Warren G. Harding

“President Harding’s interest in Baseball and his many kind acts toward individual players was [sic] deeply appreciated by all of us.”1

“President Harding’s interest in Baseball and his many kind acts toward individual players was [sic] deeply appreciated by all of us.”1

None other than Babe Ruth expressed this sentiment in his handwritten condolences to the widow of Warren G. Harding, the 29th President of the United States. Harding died while in office on August 2, 1923, in San Francisco, California. As with other presidents, a period of mourning and multiple ceremonies followed his death. The final funeral service was held on August 10 in his hometown of Marion, Ohio, where he would rest for eternity.2 Major-league baseball stadiums were silent that day as the nation grieved. The following day, seemingly speaking for all of baseball, the Babe took pen in hand.

Like most children of the period, Harding had played baseball as a child growing up in Ohio. When he moved to Marion as a 17-year old, he befriended Bob Allen, who went on to play seven seasons in the majors. After his playing days, Allen was a minor league owner for nearly 30 years.

From 1907 through 1911 Harding owned an interest in the Marion Diggers in the Class D Ohio State League.3 One of his favorite players was Wilbur Cooper, who won 17 for Marion in 1911, leading to his 15-year major-league career. Supposedly Harding recommended Cooper to the Pittsburgh Pirates, who signed Cooper in 1912 after a season in the American Association with Columbus, Ohio.4

