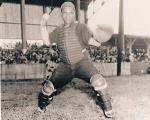

Sam Hairston

Patriarch of a three-generation big-league family, hard-hitting Negro Leaguer Sam Hairston played, coached, and scouted in pro baseball for over half a century. As a scout, Sam brought in at least five men who played for the Chicago White Sox, for whom he appeared briefly in 1951.

Patriarch of a three-generation big-league family, hard-hitting Negro Leaguer Sam Hairston played, coached, and scouted in pro baseball for over half a century. As a scout, Sam brought in at least five men who played for the Chicago White Sox, for whom he appeared briefly in 1951.

Two of Sam’s three sons signed pro contracts with the White Sox on their father’s recommendation. It might have been all three, but the Chicago Cubs drafted John Hairston in 1965. When Johnny made it to the Cubs for three games late in the 1969 season, the Hairstons became the first African-American father-son combo in the majors. In 1973, Jerry Hairston Sr. made his debut with the White Sox, bestowing a rare privilege upon his father. Sam Hairston is among the handful of big-league players who scouted a big-league son.1

The Hairstons made it a mini-dynasty when Jerry Jr. joined the Baltimore Orioles in September 1998. Sam died about ten months before Jerry Jr.’s debut, but he lived long enough to see the young man drafted, hit fungoes to him, and predict his future.2 When Jerry’s younger brother Scott broke in with the Arizona Diamondbacks in May 2004, he became the fifth of the clan to make The Show (a record for three-generation families).3 As former White Sox general manager Roland Hemond recalled in 2010, “Sam told me when Jerry Jr. and Scott were probably 10 and 8 that they would become major-league players. He was right.”4

The stamp of heredity is visible. In a Fox Sports interview from June 2009, Jerry Jr. pointed out “the Hairston nose” and “the Hairston walk” in a photo and rare video footage of his beloved grandfather.5 It was hardly surprising when he said of Sam in 2001, “He had a major influence on me.”6 Yet the depth of this family influence is truly remarkable. In 2010, Scott recounted a story from nearly eight years before, when he was playing in his second pro season at Class A. “It was after BP [batting practice] when this older guy, a scout, calls me over. He had to have been in his 70s. He said I reminded him of a player he had played against once. . .that player’s name, he said, was Sam Hairston.

“I told him he was my grandfather. He said, ‘That doesn’t surprise me. I didn’t even have to look at the roster. I saw the way you swing the bat. . .that’s what reminded me of him.’”7

Samuel Harding Hairston was born on January 20, 1920. Like many ballplayers, he shaved several years off his age during his playing career — and beyond. His obituary in the New York Times called it “a deception he and the [White Sox] continued to maintain with a wink during his 48 years with the organization. The White Sox 1997 media guide lists his birth date as 1925, although Mr. Hairston had long acknowledged he was really born in 1920.”8

Hairston’s place of birth has long been shown as Crawford, Mississippi. That is in Lowndes County, in the eastern part of the state, near the Alabama line. In May 2010, however, SABR member Glenn Lautzenhiser said that Sam may have been born in the Plum Grove community, several miles east. “We are trying to do additional research and get some kind of documentation,” he added.9

Sam was the second of 13 children born to Will and Clara Hairston (née Neal), who were married at ages 18 and 15, respectively. He had seven younger brothers (Johnny, Leotis, Herbert, Bob, Bill, Willie, and Jack) and five sisters (his older sibling Bessie, Sarah, Nellie, Leanna, and Gloria). He also had a half-brother named Earl from a prior relationship of Will’s. Jack Hairston, 24 years Sam’s junior, pitched one year of rookie ball in the White Sox chain in 1966. On the same squad was Sam Hairston Jr., who was born the year before his uncle.

In 1920, Crawford was a village of 323, and the population was still only 655 as of 2000. It’s not near any large cities. The state capital, Jackson, is about 115 miles southwest; Tuscaloosa and Birmingham, Alabama, are both closer. Tupelo, Elvis Presley’s birthplace, is roughly 70 miles north — but at least two other famous Americans have roots in Crawford. Delta bluesman Big Joe Williams was born there and star NFL receiver Jerry Rice was raised there.

