Brooklyn Players’ League team ownership history

This article was written by John G. Zinn

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

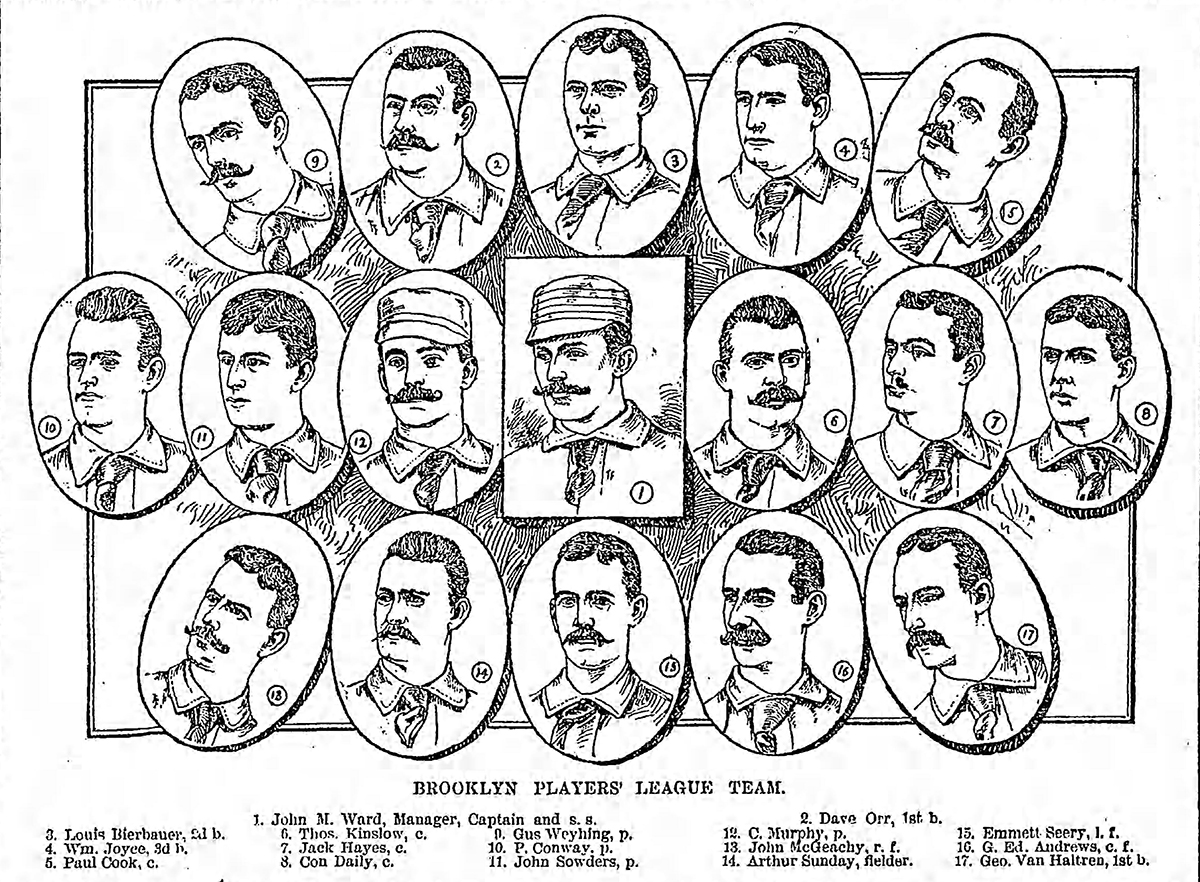

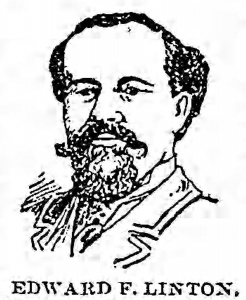

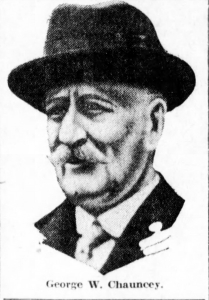

Shortly before Christmas of 1889, about 20 men gathered at New York City’s luxurious Fifth Avenue Hotel. Although all were well dressed, there were two distinct groups. One group was youthful and in prime physical condition; the other was more mature and perhaps not so physically robust. Both were, however, there for the same purpose, a purpose more revolutionary than the venue and their affluence suggested. Their goal was to replace the existing structure of major-league baseball with a new order, one much fairer to the players who were, after all, the ones the fans paid to see. Just as the meeting was about to get underway, however, those in charge realized one of the eight clubs was not properly “organized.” While the others waited more or less impatiently, the leaders of the Brooklyn entry in this new baseball league adjourned to Parlor F and elected Wendell Goodwin president, Edward Linton vice president, John Wallace secretary, and George Chauncey treasurer. With that done, the meeting began with the Brooklyn club ready to take part in what is known to history as the Players’ League.1

