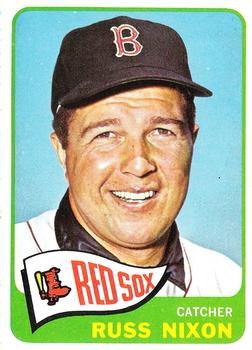

Russ Nixon

Russ Nixon spent more than half a century in baseball. A catcher who played 12 years for the Red Sox, Indians, and Twins, he went on to coach and manage at levels from rookie ball to the major leagues, with five seasons as a big-league manager.

Russ Nixon spent more than half a century in baseball. A catcher who played 12 years for the Red Sox, Indians, and Twins, he went on to coach and manage at levels from rookie ball to the major leagues, with five seasons as a big-league manager.

The son of farmers Thomas and Edith Nixon of Crosby, Ohio, he and identical twin brother Roy were born on February 19, 1935, in Cleves, Ohio. Roy, a first baseman, played minor-league ball for five seasons in the Cleveland Indians system, from 1953 through 1957, reaching as high as A-level ball at Reading. He had a .299 career average. Catchers were more in demand than first basemen, Roy explained. “I gave it five years. I never got a shot at the bigs. In those days, they were looking for first basemen to be big home run men. I was a line-drive hitter, like Russ.”1

It was apparently their grandfather’s love of baseball that kindled their interest. At a very young age, the two boys had built a baseball field on the farm. Russ’s wife Glenda said, “I do know that one grandfather loved baseball. All the family were dairy farmers. He was, too, but he loved baseball and he fixed a field — a field of dreams, I guess — for them when they were very young. He also got them to hit left-handed. He thought they would have an advantage there. It probably did, because they weren’t the fastest guys.”2

Both graduated from Cincinnati’s Western Hills High School in 1953, the same school that Pete Rose later attended. In all, 11 big leaguers came through the school, including major-league managers Don Zimmer and Jim Frey; with Nixon, that’s a trio of big-league managers from one school.

The 1951 high school team won the Ohio state championship. The Nixons had also attracted attention in 1951 as part of the American Legion Junior team from Cincinnati that made it to the finals and finished third; Russ batted .310. Both were 6-foot-1 and listed at 190-195 pounds. Russ threw right-handed but batted from the left side, as did Roy.

In September 1952, both Roy and Russ were on the Robert E. Bentley Post No. 50 team from Cincinnati that won the national championship in Denver, coached by Joe Hawk. Russ was co-captain of the team, hit .500 in the title series, and was unanimously voted Player of the Year.3 Roy was named to the American Legion junior all-star team. Russ was invited to Ebbets Field and threw out the first pitch of the 1952 World Series between the Dodgers and Yankees. In June 1953, both Nixons were invited to Cleveland and signed by Indians scout Laddie Placek, right out of high school, and assigned to Corning in the PONY League.4 In a workout in Cleveland, Russ was able to catch Bob Feller.

Both were sent to Green Bay in the Class-D Wisconsin State League. Russ played in 43 games and recorded a .336 batting average. Roy had gotten off to the faster start, but finished with a .253 average, playing a few more games — Russ had had to travel to Cooperstown to be honored on July 27 for his American Legion award. Green Bay won the league pennant.

The two brothers continued in tandem in 1954, assigned to the Jacksonville Beach Sea Birds (Class-D Florida State League.) Roy had an excellent year, batting .324 with 91 RBIs but brother Russ one-upped him with a league-leading .387 average and 96 RBIs. From that point forward, their career paths diverged. In 1955, Roy played in Class C but Russ was advanced to Class B where he played in the Three-I league for Keokuk and excelled again, batting .385 (he had a 32-game hitting streak at one point and again led his league). In 1956, Russ was jumped to Triple-A Indianapolis, and there he hit .319

Russ was on the San Diego roster through most of 1957 spring training and worked closely with Jim Hegan, who he credited with teaching him a lot about catching.5

In his April 20, 1957, major-league debut in Detroit, after catching the seventh and eighth, Nixon singled to right field off the Tigers’ Frank Lary in his first time at bat.