The Hairston family moved from Lowndes County to the Birmingham area in 1922, as Jerry Hairston Sr. recalled in 2010. Will was no doubt seeking better employment. He became a coal miner, as did Garnett Bankhead, the father of the five “Bankhead Boys” who also grew up in Birmingham and played in the Negro Leagues. Alabama’s coal country fueled Birmingham’s steel industry. Mining was a hard and dangerous job — but it was a step up from sharecropping in the Jim Crow South.

Sam Hairston “spent his formative years in Hooper City, Ala., which is located a long fly ball outside Birmingham.”10 As he recalled in a 1995 interview, he was also raised in North Birmingham and Sayreton (another Birmingham suburb). The 1930 census shows the family — there were seven children at that point — living in Sayreton. Sam quit school at an early age and helped his brothers and sisters to attend instead.

Sam grew up playing baseball in open fields and lots. “When he was 16, he lied about his age, saying he was 18, to get a job and the opportunity to play baseball in the local industrial league.”11 He joined the American Cast Iron Pipe Company (ACIPCO), which was also his father’s employer; the 1930 census records Will’s job then as laborer in a pipe shop. Sam played for the ACIPCO company team, which the online Encyclopedia of Alabama called the “powerhouse of all the industrial teams.” His teammates included Piper Davis and Artie Wilson, two other future members of the local Negro League team, the Birmingham Black Barons.12

Hairston did not serve in the military during World War II. Although ACIPCO was engaged in war work (manufacturing steel parts for ships, planes, and tanks), that was not the main reason — Sam was 4F. Jerry Hairston Sr. remembered, “He went through all the physicals, clear up to the podiatrist. There was something wrong with his big toe, a foul tip had broken it. The doc was a big baseball fan, and that was it — he rejected him right there.”

Hairston did not serve in the military during World War II. Although ACIPCO was engaged in war work (manufacturing steel parts for ships, planes, and tanks), that was not the main reason — Sam was 4F. Jerry Hairston Sr. remembered, “He went through all the physicals, clear up to the podiatrist. There was something wrong with his big toe, a foul tip had broken it. The doc was a big baseball fan, and that was it — he rejected him right there.”

In 1944, Hairston joined the Black Barons. He was a third baseman by trade, and one account held that he volunteered to back up starting catcher Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe after “Duty” broke a finger.13 Jerry Hairston Sr. heard a different version from Radcliffe himself, though. “The third baseman [Johnny Britton] was holding out for more money, and Double Duty, who knew what was going on in the front office, knew that [Britton] had just come to terms with the team. He asked my father, ‘Can you catch?’ And when Sam said yes, he said, ‘You can catch tomorrow. I’m going to be sick.’”

The following year, the Barons traded Sam to the Cincinnati-Indianapolis Clowns for Pepper Bassett. He spent the next six seasons with the Clowns, mainly as a catcher. He split time with Buster Haywood behind the plate, also playing first base and third base, with occasional appearances in the outfield.

Sam matured into a solid .300 hitter — and then some. He made excellent contact and was very hard to strike out. Although he was not known for home-run power, he hit a lot of doubles and (in his younger days) ran well enough to get a good number of triples too. As a catcher, “these are the stories that I heard coming up in the minors,” said Jerry Hairston Sr. “He blocked the ball well, he didn’t have a rifle arm, but he had a quick release and was very accurate.

“He handled pitchers well too. Glen Rosenbaum, who became the traveling secretary for the White Sox, was a minor-league pitcher. He told me he had one of his best years with my father catching him. [Sam] said, ‘Just pitch what I put down,’ and Glen said, ‘I didn’t shake him off once the whole year.’” Rosenbaum was 13-4 for Charleston in 1959.

Hairston had an extensive career in winter ball. The first evidence of this action comes from 1946, when he played in the California Winter League, the first integrated pro circuit in the United States. Sam was with a team called the Kansas City Royals, which featured the great pitcher Satchel Paige.14 The following winter Sam joined the San Juan Senadores in the Puerto Rican Winter League, where many top-notch Negro Leaguers of the day were starring. His journeys through Latin America would later take him to Venezuela, Mexico, and Panama. “I don’t know if he was fluent in Spanish, but he knew a lot more than I did,” said Jerry Sr., who played in Mexico and married a woman he met there. “He’d understand exactly what people were talking about.”

In 1948 Sam became a Negro League All-Star. He did not appear in the first of that year’s two East-West All-Star Games at old Comiskey Park in Chicago, but he did pinch-hit in the second at Yankee Stadium.