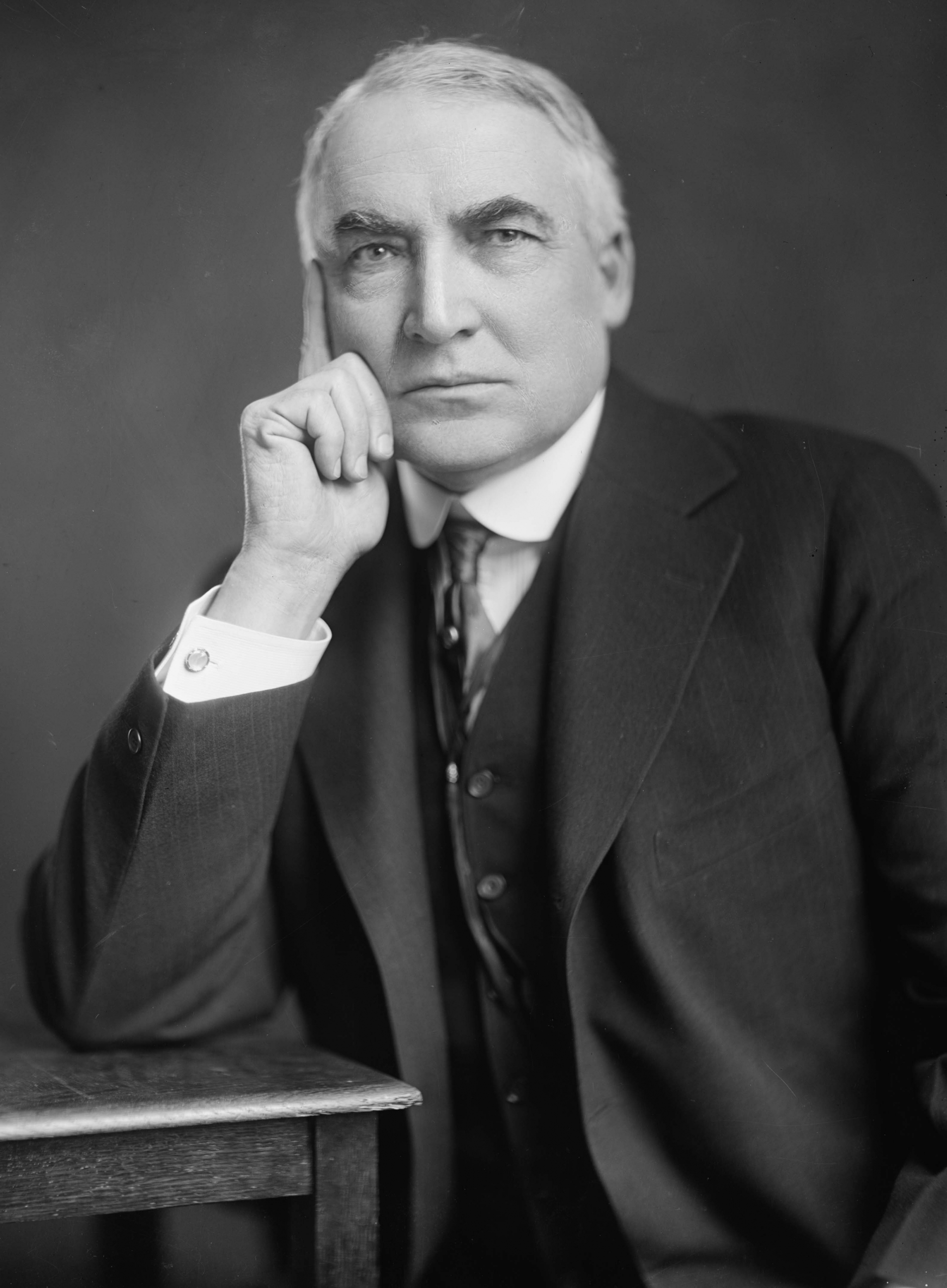

Born November 2, 1865, in Blooming Grove, Ohio, Warren Gamaliel Harding was the first child born to George Tyron and Phoebe Elizabeth (Dickerson) Harding.5 The Harding family originated in Scotland and had been in America since before the Revolution. Warren was able to trace his ancestry back five generations in order to apply for membership in the Ohio Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution. Phoebe’s family was of Dutch descent and lived close to the Harding farm.

George and Phoebe had become sweethearts at an early age, but her parents were resistant to an early marriage before George had established himself. When he returned from service in the Civil War, the time was right for the wedding. He worked on the farm, built a home for their family, and eventually began the study of medicine.6 Warren was joined by siblings Charity, Mary, Eleanor, Charles, Abigail, Caroline, and George, Jr. The family moved to Caledonia, Ohio, in 1871 as G.T. Harding established his medical practice. In 1882 they moved to Marion.

Warren was educated by both his mother, who called him ‘Winnie’, and the local schools before attending the short-lived Ohio Central College in nearby Iberia. He taught school for a year, then studied law for a year.7 Feeding on one of his hobbies, he organized the Citizens’ Cornet Band and played every instrument “but the slide trombone and the E-flat cornet.”8

Harding began his newspaper career with the Marion Daily Mirror in 1882. The other newspaper in town, the Marion Star, became available in a sheriff’s auction in 1884. He and a few other investors paid $300 for the paper, and Harding found the first stage of his life’s work as its editor.9

Harding worked diligently to make the newspaper successful and respected. He became an accomplished newspaperman and fostered the revival of the Star. By 1889 the paper was “the leading Republican organ in its section of Ohio.” He used his status as editor to enter politics and campaign for the state senate to represent a district that included Logan, Marion, and Union counties.10 He won handily and served two terms in Columbus.

Harding had grown to be a “large, handsome man with a robust physique… He had a grace of bearing and a charm of manner that made him a distinguished figure… [with] intelligence, energy, courage, and determination.11 Harding’s presidential campaign manager, Harry Daugherty, often said Harding “looked like a President.”12

The ladies of Marion took notice of Harding, especially a young divorcée with a son, Florence M. Kling. In 1880 she had created a sensation by eloping with Henry DeWolfe and getting married against her parents’ wishes. Her father, Amos H. Kling, was generally regarded as the richest man in the county.13 The marriage produced a son named Marshall, but ended soon after when the couple proved to be incompatible.

Florence returned to her maiden name and Marshall was adopted by her father. She and Harding began to plan their life together during his first term in Columbus. She designed their home in Marion, where they were married on July 8, 1891. Florence became the business manager of the Star during one of Harding’s absences to recover from fatigue at a sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan.14 She created a circulation department with a bevy of newsboys to scour the town. Most importantly, she proved much more adept at financial matters than her husband.15 Indeed, Harding gave Florence a deferential nickname: “The Duchess.”

Florence suffered from nephritis and required surgery in 1905. While she was convalescing, Warren began a long-running affair with Carrie Fulton Phillips, the wife of a neighbor. During her lengthy recovery, Florence became dependent upon a homeopathic doctor named Charles Sawyer.16 Sawyer followed the family to Washington where, besides offering medical advice. he became a player in Harding’s frequent poker games.

