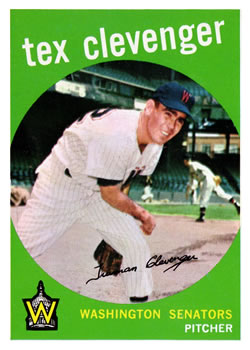

Tex Clevenger

Right-hander Truman Eugene Clevenger was born and raised in Visalia, California, went to California State University at Fresno, and signed with the Boston Red Sox to play professional baseball. At no point in his minor-league career did he work for a team that played in Texas. But he still picked up the nickname “Tex” and it stuck with him throughout his life. The nickname came from Boston teammate Johnny Pesky, who saw a resemblance to former Red Sox pitcher Tex Hughson.1

Right-hander Truman Eugene Clevenger was born and raised in Visalia, California, went to California State University at Fresno, and signed with the Boston Red Sox to play professional baseball. At no point in his minor-league career did he work for a team that played in Texas. But he still picked up the nickname “Tex” and it stuck with him throughout his life. The nickname came from Boston teammate Johnny Pesky, who saw a resemblance to former Red Sox pitcher Tex Hughson.1

Both of Truman’s parents were from Missouri, but he reportedly hadn’t been named after Harry Truman.2 His father Jess Clevenger worked as a tractor operator in Visalia at the time of the 1940 census. Twenty years earlier, he worked as a farm laborer. Mother Golden Clevenger worked with fruit on a seasonal basis. Their eldest was a daughter, Frances. Truman was second, born in Visalia on July 9, 1932. He had a younger brother he called Bill.

Truman attended Visalia High School and went on to 3½ years at Cal State Fresno. When he had started high school, there seemed to be no way Clevenger would become a baseball player; he was 4-feet-11 and weighed 86 pounds. He never played in freshman year, but a new coach – Hank Viden – came on in his sophomore year and declared, “Anyone that wants to play baseball will play baseball…I started as an outfielder and the coach asked if anyone wanted to pitch. That’s how I got started.”3

He was signed to a Red Sox contract by scout Tom Downey for the bargain price of $3,000.4 He had truly begun to attract attention on March 21, 1953, when he threw his second no-hitter for the Fresno Bulldogs against the College of the Pacific team. He had no-hit the same college team in 1952. He struck out 20 batters, while going 6-for-6 at the plate with three triples, two singles, and a double.5 Fresno won, 21-0. On June 9, he signed a contract with the Red Sox. Naturally, there were other teams in pursuit and three had reportedly offered more money, but Clevenger preferred the idea of pitching in San Jose, where the Red Sox had a farm club. “We got him so low,” Boston’s farm director Johnny Murphy said, “that the other three big league teams which wanted to give him more money had us investigated. They were surprised that we got him so low.”6

There may have been a more humble reason. Clevenger wanted to make it to the big leagues, of course, but he knew he lacked something. “The scouts tell you how good you are. But you can’t fool yourself.”7 He knew he needed to develop a better curveball, and that getting by on the fastball alone wasn’t going to cut it in the majors. Brother Bill was a catcher at Fresno State and the two worked as a battery, and then caught him every other day over the winter of 1952-53, as Truman worked on his curve.8

He was already married, in September 1952, to Margaret E. Renner. Late in 1953, they had a daughter, Janet. A son Martin (named after former teammate Marty Keough) was born in July 1958.

He was assigned to the San Jose Red Sox of the Class-C California League. In his debut game, he threw a one-hitter, beating Ventura, 8-2. He had an exceptional season, with a 16-2 record and a 1.51 earned run average, leading the league in both stats, while pitching 18 complete games in 19 starts. He struck out 157 batters in 155 innings. He was named Rookie of the Year. San Jose finished 18 games ahead of second-place Bakersfield in the standings.