Hairston returned to San Juan in the winter of 1948-49. It appeared that he would do the same in 1949-50, for a baseball card of him in Puerto Rico’s “Toleteros” series was issued. Instead, however, he joined the Vargas Sabios (Wise Men) in the Venezuelan League. There’s a strong possibility that Sam made this connection thanks to Sam Bankhead, who had previously managed Vargas. “They were good friends,” said Jerry Sr.

Sam won the Triple Crown for the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro American League (NAL) in 1950 with a .424 batting average, 17 homers, and 71 RBIs in 70 games. Even though the caliber of Negro League ball had declined markedly by then, the performance was still impressive enough for the White Sox to sign him on July 31. The NAL season still had another month or so to run (with a badly unbalanced schedule), but Sam’s sizable lead in all three categories endured.

Two days before Sam signed, the Chicago Defender reported that he was the leading vote-getter for the 1950 East-West classic.15 Running second was Elston Howard, then an outfielder. Since both men had joined big-league organizations, though, they were ineligible to play in black baseball’s national showcase that August. Perhaps Sam’s early departure also explains why Jesse Douglas was named the NAL’s most valuable player that November.16

The scout who signed Hairston was John Wesley Donaldson, the former star pitcher who became the first African-American to join a big-league scouting staff when the White Sox hired him in June 1949. That summer, Donaldson also signed first baseman Bob “The Rope” Boyd from the Memphis Red Sox. As Boyd recalled in the SABR biography by Bob Rives, Donaldson rode the Red Sox bus with the club.

Hairston and Boyd finished the 1950 season with Colorado Springs in the Western League. Sam then returned to Venezuela and the Vargas club. He had an excellent season, hitting .375 — including a 26-game hitting streak, then a league record. He was named league MVP. Since the Sabios were still in the race in February 1951, Sam wrote White Sox general manager Frank Lane “a piteous letter” saying that he couldn’t bear to leave. He reported late to spring training.17

In 1997 Sam told the Chicago Tribune about that camp. “It wasn’t a problem. The guys were nice. [Manager] Paul Richards wasn’t too friendly. But he wasn’t friendly to anybody.”18 Hairston and Boyd received a fair amount of press coverage during camp, but they were assigned to Triple-A Sacramento. In fairness, though, first baseman Eddie Robinson had his career year in 1951 and Phil Masi was still a capable veteran catcher. Meanwhile, the White Sox obtained Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso in a three-way deal at the end of April, and the Cuban became their first player of African descent to appear in a regular-season game.

The big club gave Sam his shot that July after backup catcher Gus Niarhos suffered a broken wrist on a foul tip. Phil Masi had also been suffering knee problems. Hairston remained on the roster for about five weeks, appearing in just four games between July 21 and August 26. A couple of days after Sam’s debut, the White Sox obtained catcher Bud Sheely (who had also played in the California Winter League in 1946). They swapped another backstop, Joe Erautt, to Seattle of the Pacific Coast League. There may have been some cronyism involved. Bud’s father, Earl Sheely, was a former White Sox player of the 1920s who had become general manager of the Rainiers. The teams made many deals in those years.

As a result, Hairston pinch-hit three times, appearing twice behind the plate with just one start. He was 2-for-5 with an RBI double, plus two walks. When Niarhos returned to action in early September, Sam was sent out. In November 1951, the White Sox acquired Sherm Lollar, who would become their primary catcher for the next decade.

1n 1993 Sam said that an accident was responsible for his demotion. “We were practicing one day, and I was hitting ground balls to (veteran infielder) Floyd Baker. I hit one that bounced up and hit him right in the mouth. That was the end of my major-league career. Floyd was hurt, and they sent me away for good.”19

Sam played nine more summers in the minors after that, all in the White Sox chain except for a portion of 1958, when he was in the Baltimore organization. Most of that time was spent at Class A, except for the 1954, 1957, and 1958 seasons. He might also have been at Triple-A in 1956, as the Toronto Maple Leafs purchased him in October 1955. The following April, though, Chicago sent Carl Sawatski to Toronto and reassigned the veteran to Colorado Springs.

Hairston remained a very effective line-drive hitter, batting .304 lifetime in the minors with 53 homers. He was well over .300 in the four additional seasons he played for Colorado Springs (1952-53; 1955-56), including a league-leading .350 in 1955. Probably his finest year with the Sky Sox was 1953, though, when he was named Western League MVP. Sam was hugely popular in Colorado Springs, earning the nickname “The Man” for his toughness and leadership on the field and in the community. The city held a night for him on July 31, 1955, giving him a new Pontiac car.

