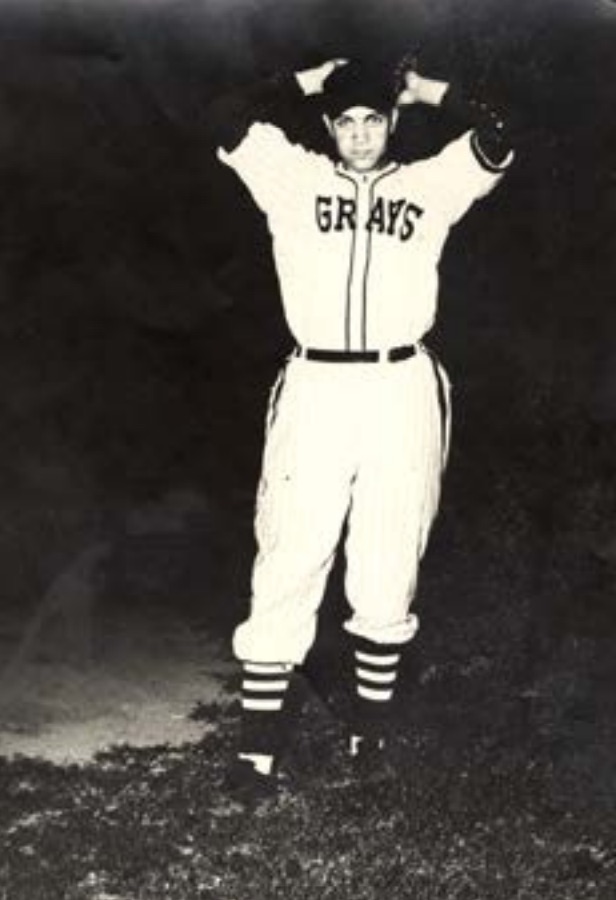

Wilmer Fields

Josh Gibson has often been called “the black Babe Ruth” since he, like the Sultan of Swat, was his league’s most-feared home run hitter, but Wilmer Fields – Gibson’s teammate during four of his seasons with the Homestead Grays – had much more in common with the Babe than Gibson did. On the surface, this truth is not readily apparent; in fact, they initially appear to be polar opposites. Ruth’s parents abandoned him to an orphanage/reform school, whereas Fields grew up in a loving home; Ruth’s reckless hedonism contrasted with Fields’ gentler, Christian demeanor; and Ruth became the savior of major-league baseball while Fields never played in a single major-league game. However, a look at their career paths and statistics shows that they were two of a kind: star players with the rare ability to pitch and to hit with equal acumen.1

Josh Gibson has often been called “the black Babe Ruth” since he, like the Sultan of Swat, was his league’s most-feared home run hitter, but Wilmer Fields – Gibson’s teammate during four of his seasons with the Homestead Grays – had much more in common with the Babe than Gibson did. On the surface, this truth is not readily apparent; in fact, they initially appear to be polar opposites. Ruth’s parents abandoned him to an orphanage/reform school, whereas Fields grew up in a loving home; Ruth’s reckless hedonism contrasted with Fields’ gentler, Christian demeanor; and Ruth became the savior of major-league baseball while Fields never played in a single major-league game. However, a look at their career paths and statistics shows that they were two of a kind: star players with the rare ability to pitch and to hit with equal acumen.1

As a pitcher for the Boston Red Sox, Ruth was a two-time 20-game winner and led the American League with a 1.75 ERA in 1916. He had a 94-46 career record (89-46 with Boston), and he also set a record by pitching 29⅔ consecutive scoreless innings in World Series play.2 After he was sold to the New York Yankees and converted into an outfielder, he became baseball’s first true power hitter, finishing his career with a batting average of .342 and smashing the total of 714 home runs and 2,214 RBIs for which he is best known. Ruth led the American League in home runs 12 times and won a batting title when he hit .378 in 1924. Surprisingly, he won only one Most Valuable Player Award, in 1923.3 World Series championships, on the other hand, were plentiful for the Babe as he helped to lead his teams to seven titles (three with Boston and four with New York).

In comparison, Fields notched a 102-26 record in eight seasons as a pitcher for the Homestead Grays (1940-42, 1946-50). In addition to his Negro League totals, he posted career won-lost marks of 38-7 in Canada, 11-1 with the semipro Fort Wayne Allen Dairymen, 28-15 in Puerto Rico, 6-2 in Venezuela, and 5-2 in the Dominican Republic for a composite pitching record of 190-53. Though he was primarily a pitcher with the Grays, Fields also learned to play third base and the outfield, and there was no fall-off in his performance at the plate or in the field. He had a .425 batting average for the Oshawa (Ontario) Merchants in 1955 and, in his final season of 1958, hit .392 as an outfielder for the Mexico City Red Devils. Fields won a total of six MVP awards in four different leagues: the Puerto Rican Winter League, the Intercounty (Canada) League (three times), the Venezuelan Winter League, and the Colombian Winter League. He also won the Negro League World Series with Homestead in 1948, and he helped lead Fort Wayne, representing the United States, to the Global World Series title in 1956. It could be argued that the only thing that Fields does not yet have in common with Ruth as a player is membership in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Wilmer Leon Fields was born on August 2, 1922, in Manassas, Virginia, to Albert and Mabel Fields. He was one of five children, along with his older brothers Morris, Marvin, and Oliver, and his younger sister, Evelyn. Albert Fields made a living by working in a lumber yard for 33 years, and he saved enough money to send all five of his children to college; their finances were helped by the small family farm they tended, which ensured that there was always plenty of food on their table.