Clevenger was listed as 6-feet-1 and 185 pounds. He still hadn’t finished college yet; his major was viticulture. He was quick on his feet, though. When presented an award at a Fresno Hot Stove League banquet, and told he could become as great a southpaw as fellow Fresno pitcher Dutch Leonard, he said he was embarrassed by all the praise but that “if I’m going to be as great a southpaw as Dutch Leonard, I’ll have to start all over again. I’m right-handed.”9 He was also presented the Win Clark Trophy at a February banquet in Los Angeles, presented each year to the top California rookie in Organized Baseball.10

He trained with the Red Sox at Sarasota in the spring of 1954. There was thought of him making the Boston ballclub, but on March 29, manager Lou Boudreau sent him to Louisville. Boudreau said, “Clevenger is One of the Finest Prospects I Have Ever Seen.”11 But he worried that bringing him to Boston would be rushing him too much. After watching his most recent outing, “I saw his inexperience and pressure was starting to catch up with him…[rather than only use him occasionally] it’s better that he go out and pitch regularly.”12

However, even before the season began, he was recalled just one week later on April 6.

Clevenger’s debut came on April 18. The Red Sox were losing to the Philadelphia Athletics, 6-4, after eight innings. Clevenger pitched the top of the ninth and retired the side on four pitches. After another hitless inning of relief some nine days later, he was given a start – he only learned he was starting an hour before the game — and he won the May 7 game, beating the Washington Senators, 7-6. He had allowed only one hit through the first five innings, but then, he admitted, “I ran out of gas.”13 In the sixth, he only got one out and was charged with four runs. Ellis Kinder excelled in relief and preserved the game for Clevenger. Lou Boudreau said he needed to learn to pace himself: “Clevenger was making each pitch like it was a World’s Series.”14

He lost his next four decisions and at that point had an ERA of 5.08. “They don’t let you fool them very much in this league,” he said. “You can’t make mistakes on these boys and get away with it.”15

He only started one more game for the rest of the season – and in that one (on July 3), he only faced two batters, having to leave due to an hereditary medical issue: “slight curvature of the spine” which may have resulted in a pinched nerve.16

There was a dispute over his military status. With a wife and daughter, he had been declared exempt with 3-A status. The Visalia board, however, was overruled by the state board, which declared him 1-A. This prompted a member of the Visalia board to resign his position. When Clevenger was given a physical in Boston, he was failed due to his back condition.

By season’s end, he had appeared in 23 games (eight starts), throwing 67⅔ innings, with a 2-4 record and a 4.79 ERA.

Clevenger spent the entire 1955 season with the Louisville Colonels. Mike Higgins had become the new manager. Working in Triple-A, Clevenger started 21 games (nine complete games) and relieved in 18 others. He was 9-13 in his mound work, with a 3.77 ERA.

After the season was over, on November 8, he was part of a nine-player trade with the Washington Senators. Boston acquired Bob Porterfield, Johnny Schmitz, Tommy Umphlett, and Mickey Vernon, giving up minor-leaguer Al Curtis, Dick Brodowski, Neil Chrisley, Clevenger, and Karl Olson. The Sox went for veterans such as Porterfield and Vernon, and the experienced Schmitz, in exchange for a number of their younger prospects. It was the opposite of a “youth movement,” dubbed by the Boston Globe’s Harold Kaese as “Going Without the Kids.”17 It was Calvin Griffith’s first major move after the death of his father elevated him to the presidency of the Senators. “The ball club needs youngsters to build for the future,” wrote Bob Addie of the Washington Post. “Maybe this combination won’t work but you must give Calvin credit for trying.”18

In fact, the Red Sox had pretty much thought he was done. And indeed his arm had rebelled, Clevenger recalled decades later: “I couldn’t even raise my arm to comb my hair.”19 Exercise and Novocain eventually helped him bring back his arm.

Clevenger started the 1956 season with the Senators. He worked in 20 games, with only one start (another very short one, facing only four batters in Boston on May 27 before being quickly replaced for ineffectiveness). He had no decisions, but after his final relief appearance on June 13, he had a 5.40 ERA and later that same day he was optioned to Louisville – now the Senators’ Triple-A club. The Post’s Shirley Povich had already concluded, before the season began, that “none of three pitchers obtained from the Red Sox…has generated any great hopes that they will mature into major leaguers.”20

The Colonels finished in last place, but Clevenger – he turned 24 during the season – had a particularly rough year, with a 2-11 record (losing nine in a row at one point) and a 5.94 ERA.