Hairston also continued to play winter ball. After his third season in Venezuela (1951-52), he went to Mexico’s Liga del Costa del Pacífico. He made the league’s All-Star team, representing the Southern Division, in both 1952-53 and 1953-54. In the latter season, with the Jalisco Charros, he hit .306 and led the league with 58 RBIs. Sam also played for the Obregón Yaquis in 1955-56. Moving to La Liga Invernal Veracruzana in the 1956-57 season, he hit .362 for the Puebla Pericos, second in the league. In the winter of 1957-58, Hairston returned to Venezuela. He played for Rapinos in the nation’s Occidental League. The White Sox sent several of their players there; in fact, their star shortstop Luis Aparicio (a Venezuelan native) was the club’s part-owner.20

In May 1960 Sam retired as an active player to scout the Alabama area for the White Sox. The Sporting News noted in its June 1 issue that his first signing was shaping up to be his own son. Although the younger Hairston was not mentioned by name, it was most likely John, who starred at Birmingham’s Hooper High. Johnny decided instead to attend Southern University in Louisiana, a historically black institution with a good baseball program. Another Negro League legend was watching: Buck O’Neil, who covered the same Deep South turf for the Cubs. A knee injury shortened John’s career, but his sons John Jr. and Jason reached Class A in the 1980s and ’90s. They were the sixth and seventh of nine Hairstons to play pro ball.

Sam was scouting unofficially several years before he quit playing. Jerry Hairston Sr. said, “He recommended Lee Maye to the White Sox, but they didn’t sign him.” Arthur Lee Maye, a Tuscaloosa native, signed with the Milwaukee Braves in 1954. In 1961 the White Sox also passed on Lee Andrew May, who signed with Cincinnati and went on to hit 354 big-league homers. The White Sox drafted Carlos May in the first round of the 1966 draft; according to Jerry Sr., Sam said, “You missed his older brother [Lee], you better not miss this one!”

In its June 1967 issue, Ebony magazine noted that Hairston was one of eight full-time black scouts in the majors. In addition to him and Buck O’Neil, the others were Charles Gault (also of the White Sox), Quincy Trouppe and David “Showboat” Thomas (Cardinals), Hiram “Jack” Braithwaite (Senators), Alex Pómpez (Giants), and Bob Thurman (Reds). Sam worked closely with Walt Widmayer, another veteran scout based in Florida.

Other major leaguers Hairston turned up for the White Sox were Lee “Bee Bee” Richard, Lamar Johnson, and Reggie Patterson. He also recommended the team’s first-round pick in the June 1969 draft, Ted Nicholson (who never made it out of Class A). Roland Hemond remembered that Sam was also high on pitcher Jimmy Key, who grew up in Huntsville, Alabama. The lefty was another one who got away from the White Sox, though, as the Toronto Blue Jays drafted him out of Clemson in 1982. Although SABR’s Scouts Committee shows Hairston’s scouting career running through 1982, a number of reports after that showed him as still active in that role. The latest was the August 1992 issue of Ebony.

Sam also coached in the White Sox farm system. He helped instruct rookies at the club’s minor-league spring training in Sarasota for 21 years, mainly in the 1960s and ’70s, although one report showed him on the scene in 1991. Roland Hemond said, “Sam would work very long hours on the field to help young players. He spent long days feeding balls into the pitching machines, always smiling and never complaining.” He was also valuable as the only Spanish-speaking coach in the organization at that time. Sam was an interpreter for young Latino players like Mexican-born Jorge Orta. Orta, whose father, Pedro, was a star player in Cuba and Mexico, had Jerry Sr. as his first roommate in America. In the late 1980s, Sam took the young Venezuelan pitcher Wilson Álvarez into his Birmingham home.21

Sam returned to the Mexican winter league as a coach with the Hermosillo Naranjeros in 1975. Son Jerry was there too. The previous year, Jerry told the Sarasota Journal that as a youth in Birmingham, his father would pitch to him in the back yard, using champagne corks and bottle caps as training devices. “He could make them slide, curve, anything.” He added, “Every day my dad was at home it was all baseball. We talked baseball. We ate it. We drank it.”22 Jerry Hairston Jr. and Scott Hairston also eagerly soaked up all the tales that their grandfather could offer, as well as the same instruction. Jerry Jr. remembered that Sam served up little balls of tape-wrapped newspaper that would really move, saying, “If you can hit these, you can hit anything!”23