Fields’s earliest baseball experiences involved playing against his family and neighbors. He credited sibling rivalry with helping him to hone his skills from an early age, saying, “I had three older brothers that I used to compete against every day … and I tried to play as good as they were playing.”4 Though he already was aware that the limitations imposed upon blacks in segregated America would keep him out of the major leagues, he also knew about the Negro Leagues and he confessed that, by the age of 8, “I used to get on my knees and pray to God to give me the ability to play professional black baseball.”5 Fields evinced natural talent, and at the age of 10 he and his father played in a game together on the Manassas town team, an experience he described in his autobiography, My Life in the Negro Leagues, as one of his most cherished memories.

Fields played on his high school’s baseball team, though their games were few, and became a regular member of the town team. When the Manassas team disbanded before his senior year, all four Fields brothers ended up playing for the Fairfax, Virginia, team. Fairfax’s management arranged a tryout with the Homestead Grays for Wilmer, and he pitched well enough in a game against a semipro team that he was offered a contract. At the age of 17, he left Manassas to embark upon his career in professional Negro baseball. Mabel Fields sent her son into the world with a Bible to strengthen him. Fields took the message to heart throughout his life and admitted, during that first year, “I even played baseball with that Bible. I’d wrap it up in a sock and stick it in my pants pocket.”6

The Grays used Fields sparingly in 1940, as a youngster who was still learning the ropes, and he put up a 2-1 record for Homestead’s fourth consecutive Negro National League title squad. That fall Fields was offered a football scholarship, and he enrolled at the Virginia State College for Negroes in Ettrick, Virginia, where he played quarterback.7 During his freshman year, he was not allowed to participate in conference games because he had already played professional ball, even though it had been baseball rather than football; Fields was happy that the rule was changed by his sophomore season. At the end of his freshman year, Fields received a surprise – and his classmates’ admiration – in the form of a package that contained a reward for being a member of the Grays: It was a baseball-shaped radio with “National Negro World Champions 1940” inscribed on it.8 Initially, he continued to study and to play football during the Grays’ offseason, but he ended up completing only his first two years of college as baseball stardom beckoned.

Having shown his mettle, Fields became a regular member of Homestead’s starting rotation in 1941. He had a 13-5 record that season, which he followed up with a 15-3 mark in 1942 as the Grays won the NNL championship again in both years. Though Homestead was a suburb of Pittsburgh, the Grays actually had two homes: They played most of their Pittsburgh games at Forbes Field and they played the remainder of their “home” games at Griffith Stadium in Washington. 9 Since they were at home in two cities, played league road games, and were in demand for exhibition games all over the country, the Grays were most often on the go. The constant bus travel helped to mold the players into a close-knit squad and combined with the talent of the team’s players to turn them into the Negro Leagues’ pre-eminent juggernaut of the 1930s and 1940s.

Travel did have its downside for black players in the Jim Crow-era United States as the team never could be sure where they might be able to buy food or gas for their bus. Fields had a light enough complexion that he could pass for a white man – Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe jokingly called him “the man who integrated the Homestead Grays”10 – and he retold one particular incident that occurred on the road:

“We were traveling through Mississippi. … We stopped at a general store. … I went in there and there was a bar there and about 13 men sitting at the bar. I told the manager I wanted a couple of sandwiches. … I looked up and here come R.T. [pitcher Robert Walker] walking through the door. … and [he] said, ‘Hey, Chinky! Get me a couple of sandwiches!’ The manager looked at me and looked at him. He said, ‘You with him?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I’m with him.’ He said, ‘Get out of here.’”11

Fields’ nickname, Chinky, had its origins in the Grays’ camaraderie that he valued so much. He explained that a “chinkpin” was a brown and yellow-colored nut with a fuzzy covering and that he was wearing a black and gray jacket at practice one day when future Hall of Famer Buck Leonard told him, “Fields, you look just like a ‘Chinkypin.’”12 The nickname stuck and was even passed down to Fields’ oldest son, Marvin.

Fields had become a star with the Grays, but World War II put his career on hold when he was drafted into the US Army in 1943. He went through basic and technical training at Camp Plauche, Louisiana, before being sent to New York, from where he was shipped to Liverpool, England.13 Fields was fortunate not to be involved in combat, but he did become so seriously ill at one point that he was sent to Paris to recover in a hospital. A short time after Fields recovered, a first sergeant put together a baseball game on a former battlefield and was so impressed by Fields that he wanted him to join his company that was headed for Japan now that the war in Europe had ended. Good fortune again smiled upon Fields as Japan surrendered before he could be shipped out to the Pacific.