One might not have expected it, but Clevenger worked as a major leaguer for the Senators for the next four seasons, 1957 through 1960. He mixed roles, but worked primarily in relief, working an average of more than 52 games each year, with his 55 appearances leading the league in 1958. He always started a few games each season, though, ranging from four in 1958 to 11 in 1960. Somewhat more than half the games in which he relieved, he was the pitcher who closed out the games, though considering the way he was used he was not who one might today call the closer.

In 1957, he was 7-6 with a 4.19 ERA. Through June 12, he was 5-0, winning five games in 15 days, but then things evened out as the season wore on. Manager Cookie Lavagetto, nevertheless, said, “One of my own private heroes this year is Tex Clevenger.”21 He added, “I don’t care what the figures show. Clevenger has been our most useful pitcher and it is a pleasure for me to say so. A year ago he was a discredited pitcher who didn’t seem to have any future in the game. He bounced back big, and it took a lot of perseverance on his part and he showed us a lot to admire…It was when we were foundering for pitchers that he came through for us.”22

As a fielder, he committed three errors but in his five seasons with the Senators, he only committed a total of six.

As a batter, he was usually a pretty sure out. In his eight seasons in the big leagues, he hit .157 with a total of 11 RBIs. Five of those came in 1957, when he hit for a .212 average.

In 1958, his pitching won nine games and lost nine, with a 4.35 ERA. That was the year he said that he earned “my only claim to fame – if you can call it that.”23 The Senators had lost 18 games in a row. Lavagetto turned to Clevenger and gave him his first start of the season, which he won against Cleveland, a six-hitter. So he told Arthur Daley, though no such game can be found. The Senators lost the last 13 games of the season, but that was the longest losing streak of the year. There was another moment which resulted in a brief story in The Sporting News. In the first game of the May 11 doubleheader at Yankee Stadium, Elston Howard hit a ball in the bottom of the seventh, which struck Clevenger in the leg “into foul territory near first base. First Sacker Norm Zauchin fielded the ball from a prone position and flipped to Clevenger, who crossed the bag ahead of Howard.”24 He thus earned both an assist and a putout on the same play.

After a bit of a holdout for higher pay, he had an 8-5 (3.91) year in 1959, working in an even 50 games. His best game of the year was the four-hit shutout over the Tigers on September 14.

There were some bad games, too. He only secured one out in a start against the Yankees on May 15, 1960. In the third of an inning before he was pulled, he wound up assessed five runs and ultimately lost the game. On August 17, however, he pitched 4⅓ innings of scoreless relief – through the 12th inning – and saw his team score four times in the top of the 12th for the win. This was last year with the Senators – 1960; he was 5-11 but with a steady 4.20 ERA.

When the American League held an expansion draft to help stock two new teams – the Angels and the Senators – Washington elected not to protect Clevenger and he was drafted by the Los Angeles Angels as the seventh pick in the December 1960 draft.

He was pleased, of course, to be playing in California again, and he thought the team had done a good job assembling personnel for its first season. The Angels, he said in February, “are a better ball club right now than the Washington Senators team I played with in 1957, 1958, and 1959.”25

He wasn’t wrong. In fact, the Angels placed eighth in what was now a 10-team American League in 1961, nine games better than the ninth-place Senators. Clevenger, however, wasn’t with them for most of the season. He found himself with a first-place team.

In his first seven outings for the Angels, he didn’t give up an earned run. He gave up his first one in an April 30 game against Kansas City, but he gave up only one and he won the game in relief. In early May he won another game, then lost one, then earned a save – and on May 8 he was traded to the New York Yankees, with Bob Cerv. The Yankees gave up Ryne Duren, Johnny James, and Lee Thomas in the trade. Though Clevenger “had become a great favorite” among California players and fans for his early-season work, the Angels felt they would get more out of Duren in the long run.26

Clevenger was understandably pleased. “Every pitcher dreams of pitching for the Yankees…When Washington didn’t protect me last winter, but put me in the pool for drafting by the two teams, I had misgivings. I was only 28 years old, but it had to make me wonder if I was approaching the end. This uniform settles all doubts. It’s the perfect morale booster.”27 The Yankees, it was written, “had been enamored with Clevenger for four years while he toiled for the Senators.”28

Clevenger had nothing but praise for the Yankees organization. “As far as the mechanics of pitching are concerned, they don’t do it any different here…But there’s a difference inside [he said, tapping on his chest]. When you put on this Yankee uniform, you have a little more pride, a little more confidence.”29

