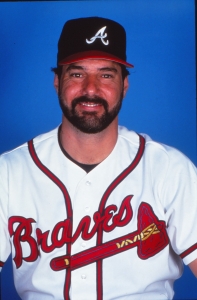

Steve Bedrosian

Bedrock (n): Unbroken solid rock; any firm foundation.1

Bedrock (n): Unbroken solid rock; any firm foundation.1

That dictionary definition explains why “Bedrock” was an apt nickname for Steve Bedrosian. In his prime, he was a rock-solid relief pitcher and the foundation on which his teams built a bullpen.

Stephen Wayne Bedrosian was born in Methuen, Massachusetts, on December 6, 1957, to Michael (a materials and inventory specialist for Western Electric) and Jean Bedrosian (office manager for W.T. Grant Company)2 and is one of a handful of major leaguers of Armenian descent. He played baseball and soccer and wrestled for the Methuen High School Rangers, where his performance would (24 years later) earn him recognition by the North Andover Eagle-Tribune as the area’s “Top Athlete of the 20th Century.”3 After graduation in 1975, he played baseball for the Knights of Northern Essex Community College in nearby Haverhill, Massachusetts, for two years before enrolling at the University of New Haven. In his only season there, he compiled a 13-3 record and three saves, helping Coach Frank “Porky” Viera’s 1978 Chargers to a third-place finish in the Division II College World Series.4 He was named to the Division II All-America First Team by ABCA/Rawlings and to The Sporting News’ All-American Second Team.5 He was one of only three Division II players (and the only pitcher) to be so recognized by The Sporting News.

Those All-American honors came on the heels of being selected by the Atlanta Braves in the third round of the 1978 amateur draft. He was the Braves’ third pick — after future Atlanta teammates Bob Horner and Matt Sinatro — and the 53rd overall pick. He quickly signed with the Braves and was assigned to the Kingsport (Tennessee) Braves of the Appalachian (Rookie) League. After starting six games and compiling a 2-2 record and a 3.08 ERA, Bedrosian was promoted to the Class-A Greenwood (South Carolina) Braves, for whom he started eight games, went 5-1, and lowered his ERA to 2.13.

Bedrosian progressed steadily upward through the Braves farm system. He spent the next two seasons as a starter for the Savannah (Georgia) Braves in the Double-A Southern League. Although one reporter dubbed him perhaps the hardest thrower in the league, Bedrosian himself said it was “the first league I’ve been in where I can’t just reach back and blow it by everyone.”6 He added: “I don’t have a curve or a change-up. I’m going to have to learn them if I’m going to move up.”7 In 1980 he was a Southern League All-Star8 and the workhorse of the Savannah staff, pitching 203 innings and completing nine of his 29 starts for a 14-10 record. That performance earned him a spot on Atlanta’s 40-man roster.9 After a season of winter baseball in the Dominican Republic,10 Bedrosian joined the Richmond (Virginia) Braves in the Triple-A International League, where he started 25 games and made his first relief appearance. He had a 10-10 record and a 2.69 ERA when he was called up to Atlanta.

Bedrosian made his major-league debut on August 14, 1981, at Dodger Stadium. He relieved John Montefusco in the fourth inning with one out and the bases loaded after the Dodgers had scored two runs to break a scoreless tie. Bill Russell, the first batter Bedrosian faced, drove in a run with a sacrifice fly. Bedrosian then hit opposing pitcher Dave Goltz but got Davy Lopes to pop out to end the inning. He was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the inning, but he was in the big leagues to stay. He earned his first major-league victory the following night when he struck out two of the three Dodgers, he faced in the fifth inning to preserve a 1-1 tie before being removed for a pinch-hitter in the sixth, when the Braves scored an unearned run to take a lead they never relinquished.

One night later, the Dodgers avenged that loss with a 6-5 win, and Bedrosian was charged with the loss. He entered the game to start the seventh inning with the Braves leading 5-3 and walked two batters before yielding a two-out, two-RBI double to Steve Garvey and being replaced on the mound by Gene Garber, who allowed a RBI single that put the Dodgers ahead by the final score of 6-5.