After he returned stateside, Fields completed his military service at Camp Plauche. While in Louisiana for the second time, he met his future wife, Audrey Roche, in New Orleans. They were married at Gretna, Louisiana, in May 1946 before Fields left for Fort Meade, Maryland, to be discharged from the Army. They would go on to raise three children – son Marvin, daughter Maridel, and son Wilmer Jr. (Billy) – over the course of a marriage that spanned 58 years.

During Fields’s absence, the Homestead Grays had won three additional NNL titles and had defeated the Birmingham Black Barons in both the 1943 and 1944 Negro League World Series. Fields rejoined the team in 1946 and pitched as though he had never been gone at all – he had a 16-1 record – though the team failed to win the NNL. In his final start that season, an exhibition game against a barnstorming team, Fields dueled against Johnny Vander Meer, who was best known for pitching consecutive no-hitters for the Cincinnati Reds in 1938. In a low-hit, high-strikeout game by both of the pitchers, Vander Meer and his squad prevailed by a 1-0 score. In spite of this tough end to the 1946 season, Fields had pitched so well during the year that he had received the first of six offers from major-league teams that desired his services. The Brooklyn Dodgers had offered Fields a contract to play for the Montreal Royals, their Triple-A affiliate, for which Jackie Robinson played during 1946, his first season in Organized Baseball. Fields turned down the offer.14

Fields’s talent continued to be noticed and, as the integration of baseball progressed, he received numerous contract offers; however, he turned them all down. Over the next several years, he declined offers from the New York Yankees (1948), Washington Senators (1949), Philadelphia Athletics (1951), St. Louis Browns (1952), and Detroit Tigers (1955). In his autobiography, Fields provided the rationale for what seemed to many people to be a peculiar decision. He explained that he was earning more money by playing in the Negro Leagues and, later, Canada and the Latin winter leagues than most major-league ballplayers were paid; it simply made more sense for him to earn as much money as he could to support his family. His son Billy Fields said another factor was that he was more comfortable having his family travel with him in Canada, as well as the Latin American countries in which he played, than throughout the still-segregated United States.15

Instead of joining a team in Organized Baseball, Fields remained with the Grays and posted a 56-16 record from 1947 through 1950. The 1948 season was his most memorable with Homestead as he was a member of the franchise’s last championship squad. The team still had players like Sam Bankhead, Luke Easter, and Buck Leonard, and Fields went 13-5 during the season. He was selected to play in the annual East-West All-Star Game for the first time and took part in the August 22 contest at Comiskey Park in Chicago.16 Fields pitched to his usual standard in front of the 42,099 fans who had gathered to witness Negro baseball’s most popular annual event. According to the Pittsburgh Courier’s Bill Nunn, “The best form shown by an Eastern pitcher was that of Wilbur [Wilmer] Fields, the Grays’ big right hander, who didn’t allow a run in the three innings he worked.”17 Fields had done his part – he had allowed one hit, issued one walk, and struck out two batters from the fourth through sixth innings – but the West had prevailed 3-0.18 Though pitching in the All-Star Game had been an exciting honor, Fields’s biggest game of the 1948 season was yet to come in the Negro League World Series.

First, though, the second-half NNL champion Grays had to overcome the first-half champion Baltimore Elite Giants, which they did in convincing – and somewhat bizarre – fashion. After winning the first two games, the Grays turned a 4-4 tie into a 7-4 lead in top of the ninth inning of Game Three on September 17. In the process, the city of Baltimore’s 11:15 P.M. curfew passed, and the Elite Giants – believing that the entire ninth inning would have to be replayed if it went past 11:15 – began to stall the game by refusing to get Grays batters out.19 At first, their tactic appeared to work as Game Three was indeed suspended and, before it was concluded, Game Four – an 11-3 Baltimore win – was played on September 19.

On September 20 the Grays pulled off the oddity of a three-game sweep in spite of a Game Four loss, owing to a decision made by the NNL’s president, Rev. John H. Johnson. He applied a league rule that said any inning begun before 11:00 P.M. had to be completed (even if it lasted past the 11:15 P.M. curfew) and “ruled [the Elite Giants’ stalling] was unsportsmanlike and therefore grounds for the game to be forfeited to the Grays, 9-0.”20

Now that the Grays had advanced to the Negro League World Series to face their old adversaries, the Birmingham Black Barons, they encountered a new problem: They were unable to use either of their home fields – Forbes Field or Griffith Stadium – because both venues were occupied by their major-league owners, the Pittsburgh Pirates and Washington Senators. Thus, Game One, a Grays’ victory, was played in Kansas City on September 26 before the series shifted to Birmingham.21