Harding became lieutenant governor of Ohio in 1904 and served two years. He returned to politics in 1910 with an unsuccessful bid for the governor’s office. In 1914 he was elected to the U.S. Senate and the family split their time between Washington and Marion. Harding continued to hone his considerable people skills and could be found at all manner of events both political and social.

As a senator, Harding was difficult to label or categorize politically beyond saying he was a Republican. He believed in high tariffs and was opposed to many of Woodrow Wilson’s ideas, but he seldom showed any passion for the issues and seemed very middle of the road. Two of his most notable “yea” votes were for women’s suffrage and prohibition. The fact that he missed more than a third of the votes during his tenure makes a definitive analysis of his leanings problematic.17

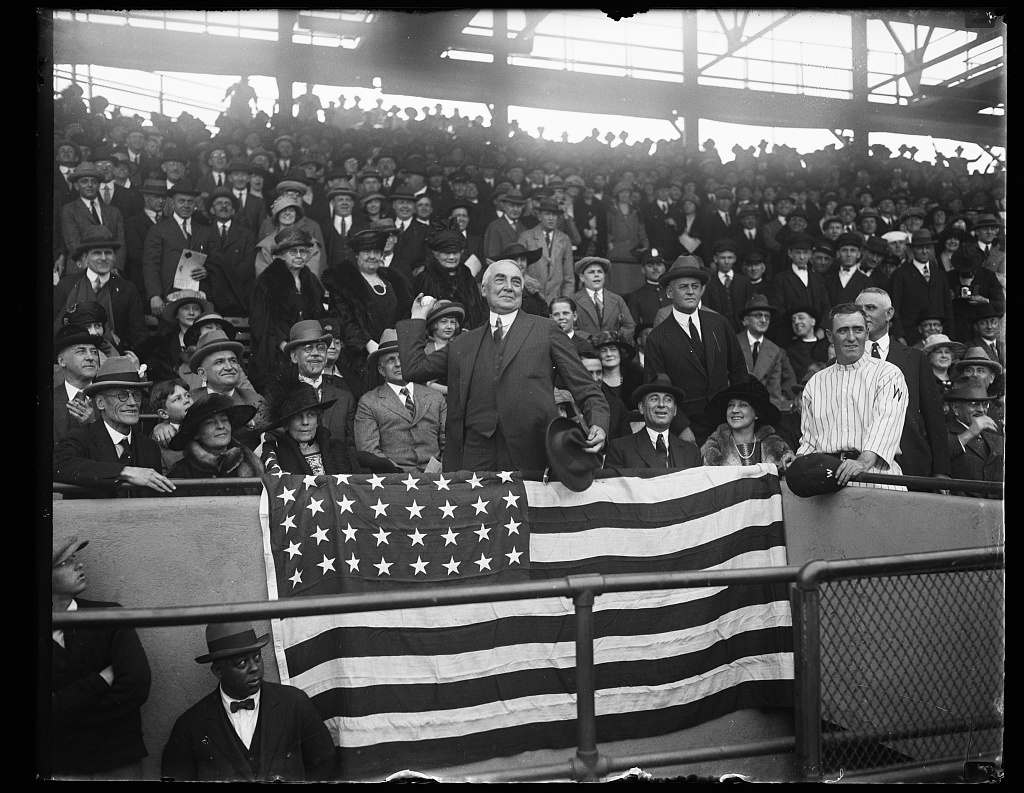

President Warren G. Harding, center, throws out the ceremonial first pitch before a Washington Senators game on April 13, 1921, at Griffith Stadium in Washington, DC. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, NATIONAL PHOTO COMPANY)

One area where Harding did show enthusiasm was at the ballpark. He and Florence were frequent visitors to watch Clark Griffith’s teams perform. Harding took “more than an academic interest in the game … and could score a game as neatly and concisely as any official scorer.” He understood the game well, even the most trivial nuance. A true fan, he stayed until the last man was out.18 Quick to pick a team to root for, he said in an oft-quoted line, “There is the soul of the game.”