Bedrosian’s next appearance was on August 22 at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, when he made his home debut in his first major-league start in the first game of a doubleheader against the Montreal Expos. After five innings, he had yielded two hits and three walks, and the Braves led 3-0. He did not retire a batter in the sixth inning. He gave up an unearned run followed by John Milner’s three-run homer and left the game trailing 4-3 with two runners aboard. One of those runners scored another unearned run, and when the Braves could muster only one more run, Bedrosian was charged with his second loss. After four games, his record was 1-2. He appeared in 11 more games (17 innings) in relief without another decision or another save opportunity and ended the 1981 season with an ERA of 4.44 — his highest until his final season. In December Bedrosian became the first Brave who did not have a long-term contract to agree to terms for the 1982 season ($37,000) and was dubbed one of the club’s young pitchers “most difficult to pry away from the Braves.”11

Bedrosian returned to the Dominican Republic for another season of winter baseball and was pitching well for the Estrellas12 of San Pedro de Macoris (2.83 ERA) when he suffered minor injuries in an auto accident. At the time, he was called “one of the best pitching prospects since the Braves moved to Atlanta”13 and one of eight candidates to join the Braves’ starting rotation.14 In March he exacerbated his injury-plagued offseason by breaking his finger. Fortunately for the lanky (6-feet-3, 200 pounds) right-hander, it was on his left hand. A month later, he was one of seven rookies on Atlanta’s Opening Day roster.15 He had arrived with two nicknames — Bedrock (the one that lasted throughout his career) and Mr. Smoke (later Kid Smoke)16 — that attested to his two primary characteristics as a baseball player: a “fierce competitor” who “throws hard.”17

The Braves got off to a record-breaking start in 1982, winning their first 13 games. Bedrosian was the starter on April 10 against Houston in the 3-0 Braves’ second home game. The Braves staked him to an early 5-0 lead, but he gave up a walk and a two-run homer in the third inning and two more hits and a walk in the fourth before being lifted. Six days later, in Houston, he pitched three shutout innings to protect a 5-3 lead as the Braves improved to 9-0. Back in Atlanta on April 20, he relieved Tommy Boggs with two out in the second inning. The bases were loaded, and the Reds had a 2-0 lead. Bedrock got a quick out and followed with four more scoreless innings. When he left the game, the Braves led 4-2, and that was the final score, so Bedrosian was credited with the win in the game that gave “Hotlanta’s Hotbraves”18 their record-breaking 12th consecutive victory to start a season. The team increased that record to 13 straight wins (which was tied five years later by the AL Milwaukee Brewers). Bedrosian’s fondest memory of that streak came at its end. After the Braves finally lost in Game 14, a fan displayed a sign that said: “161-1 Isn’t Bad!”19

For the rest of that season, Bedrosian was used mainly in relief and did an “awesome” job.20 Through July 27, his 1.46 ERA was the best on the team, and he had a 5-1 record and six saves in 34 games and was averaging 7.3 strikeouts per nine innings. He was deemed “among the hardest throwers ever to pitch for the Atlanta Braves.” He acknowledged that he had loved striking batters out since his days in Little League and admitted that he didn’t “try to nick corners.”21 Braves pitching coach Bob Gibson explained that Bedrosian was better suited for his relief role because starting gave him “too much time to think.”22

Although he cooled off a bit in the latter part of the season, Bedrosian ended his first full season with a record of 8-6, 11 saves (in 17 opportunities), a 2.42 ERA, and 123 strikeouts (more than any other NL relief pitcher) in 64 games (only three starts). He did not fare well in the National League Championship Series when the Cardinals swept the Braves and went on to win the World Series. In Game One, Bedrosian replaced Pascual Perez in the sixth inning with no outs, the Braves down 2-0 and two runners aboard. He gave up a walk and three hits, allowing both inherited runners to score, and gave up two added runs, increasing the Cardinals lead to 6-0, while recording only two outs. He was also one of six pitchers the Braves used in the decisive Game Three, facing one batter (Keith Hernandez) and striking him out with the bases loaded in the eighth inning.

Postseason awards are based only on regular-season performance, and Bedrosian was named the National League Rookie Pitcher of the Year by The Sporting News. Pitching coach Gibson obviously had seen something others had missed; Steve Bedrosian, who had been a starter throughout his minor-league career (81 starts in 82 games), was now a reliever, and the Braves believed that their bullpen was set for 1983 with him paired with Gene Garber.23 That duo plus Rick Camp, who contributed five saves, had been recognized by Rolaids as the “top team bullpen” in the majors.24

The Braves showed their confidence in Bedrosian with a pay raise from $37,000 to $155,000 — the highest percentage increase on the team25 — and he became the team’s closer, finishing 52 of his 69 relief appearances. Bedrosian’s work had him leading the race for the Rolaids Relief Pitcher Award in early August, but he struggled during the latter part of the season as his ERA rose from 3.00 to 3.74. At least one observer thought that these struggles were the result of his having been “shamefully overworked”26 while Gene Garber was on the disabled list in July. His lone start that year came in the Braves’ next-to-last game, on October 1 against the Padres in San Diego. He pitched seven strong innings and left the game in the eighth inning with a 2-1 lead, but lost the win when two relievers gave up two runs and the Braves then lost in the 10th. That game, his final appearance for the season, lowered his ERA to 3.60 but did not allow him to even his 9-10 record to .500. He did increase his strikeout rate to almost one per inning and his strikeout/walk ratio to 2.24, and recorded 19 saves (in 27 opportunities).