Fields missed Homestead’s Game Two win and Game Three loss in Birmingham as he had driven to Virginia to pick up his family so that he could take them to see his Game Four start in New Orleans on October 3. He drove for 27 hours, taking only a half-hour nap along the way, in order to make it to Game Four on time.22 Former Negro League pitcher William “Dizzy” Dismukes, covering the game for the Chicago Defender, reported that the Grays “hammered everything the four Birmingham Black Barons pitchers dished up … and slaughtered the Negro American League champions.”23 Fields, however, was masterful for the Grays in the 14-1 romp that gave Homestead a 3-to-1 lead in the series. He recalled, “I was in such bad shape I was shaking. My ball didn’t run or move like other people’s balls move, but that day I was in such bad shape it was moving – just like a slider.”24 Afterward, Birmingham’s Artie Wilson said to Fields, “I didn’t know you could pitch like that,” to which he replied, “I didn’t know either.”25

Two days later, back in Birmingham, Fields relieved R.T. Walker late in Game Five. The Grays then scored four runs in the 10th inning to win the game, 10-6, and clinched the title over the Black Barons and their budding young star, 17-year-old Willie Mays. Homestead’s triumph was the last glorious gasp of the rapidly declining Negro Leagues. Coverage of the series had been sparse, as even the black press focused more on the roles Larry Doby and Satchel Paige were playing for the Cleveland Indians in the major-league World Series. Attendance at the games had also been low. Fields explained, “We agreed to play it down South in AA stadiums instead of our usual major league parks. We only drew about four or five thousand spectators to these ballparks and that was a disaster.”26

The integration of Organized Baseball had sent the Negro Leagues into decline as their member teams began to lose most of their best players to major- and minor-league baseball. The NNL folded after the 1948 season, meaning that the days of Negro League World Series play were at an end. The Grays joined the Negro American Association in 1949, played as an independent club in 1950, and then disbanded in May 1951.

The demise of the Grays meant that Fields would have to play elsewhere and, eschewing the major leagues, he turned to Latin America and Canada. He had already been playing winter-league ball in Puerto Rico since the 1947-48 season; he found the commonwealth’s avid fans and lack of segregation greatly to his liking. After Fields and his wife, Audrey, had survived their first-ever airplane trip to San Juan, he settled right in. He was named Player of the Week twice in 1947-48 and reporters dubbed him “Wilmer Fields the Great.”27

Fields returned to Puerto Rico for the 1948-49 season, now playing for Mayaguez, and won the first of his MVP awards. He was 10-4 on the mound and batted .332 with 11 home runs and 88 RBIs. He also played in the first Caribbean World Series, in 1949, as Mayaguez represented Puerto Rico in a four-country field that also included Venezuela, Cuba, and Panama. Cuba’s heavily favored Almendares Alacranes (Scorpions) won the inaugural series, which was played in their home country. Chuck Connors, who became famous as TV’s The Rifleman in the 1950s, was a member of the Cuban team; he batted .409 with five RBIs and five runs scored, and tied for the series lead with four stolen bases. Though Connors had a great series, he may have had an off game when Cuba played against Puerto Rico since Fields observed, “He chose the right profession when he decided on acting.”28

Fields was back in Mayaguez for the 1949-50 season, at the end of which he played in the second Caribbean World Series; this time the series was played in Puerto Rico and was won by Panama’s Carta Vieja Yankees. Fields’ playing days in Puerto Rico came to an abrupt end during the 1950-51 season. The Puerto Rican Nationalist Party had begun a series of violent uprisings on October 30, as a push for Puerto Rico to gain independence from the United States, and the Fields family made its way to San Juan and off the island as quickly as possible. He finished the 1950-51 season with Maracaibo in the Venezuelan League.

After the winter season, Fields became one of the many former Negro League players to head north to Canada. In 1951, he played for the Brantford (Ontario) Red Sox of the Intercounty League, where he won his second career MVP award after compiling a 9-1 record and a .382 batting average, and leading the league in hits, home runs, and RBIs.29 Fields enjoyed his time in Canada and considered it a second home thanks to the wholehearted acceptance he and his family felt while living there.

In order to earn a living as a professional baseball player, Fields had to play year-round, so he returned to Venezuela for the 1951-52 winter season. He played for Caracas, where one of his teammates was Chicago White Sox shortstop Chico Carrasquel, who was only the third Venezuelan major leaguer; his uncle Alex Carrasquel, who had pitched for the Washington Senators in1939, had been the first. Fields did not pitch for Caracas, but he won his third MVP award by batting .348 with 8 homers and 45 RBIs. He played in his third and final Caribbean Series for Caracas in 1952, but Cuba’s Habana Leones (Lions) won the championship in Panama that year.