Catching duties for the 1957 Indians were more or less equally shared by Nixon (62 games), Hegan (58), and Hal Naragon (57). Nixon got significantly more plate appearances and his .281 batting average was substantially more than the others. He homered twice and drove in 18 runs. The team finished in sixth place under manager Kerby Farrell.

Nixon played winter ball in Havana for Bobby Bragan’s Almendares team, suffering a badly sprained leg in December, initially feared to be a broken leg.

Nixon became the regular catcher in 1958, appearing in 113 games. It was his best season, with a .301 batting average. He homered nine times and drove in 46; all three figures were career bests. (He also struck out 38 times, more than any other year.)

It was also a very good year defensively. He threw out 40% of the runners attempting to steal, a career best, and had a fielding percentage of .991. All told, Nixon posted a career .988 fielding percentage and threw out 29% of the runners attempting to steal. (When he was the one on the basepaths, he attempted seven stolen bases over the course of his career and was thrown out every time. He holds the major-league record, playing 906 games without a stolen base.)

There was such turnover on the Tribe at the time that when Nixon was in Tucson for his fourth spring training in February 1959 and turned 24 years old, he was one of the veterans on the team. Only seven others in camp were older. He had spent the offseason working on the loading dock of a Cincinnati trucking company where brother Roy worked, to help provide for his wife Glenda (Carder) and two children.

Roy was driving trucks in Cincinnati for the Hudepoel Brewing Company, eventually becoming its traffic manager.6

Russ and Glenda had married in 1954. She remembers first seeing Russ (and his brother Roy) when she was in the seventh grade. “Our school played their school in Elizabethtown, a little town just outside of Cincinnati along the Ohio River. He and Roy were on the team. I noticed these two kids wearing bib overalls. He was a catcher there and I think Roy was a pitcher. I noticed them for sure.”7

Glenda’s father Glenn Carder ran a Knothole team. “He was very active in Delhi Township in Cincinnati, creating the Knothole teams there. He was in it for a long time, 25 years maybe. Pete Rose played for my father’s Knothole team in Cincinnati. So we knew each other, and still do. We used to go pick him up. At that time he was a very shy kid. He changed. Russ was with him in Montreal and in Cincinnati. He was still playing and Russ was a coach.”8 Glenda and Russ ended up going to the same high school.

In 1959, Nixon slumped badly at the plate. He got off to a slow start, and for three months from mid-May to mid-August never got his average higher than .195. At the end of June, he was only hitting .148. He was likely pressing too hard; after an August 17 groin injury sidelined him for a couple of weeks, he came back and finished with a strong September which saw him pull his average up to .240 by season’s end. Manager Joe Gordon claimed some of the credit, saying he had advised Nixon to start swinging a heavier bat.9

Despite his average dropping 60 points, Nixon held out for a raise from GM Frank Lane. Finally, Lane promised him a raise if he appeared in 100 games — and then traded him to the Boston Red Sox in mid-March for established catcher Sammy White and first baseman/outfielder Jim Marshall. The trade was described as “two catchers getting out of two doghouses” — neither Nixon nor White popular with their respective GMs. Lane reportedly had been demeaning Nixon, calling him “Pudgy Wudgy.”10 Both GMs, Lane and Bucky Harris of the Red Sox, considered Nixon the best player in the trade.11

It turned out that White did not like the trade and refused to report to Cleveland. On March 19, he announced his retirement instead. It needed to be determined whether White was retiring from the Indians or retiring from the Red Sox. Acrimony developed between the two teams, Harris calling Lane “vicious.”12 Nine days after the trade, Commissioner Ford Frick voided the deal and sent Nixon back to the Indians. He didn’t want to go, and worked out with the Red Sox for another day before returning to the Indians. The Red Sox had signed him to a new contract — up to $15,000 from his $11,000 Indians salary, and on March 30 Nixon asked Frick for a ruling as to what salary he would be paid.13 On April 5, Nixon and Lane came to an agreement. “No, he didn’t give me the raise,” Nixon said, “But he made me feel I was wanted on the ballclub and that was more important. I didn’t feel that way before.” It’s likely there was some promise of him ultimately getting the increase.14