In 1920 no candidate went into the Republican convention in Chicago with even a third of the delegates. Harding was Ohio’s favorite son and considered a dark horse at best. After the first few ballots it was clear that none of the frontrunners — Hiram Johnson, Leonard Wood, and Frank Lowden — would be able to get a clear majority. Harding was proposed as an alternative and on the tenth ballot he was chosen to represent the party. He named Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts as his running mate.

Hidden from the public eye was the arrival of Carrie Phillips at the convention. She was bribed by the Republican leadership to keep silent and sent on a long trip. Party officials must also have known of Harding’s dalliance in Washington with a much younger woman, Nan Britton, who would claim that she conceived a child in Harding’s Senate office. Her daughter, Elizabeth Ann Britton, was born in 1919. Harding never acknowledged paternity of Elizabeth Ann, but he did provide financial support that ended when he died. In 1927, Britton authored a book called “The President’s Daughter” in which she stated her case. The standard response to her claims was that Harding had suffered from mumps as a child and was infertile, which invalidated her assertion.19

Albert Lasker, an advertising executive from Chicago, was hired to create an image for Harding and guide his campaign. When a newsreel of Harding playing golf surfaced in July, Lasker determined Harding needed a man-of-the-people image. Golf was an elitist sport played by the rich and was out of reach to the bulk of society. Harding came from a small city (about 28,000 in 1920) and had owned part of the local ballclub. What better way to make Harding into a man of the people than to spotlight his love of baseball?20

Harding and his advisors coined the phrase “Return to Normalcy” for their vision of a Harding presidency. Exactly what that Normalcy would be was never really spelled out. In a speech delivered on May 14, 1920, he called for healing, normalcy, restoration, adjustments, and serenity without offering any specifics on how to achieve any of them.21When he took office, the legislative agenda featured protective tariffs, tax breaks for corporations, and an immigration quota system that sharply reduced the flow of Europeans to the USA.

In the presidential election, Harding was opposed by Ohio Governor James M. Cox. While Cox traveled extensively during his campaign, Harding stole a page from President William McKinley (also from Ohio) and conducted a “front porch” presidential campaign. He gave speeches from the front of the house with his constituents traveling from all over to hear his addresses. The press gave him extensive coverage because he provided them with a work area –the Press House — just behind his home.

In keeping with the theme of baseball, Lasker arranged for the Chicago Cubs to stop in Marion and play an exhibition game during a road trip to Pittsburgh and the East. He tried to get either the Cincinnati Reds or Cleveland Indians to provide the opposition but had to settle for the local Kerrigan Tailors team. The game took place on September 2.

The festivities opened in the morning when Harding addressed the teams and onlookers with what has become known as the “Team Play” speech. Harding’s oration was laden with baseball metaphors. He was extremely critical of President Wilson’s policies at home and abroad, claiming that the Democrats had “muffed disappointingly in our domestic affairs and then struck out in Paris.”

In a personal jab at Wilson, Harding proclaimed that the nation had “too many men batting over .300 to rely on one hitter.” He also addressed the Cubs directly and noted that there are progressive ideas but that many “rooters” were happy with the old-fashioned Tinker-to- Evers-to-Chance. A longtime Cincinnati Reds fan, Harding opined that he rejoiced as much in their victory the previous fall as owner Garry Herrmann had.22

The game was scheduled for 3 PM. Nearly 5,000 fans filled the grandstand and surrounded the field at 50 cents a ticket. Sporting white slacks and a blue blazer, Harding warmed up with the teams, posed for photos, and signed autographs. He took the mound for the Tailors and threw three pitches to Max Flack to open the action. The actual game followed with the Tailors reinforced by the addition of catcher Tom Daly and pitchers Speed Martin and Sweetbread Bailey from the Cubs.

Grover Cleveland Alexander pitched the first inning for the Cubs, then gave way to rookie Joe Jaeger.23 Jaeger had recently been discharged from service at Fort Sheridan and had been in just one game for the Cubs. Virtually unheard of, his name appeared in the box score of the Marion papers and others as ‘Yeager’. The enthusiastic crowd supported both squads during the game, won by the Cubs, 3-1.