Early in 1984, there was some speculation that Bedrosian might move into the Braves’ starting rotation because Phil Niekro had been released and Pascual Perez had been arrested in the Dominican Republic.27 However, when the season started, Perez was a regular starter, and bullpen duties were distributed among Gene Garber (62 relief appearances/11 saves/42 closures), Donnie Moore (47/16/29), Jeff Dedmon (54/4/19), and Bedrosian (36/11/28).

Bedrosian got off to a fabulous start. By June 6, he had pitched 33⅓ innings in 19 games and had a 4-1 record plus eight saves with an ERA of 0.54. Then he struggled through a steak of four consecutive losses over an eight-day period in which he blew two ninth-inning leads on the road, gave up a 12th-inning walk-off single after walking the only other two batters he faced, and yielded back-to-back doubles to the first hitters he faced in the eighth inning of a tied home game. His ERA had tripled to 1.73. Those two blown-save opportunities were Bedrosian’s first and last of the season; his overall success rate (84.8 percent) led the team.

Bedrosian was the only member of the bullpen quartet who logged any starting assignments. While his record in four starts was 3-1, he needed and received lots of run support (4.8 runs per game compared with the team’s season average of 3.9); his ERA in those games was 3.86 (vs. 1.71 in his relief efforts). His overall ERA (2.37) was still lowest on the team among those who pitched in more than three games.

Bedrosian’s fourth start, on August 15, was his last game of the 1984 season. The Braves had planned to move him into Craig McMurtry’s slot in the rotation, but he was experiencing some pain in his right bicep that required attention and caution.28 While his season ended early, there was much to be celebrated. He had improved his ERA, his winning percentage (9-6/.600), and his strikeout rate while lowering his WHIP to 1.171 (1.138 in relief). Talk of moving him into the starting rotation continued into the offseason.29

This time the talk resulted in a change. In 1985, the Braves had a new manager (Eddie Haas) and a new pitching coach (Johnny Sain). With Bruce Sutter now available as closer, Bedrock joined the starting rotation30 — for the first and only time in his major-league career. It was a less than stellar experience. He started 37 games (second only to Rick Mahler) and finished none of them — a record for most unfinished starts in a season.31 He had the same number of losses (15) as Mahler, but 10 fewer wins (seven). Yet, compared to the rest of the starters, none of whom posted a winning record, his performance was admirable. His 3.83 ERA was second only to Mahler’s, and his 5.8 strikeouts per nine innings led all starters. Not bad for a season when he pitched more innings than in his previous two seasons combined and was “supported” by a team that ranked 10th in the National League in runs scored (3.9 per game) and ninth in fielding percentage (.976), committing more errors (159) than all but one other team.

Yet, on December 10, 1985, the Braves traded Bedrosian and outfielder Milt Thompson to Philadelphia for catcher Ozzie Virgil and young pitcher Pete Smith. New general manager Bobby Cox wanted Virgil’s power to “restore thunder”32 to the Braves’ anemic offense and risked giving up Bedrosian only after the Phillies turned down his offer of Jeff Dedmon. Phillies president Bill Giles made it clear that Bedrosian was the “plum” in the deal, seeing him as “the main short reliever in a really deep bullpen.”33

After working his way through a sore arm during spring training,34 Bedrosian started the 1986 season with his new team still trying to transition back into a reliever’s role after a full year as a starter, and he struggled for a while.35 He won in his Phillies debut, but it wasn’t easy. He entered a 1-1 game in the top of the 10th in Cincinnati and got three quick outs. The Phillies scored four times in the 11th, but Bedrosian gave up two runs in the bottom of that inning before retiring a batter. The Reds had the tying runs on base before he struck out two batters to preserve the 5-3 win. His home debut was less stressful; he threw a 1-2-3 inning as the fifth of eight Philadelphia pitchers in a 9-8 win over the Mets. In his next game, he again took the mound in the 10th inning of a 1-1 tie, gave up two runs to the Pirates, and was the losing pitcher when the Phillies failed to rally.