He was 2-for-4 on Opening Day 1960. On May 12, his game-winning home run in the 11th inning won that day’s game. A month later, batting .244, he was traded to the Red Sox on June 13 with Carroll Hardy for Ted Bowsfield and Marty Keough. The next day’s Plain Dealer story was headlined “Nixon Gets Wish, Back With Boston.” Nixon was the key to the trade; the Red Sox needed a solid catcher.15 And Nixon let it be known he was glad to be free from Frank Lane: “Was I ever glad to get away from that man,” he said.16 New Red Sox manager Mike Higgins, who had just replaced Billy Jurges, was very pleased. He had been after Nixon for a couple of years, saying, “As of right now, I will consider Nixon my Number One catcher.”17

For the rest of the year, despite a ball striking him in the mouth, a virus, and a brief knee injury, Nixon hit like he was happy again, nearly matching his 1958 output with a .298 batting average in 80 games for the Red Sox.

There had been one moment of some interest on August 15 in Washington. President Dwight Eisenhower attended the game and saw Truman [Clevenger] strike out [Russ] Nixon in the second inning.

Over the winter, he had his tonsils removed and, somehow, he lost the look that had bothered Frank Lane. He no longer looked like someone who ate too much ice cream and cake.18 In 1961, Nixon was the principal backup for catcher Jim Pagliaroni, platooning against right-handed pitchers (though he was not a pull hitter and tended to hit better to left and center fields).19 Nixon appeared in 87 games, with 263 plate appearances, and hit for a .289 average but only managed a meager 19 RBIs, down from 33 the year before. Yet his hitting was ranked higher than his work as a catcher. “Nixon is a good hitter, but not a good catcher” wrote Larry Claflin a few weeks after Chuck Essegian slid into home and knocked the ball out of Nixon’s glove, giving the Indians a 9-8 win over the Red Sox.20

In 1962 the number of games in which he appeared dropped to 65; he missed more than five weeks from May 20 to June 27 due to a fractured right hand, struck by a foul tip. Mike Higgins also favored Pagliaroni and Bob Tillman when the Sox were in Fenway. There was one game, though, on May 4 at Fenway, when he pinch-hit for Mike Fornieles in the fourth inning of a game against the White Sox; he singled and scored. The Red Sox sent 16 batters to the plate in the inning, and so Nixon came up again, and once again singled and scored. Despite declining by more than 100 plate appearances, he matched the 19 RBIs and hit .278. In November, Pagliaroni was traded to the Pirates. That elevated Nixon from the #3 catcher to one of the top two.

Working under manager Johnny Pesky, Nixon’s 1963 totals reflect the most games (98) in a season over the seven seasons he spent with the Red Sox. He appeared in two more games than Tillman, but Tillman had 343 plate appearances to Nixon’s 316. He hit .268, and drove in 30 runs. One hit that Jim Bouton rues is Nixon’s leadoff single in the ninth inning against the Yankees on August 27 in the first game of a doubleheader; Bouton had a no-hitter through eight. The single was Nixon’s fifth consecutive hit. Before the winter meetings, GM Higgins said, “We will try very hard to get a catcher,” thereby indicating his sense that the Sox could do better.21 Other clubs beat Boston to making deals for catchers on the market, though, and by January 1964 Johnny Pesky let it be known that Nixon was his #1 catcher for the year to come. “I’ll believe that when I see it,” Nixon said. “I never get the No. 1 job until the middle of July. One time I’d like to go to spring training with the job, but I doubt it will happen.”22

Though he got into 81 games in 1964, he’d suffered a collision with Dick Stuart in the springtime and a groin pull in the early going. He was used often as a pinch-hitter and was batting .400 at the end of May, and .338 at the end of June. Indeed, the highlight of his season may have been the two-run pinch-hit home run off Tommy John with two outs in the bottom of the ninth on June 26, giving Boston a 3-2 win over Cleveland. In mid-July, he went into a prolonged slump, and he never quite recovered. His batting average for the season fell off significantly to .233.