Lasker’s campaign strategy worked perfectly. The voting public embraced the “Return to Normalcy” even if they were not perfectly clear what it would entail. More importantly, Harding was seen as a man of the people, in sharp contrast with his scholarly predecessor. With women eligible to vote in a national election for the first time, the vote total swelled by more than 8 million over 1916 — over 26 million votes were cast. Harding received over 16 million votes, nearly double what the Republicans had garnered in 1916. Meanwhile, Cox totaled just over 9 million, remarkably similar to the number that Wilson had in 1916. Harding’s 60.32% of the vote was by far the largest percentage to that point in U.S. history.24

Like William McKinley, Harding sought to look on as other men ran the country. For him the office of the President was a ceremonial responsibility — and baseball exemplified that. With the game a focal point of his campaign, it came as no surprise that baseball embraced Harding. Griffith announced before the inauguration that he would have a gold pass created that would allow Harding access to any home games.

The gold pass from Griffith was not the only one that Harding received. In March one of the movie theater owners in Washington followed suit. Then, on the morning of April 13, Harding was visited by a 12-man delegation of prominent black professionals and businessmen. They presented him with yet another gold pass to attend the games of the Washington Braves, an independent team unaffiliated with Rube Foster’s newly created Negro National League. Judge Robert Terrell, a noted African American jurist, invited him to throw out the first pitch. Harding accepted the pass and mentioned he would make an effort to attend. He commented to the group that he had seen “colored teams in Florida” on winter visits and he knew well the quality of ball they played.25 (This was also notable in view of longstanding rumors that Harding had some African heritage.)

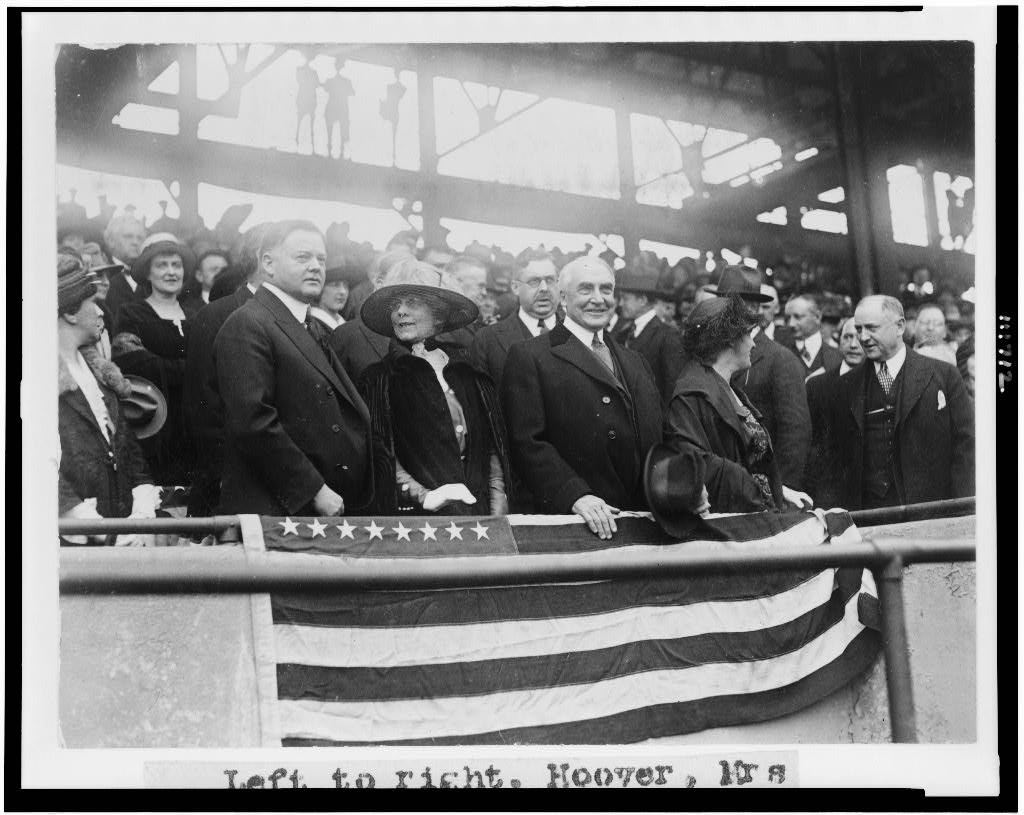

President Warren G. Harding, center, attends a Washington Senators game on April 13, 1921, at Griffith Stadium in Washington, DC. Also pictured are, from left, Secretary of Commerce (and future US President) Herbert Hoover, First Lady Florence Harding and Lou Henry Hoover, far right. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, NATIONAL PHOTO COMPANY)