Considering everything that had happened over the previous six months, it was understandable the new Brooklyn baseball owners were still completing the details of their new club. After all, it had been only on July 14 that the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players, also meeting at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, voted to form a new league to compete against the baseball establishment that had treated them so shabbily for so long.2 While the players had the talent to provide the best baseball possible, they lacked the financial wherewithal to build new ballparks and pay for everything else necessary to create a new league. The most likely source of those funds, beginning with $20,000 ($400,000 today) per club, was investors who, no matter how much they supported the players’ cause, were businessmen who “expected to earn a profit.”3

Further complicating the local situation was a sea change in the baseball landscape in Brooklyn, then an independent city. On November 11, Charles Byrne announced that his 1889 American Association championship club was leaving that circuit to join the National League.4 As a result, the stage was set for three teams to compete for the attention and money of Brooklyn baseball fans – the Dodgers5 plus new teams in both the American Association and the Players’ League. If there were any doubts that Charles Byrne intended to vigorously defend his market position, they were dispelled when Byrne quickly showed his “energy and grit” by signing what the Brooklyn Daily Eagle called the “cream of its champion team.”6

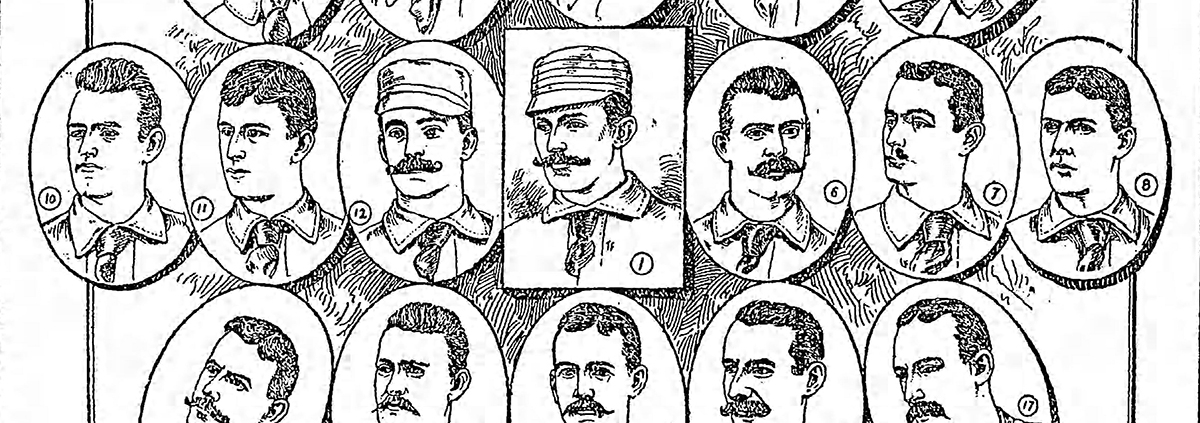

Apparently not intimidated, the Brooklyn Players’ League officers bought all of the required $20,000 of capital stock (10 percent down), leaving out others who supposedly wanted to invest. Prudently limiting their risk, the incorporators sold off some of their stock and some 25 shareholders wound up owning stock in the new club.8 In keeping with the new league’s philosophy, John Montgomery Ward, who would also captain the team and play shortstop, was included with the officers as a part-owner Ward, however, would have to concentrate on the on-the-field product, not to mention his role as union president. As a result, the remaining ownership responsibilities were left to the so-called “money men,” primarily Wendell Goodwin, George Chauncey and Edwin Linton.10 Like most other Players’ League owners, the Brooklyn officers were wealthy, well known in their communities and with business interests “which would directly benefit from the presence of a major league baseball team.” Other investors in the Brooklyn Players’ League team included Austin Corbin, Henry F. Robinson and George Wirth, who would become the club’s secretary. Besides Ward, one other player, Ed Andrews, purchased stock in the team.11