However, Tony Kubek had a more poignant take on Clevenger’s service with the Yankees, writing years later, “Some guys were never meant to be a Yankee. There was Tex Clevenger, who had a vicious sinker and slider. You’d watch him throw on the sidelines and in batting practice and you’d figure this guy was one of the better pitchers in the league. But when Ralph Houk put Tex on the mound, something happened to him. For whatever reason, he lost his stuff somewhere between the bull pen and the mound; it’s like he just couldn’t adjust to being in New York and having to win.”30

He pitched in 21 games for the 1961 Yankees, winning one and losing one, with an earned run average of 4.83. It was the 15-5 closer Luis Arroyo who earned the bulk of the credit in the bullpen. Clevenger saw Mickey Mantle launch 54 homers and Roger Maris top that with 61. Clevenger later said, “I was throwing in the bullpen and the ball landed about 15 feet away from me in the stands.”31

The Yankees won the pennant and only took five games to beat the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series. Clevenger was eligible, but saw no postseason action.

In 1962, he worked the same number of game for the Yankees as he had in 1961 – 21 games, all in relief. Houk had still expressed faith in him despite the shortcomings he had shown in the latter half of 1961: “I know Tex is a better pitcher than that. It’s just a case of straightening himself out and I somehow feel he’ll do it.”32 Clevenger himself thought it was more than a mechanical matter; “There’s a sort of ease and relaxation when you’re with a second-division club that gets in your blood….Sure, we all try to win. But if we lose, well, shucks, you’re with a club that isn’t expected to win too often and you shrug it off. But when you come to a pennant winner like the Yankees, boy, that sure is a big difference. You find yourself with a club where every game means something and a lot of money can ride on every pitch if the game is close. It’s something you have to adjust yourself to. I think things will be different for me this year.”33

He had little work in spring training, and none at the beginning of the 1962 season, so on May 9 he was optioned to the Richmond Virginians. He was 1-1, 1.80 in four games, but on May 21 Luis Arroyo was put on the DL due to inflammation of the tendons around the elbow of his pitching arm. Clevenger was recalled. He was 2-0, 2.84, with the Yankees. Once again, he was eligible for the World Series, but once again his services were not called upon, though the World Series went the full seven games against the San Francisco Giants. But he was a World Champion for the second year in a row and was awarded a full Series share.

In early April 1963, he was sent to Richmond again. He was stunned and thought he stood a good chance to hook on with another team. It didn’t happen, though, and he played out the season. It was his last in professional baseball. He had a good 3.09 ERA but a record of 4-9.

He signed his contract with Richmond for 1964, but never reported. In late March, he was given his outright release.

After baseball, he became an insurance underwriter for Mutual of New York in Visalia and worked at that at least into the early 1970s. He also had a TV sports show. Not long after he got out of baseball, he and his wife Margaret divorced.

By 1974, he was seen in the Porterville, California City Directory, working as a salesman for Billingsley and Madland, an automobile dealership. In January 1976, he married again, to Dona Billingsley.

He and Dona purchased the car dealership, renamed it Clevenger Ford, and operated it until they sold it around 1995. It operates in 2017 as Porterville Ford. He attended a number of banquets for this and that, and was inducted into the Fresno State Hall of Fame. Clevenger also hosted some golf tournaments in Porterville. Dona Clevenger says that Tex very much enjoyed telling stories of his days in baseball. He kept in good touch with fellow ballplayers such as Joe DeMaestri, Marty Keough, and Karl Olson. The Clevengers went to a number of old-timers’ games and reunions over the years with the Yankees and Angels.34 Dona called him “Tex” – after the nickname was initially bestowed on him, it became how he was known to friends and family, even in his retirement years.

In 2007, Tex Clevenger had his number at Fresno State retired. It was a “bittersweet” day, though, as he buried his brother Bill that same day.