Harding was in his box for the opening of the 1921 season as the Senators faced the Boston Red Sox on April 13. Following the lead established by President William Howard Taft, Harding threw out the ceremonial first pitch — to Walter Johnson. He then settled back to enjoy the action in the company of his wife, Attorney General Harry Daugherty, Clark Griffith, and Herbert Hoover (then Secretary of Commerce). Boston hurler Sad Sam Jones outdueled Johnson, 6-3. After the game, Harding gave the first-pitch ball to AL President Ban Johnson.26

Once in office there was no longer a need to distance Harding from golf or other sports that were beyond the common man of the day. He received gift sets of golf clubs and even attended the 1921 U.S. Open, where he presented the championship cup to James M. Barnes.27 Harding also attended the international military polo series and witnessed the Cuban Army team defeat Camp Humphreys, 6-3.28 But baseball remained his favorite sporting event.

Harding was in great demand and received numerous invitations to attend baseball games. His schedule seldom allowed him the chance to attend, but he would occasionally send an autographed baseball. Two events on September 30, 1921, featured charity auctions. One was Rogers Hornsby Day in St. Louis.29 The other was a benefit for Christy Mathewson staged in New York; 25,000 fans attended “Matty Day,” which featured an old-timers’ team against the New York Giants. A baseball signed by both Harding and Coolidge as well as Mathewson, Ruth, and George Kelly was auctioned for $750.30

The following year Harding attended the Senators’ Opening Day on April 12 against the Yankees. New York was without Babe Ruth, who had been suspended by Commissioner Judge Landis, for breaking rules concerning barnstorming. George Mogridge pitched and hit Washington to a 6-5 win. The Washington Times posted a copy of Harding’s clean and concise scorecard for fans to see the level of Harding’s knowledge of the game.

On May 22 Harding and his entourage attended the Senators’ game with the White Sox. Two doubles by Eddie Collins and two RBIs from Harry Hooper gave the Sox a 4-3 win. A week later Mr. and Mrs. Harding joined the Secretary of War, John W. Weeks, in Annapolis for the Army-Navy baseball game. The West Point cadets prevailed, 8-6. Harding and his wife boarded the Presidential yacht, Mayflower, following the game for the journey back to Washington.

Like any enthusiastic fan, Harding yearned to attend the World Series in 1922. His schedule did not allow him the chance to see the action, but he did follow the games on the radio. Unknown at the time was that 1922 would be his last chance to see a World Series.

Harding’s health, which had been on the decline since his days as a senator, was a major concern by 1923. He was overweight in a high-stress occupation, seldom exercised, and reportedly suffered from high blood pressure and a weak heart. His lifestyle included smoking cigars and an occasional cigarette, and chewing some tobacco. He was more likely to sponsor a late- night poker game than to go golfing.31 Despite Prohibition, he also drank whiskey in moderation.

Had Harding surrounded himself with more men like Charles Evans Hughes, his Secretary of State, Andrew Mellon in Treasury, and Hoover, his administration’s legacy might have been vastly different.32 Sadly, Harding chose to reward his friends and associates (known as the “Ohio Gang”) with various positions in government. Their excesses have been well documented. When the scandals began to break, Harding realized that it was his friends that gave him sleepless nights.

Nonetheless, his favorite sport was still an outlet for Harding. On April 3, 1923, he and Florence joined Commissioner Landis at an exhibition game in Augusta, Georgia, between the Detroit Tigers and the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League. Harding greeted Ty Cobb, Detroit manager and star, warmly. The two men had become friends before Harding’s run for president.33

President Warren G. Harding, second from right, attends a game at Yankee Stadium on April 24, 1923, in New York. Also pictured, from left, are Postmaster General Harry New, physician Charles Sawyer, businessman Albert Lasker, and New York Yankees co-owner Jacob Ruppert. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, BAIN COLLECTION)

Three weeks later, on April 24, Harding delivered a speech in New York City on the International Court. That afternoon, despite cold weather, he motored to the newly completed Yankee Stadium to watch the Senators and Yankees. The Yankees prevailed, 4-0, as Sad Sam Jones scattered five hits. Ruth highlighted the Yankees offense by slugging a home run as part of his perfect day at the plate. The home run was Ruth’s second in the stadium; he’d also homered on Opening Day. Jones’s shutout was the first in the new ballpark.