Ownership’s most pressing challenge was one of every baseball owner’s primary responsibilities, providing an attractive and accessible venue. Goodwin, Linton, and Chauncey’s approach to this issue speaks volumes about their motivation for investing in baseball and the probable outcome. Leading the way, although nominally only second in command, was Edward F. Linton, described as a “bundle of energy packed into a small frame” who “offended people daily,” “but was admired in spite of that, because he was so effective.”12 Born in Baltimore in 1843, Linton grew up in Massachusetts, served in the Union Army in the Civil War, and by 1877 was the owner of the immodestly named Unexcelled Fire-works Company of New York City. In 1880 he was severely burned in a fire at the company’s factory in the New Lots section of Brooklyn; that incident led to a career change with implications for the site of the Players’ League park. New Lots was originally settled in the eighteenth century by Dutch farmers. Beginning about 1855, their descendants began selling off the farmland to developers. Linton bought a farm near the last trolley stop and turned the tract into 600 housing lots. By 1890 Linton “literally owned” half of what in 1886 had become East New York, Brooklyn’s 26th Ward.13 If it wasn’t already obvious where Linton wanted the team to play its home games, Joseph Donnelly, writing in Sporting Life, removed any doubt, claiming that Linton’s “one idea is to develop the new section of the city, where his property interests lie.”14

Ownership’s most pressing challenge was one of every baseball owner’s primary responsibilities, providing an attractive and accessible venue. Goodwin, Linton, and Chauncey’s approach to this issue speaks volumes about their motivation for investing in baseball and the probable outcome. Leading the way, although nominally only second in command, was Edward F. Linton, described as a “bundle of energy packed into a small frame” who “offended people daily,” “but was admired in spite of that, because he was so effective.”12 Born in Baltimore in 1843, Linton grew up in Massachusetts, served in the Union Army in the Civil War, and by 1877 was the owner of the immodestly named Unexcelled Fire-works Company of New York City. In 1880 he was severely burned in a fire at the company’s factory in the New Lots section of Brooklyn; that incident led to a career change with implications for the site of the Players’ League park. New Lots was originally settled in the eighteenth century by Dutch farmers. Beginning about 1855, their descendants began selling off the farmland to developers. Linton bought a farm near the last trolley stop and turned the tract into 600 housing lots. By 1890 Linton “literally owned” half of what in 1886 had become East New York, Brooklyn’s 26th Ward.13 If it wasn’t already obvious where Linton wanted the team to play its home games, Joseph Donnelly, writing in Sporting Life, removed any doubt, claiming that Linton’s “one idea is to develop the new section of the city, where his property interests lie.”14

The problem with East New York as a home for the new team was its distance from Brooklyn’s population center. Access therefore depended upon mass transit, which explained Wendell Goodwin’s interest in the new venture. Born in New Hampshire, Goodwin was a Harvard graduate who had held executive positions in ship brokerage and telegraph companies before joining the Kings County Elevated Railroad as vice president.15 Founded in 1878, the steam railroad had multiple problems before finally opening its first five miles of track in April of 1888.16 About 18 months later, on November 18, 1889, just as the Players’ League was being born, service reached East New York.17 The need to increase passenger traffic drove Goodwin’s priorities for where the new team would play. Contemporary descriptions of Goodwin suggest a charismatic, friendly person, a far better public face for the organization than the intense Linton.18

Unlike his two partners, George Chauncey at least had some baseball experience as a player with Brooklyn’s old Excelsior Club. Like Goodwin, Chauncey was very personable and “a never-failing booster of Brooklyn.”19 Chauncey also had something in common with Linton – the real estate profession, although in Chauncey’s case, it dated back to prior generations through the family owned D&M Real Estate firm, founded in 1843.20 While Chauncey’s interests were much broader than Linton’s focus on the 26th Ward, his primary motivation was real estate, not baseball. Joseph Donnelly, who didn’t seem enamored with the new club’s ownership group, conceded that Chauncey was “a good fellow” but worried that he “has so much on his hands with his real estate business.”21

The Brooklyn Players’ League club had an ownership group of clearly competent men, but their more than a little mixed motivation made their priorities a real concern. While he obviously had his own agenda, it’s no wonder Dodgers owner Charles Byrne sarcastically labeled his new competition “a purely philanthropic enterprise.”22

The Brooklyn Players’ League club had an ownership group of clearly competent men, but their more than a little mixed motivation made their priorities a real concern. While he obviously had his own agenda, it’s no wonder Dodgers owner Charles Byrne sarcastically labeled his new competition “a purely philanthropic enterprise.”22

Ready or not, however, Goodwin, Linton, and Chauncey, along with Ward were baseball owners with all of the related responsibilities. With only about four months until Opening Day, they needed to build a ballpark, put together a roster and participate in league governance, including schedule making. At the time, finding the right site for a new ballpark was probably more difficult than actually building it because the sole advantage of the era’s wooden ballparks was the relatively short construction period. In this case, however, choosing a location wasn’t complicated because of Goodwin and Linton’s shared agenda. It’s no surprise, therefore, that the site was announced in mid-November before the ownership group was even made public.