In the spring of 1952 Fields returned to Canada under what he considered to be less than favorable circumstances. He still loved the country, but he was not happy that he was forced to play for the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League. In 1951 he had been contacted by Jack Kent Cooke, Toronto’s new owner, who would later gain greater notoriety as the owner of the NFL’s Washington Redskins. Cooke had not been able to sign Fields at that time, but he finally made Fields a compelling offer while he was in Caracas in 1952: A $5,000 signing bonus, a major-league contract, and the assurance that Cooke would pay for Audrey Fields to travel on all road trips. Fields accepted Cooke’s offer by way of a telegram, not knowing that such a response constituted a binding contract. At the conclusion of the Venezuelan season, Fields had a change of heart about playing for Cooke, but Cooke would not release him from his contract.

In addition to the fact that he was unhappy at having to play for Toronto, Fields also had an unpleasant racial incident occur while he was with the team for spring training in Florida. Though this was 1952 and baseball was in the midst of integration, tolerance for blacks in the South was still low, and he unintentionally angered a white clubhouse attendant by calling him “Horse” while asking for a chair; according to Fields, “When I was playing in the black leagues, we used to call each other Horse.”30 The attendant never brought a chair; the next time Fields saw him, as he exited the clubhouse, the man was sitting on his pickup truck and holding a shotgun. What happened next made a lasting impression upon Fields, and he often cited this incident as an example of what black players had to endure:

“I was about 25 or 30 yards away from him. There were some wires I had to go under and some blackbirds were setting on ’em. Man, he blasted away and knocked one of the blackbirds off of there and it fell down in front of me. I just kept walking. … I never told anybody for a long time ’cause if I told my wife, she’d say, ‘Let’s go home.’”31

Fields did not go home. He fulfilled his obligation to Cooke, but his lone season with the Triple-A Maple Leafs was interrupted for six weeks when he suffered a broken wrist; he finished the 1952 campaign in Toronto with a .291 batting average.

After that, Fields bounced back and forth between Canada and Latin America over the next few seasons. He played the 1952-53 winter season in Venezuela, but he moved to the Dominican Republic in 1953-54. He played three games a week for San Pedro de Macoris for which he received $3,000 per month in salary and expenses, which constituted the highest pay of his baseball career.32 After that, Fields spent two seasons in Colombia, where he won the sixth and final league MVP award of his career in the 1955-56 season. Fields was well-respected by every owner he played for – with the obvious exception of Cooke – and he was offered the managing job in Colombia after his second season in the country. In an example of the far-reaching effects of discrimination, Fields turned down the job because, as the only black American on the team, he was concerned that “there might have been a letdown from some of the other imports” as he recalled “some of the white imports not appreciating us eating at the same table as their families.”33

In between his Latin excursions, Fields spent the 1953-55 summer seasons in Canada, though he was out from under his contract with Cooke’s Toronto team. He spent 1953 with the Brandon Greys of the Manitoba-Dakota League, where he batted .356. On July 24 he hit a grand slam and totaled six RBIs in leading the Greys to a 13-5 victory over the Winnipeg Royals.34 In 1954 Fields returned to Brantford, where he pitched his way to a 9-3 record while hitting at a .379 clip. The following season, he played for the Oshawa Merchants and improved his record to 8-0 while raising his batting average to .425.35 As a true double-threat on the mound and at the plate, he again won the Intercounty League MVP award in both the 1954 and 1955 seasons.

On the heels of his final two successful seasons in Canada, Fields briefly played with the Indianapolis Clowns in 1956. The Baltimore Afro-American heralded his signing that May, proclaiming, “Fields, former star of the Homestead Grays, is still in his late twenties, one of the most dangerous and best hitters to come along since the days of Josh Gibson.”36 The Afro-American had shaved some years off Fields’ age – he was 33 now – and had failed to note that he had been Gibson’s teammate at one time. The Clowns were “not a high-quality ballclub” anymore, and it was obvious that little attention was paid to the vestiges of the Negro Leagues.37 It seemed odd that Fields would join Indianapolis at all since, in the past, many Negro League players had taken umbrage at the team’s clowning, believing that it demeaned all of Negro baseball. His time with the Clowns, now primarily a barnstorming team, was brief and merited only one mention in his autobiography in which he recalled that the team’s travel accommodations were so poor that he had slept in a YMCA once.

Fields soon joined a different franchise in Indiana, the Fort Wayne Allen Dairymen of the semipro Michigan-Indiana League. Fort Wayne had participated in numerous Global World Series, organized by the National Baseball Congress (NBC), and had won four consecutive championships from 1947 to 1950; with Fields on the team, they would win one more, in 1956.38 Fort Wayne first had to win the US National Semipro Tournament in Wichita, Kansas, since the winner would represent the United States at the Global World Series in Milwaukee. Though the Texas Alpine Cowboys, who had the Brooklyn Dodgers’ 1955 World Series MVP Johnny Podres on their team, were the favorites, the Allen Dairymen emerged as tournament champions.39

In Milwaukee, Fort Wayne made it to the championship game, against Hawaii.40 In the first inning Fields hit a single to drive in his teammate John Kennedy for a quick 1-0 lead. It turned out to be the only run the Dairymen needed, though they added another in the seventh, as Pete Olsen spun a shutout to clinch the title.41 Afterward, Fields was named to the tournament’s “All-World” team.42