By the end of April, Bedrosian had appeared in eight games, and his record was still 1-1. He ended the month with his first three saves, but gave up runs in two of them. His ERA was 7.27, and he had become a favorite target of the Phillies’ notoriously noisy boo-birds.36 The turnaround began in May with three solid relief appearances, and really took hold (perhaps appropriately) in Atlanta, when he earned a save on May 9 and a win two days later. Bedrosian gave Phillies pitching coach Claude Osteen credit for his improved mechanics.37

Bedrosian continued to improve and eventually earned the respect of those finicky fans, and the trade that brought him to Philadelphia was being praised as one of the best of the year as Bedrock gave the Phillies “the best right-handed relief in years.”38 His fastball was consistently timed at 95 mph and he was having one of the best seasons of any NL reliever.39 He finished the season with 29 saves, tying the Phillies’ team record. His ERA (3.39) and home-run rate (1.2 per 9 innings) were higher than in his last year as a Braves reliever, but his won-lost record (8-6) and walk and strikeout rates were remarkably similar to that year. He was back at home in the bullpen.

The reward was a two-year contract worth $1.75 million, ensuring that he would not become a free agent after the 1987 season, and Bedrosian declared himself to be “much more relaxed and ready to pitch well from the start.”40 Others expected him to be the anchor of the Philadelphia bullpen.41 That optimism seemed unwarranted and certainly premature as Bedrock got off to another rocky start. In his first six games, he allowed 10 runs on 11 hits (including four home runs) and had an ERA of 11.05. Remarkably, he also had been credited with two victories and almost became the NL’s first three-game winner on April 18 in the final game of that stretch. After Bedrosian gave up four runs to the Pirates in the eighth inning to blow a three-run lead, Mike Schmidt put the Phils ahead in the top of the ninth with his 500th career home run. The official scorer awarded the victory to Kent Tekulve, who shut down the Pirates in the bottom of that frame.

On April 26, in his eighth appearance, Bedrosian recorded his first save of the season, at home against the Pirates. On May 10 he started a streak in which he earned 19 saves in 20 appearances including a then-major-league record of 13 consecutive saves. He explained his success by saying, “I’m not aiming or trying to hit the corners. I’m just reaching back and letting it fly.”42 By the All-Star break, he had 24 saves and three wins for a team with only 42 victories, and he was named to the All-Star team for the first (and only) time in his career. In that game, he played a pivotal role with a fielding play that made him a hero instead of a potential “goat.” He entered a scoreless game in the bottom of the ninth and sandwiched two walks around a successful sacrifice bunt, putting the potential winning run on second base. He then induced a grounder to first baseman Keith Hernandez, who threw to second for the force out. Hubie Brooks’ return throw to Bedrosian, who was covering first, was wild and it looked as though the winning run would score, but he dove and snagged the errant throw, scrambled to his feet, and threw home where Ozzie Virgil (!) applied the tag that completed the double play and ended the inning.43 The NL eventually won the game 2-0 in 13 innings.

Following his All-Star Game heroics, Bedrock continued to be rock-solid in relief. He eclipsed his previous season high in saves with his 30th on July 31 — the quickest in history to reach that milestone44 — and ended the season with a league-leading 40 saves, becoming the first Phillies pitcher to lead the league in that category since the save was adopted in 1969. That magical season was capped off when the BBWAA gave Bedrosian the Cy Young Award in the closest vote in the history of the award. Bedrosian (5-3; 2.83 ERA) edged Cubs starter Rick Sutcliffe (18-10; 3.68 ERA) by two points and Rick Reuschel (13-9; 3.09 ERA), who divided the season between the Giants and the Pirates, by three. Eight pitchers received votes, and no pitcher was named on all 24 ballots.45

Bedrosian’s selection was controversial. No NL pitcher had been dominant, so each front-runner’s fans could cite statistics that supported their man. His five wins and 40 saves meant that he had played a role in more than half of his fifth-place team’s 80 victories. He observed: “I’m not going to say that I backed into it. I’m not looking at what starting pitchers did or didn’t do this year. I’m looking at what I was able to accomplish.”46 The Phillies rewarded him with bonuses totaling $225,000 for his All-Star selection, Cy Young Award, and the Rolaids Relief Man of the Year Award. The latter, like The Sporting News’s designation as NL Fireman of the Year, was not controversial, and the Philadelphia Sportswriters Association named him the Pro Athlete of the Year.