According to the Eagle, the Ridgewood Land and Improvement Company purchased land in East New York for $88,000 which was to be leased to the Brooklyn Players’ League Club. Charles Byrne may have inadvertently brought the property to the attention of his soon-to-be rivals by previously considering the site as a home for his team. The Dodgers owner reportedly abandoned the idea because of the risk that the City of Brooklyn might put two streets through the site, a concern clearly not shared by the new owners. George Chauncey further benefited from the transaction by acting as the real estate agent on the purchase.23 Having chosen the location for their own interests, not those of their prospective fans, the new owners had an answer for any concerns about accessibility. Articles in the Brooklyn Citizen and the Eagle claimed the new park, bounded by Eastern Parkway, Vesta Street, Sutter Avenue, and Powell Street, was quite convenient by mass transit especially by – to no one’s surprise – the Kings County Elevated Railroad.24 Even with mass transit, however, the reality was that the park was “on the outer fringes of Brooklyn,” a statement equally true today.25

Having chosen the location for their new ballpark, Brooklyn Players’ League owners seemed in no particular hurry to build it. By mid-February, the architectural plans were not complete.26 At least one decision had apparently been made, however: The field would be called Atlantic Park in honor of the great Brooklyn team of baseball’s pioneer period.27 By early March, the site, according to Joseph Donnelly, was still little more than “a plain of meadow land, stretching off to the east with here and there a house to break the monotony.”28 Finally, on March 11 the Brooklyn Daily Times reported that a building permit had been issued and reports of construction that would supposedly cost $45,000 ($900,000 today) began appearing in the newspapers.29 Such reports, however, quickly got ahead of reality. Donnelly, after reading stories that the bleachers were up and the grandstand almost complete, made a personal visit only to find that “a spade had not been put in the ground.”30 Brooklyn’s experience was not unique as the Eagle reported that only three of the new Players’ League parks were “advancing towards completion” while Brooklyn and three others had “yet to be begun.”31

An exhibition game was scheduled for early April, but only a few seats were ready and the field itself was so much “slush,” that the Eagle said the game would “have to be played in mud” that was “ankle deep.”32 In spite of this dire prediction, not only was the game played, some 2,500 fans attended in what was standing room only, but not for the usual reasons. In what was intended as a positive note, the Eagle reporter mentioned that the park was less than 35 minutes from the Brooklyn Bridge with no need to change trains, so the new team should “obtain an equal share of the baseball patronage.”33 Amid the construction delays came news that the new grounds would not be called Atlantic Park after all, because too many saloonkeepers had co-opted the name. Instead, the new field would be called Eastern Park.34 Only two days before the April 25 opener, the grandstand was still not finished, but at least the chairs had been installed a day earlier in a facility now reported to have cost $150,000 ($3 million today).35 Rain washed out the home opener, but on April 28 Eastern Park opened with a 3-1 Brooklyn victory over Philadelphia.36 While it hadn’t happened in a timely manner, the Brooklyn owners had met their responsibility of providing a venue, albeit one whose accessibility was questionable. Attendance, however, would also depend on the schedule and the quality of the team.

While the Players’ League ballparks were not built quickly, signing players to play in them was another matter. On December 17, 1889, the New York Sun reported that almost 100 players had signed with the new league, at least 10 per team with Brooklyn inking 11.37 Since the players’ main grievances were against the National League, those clubs’ rosters were the new league’s primary target. In the end, former National League players outnumbered American Association alumni 3 to 1, but interestingly, on the Brooklyn club it was more like 50-50.38 Nor did Ward limit himself to major leaguers, signing minor leaguer Bill Joyce on the recommendation of Charles Comiskey. Joyce played third base for Brooklyn in 1890 and went on to have a solid major-league career.39 All told, Ward put together a strong lineup for the team that would be known as Ward’s Wonders. Ward’s very presence in Brooklyn was no small accomplishment. Legal action was necessary to release him from any obligation to the New York Giants even when he was supposedly headed to the Players’ League New York counterpart before being shifted to Brooklyn, perhaps to help attract investors.40