In 1957 Fields returned to Fort Wayne and again led the Dairymen to the NBC’s tournament final in Wichita, but this time around they lost to the Sinton (Texas) Oilers; though he had played for the runner-up, Fields still was named the tourney MVP. He then played for the Sinton squad in the Global World Series as the United States tried to defend its championship in what was billed as “non-professional baseball’s biggest tournament.”43 Fields and Clint Hartung, a former New York Giants pitcher and outfielder from 1947 to 1952, were the stars for the US team. In the first round, against Colombia, Hartung hit a 10th-inning RBI single that Fields followed with a two-run homer to give the US team a 6-3 victory.44 Though the Oilers had advanced, they would not secure a third consecutive championship for the United States. In fact, after suffering their first loss, against Japan, they “suffered the ignominy of the mercy rule as their game [against Canada] was shortened to seven innings by the score of 8-0.”45 It was small consolation that Fields, Hartung, and two of their teammates were named to the all-tournament team.

Though Fields had still performed well, his career was nearing its end. He played for St. Joes in the Michigan League in 1957, spent part of 1958 with the Yankton Terrys of South Dakota’s Basin League,46 and finished 1958 with the Mexico City Red Devils. Though he had batted .392 for Mexico City, he was now 36 years old and chose to retire from baseball.

Fields settled his family in his hometown of Manassas; they moved into a ranch house that was only two doors down from the house in which he grew up and where he learned to play baseball.47 Initially, he worked as a bricklayer’s helper; however, he soon found more satisfying work as a counselor for alcoholics for the District of Columbia Department of Corrections. Fields also worked at Lorton Reformatory, a D.C. prison in nearby Virginia, where he organized baseball games between inmates and students from the Prince William County School District.48

Family was of greatest importance to Fields throughout his life, and he coached his son Billy’s youth baseball teams in the 1970s. In fact, Billy appeared set to follow in his father’s footsteps when he unexpectedly received an offer from the Detroit Tigers as he prepared to enter college in 1978. According to Billy Fields, the Tigers offered to pay his college expenses and he would have attended their Florida training camp in the summers until he graduated, whereupon he would have been assigned to the minor leagues. As it turned out, however, the Tigers wanted to convert Billy from a pitcher into a first baseman or outfielder, so he chose to accept a basketball scholarship to Providence College instead.49

In time, the Negro Leagues began to be rediscovered by researchers and fans alike, and Fields appeared in various ceremonies at which the Homestead Grays were honored. On September 10, 1988, he was one of 11 Negro League players honored by the Pittsburgh Pirates who commemorated the 40th anniversary of the Grays’ last championship prior to that evening’s game. Five years later, on August 29, 1993, Fields was in attendance when the Pirates raised banners to honor both the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays; the flags would continue to fly alongside the Pirates’ own championship banners at Three Rivers Stadium. In between the two Pittsburgh ceremonies, Fields attended a Negro League players’ reunion in August 1991 that was hosted by the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. He enjoyed the occasion immensely, joking that “It’s always interesting when you go to a reunion and you can talk with all the guys, and nobody can tell a lie.”50

Fields became such a ubiquitous presence at Negro League events that his peers elected him president of the Negro League Baseball Players Association in 1994. Though he had not desired to serve as the organization’s leader, after he received 67 percent of the vote, he said, “I couldn’t turn my back on those people. … I’m working every day – almost – on projects, trying to get something started.”51 Fields promoted the legacy of the Negro Leagues wherever he could, primarily through lectures at schools and community events. He also worked tirelessly to try to gain medical and pension benefits for former Negro League players, a venture at which he had some measure of success.52 A short time prior to Fields’ death, Commissioner Bud Selig had announced that Major League Baseball would pay in excess of $1 million in pension money to 27 former Negro Leaguers.53

Wilmer Fields died on June 4, 2004, in Manassas.54 His legacy is secure, yet he is not one of the Negro League legends enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. When Negro League historian Brent Kelley asked Fields point-blank if he thought he should be in the Hall, Fields answered:

“If the rest of the black ballplayers are in, I should be. Yes, they were outstanding players in their positions, but I played three positions. … See, any time you play over ten years in Latin American countries in winter time, somebody gave you respect. You had to do something here in the States in order for them to notice you so that you could play winter baseball.”55

In light of Fields’ superlative career, it seems reasonable to conclude that he has not been enshrined in the Hall of Fame due to arguments that incorporate such logic as 1) Fields’ feats are not the equal of Ruth’s in scope because he never played in the major leagues, and 2) his accomplishments do not parallel Gibson’s because, unlike Gibson, he did not play the vast majority of his Grays’ career during the Negro Leagues’ heyday. Nevertheless, it is a fact that Fields competed against top black, white, and Latin competition at various times, and he excelled wherever he played. Though Fields believed he belonged in the Hall of Fame, he was not bitter about his exclusion, saying, “I asked the Lord for something [his baseball career] and He gave it to me. I’m thankful.”56