In his later years, Tex Clevenger was in a care home in Visalia, necessitated by Alzheimer’s disease. He was diagnosed in 2008, and the disease developed to a point around 2014 that extra care was needed. His color was reported good, and he seemed strong. “He seems pretty happy with it,” Dona Clevenger said. Some residents with the disease, of course, have difficulty adjusting and find it difficult to, for instance, sit with certain others. This has not been the case with Tex. “He’s very nice. He’s real easy. He likes everybody there and everybody likes him.”35

He died at the age of 87 on August 24, 2019.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by David Lippman and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Clevenger’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Burton Hawkins, “Clevenger Hurled Path to Senators in 1954,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), February 24, 1956: 47. The Christian Science Monitor’s veteran baseball writer Ed Rumill had agreed – “he reminds you of Tex Hughson in so many ways.” See “Johnny Murphy Takes Tru Clevenger In Hand,” March 30, 1954: 14.

2 Bob Holbrook, “Clevenger Looks and Hurls Like Hughson,” The Sporting News, March 3, 1954: 23. Holbrook wrote that he was initially given the nickname Clem.

3 Alex K. W. Schultz, “Clevenger Recalls Past Glory,” McClatchy-Tribune Business News, Porterville Recorder, August 3, 2007.

4 Ed Rumill, “Red Sox Pitcher Truman Clevenger Drew Compliments from Stengel,” Christian Science Monitor, February 16, 1954: 14.

5 INS, “Fresno Pitcher Hurls 2nd No-No,” The Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), March 22, 1953: 60.

6 Hy Hurwitz, “Blocked on Trade, Bosox to Dig Hurler in Own Early Camp,” The Sporting News, January 20, 1954: 16.

7 Bob Holbrook.

8 Ibid.

9 John Drohan, Day of Bashful Big League Rookie Past,” Boston Traveler, February 16, 1954: 43.

10 Frank Finch, “Red Sox Farmhand Hailed As California’s Top Rookie,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1954: 24.

11 Ed Rumill, “Johnny Murphy Takes Tru Clevenger In Hand.”

12 Joe Cashman, “Red Sox Drop Clevenger, 3 More Rookies to Minors,” Boston Record, March 30, 1954: 21.

13 John Drohan, “Clevenger Passes First Mound Test,” Boston Traveler, May 8, 1954: 6.

14 Hy Hurwitz, “Bosox Rookie Pair Wins Place in Sun on Rainy-Day Jobs,” The Sporting News, May 19, 1954: 5. The Red Sox had high hopes both for Clevenger and Tom Brewer.

15 Bob Holbrook, “Learning Something Every Game – Clevenger,” Boston Globe, May 9, 1954: C57.

16 “Clevenger Has Spine Curvature,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1954: 36.

17 Harold Kaese, “Porterfield and Vernon Give Sox More Depth,” Boston Globe, November 9, 1955: 1.

18 Bob Addie, “Bob Addie’s Column,” Washington Post, November 9, 1955: 30.

19 Alex K. W. Schultz.

20 Bill Cunningham, “Yankees Honest, Sox Cut-Raters,” Boston Herald, April 11, 1956: 29.

21 Shirley Povich, “Cookie Names Clevenger His Personal Hero,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1957: 18.

22 Ibid.

23 Arthur Daley, “Sports of The Times: The Hungry Hurler,” New York Times, May 23, 1961: 51.

24 “Assist, Putout for Clevenger on Drive Caroming Off Leg,” The Sporting News, May 21, 1958: 26.

25 Associated Press, “Clevenger Rates Angels Over Old Nats,” Washington Post, February 8, 1960: A26.

26 Braven Dyer, “Angels Swap Clevenger, Cerv for Yankees’ Duren,” Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1961: C1.

27 Arthur Daley.

28 Harry Grayson, “Yanks Needed Clevenger, And, as Usual, Got Him,” New York World Telegram Sun, May 11, 1961.

29 Ed Rumill, “There’s A Difference Inside,” Christian Science Monitor, May 29, 1961: 7.

30 Tony Kubek and Terry Pluto, “Sixty-One, The Team, The Record, The Men,” MacMillan, New York, 1987

31 Alex K. W. Schultz.

32 John Drebinger, “Clevenger Ready to Reward Yanks,” New York Times, March 30, 1962: 15.

33 Ibid.

34 Author interview with Dona Clevenger, February 18, 2017.

35 Ibid.

Full Name

Truman Eugene Clevenger

Born

July 9, 1932 at Visalia, CA (USA)

Died

August 24, 2019 at Visalia, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.