Over the winter, there was little doubt that the Red Sox had him on the trading block, but they were never able to pull together a satisfactory deal. After four failed pinch-hitting attempts to kick off the 1965 season, he was placed on waivers and no team claimed him despite the fact that he was a career .276 hitter. As an eight-year veteran, he could have refused assignment to the minors, but he agreed to go to Triple-A. He spent 31 early-season games with Toronto, where he hit .323 before being brought back to Boston on June 22. Used less often (59 games) in 1965, he boosted his average back up to .270 for the year but only drove in 11 runs in 147 times at the plate. Nonetheless, it was evident the Red Sox were again trying to move him over the winter, as much as anything to make room for the up-and-coming Mike Ryan.

Late in spring training 1966, he was packaged in an April 6 trade, sending Nixon and Chuck Schilling to the Minnesota Twins for left-handed pitcher Dick Stigman and a player to be named later, a minor leaguer who never made the majors. Stigman started 10 games and relieved in 24 others; after 81 innings, he was 2-1 (5.44). It was his last season in the big leagues.

Nixon was a backup catcher again for the Twins, behind Earl Battey, sharing time with Jerry Zimmerman. He accumulated 106 plate appearances in 51 games, hit .260, but only had seven RBIs all season, fewer than two of the pitchers (Jim Kaat and Mudcat Grant).

The 1967 Twins, eliminated from the pennant race by the Impossible Dream Red Sox in the final game of the season, saw a more productive Russ Nixon. Though his average fell to .235, he drove in 22 runs. He was in 74 games, including the final game, in which he pinch-hit and hit a fly ball to left field off Jim Lonborg. He was due up with two out in the ninth inning, but was lifted for Rich Rollins, who lofted a high popup to shortstop Rico Petrocelli.

In another deal late in spring training, the Twins released him outright in early April 1968, and he was promptly signed to a minor-league contract as a free agent by the Red Sox, basically for insurance purposes. It proved to be his last season as a player in the big leagues. He began the season as a catcher/coach with Pittsfield in the Eastern League. It was Double-A ball and he only hit .212, also suffering a broken leg in the early going. When Elston Howard suffered a sore elbow, Nixon was called back up to the Red Sox. He was only used in 29 games, all but one in July and August. For Boston he hit .153 and drove in six — half of them in his first game, against the Twins, on a bases-clearing double in the top of the ninth that gave the Red Sox a 6-5 win. After the season, his contract was assigned to Louisville.

Though drafted by the White Sox in December and signed to a White Sox contract for 1969, Nixon was released on March 30 and was out of baseball for the year.23

On February 14, 1970, the Cincinnati Reds announced that they had hired him as a minor-league catching instructor. “I’m really happy to be back in the game,” he said. “These past ten months away from it just haven’t been the same. I guess it’s a natural enough reaction after playing for 16 years. I’ve looked forward to entering this phase of baseball and, believe me, it’s a real break to be able to start with the home town club. The Reds have a fine organization and I’m eager to grow with them.”24 The Nixons had four children and lived in Cincinnati. The plan was for him to then coach with Asheville and take over in June as manager of the short-season Northern League’s Sioux Falls Packers, which he did.

For the five seasons after that — 1971 through 1975 — Nixon managed the Single-A Tampa Tarpons of the Florida State League. In 1974, Tampa finished first in the North Division. In December 1975, while he was managing in Mexican winter league ball, Nixon was named a coach of the Cincinnati Reds, replacing Alex Grammas. When manager Sparky Anderson was fired in November 1978, Nixon was kept on under incoming manager John McNamara and was asked to take over third-base duties in late June 1979.