In his foreword to Fields’ autobiography, Negro League historian John Holway cited a story Fields told him about a home run he hit for Mexico City in 1958, his final season. Fields claimed to have hit a ball out of the Red Devils’ stadium farther than anyone before him and ended his tale by telling Holway, “I wish you had seen that one.”57 Fields is a member of other Halls of Fame in places where people did see him. In 2001 he became only the third American player – following Willard Brown and George Brunet – inducted into the Caribbean Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2006 he was posthumously selected as an inaugural member of the Black Hockey and Sports Hall of Fame in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada. Perhaps someday a plaque depicting Fields will be seen in Cooperstown alongside those of Ruth and Gibson.

Author’s Note:

There are a number of conflicting accounts in regard to certain events in Fields’s life and his statistical record. One problem in particular is that statistics for Negro League players are notorious for being incomplete or, at other times, inaccurate. Every effort was made to consult as many different sources as possible in order to reconcile the conflicting events and statistical records and to arrive at an accurate representation of both; nevertheless, Fields’s career record may well be incomplete. The difficulty in attempting to determine what happened 60 or more years ago is best exemplified by the fact that even Wilmer Fields himself made certain errors as he tried to recall all of his life’s experiences while writing his autobiography in 1992; in one instance, he stated that he had played for Brantford in 1955, though game recaps and box scores clearly indicate that he had played for Oshawa. (Both teams were in the Intercounty League.) The author welcomes any and all corrections that may result from further information coming to light through future research. Frankly, it is to be hoped that more information about the Negro Leagues and their players will be rescued from obscurity to provide a fuller portrait of the past.

Sources

The author wishes to express his gratitude to Billy Fields for taking the time to discuss his father’s life and career and for providing valuable artifacts in the form of scanned photos and documents.

In addition to the sources provided in the Notes, the author also consulted the following:

Baseball-Reference.com (baseball-reference.com).

Center for Negro League Baseball Research (cnlbr.org).

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, The Mexican League: Comprehensive Player Statistics, 1937-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2002).

Clark, Dick, and Larry Lester. The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: SABR, 1994).

Klima. John. Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2009).

Lanctot, Neil. Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

Lester, Larry. “Wilmer Leon Fields: The Gentle Giant,” thenationalpastimemuseum.com/article/wilmer-leon-fields-gentle-giant, accessed March 7, 2016.

McNary, Kyle. Black Baseball: A History of African-Americans & the National Game (New York: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2003).

Negro League Baseball Players Association (nlbpa.com).

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum eMuseum, “Wilmer Fields,” coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/fields.html, accessed March 7, 2016.

Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970).

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Snyder, Brad. Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball (Chicago: McGraw Hill, 2003).

Western Canada Baseball (attheplate.com).

Notes

1 Two additional Negro League players bear mention here since they also excelled both on the mound and in the field: Martin Dihigo (1905-71) and Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe (1902-2005). Dihigo, a Cuban, was primarily a pitcher over the course of his career from 1923 to 1945, but he also played all of the infield and outfield positions and wielded a dangerous bat; he played in the Negro, Cuban, and Mexican Leagues and was inducted posthumously into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977. Radcliffe, whose career spanned the years 1928 to 1950, was a pitcher, catcher, and later also a manager; he earned his nickname, Double Duty, because he often pitched the first game of doubleheaders and caught the second game. Dihigo, Radcliffe, and Wilmer Fields never played in the major leagues, but all three players were dual threats, the likes of which have rarely been seen in any league. Though Dihigo is rightfully enshrined in the Hall of Fame, as of 2016, Radcliffe and Fields have not been inducted.

2 New York Yankees pitcher Whitey Ford broke Ruth’s record in 1961 and extended his scoreless streak in World Series play to 33⅔ innings in the 1962 World Series.

3 There was no American League MVP award in 1929, though Ruth would have been a top candidate if there had been: He batted .345 with a league-leading 46 home runs and 154 RBIs.

4 Brent Kelley, Voices From the Negro Leagues: Conversations With 52 Baseball Standouts (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998), 107.

5 Ibid.

6 Wilmer Fields, My Life in the Negro Leagues: An Autobiography, reissue with a new introduction (McLean, Virginia: Miniver Press, 2013), 3.

7 The institution is now named Virginia State University.

8 Fields, 7.

9 Since the Grays played half of their home schedule at Griffith Stadium, they also became known as the Washington Homestead Grays.

10 John Holway, “Foreword” in Fields’s My Life in the Negro Leagues, x.

11 Kelley, 106.

12 Fields, 20. Fields was also known by the nickname Red; however, it is clear from his autobiography that the nickname he was best known by was Chinky. It should also be noted that the name of the tree that produces the nuts Fields described is the chinquapin; the pronunciations chinkpin and chinkypin are forms of dialect.