There was understandable optimism heading into the 1988 season.47 Then Bedrosian experienced chest pains while running sprints during spring training. The initial diagnosis was an acute strain,48 but a later diagnosis was “walking pneumonia”49 that put him out of action. He started the season on the 21-day disabled list after logging only one inning in spring training.50 After a brief (five games) rehab assignment with the Triple-A Maine Phillies, Bedrock finally took the mound on May 20 in San Diego and retired the only batter he faced in the sixth inning to strand two runners and preserve a 3-2 lead. He then returned to his role as the Phillies’ closer, finishing 49 games in 57 appearances and earning 28 saves. On September 25, his 95th career save for the Phillies broke Tug McGraw’s team record.51 After the season he was the only Phillies player offered a guaranteed multiyear contract, and he signed for three years at $1.45 million per year.52

The rumor mills went into overdrive in December when the Phillies traded for Jeff Parrett, who had appeared in 61 games for the Expos in 1988. GM Lee Thomas insisted that he had “no intention of trading” Bedrosian, whom he called “the best closer in baseball.”53 Bedrock, who had already expressed frustration over the limited number of save opportunities he had in 1988, explained: “I need work to stay sharp.”54 He had a strong spring training, allowing only six hits and a single run in nine games and started the regular season without allowing a run in his first five appearances.55 By the end of April, however, he had been in 11 games and had a record of 1-2 with only two saves. On May 15 he earned his second win despite serving up two gopher balls and acknowledged: “I’m not throwing my slider the way I want. … I have to keep on battling.”56

On June 16, Bedrosian gave up four runs in two innings and was the loser in a 15-11 slugfest won by the Mets. Two days later, he was traded to the San Francisco Giants, whose manager (Roger Craig) was sure that Bedrock would “get back on track with more work.”57 Bedrosian left the Phillies with a record of 2-3 and six more saves, raising his team record to 103 (since eclipsed). He was on the mound in Candlestick Park the day after the trade and earned a save. He then earned saves in his next four appearances, and finished the season with 17 saves and a 2.65 ERA for the Giants, who were champions of the NL West. Bedrosian appeared in four of the five NLCS games against the Cubs and got saves in the final three games, helping the Giants to win the NL pennant. He saw limited action (2⅔ innings in two appearances) in the “Earthquake” World Series that followed as Oakland swept the Giants in four games. Even though he had joined the team in midseason, Bedrock was voted a full share ($83,529.96) of the Giants’ losing World Series earnings.58

Bedrosian entered the 1990 season as San Francisco’s perceived “stopper.” Craig Lefferts, who had lost his closer role when Bedrock joined the Giants, had been granted the free agency he requested59 and had quickly signed with the Padres. Throughout spring training, Bedrosian had been worried about his 3-year-old son, Cody, who had been quite ill for several months. He reluctantly accompanied the team to Atlanta for Opening Day, but quickly went home to California when his wife, Tammy, called to say that Cody had gotten worse. The devastating diagnosis was leukemia, and Steve stayed with his son, missing the Giants’ first five games. Tammy finally persuaded him to rejoin the team, and he went to Candlestick60 on Sunday, April 15. He was sent to the mound in the ninth inning to protect a 3-2 lead over the Padres. He gave up four hits, including a two-run homer (on an 0-and-2 count) and lost the game, 4-3. He then showed his “leadership and character” by granting postgame interviews.61 At the end of the season, those traits were officially acknowledged when Bedrosian received the Willie Mac “Spirit, Ability, and Leadership”62 Award which annually recognizes the Giants’ “most inspirational” player.

Bedrosian struggled off-and-on throughout 1990, but salvaged the season by finishing well.63 In the three games after that disappointing first effort, he earned two saves. Then, on April 25, after holding the Pirates scoreless in the 10th and 11th innings, he was battered for four runs in the 12th and suffered another home loss. By June 1 he had earned seven saves, but did not get another until August 17. After earning two more August saves, he closed the season with seven saves and three wins (vs. one loss) in his last 11 appearances. His 1.46 ERA during that stretch lowered his season ERA by half a run to 4.20, still his highest since his call-up year. For the first time since that same year, Bedrosian walked more batters than he fanned. He had managed to equal his save total (17) from the previous year, and he had proved in the closing months of the season that he was still capable of closing games.

