whom he married in 1964, started the “Lach’s Kid’s” program. Lach’s Kids gave inner-city youngsters the opportunity to attend a Marlins game, sit in the dugout, talk ball with Lachemann, scarf hot dogs, and take home souvenirs, all at his expense.

The club improved slowly but surely the next few seasons. It went 51-64 in the strike-shortened 1994 season and 67-76 in 1995. Unfortunately for Lachemann, the Rockies went 77-67 that year and made the playoffs as the wild card.

Clearly the Rockies were improving faster than the Marlins. The Marlins got off to a good start in 1996, and were at .500 (31-31) on June 10. Even on June 29, they were near the break-even point at 39-40, but then they lost seven in a row, leading to Lachemann’s firing on July 7.

Lachemann had time to deposit a few unemployment checks this time, but wouldn’t you know it? His old friend La Russa was now managing the Cardinals and needed a third-base coach. Lachemann was hired for the 1997 season. He stayed there until after the 1999 season, and then began a baseball odyssey of sorts. He served as bench coach with the Cubs (2000-2002), Mariners (2003-2004), and A’s (2005-2007). In 2008 he moved back to the minors as hitting coach for the Colorado Springs Sky Sox, the Triple-A affiliate of the Rockies in the Pacific Coast League, and retained that position until 2012. He was called back up to the majors in 2013 with the Rockies to coach first base.

As of 2014 Lachemann was still in Denver as the catching and defensive positioning coach and living in Scottsdale, Arizona, with Laurie during the offseason. They have two sons, Jim and Britt, and three grandchildren.

Last revised: December 1, 2016

This article originally appeared in “The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Leslie Heaphy.

Sources

Arizona Republic (Phoenix)

Baseball-almanac.com

Baseball-reference.com

Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel

Galveston Daily News

Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times

Imdb.com

Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette

Kansas City Star

Kansas City Times

Los Angeles Times

San Bernardino County (California) Sun

Santa Cruz (California) Sentinel

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

Sports Illustrated

The Sporting News

Ukiah (California) Daily Journal

Notes

1 Marcel managed the California Angels from 1994 to 1996.

2 Bill was a longtime manager in the San Francisco Giants and California/Anaheim Angels organizations.

3 Elliot Teaford, “William Lachemann Sill Providing Inspiration for Sons,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 1995.

4 Gordon Edes, “Rene Lachemann: This Is Your Life,” Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, October 25, 1992.

5 Joe McGuff, “Gabby Hartnett Avoids Trademark of Catching Trade,” Kansas City Star, March 9, 1965.

6 McGuff, “A’s Hoping There’s Still Magic In Veteran Mossi’s Left Wing,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1965.

7 In an October 18, 1967, article on the Arizona Fall League’s A’s squad, George Chrisman Jr., a writer for the Arizona Republic, said Lachemann was Canadian.

8 Tracy Ringoldsby, “Patient Lachemann Gets His Chance,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1981.

9 Ibid.

10 In an effort to improve his managerial skills, Lachemann began managing in the Caribbean after the 1976 season, and continued doing so until 1981. He had his best year as a manager in 1978 when he guided Los Indios de Mayagüez of the Puerto Rican Winter League to the Caribbean Series championship, and earned the league’s Manager of the Year Award.

11 United Press International, “Seattle Mariners Fire Maury Wills,” Ukiah Daily Journal, May 7, 1981.

12 Ringoldsby, “Lachemann Led M’s Turnaround,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1981.

13 Ringoldsby, “Second-half Plunge Dims M’s Record,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1982.

14 Associated Press, “Lachemann making no predictions on Marlins,” Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette, October 24, 1992.

Full Name

Rene George Lachemann

Born

May 4, 1945 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.