Returning to the dugout after his home run, Ruth had to pass by Harding’s box. The Babe gave a shy tip of his cap towards his smiling, appreciative president. “A few minutes later [Ruth] appeared again with a poppy. The president stood while Ruth stuck it in his button hole.”34

Harding returned to Washington after the New York trip and attended the Senators’ home opener on April 26. As usual, he threw out the first pitch, then settled back to watch the game with his wife and some cabinet members. A crowd of 22,000 watched as the Senators’ Tom Zachary scattered nine hits by the Athletics in a 2-1 triumph.

Meanwhile, political woes still loomed. In light of the scandals and other pressures, it was decided that Harding should make an extensive trip in the summer. Dubbed the “Voyage of Understanding,” the trip entailed a cross-country train ride encompassing 15 states. From Tacoma, Washington, the party would travel to Canada and then on to Alaska. Harding became the first sitting U.S. president to visit Canada.

The entourage left Washington DC on June 20. There were more members of the press and media (newsreels and movies) than members of Harding’s touring group.35 Harding sampled a true cross-section of American life as he traversed the country. The plan was for the party to eventually return to the capital on a ship by way of the Panama Canal.

On the return voyage from Alaska aboard the USS Henderson, the president suffered from exhaustion coupled with a severe case of food poisoning. Word spread rapidly around the nation that he was ill. The country had endured the final months of Woodrow Wilson’s administration when he was bedridden by a stroke. Now the presidency was again in danger. John D. Martin, president of the Southern League, ordered all the baseball games in his league to pause after the third inning on August 1, providing the fans time to say silent prayers for Harding’s recovery.36

The nation waited anxiously hoping for a positive outcome, but Harding died the next day in San Francisco. Legend has it that one of the last things he asked Florence was how the Cincinnati Reds had done that day. His body was returned to Washington, where it lay in state. Then it was transported to Marion, where he was buried on August 10. All major league games were canceled that day, as was nearly all baseball at all levels. Florence died 15 months after her husband.

Over one million people contributed to the creation of the Harding Memorial in Marion. In 1927 the bodies of Harding and his wife were transferred there. The Memorial, later dedicated by President Herbert Hoover, has belonged to the State of Ohio since 1979.37

Nearly a century after his death, Harding was back in the public eye. In 2014 letters between Harding and Carrie Phillips were unsealed and made available to the public. News media characterized Harding’s writings as steamy, salacious, and erotic. The following year genetic testing confirmed that Elizabeth Ann Britton was indeed Harding’s daughter.38 The testing also ended another long-running Harding mystery concerning his ethnicity. The DNA did not reveal any ancestors from sub-Saharan Africa.

Harding remained topical well into the 21st century. A Washington Post editorial in June 2020 highlighted his June 1921 commencement address at historically black Lincoln University in Pennsylvania as an effort to seek healing and harmony. In the wake of the Tulsa massacre, he “offered up a simple prayer: ‘God grant that, in the soberness, the fairness, and the justice of this country, we never see another spectacle like it.’”39

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello (special thanks for the Harding quotes about “the soul of the game” and the Tulsa massacre) and Norman Macht. It was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Ancestry.com provided much of the family background. Whitehouse.gov and millercenter.org (on the University of Virginia campus) were used for background information on Harding. Sherry Hall with the Harding Home in Marion provided valuable specifics and guidance. Baseball Almanac offers a collection of Harding baseball quotes.

Notes

1 https://www.google.com/search?q=babe+ruth%27s+letter+of+condolence+to+Mrs.+Harding&tbm=isch&source=iu&ictx=1&fir=DCtVEy1wgVz0FM%253A%252CO_PPqPrFj4-AEM%252C_&vet=1&usg=AI4_-kQNyd6AH6ycz8pR7pc66EPGcRzlbQ&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjE1-Last accessed May 23, 2020iLzcXpAhVGXM0KHUvFAW4Q9QEwA3oECAEQCQ#imgrc=PayGg4q71OvkfM

2 https://www.whitehousehistory.org/warren-g-harding-funeral

3 The team was called Lime Burners by the Marion Daily Mirror in 1907 and Drummers by the Marion Star that year. From 1908-11 both papers used Diggers.