Nixon continued to coach for the Reds through 1981, and into the 1982 season through July 20, when he was named to take over for McNamara, fired from the 34-58 team, the second-worst record in baseball at the time. “I’d like to get back in the winning habit,” Nixon said on being hired. “I don’t think anybody here accepts it, but I think we’ve found ways to lose.”25 McNamara left a gracious note on his desk for Nixon. The team only did marginally better — a .386 wins percentage as opposed to .369. Just before the season was over, Nixon was hired again for 1983.

He managed the Reds in 1983 for the full season but the team finished last in the NL West, 74-88 (.457). As the Reds changed top management, Nixon was also let go at the end of the season, returning to his 52-acre farm where he raised Arabian horses. Three days later he was hired to coach for the Montreal Expos. Nonetheless, it hadn’t been an easy experience being fired. When the Expos first visited Cincinnati in 1984, he said, “I don’t think you ever fully get over something like that. I don’t see how you could. Things like that take a while. It was trying times here, I’ll say that. But I don’t regret anything I said or did.”26

Years later, Glenda Nixon said, “We loved the Red Sox organization. We had so much fun there. And made lifelong friends with people in the military, actually, at Pease Air Force Base [in New Hampshire]. Several of the players did. We loved the Reds and the Red Sox.”27

He was the third-base coach for the Expos for all of 1984 and into May 1985. He remained on the coaching staff through the full 1985 season and was asked to stay on as hitting instructor for 1986, but elected to decline the offer. “I want to manage again,” he said, “and I don’t think there’s any secret about that.”28 He wanted a position which kept him on the field, and so accepted the third-base job with the Atlanta Braves.

In 1986 and 1987 he coached for the Braves, but his ambition to manage again may have been too obvious for the taste of Braves manager Chuck Tanner. Gerry Fraley, writing in The Sporting News, said of Nixon’s October 1987 decision to leave the club, “Never comfortable with Nixon because of his desire to manage, Tanner tried to have him replaced after last season, General Manager Bobby Cox intervened, but Tanner got his way this time…Tanner would not discuss the reasons for Nixon’s departure.”29

Nixon had been offered a job managing in Greenville in the Double-A Southern League, a big step backwards. It was at first thought he would decline the position, but he accepted and Greenville got off to a very good start, in first place by mid-May.

After 39 games in 1988 (12-27), Tanner was fired in Atlanta and Bobby Cox hired Nixon to take his place beginning on May 23. Tanner had worked for 17 years as a manager in the majors. “This is the first time I’ve ever been fired in my life,” he said.30 He hadn’t seen it coming. Nixon was not diplomatic in his remarks about Tanner. “Chuck Tanner fired me…I’m not a b.s. artist. They’re going to get what they see. Players want that. If they’re playing lousy, they want to be told that. And if they’re going good, they want to be told that, too. I know there are times when you can be diplomatic, but you don’t have to be a liar about it.”31

The 1988 team barely won more than a third of its games under Nixon. That said, he hadn’t promised a quick fix. In July 1988, he had said, “Realistically, our situation is that it will be three years before we can think about being contenders.”32 Big-league managers don’t often get that much time to rebuild. When the Braves failed to win 40% of their games in 1989 (62-97, .394), it’s likely there was a little restlessness. He’d been signed to manage in 1990 as early as August 1989, with Cox saying, “To me, Russ has done a good job.”33

Sixty-five games into the 1990 season, with the team at 25-40 (.385), Nixon was fired. He wasn’t happy about it when the Braves put out word that he was relieved at being replaced. “I don’t know where this is coming from. The only relief was about a charade being over. Heck, I’ve been expecting it. It’s been evident the last two weeks. One of the bullets was going to get me, they’ve been shooting so many at me.” He added that the Braves were “a horse**** organization.”34 He’d had a sense it was coming, though. After the Braves had won the second game of the June 12 doubleheader against Cincinnati, he’d said, “They pulled me off death row with that one, didn’t they?”35 Bobby Cox, the GM, took over as field manager. After the season, John Schuerholz came in as VP and GM, and Cox remained as manager. A couple days after being fired, Nixon had cooled down and said he harbored no animosity. (As it happens, the Braves went from worst to first in 1991.)