13 Camp Plauche was also known by the name Camp Harahan.

14 Former Homestead Grays ace John Wright, one of Fields’s teammates, became the second black player signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1946. He had a brief stint with the Montreal Royals, where he was Jackie Robinson’s roommate; however, he made only two appearances with the team before he was sent to Three Rivers of the Canadian-American League. He returned to the Grays for the 1947 and 1948 seasons. See James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 883.

15 Wilmer L. (Billy) Fields Jr., telephone interview with the author, June 5, 2016.

16 The second East-West All-Star Game was played on August 24, 1948, at Yankee Stadium. Fields did not play in the second game.

17 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 309.

18 Lester, 313.

19 Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 2.

20 Ibid.

21 Some sources erroneously list Memphis, Tennessee, as the site for Game Two. According to the Birmingham Age Herald, Game Two was played at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field. (This information was provided by Dr. Richard J. Puerzer, a SABR member and researcher/author, in an email to this author dated May 25, 2016). John Klima, author of Willie’s Boys, stated that he had discussed game articles with Rev. Bill Greason, the Birmingham Black Barons pitcher who won Game Three, and that he also had confirmed that Game Two took place in Birmingham (per an email from Klima to this author dated December 17, 2015).

22 Kelley, 103.

23 William Dismukes, “Homestead Grays Swamp Black Barons, 14-1,” Chicago Defender, October 9, 1948.

24 Kelley, 103.

25 Ibid.

26 Christopher D. Fullerton, Every Other Sunday (Birmingham: R. Boozer Press, 1999), 90.

27 Fields, 33.

28 Fields, 36.

29 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2009), 65.

30 Kelley, 106.

31 Ibid. Fields recounted the same episode in his autobiography, albeit with less detail.

32 Fields, 43.

33 Fields, 59.

34 Swanton and Mah, 66. Some sources list Fields as playing for Brantford in 1953, but Swanton’s and Mah’s research shows that he played for Brandon; perhaps the similarity of the city names has created the common error.

35 Ibid. Fields, after the passage of almost four decades of time, wrote that he had played for Brantford in 1955; however, Swanton and Mah again cite game capsules in their book that show he had been with Oshawa in the Intercounty League.

36 “Clowns, Yanks Set Mark; Wilmer Fields to Return,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 15, 1956.

37 Riley, 407.

38 The earlier Fort Wayne championship teams were named the Capeharts.

39 Bob Buege, “Global World Series: 1955-57,” sabr.org/research/global-world-series-1955-57, accessed March 7, 2016.

40 To eliminate any confusion, it must be remembered that Hawaii did not become a state until August 21, 1959.

41 Ibid.

42 Swanton and Mah, 66.

43 “Hartung Ace in U.S. Win,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 14, 1957.

44 Ibid.

45 Buege, “Global World Series: 1955-57.”

46 Swanton and Mah, 66. This well-researched book is the only source that lists Fields with the Yankton team.

47 Peter Vilbig, “Cooperstown to Recognize Black Players,” Hendersonville (North Carolina) Times News, August 5, 1991.

48 Adam Bernstein, “Wilmer Fields, Negro Leagues Player and D.C. Counselor, Dies at 81,” Washington Post, June 21, 2004. It should be noted that Manassas, Fields’ hometown, is the county seat of Prince William County, which is why Fields chose youths from that area to play in the baseball games he organized.

49 Billy Fields interview. Billy had been completely unaware that he was being scouted until the evening that the Detroit Tigers scout, whose name he no longer remembers, came to visit the Fields home to make the team’s offer. Though he was worried that his father might be disappointed by his decision not to pursue a potential baseball career, Wilmer Sr. was happy that Billy was getting a college education, no matter which sport he chose to play.

50 Vilbig, “Cooperstown to Recognize Black Players.”

51 Kelley, 107.

52 Billy Fields noted that his father often received calls from individuals who claimed to have played for one Negro League team or another at one time or another, and Wilmer Sr. then had to undertake the task of attempting to verify the legitimacy of the claim. Fields wanted every player who was entitled to benefits to get them, but he also wanted to be sure that no impostors received undue compensation.

53 Lacy Lusk, “Wilmer Fields: A Legend of Stability,” Manassas Journal Messenger, June 19, 2004. Lusk also pointed out that, previously, pension money had been given only to Negro Leaguers who had spent at least one day in the major leagues. Of course, this stipulation had been impossible for Negro Leaguers to meet prior to Jackie Robinson’s breaking the color barrier in 1947.

54 Fields had been preceded in death by his daughter, Maridel, in 1996. His son Marvin died in 2015. As of the writing of this biography in June 2016, he is still survived by his widow, Audrey, and son, Billy.

55 Kelley, 103-4.

56 Kelley, 108.

57 Holway, “Foreword,” xii.

Full Name

Wilmer Leon Fields

Born

August 2, 1922 at Manassas, VA (US)

Died

June 4, 2004 at Manassas, VA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.