4 http://www.fowlervillehistory.org/baseball/wilburcooper/biography.htmlLast accessed May 22, 2020.

5 Some sources will list the birth at Corsica which was the nearest post office.

6 “Harding’s Life Sketch,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 3, 1923: 1.

7 “Warren G. Harding Nominee for Governor,” News-Journal (Mansfield, Ohio), July 27, 1910: 1.

8 https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/warren-g-harding/Last visited May 25, 2020.

9 https://millercenter.org/president/harding/life-before-the-presidency

10 “Harding’s Life Sketch,”: 2.

11 Harding’s Life Sketch,”

12 https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p267401coll32/id/2446/Last accessed May 25, 2020.

13 Crawford County Forum (Bucyrus, Ohio), January 23, 1880: 3.

14 Harding reportedly made 5 visits to the sanitarium between 1889-1901.Last accessed June 3, 2020 https://alphaomegaalpha.org/pharos/PDFs/1997/4/Deppisch.pdf

15 http://www.firstladies.org/biographies/firstladies.aspx?biography=30

16 www.firstladies.org.

17 https://www.govtrack.us/congress/members/warren_harding/405073 The pundits here, using the Congressional journal records, credit Harding with missing 413 of 1121 roll call votes. That’s a .368 in baseball parlance, which tops Cobb’s .366 lifetime average.

18 Francis C. Richter, Casual Comment, The Sporting News, August 16, 1923: 4.

19 Peter Baker, “Test Results are in: At Last, Secret About Harding is Out,” New York Times National, August 13, 2015: A12.

20 Mark Souder, https://sabr.org/research/why-did-wrigley-lasker-and-chicago-cubs-join-presidential-campaign

21 https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/return-to-normalcy/ Last accessed June 1, 2020

22 “Team Play is What Counts,” Marion Star, September 2, 1920: 1-2.

23 “Harding Sees Cubs Defeat Home Team,” Baltimore Sun, September 3, 1920: 2.

24 Bailyn, Davis, Donald, Thomas, Wiebe, and Wood, The Great Republic (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1977), xxi.

25 “Washington Colored Baseball Association Makes Presentation,” The Bystander (Des Moines, Iowa), May 5, 1921: 1. And “Harding Given Gold Ball Pass,” Washington Herald, April 14, 1921: 7. No evidence that Harding attended a Braves’ game has surfaced.

26 “President Harding Throws out First Ball at Washington-Boston Game,” Denver Post, April 18, 1921: 11.

27 “Barnes Plays Safe Game to Make Certain of Open Title,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, July 23, 1921: 3.

28 “Cuban Poloists Win 6 to 3, as military series opens,” Washington Herald, June 19, 1921: 10.

29 “Harding has Part in Hornsby Day,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, September 16, 1921: 37.

30 “Old Time Giants Trim M’Graw’s 1921 Stars in “Matty” Benefit,” Washington Herald, October 1, 1921: 10.

31 Ludwig M. Deppisch, The Pharos, Fall, 1997. See endnote 14.

32 There were notable successes for his administration including the first budget department headed by Charles Dawes, a disarmament conference that resulted in limiting battleship production, and the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial.

33 “President Keeps Score Carefully,” Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, April 4, 1923: 1.

34 “Harding Proves Dyed-In -Wool Baseball Fan,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 25, 1923: 1.

35 https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p267401coll32/id/18105/

36 “Prayers for Harding in Southern League,” Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, April 1, 1923: 12.

37 https://www.hardinghome.org/harding-memorial/

38 Peter Baker, “DNA is Said to Solve a Mystery of Warren Harding’s Love Life,” New York Times, August 12, 2015. Accessed online at NY Times site.

39 James D. Robenalt, “The Republican President Who Called for Racial Justice in America after Tulsa Massacre,” Washington Post, June 21, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/06/21/warren-harding-tulsa-race-massacre-trump/

Full Name

Warren Gamaliel Harding

Born

November 2, 1865 at Blooming Grove, OH (US)

Died

August 2, 1923 at San Francisco, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.