Nixon had scattered work from this time forward. In 1991 he managed for the Portland Beavers in the Pacific Coast League. In 1992 he was the bench coach for the Seattle Mariners under manager Bill Plummer, but come October Plummer and his whole staff were fired. In 1994 he managed the Las Vegas Stars in the PCL for one season.

From 1995 through 1997, he was the director of minor-league instruction for the San Diego Padres, the Director of Player Development the latter two years.

He was back with the Cincinnati Reds organization from 1998 through 2000, serving as a catching instructor and also manager of the Billings Mustangs in the rookie-level Pioneer League. In 2001 and 2002 he was catching instructor in the Pittsburgh Pirates organization.

He then managed for three years in the Houston Astros chain — in 2003 for Lexington, Kentucky; in 2004 for Salem, Virginia; and in 2005 for the Greeneville Astros in Tennessee. That last assignment was in the rookie Appalachian League. “It’s kind of remote up here,” he said by way of understatement. “But baseball is baseball…I enjoy this. I really do. The game itself is what’s important, not me or anyone else. All these kids have a dream of making the big leagues, and I’m here to help them as much as I can. That’s enough to satisfy me.”36

Interviewed by Bill Ballew in 2006, Nixon said, “This game and the kids in it keep me young. I feed off their energy and the fun they’re having.”37

Nixon worked as a minor-league catching advisor for the Texas Rangers from 2008 to 2011, working mostly with minor-league catchers at the Rangers’ Arizona complex. John Blake of the Rangers says, “He was brought aboard by team President Nolan Ryan, who knew Nixon from his days working with the Astros and as a big-league manager.”38

“It was only about a year after he retired that he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s,” said Glenda Nixon. “He stayed at home until 2015, in the fall, and then we found a place close to where we lived that was very good, one of the group home things. He was really happy there. I think six years is kind of what happens, according to what they told me. We worked with Cleveland Clinic on it. All of a sudden, within a week, he just went downhill. And he got a lung infection.”39

Russ Nixon died in Las Vegas on November 9, 2016. He was survived by his wife, Glenda, their daughters Rebel, Misty, and Samantha, and their son, Christopher, as well as his brother, Roy, and several grandchildren.

“I think we were really lucky,” recalled Glenda Nixon in late 2017. “We got to see a lot of the special occasions, like Hank Aaron’s special home run, and Pete Rose’s hits. We had a really good time in baseball. I have to tell you it was much nicer than it is now. We had to wait forever after a game, because the guys just hung around in the locker room together talking baseball and having a beer. We would get together socially afterwards. I’m not sure a lot of that happens any more.

“Russ always said baseball is bigger than anybody and you’re never going to lose it. I think he was right. I’ve loved baseball my whole life, so I was very happy how things turned out for us.”40

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Nixon’s player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Stew Thornley.

Notes

1 Lonnie Wheeler, “West High Legend Adds Nixon Chapter, Cincinnati Enquirer, undated clipping from 1976.

2 Author interview with Glenda Nixon on December 19, 2017.

3 Jerry Olnick, “Russ Nixon Named Player of Year After Hitting .500 in Title Series,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1952: 44.

4 “Tribe Gets Into Twins Act, Signs Russ and Roy Nixon,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1953: 37.

5 Harry Jones, “Hegan Helps His Understudy Catch on Fast with Indians,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 7, 1957: 170.