According to Jerry Sr., when the Comiskey family planned to sell the White Sox, orders were given to the farm director at the time to make sure Sam Hairston always had a job with the team.24 Possibly the organization viewed him as more valuable working with its young prospects, but one still wonders why Sam did little coaching at the big-league level. He eventually did get a chance, though. As Roland Hemond recalled, “[Owner] Bill Veeck saw to it that Sam was hired as the White Sox bullpen coach in 1978. It was at one of the spring trainings that it was discovered during routine physicals that he was diabetic, and I think he had to forgo his coaching duties. However, he continued to scout for the Sox.”

It appears that Hairston was on the Chisox staff for just that one season. When Larry Doby took over for Bob Lemon as manager in July 1978, he retained Sam.25 After Don Kessinger succeeded Doby that October, though, the White Sox operated with fewer coaches in 1979. Along with Sam’s health, Veeck’s shoestring budget may also have been a factor. Kessinger was a playing manager until he resigned, and until pitching coach Freddie Martin died that June, Ron Schueler served as Martin’s assistant while pitching sporadically in his last season. “We had no money for another coach,” Kessinger said in 1997.26

For the last 12 years of his life, Sam was on the staff of the Birmingham Barons in the Double-A Southern League. A 1994 article in the Rocky Mountain News showed him as a part-timer — but he was quite active. “Nobody out there’s even half my age,” crowed Sam, then 74. “Not even the other coaches.”27 That was also the year NBA superstar Michael Jordan gave baseball a whirl. He was assigned to the Barons; “I’m sure Dad tried to help him in some form,” said Jerry Sr.

Shortly after the 1997 season ended, Hairston died from pulmonary cardiac arrest at a Birmingham nursing home. He was survived by his second wife, Dora (whom he had met in Hermosillo) as well as John, Jerry, and Sam Jr., plus ten grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Sam’s sons were born to his first wife, Jessie Merritt (they were divorced in 1976). As of September 2010, Jessie was still with us.

When he heard that Sam had passed, White Sox co-owner Jerry Reinsdorf issued warm praise. “Sam Hairston will be missed, not just by everybody in the White Sox organization, but by everyone associated with the game of baseball. In addition to being a tremendous ballplayer with a wealth of experience and knowledge about the game, Sam was a great person. He left a lasting impression on everyone he met over his 53 seasons in the game.”28

“Sam is one of the finest people I have known in baseball,” Roland Hemond said in 2010. Yet as likable and popular as Hairston was, he was also realistic. In 1995 he said, “You have to conduct yourself as a gentleman in order to go this far. . .The White Sox didn’t keep me there because they loved me. They kept me there because I did a job.”

In 1999, Jerry Hairston Sr. said that his father was “born too soon” and that he didn’t get “a fair shake.”29 Even so, two years later Jerry Jr. said, “My grandfather should’ve received a lot more things in his life, but he was never bitter. He had nothing but great things to say about the great game of baseball.”30

Hairston had received some honors during his lifetime. Colorado Springs held a day in his name in 1993, 40 years after his MVP season in the Western League. Birmingham also staged a special day in 1996 and named a sports complex for him. Yet the big gala came almost 13 years after Sam’s passing — from October 13 to 16, 2010, Columbus, Mississippi devoted a full three days to the Sam Hairston Celebration. Previously, in 2008, the seat of Lowndes County had honored another of its native sons who made a name in the world of sports: the great broadcaster Red Barber. A marker was dedicated to Sam at the site of the ballpark, then still under construction, to be named for him.

The Hairstons already have a special legacy in baseball — but down the road, there might just be a fourth generation. “That love of the game is a part of our family,” said Jerry Jr. in 2009. “We really feel [it] is unmatched. Seeing my son and my nephews, Scott’s boys, seeing the love they have for the game. . .My grandfather would definitely be proud of that.”31

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Jerry Hairston Sr. for his memories (telephone interview, September 18, 2010). Thanks also to SABR members Glenn Lautzenhiser, Roland Hemond, Larry Lester, and David Raith; Jonathan Nelson (general manager) and Justin Rosenberg (media relations) of the Birmingham Barons; Eric Costello.