In December, the Giants traded Bedrosian to Minnesota for a player to be named later, and some pundits thought that he would become the Twins’ closer, allowing Rick Aguilera to become a starter.64 The pundits were wrong; Aguilera was still the closer, but Bedrosian got plenty of work, appearing in 56 games (but in only seven save situations). He finished the regular season with decent numbers (5-3, 4.42 ERA; six saves) and pitched briefly (1⅓ innings, two hits, no earned runs) in two ALCS games as the Twins beat the Blue Jays four games to one. Their World Series opponents were the Atlanta Braves.

Bedrosian appeared in three games against his former team — all played in Atlanta, all won by the Braves. His first two appearances were brief; he faced seven hitters and retired them all. His final appearance was less routine. He entered Game Five in the seventh inning with the Twins already trailing 7-3 and two runners on base. When he finally retired the side, he had given up two singles and a triple, allowing the two inherited runners to score, and was responsible for two more runs of his own. The Braves now led 11-3, and Bedrock was one of the five Twins pitchers whom the Braves “bent, folded, stapled, and mutilated”65 that night. The Twins rebounded, winning the last two games at home, and Steve Bedrosian finally had earned a World Series ring.

Since June of that 1991 season, Bedrosian had been undergoing multiple medical examinations, tests, and treatments (including acupuncture) in an effort to determine why he was experiencing numbness in the index and middle fingers of his right (pitching) hand.66 His once-dominant fastball now clocked only in the high 80s. He became a free agent at the end of the season and decided to take the next season off — a depressing “forced retirement” because his cold fingers had earned him a cold shoulder.67 He later said: “I really thought I was done. Just out of the game for good.”68

During his “retirement” on his 120-acre farm in Senoia, Georgia, while the 1992 season went on without him, the strange numbness subsided “suddenly and mysteriously.”69 Bedrosian contacted the Braves and was invited to spring training, where his comeback became “one of the best stories” of the spring.70 Apparently, the numbness was related to tobacco and stress, so he gave up tobacco, and son Cody’s leukemia was in remission. Bedrock was now “healthy and stress-free.”71

When the 1993 season started, Steve Bedrosian was a Brave again, and now he was the second oldest pitcher on the team. He struggled in April, losing two games that were tied when he took the mound. He acknowledged that he no longer had manager Bobby Cox’s confidence.72 His performance improved as he adjusted to not being the closer. He appeared in 49 games (pitching only 49⅔ innings, none of them save opportunities). He did not lose another game, and earned five wins. His 1.63 ERA was lowest on the team and he struck out more than twice as many batters as he walked. He was no longer “Kid Smoke,” but he could still be as solid as bedrock.

After the season the Braves avoided salary arbitration with Bedrosian by releasing him, but they signed him to a new contract two days later.73 His role in the 1994 Braves bullpen was similar to the previous year. At 36, he was now the team’s oldest pitcher. He pitched 46 innings in 46 games and was charged with two losses; he blew both of his save opportunities and earned no wins. His ERA rose to 3.33, but was second lowest on the team behind Greg Maddux’s 1.56. Once again, he became a free agent at the end of the season, but was signed to a new contract within days.

Bedrock was back with the Braves to start the 1995 season. He announced that he had rediscovered his fastball thanks to acupuncture,74 but that wasn’t enough. In August, after appearing in only 29 of the Braves’ 96 games, Bedrosian abruptly announced his retirement.75 He left with a 1-2 record and a 6.11 ERA. He had blown his only two save opportunities, and in

his final game had retired only one of the six batters he faced, giving up four hits and an intentional walk. He wasn’t there when the Braves finally won a World Series later that year, but he did receive his second World Series ring and a partial share of the winning team’s earnings.76

There was not another comeback. Steve Bedrosian’s fine major-league playing career was over after 14 seasons in which he appeared in 732 regular-season games (only 46 as a starter), pitching 1,191 innings. He won 76 games, lost 79, saved 184 (representing a 76.3 percent success rate), and “held” 38 more. He struck out 921 batters (seven per nine innings) and walked approximately half that many (443) unintentionally. Only half of the 52 players drafted ahead of Bedrock in 1978 made it to “The Show,” and only five (and just two pitchers) matched or exceeded his 14-year major-league career. One of those five was Hall of Famer Cal Ripken, who was drafted five slots before Bedrosian.