6 Lonnie Wheeler.

7 Glenda Nixon interview.

8 Ibid.

9 Harry Jones, “’Little Guy’ Temple Wants To Prove He Can Play for Flag Contender,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 1, 1960: 25.

10 Larry Claflin, “Red Sox Brass Feel Nixon A ‘Steal’,” Boston American, March 17, 1960: 34.

11 Roger Birtwell, “Sox Trade White for Indians’ Nixon,” Boston Globe, March 17, 1960: 37.

12 Associated Press, “Harris Blasts Lane, Says He’s ‘Vicious’,” Atlanta Constitution, March 22, 1960: 29.

13 Harry Jones, “Batting Around,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 31, 1960: 34.

14 Harry Jones, “Batting Around,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 6, 1960: 36.

15 Bill McSweeney, “Nixon Key In Hose-Indians Two for Two Deal,” Boston Daily Record, June 14, 1960: 6.

16 D. Leo Monahan, “Sox Russ Nixon Turns On Lane,” Boston Daily Record, June 16, 1960: 28. The Red Sox restored the $3,000 they had given Nixon when they thought they had him earlier in the year.

17 Roger Birtwell, “Mike Picked Nixon,” Boston Globe, June 14, 1960: 33.

18 Larry Claflin, “Slim Nixon Aims At Fat Hits,” Boston American, March 1, 1961: 26.

19 Ed Rumill, “Red Sox Expect Big Things of Nixon,” Christian Science Monitor, March 17, 1960: 14.

20 Larry Claflin, “Picture Dim for Sox,” Boston American, August 15, 1961: 5. The game in question was on July 19.

21 Bob Holbrook, “Sox Must Put Up Stars,” Boston Globe, December 2, 1963: 18.

22 Larry Claflin, “Morehead Sox ’64 — Nixon,” Boston Record American, January 15, 1964: 4.

23 Associated Press, “Sox Release Russ Nixon,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), March 31, 1970: 15.

24 Cincinnati Reds News Release, February 14, 1970.

25 Associated Press, “McNamara Fired; Reds Name Nixon,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 22, 1982: 56. An article on Nixon which offers his self-appraisal and acknowledges his credit to others, and his ambitions for the team is in the Atlanta Daily World, August 8, 1982: 7.

26 “Former Manager Nixon Not on the Reds’ Bandwagon,” unidentified newspaper clipping dated April 11, 1984 in Nixon’s Hall of Fame player file.

27 Glenda Nixon interview.

28 Ian MacDonald, “Nixon Leaves Expos, Joins Atlanta,” The Sporting News, October 28, 1985: 23.

29 Gerry Fraley, “Nixon Leaves Braves; Tanner Not Unhappy,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1987: 26.

30 Associated Press, “Nixon Glad to Be Managing Again,” Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock), May 14, 1988: 32.

31 Jerome Holtzman, “Braves’ New Manager Takes Aim At Tanner,” Chicago Tribune, May 24, 1988: C1.

32 Peter Pascarelli, “Nixon’s View of Braves Realistic, Not Rosy,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1988: 24.

33 Associated Press, “Braves Will Rehire Hixon for 1990,” New York Post, August 24, 1989.

34 Star News Services, “Nixon Fired, Is Annoyed with Braves,” Kansas City Star, June 23, 1990.

35 Associated Press, “Braves Fire Manager Nixon; Cox Is Named As Replacement,” Los Angeles Times, June 22, 1990: P10.

36 Guy Curtright, “Ex-Braves Manager Finds Satisfaction in Minor Leagues,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 29, 2005.

37 Bill Ballew, “Russ Nixon — Rookie-League Skipper Epitomizes A Baseball Lifer,” At the Yard, January 2006: 15.

38 Email from John Blake, December 21, 2017.

39 Glenda Nixon interview.

40 Ibid.

Full Name

Russell Eugene Nixon

Born

February 19, 1935 at Cleves, OH (USA)

Died

November 9, 2016 at Las Vegas, NV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.