Sources

On June 16, 1995, Ben Cook interviewed Sam Hairston for the Birmingham Black Barons Oral History collection. The audio files are online in the Birmingham Public Library’s Digital Collections:

Part 1: http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/p15099coll2&CISOPTR=6&CISOBOX=1&REC=16

Part 2: http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/p15099coll2&CISOPTR=4&CISOBOX=1&REC=1

1920 and 1930 census records

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994: 346.

Sortillón Valenzuela, Manuel de Jesús. Online history of Mexico’s Liga de la Costa del Pacífico: www.historiadehermosillo.com/BASEBALL/Menuff.htm

Venezuelan statistics: http://www.planeta-beisbol.com/lvbp/

www.encyclopediaofalabama.org

Notes

1 Two other known examples are Joe Stephenson (who signed his son Jerry) and Lew Krausse Sr. (who signed Lew Jr.). There may be others.

2 Rosenthal, Ken. “Hairston Jr. puts finishing touch on photo.” Baltimore Sun, July 11, 1999. Mandel, Ken. “Hair-raising Legacy.” mlb.com website, unknown date, 2001. (http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/mlb_negro_leagues_story.jsp?story=hairstonstory)

3 Two three-generation families have had four apiece: the Boones and the Bells. The Colemans have had three.

4 The brothers were actually born four years apart.

5 “Hairston proud of family history.” Fox Sports video interview, June 28, 2009 (http://multimedia.foxsports.com/m/video/23552345/hairston-proud-of-family-history.htm)

6 Mandel, op. cit.

7 Brock, Corey. “Family roots keep Hairstons grounded.” mlb.com website, March 3, 2010 (http://mlb.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20100303&content_id=8658066&vkey=news_mlb&fext=.jsp&c_id=mlb)

8 Thomas, Robert McG. “Sam Hairston, 77, First American Black on White Sox, Dies.” New York Times, November 9, 1997.

9 Baswell, Allen. “Plans under way for Columbus tribute to local Negro League player.” Columbus (Mississippi) Dispatch, May 5, 2010.

10 Brock, op. cit.

11 Ibid.

12 Putnam, Seth. “A legacy on the diamond: Columbus to honor ballplayer Sam Hairston.” Columbus (Mississippi) Dispatch, June 16, 2010. Powell, Larry. Black Barons of Birmingham. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2009): 180.

13 Ibid., loc. cit.

14 McNeil, William. The California Winter League. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2002): 228.

15 “Sammy Hairston Grabs Lead In East-West Poll.” Chicago Defender, July 29, 1950: 17.

16 Russ J. Cowans, “Jesse Douglas Picked As Most Valuable In The NAL”, Chicago Defender, November 11, 1950: 17

17 Munzel, Edgar. “Negro First Sacker Gets Chance to Win Berth on White Sox.” The Sporting News, February 21, 1951: 10.

18 Vanderberg, Bob. “Though Late, First In Their Fields In Chicago.” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1997.

19 Ralph Routon, “Sky Sox bring Hairston back for a curtain call.” Colorado Springs Gazette, August 20, 1993: C4.

20 “Aparacio Part Owner of Rapinos.” The Sporting News, October 9, 1957: 33.

21 Merkin, Scott. “Hairston earned great respect.” mlb.com website, February 18, 2005.

22 Lassila, Alan. “Hairston Uses Chisox ‘Insult’ as Incentive.” Sarasota Journal, March 4, 1974: 1D. Other stories mention Sam throwing tape-wrapped fishing corks.

23 “Hairston proud of family history”

24 Merkin, op. cit. Dorothy Comiskey Rigney sold her 54% stake to Bill Veeck in March 1959; Charles Albert Comiskey II sold his stock in December 1961.

25 “Sox fire Bob Lemon, name Doby.” Chicago Tribune, July 1, 1978.

26 Macht, Norman. “Don Kessinger Looks Back on His Big League Career.” Baseball Digest, November 1997: 80. Tony La Russa, who succeeded Kessinger, expanded the staff again, hiring Art Kusnyer as bullpen coach in November 1979.

27 “Barons’ Seventy-Something Coach an Inspiration to Kids.” Rocky Mountain News, July 19, 1994.

28 Associated Press, November 7, 1997.

29 Rosenthal, op. cit.

30 Mandel, op. cit.

31 “Hairston proud of family history”

Full Name

Samuel Harding Hairston

Born

January 20, 1920 at Crawford, MS (USA)

Died

October 31, 1997 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.