Bedrosian wasn’t through with baseball or the Braves. He agreed to participate in 1996 spring training and then join the Appalachian (Rookie) League Danville Braves as pitching coach.77

Steve Bedrosian wasn’t through with Georgia, either. The Massachusetts native stayed on the farm in Coweta County where he had settled during his first tour with the Braves. That’s where he and Tammy raised their five children (Stephen Kyle, Cody, Carson, Cameron, and Katelyn); that was now home. Bedrosian had been a bachelor when he joined the Braves in 1981.78 After he married singer79 Tammy Raye Blackwell in 198480 and later became a father, he brought to that role the same strength and determination that he showed on the diamond. The importance of his family is reflected in Steve’s choice of “the game of [his] life.” He didn’t choose a game in which he had excelled; he chose a game in which he gave up a tape-measure grand slam. He chose the May 10, 1994, game in which the Braves honored 6-year-old Cody Bedrosian, who was still battling leukemia. Cody got to throw out the first ball, and several Braves wore their pants knee-high and their sock stirrups high (Bedrosian style). Steve served up that homer and left the mound in the seventh inning with the Braves trailing 8-1 feeling that he “had let Cody down,” but the Braves tied the game with a seven-run rally in the ninth and won 9-8 in the 15th for “a storybook ending.”81 Cody recovered (thanks in large part to a bone-marrow transplant with brother Cam as the donor)82 and as of 2020 was doing well.

All four Bedrosian sons played baseball. Cody hung up his glove when he was 12.83 Kyle, Cameron, and Carson all played for the East Coweta High Indians, where their father often served as assistant pitching coach. Kyle, a lefty, went on to play for four years at Mercer University. In 2010, Cameron (Cam), whose middle name is “Rock,” was drafted out of high school in the first round by the Los Angeles Angels and made his major-league debut in 2014. He is a right-handed relief pitcher who averages more than a strikeout per inning and his nickname is “Bedrock.” Does that sound familiar?

Steve served on the Coweta County (Georgia) Board of Education for several years and was elected to the Coweta Sports Hall of Fame in 2009. He was already enshrined in the University of New Haven’s Athletics Hall of Fame (a 1996 inductee).

Last revised: February 12, 2021

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Almanac, the Baseball Cube, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the Sports Illustrated Vault.

Notes

1 www.dictionary.com.

2 Email from Steve Bedrosian, November 11, 2019.

3 eagletribune.com/sports/local_sports/eagle-tribune-athletes-of-the-century/article_35307211-902c-5f80-b368-fe56d94d3f2a.html.

4 University of New Haven Athletics, newhavenchargers.com/hof.aspx?hof=69.

5 Lou Pavlovich, “Horner and Gibson Stand Out in Selections,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1978: 42.

6 “Southern League Report,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1979: 43.

7 “Southern League Report,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1979: 43.

8 “Balboni Heads All-Stars,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1980: 52.

9 Ken Picking, “Braves’ Biggest Gain Was Down the Middle,” The Sporting News, November 15, 1980: 53.

10 Picking, “Dayley Atlanta’s Hill Prize,” The Sporting News, December 13, 1980: 50.

11 Tim Tucker, “Braves Willing to Deal Pitcher,” The Sporting News, December 12, 1981: 50.

12 Email from Steve Bedrosian, November 11, 2019.

13 Tucker, “Bedrosian’s Injuries Believed to be Minor,” The Sporting News, February 13, 1982: 39.

14 Tucker, “Eight Pitchers Battle for Braves Berths,” The Sporting News, March 13, 1982: 40.

15 Tucker, “Braves Are Leaning on Horner, Murphy,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1982: 21.

16 “Player Biographies: Steve Bedrosian,” Braves Illustrated: 1982 Yearbook: 47.

17 Fan: 1984 Atlanta Braves Official Program (Vol. 19, No. 4), 27.

18 George Cunningham, “12-0! Hotlanta’s Hotbraves Rewrite Record Book,” Atlanta Constitution, April 21, 1982: 1.

19 Email from Steve Bedrosian, November 11, 2019.

20 Tucker, “Bedrosian Rates ‘Awesome’ Label,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1982: 17.

21 Tucker, “Bedrosian Rates ‘Awesome’ Label.”

22 Tucker, “Bedrosian Rates ‘Awesome’ Label.”

23 Earl Lawson, “Reds Setting Sights on Atlanta Slugger,” The Sporting News, December 13, 1982: 52.

24 Chris Mortensen, “Mr. Finesse and Kid Smoke,” Braves Illustrated: 1983 Yearbook: 23.

25 Tucker, “Braves Face Huge Payroll,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1983: 36.

26 Bill Conlin, “Phils Seek a Starting Pitcher,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1983: 48.

27 Tucker, “Braves Seek Perez’s Replacement,” The Sporting News, February 6, 1984: 49, 52.

28 Gerry Fraley. “Barker. McMurtry Out of Rotation,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1984: 19-20.

29 Fraley, “Do Braves Lead Chase of Sutter?” The Sporting News, December 10, 1984: 51.

30 Sandy Keenan, “10 Atlanta Braves,” Sports Illustrated, April 15, 1985.

31 “Steve Bedrosian,” Alchetron (alchetron.com/Steve-Bedrosian).

32Fraley, “Braves Gear Up for Slugfests,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1985: 44.

33 Peter Pascarelli, “Two Trades Have Ripple Effect,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1985: 41.

34 Bill Conlin, “NL Beat,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1986: 40.

35 Conlin, “NL East,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1986: 18.

36 Pascarelli, “A Bullpen Bounce-Back by Phillies’ Bedrosian,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1986: 17.

37 Conlin, “NL East,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1986: 18.

38 Murray Chass, “Baseball’s Best Trades,” The Sporting News, August 25, 1986: 14.

39 Pascarelli, “A Bullpen Bounce-Back.”

40 “Notebook, NL East, Phils,” The Sporting News, February 2, 1987: 42.

41 Pascarelli, “N.L. East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1987: 24.

42 “N.L. East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, July 13, 1987: 27.

43 Dave Nightingale, “A Relapse by the Rabbit?” The Sporting News, July 27, 1987: 45; YouTube video Alchetron.

44 “NL East,” The Sporting News, August 17, 1987: 17.

45 Murray Chass, “Phillies’ Bedrosian Cy Young Winner,” New York Times, November 11, 1987.

46 Bill Brown, “Cy Young Award a Real Bonus,” The Sporting News, November 23, 1987: 45.

47 Brown, “Bedrock Digs for Solid Start,” The Sporting News, March 27, 1988: 24.

48 “Notebook: NL East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1988: 37.

49 “Notebook: NL East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1988: 33.

50 “Notebook: NL East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1988: 49.

51 “Notebook: NL East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, October 10, 1988: 23.

52 Chass, “Sax & Marshall Set Free,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1988: 44.

53 “Notebook: NL East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1989: 17.

54 “Notebook,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1989: 19.

55 “Notebook: NL East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1989: 21.

56 “Notebook: NL East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1989: 23.

57 Brown, “Thomas Shakes Up Phillies,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1989: 22.

58 Chass, “A’s World Series Checks Set Record,” The Sporting News, November 11, 1989: 61.

59 “Notebook: NL West: Giants,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1990: 52.

60 Jack Wilkinson, “Steve Bedrosian,” The Game of My Life (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2007), 64.

61 Art Spander. “Cody Bedrosian Can Be Proud of His Father,” The Sporting News, May 7, 1990: 55.

62 “Willie Mac Award,” baseball-almanac.com/awards/willie_mac_award.shtml.

63 “Bedrosian Salvages ’90 with a Strong Finish,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1990: 17.

64 “Notebook: AL West: Will Bedrosian Make Aguilera a Starter?” The Sporting News, December 17, 1990: 35.

65 Nightingale, “Twins Star in the Late Show,” The Sporting News, November 4, 1991: 10.

66 Wilkinson, 62.

67 Sean Gavitan, “Life’s Highways;” Fan (Atlanta Braves magazine), 1993: 56.

68 Wilkinson, 63.

69 Wilkinson, 63.

70 Pascarelli, “Baseball Report: Around the Bases,” The Sporting News, March 15, 1993: 16.

71 Pascarelli, “Baseball Report: Around the Bases.”

72 Bill Zach, “Baseball: NL East/West: Atlanta Braves,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1993: 20.

73 Tim Luke, “AL/NL: Atlanta Braves: Bedrock’s Back,” The Sporting News, November 22, 1993: 43.

74 Zach, “NL East: Atlanta Braves,” The Sporting News, May 8, 1995: 18.

75 Zach, “NL East: Atlanta Braves,” The Sporting News, August 21, 1995: 16.

76 Telephone conversation with Steve Bedrosian. November 5, 2019.

77 Zach, “NL: Atlanta Braves,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1995: 44.

78 “Career Statistics: Steve Bedrosian,” Braves Illustrated; 1981 Yearbook: 66.

79 Email from Steve Bedrosian, November 11, 2019.

80 “Steve Bedrosian,” Atlanta Braves 1994 Team Yearbook: 25.

81 Wilkinson, 65.

82 Telephone conversation with Steve Bedrosian, November 5, 2019.

83 Wilkinson, 66.

Full Name

Stephen Wayne Bedrosian

Born

December 6, 1957 at Methuen, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.