Among those signed by Brooklyn were pitchers Gus Weyhing, a 30-game winner with a 2.95 ERA, Lou Bierbauer, a .300-hitting second baseman, and first baseman Dave Orr, a .300 hitter in Brooklyn in 1888 who would perform even better in his return engagement. Perhaps the most creative signing was that of George Van Haltren, who pitched for Chicago in 1887 and 1888 before hitting .322 as an outfielder in 1889. The versatile player would fill both roles for the Brooklyn team in 1890. Although players would not receive their new, and presumably higher, salaries until spring, by February Sporting Life estimated that Brooklyn had paid $4,000 to $5,000 in advances. The source was the owners’ payment of the balance due on the initial capitalization of $20,000, all of which had reportedly been paid.41 Ward and the team could not hold on to Jerry Denny and Jack Glasscock, two solid players who decided to remain in the National League.42

Of all the decisions the new league had to make, none was arguably more important than the schedule. The Players’ League had already made a fateful decision in that regard by placing seven of its eight teams in direct competition with National League clubs, destroying not only the established leagues’ territorial monopoly, but also denying themselves a similar advantage.43 It’s difficult today to appreciate the importance of the schedule at a time when ticket sales were by far the primary source of revenue. This was magnified even further in Brooklyn and the rest of the Sabbath-observing East where baseball was prohibited on Sunday, the one day most people were off from work. Competition for holiday games and other prime dates was so fierce that debate on the 1888 National League schedule lasted 12 hours, until 3:00 A.M.44

While the process in the two established leagues had been substantially improved thanks to the Dodgers’ Charles Byrne and Charles Ebbets, the addition of a new league added the further complication of head-to-head competition.45 Initially the National League was hampered by its 10-club makeup and its original schedule averaged 40 head-to-head conflicts with Players’ League teams.46 When, however, the senior league bought out two franchises, it revamped its schedule to follow the same strategy it used to defeat the Union Association in 1884 – as much direct competition as possible.47 The result was 58 direct conflicts in Brooklyn with only Boston (60) and New York (63) having more.48 As John Ward told the Eagle, the National League “seems to have declared war to the knife.”49 The new Brooklyn team in the American Association wanted no part of head-to-head matchups with either league and had only 25 conflicts out of 70 scheduled home games.50

In response the new league called a special meeting to consider whether to change its schedule, but decided not to (Brooklyn concurring). The players preferred direct competition and both owners and players appreciated that any changes would simply be met by similar National League adjustments.51 It was a significant decision, especially given the nature of contemporary schedules. Because traveling was so time-consuming, teams alternated long homestands with equally long road trips. Had the two leagues chosen the continuous baseball approach used today, each league would have had a captive market when the other team was away. Instead there would be long periods of head-to-head competition, followed by gaps without any major-league baseball. It was a decision Linton, Chauncey, and Goodwin would have reason to regret.

By mid-April the schedule was in place, ready to serve as a measuring stick for the owners’ decisions about the ballpark and the roster. Considering how the workers scrambled to finish Eastern Park, it was a good thing Brooklyn opened the season with a five-game series in Boston. After losing three of the five, Ward’s team opened Eastern Park on April 28, defeating Philadelphia 3-1 before a crowd of between 2,500 (The Sun) and 4,750 (Brooklyn Citizen).52 Although the Wonders were only 4-4 on April 30, they got going in May, compiling a 17-9 record that left them only one game behind first-place Boston. June, however, was not as kind to Brooklyn and a 10-15 record dropped them five games off the pace.

Ward’s team got hot in July, and the Wonders stayed in the thick of the race through August while never quite catching front-running Boston. Brooklyn fans who hoped for an exciting stretch drive were doomed to disappointment, however. Only 1½ games back on August 31, the Wonders fell off the pace during the first 10 days of September, finally finishing 6½ games behind Boston. While Brooklyn didn’t win the Players’ League flag, the team gave its fans plenty of winning baseball, going 46-19 at home.

No matter how many games the team won, however, its long-term viability depended on how many people paid to watch. After some encouraging numbers for the first six games, attendance quickly dropped. According to figures published in the Eagle, Sun, and Citizen, only four of the next 19 home games attracted crowds of 1,000 or more. After the June 9 game, the team stopped releasing attendance figures, but the Sun vowed to publish its own estimates.53 At least some of the Players’ League magnates were having second thoughts about going head to head with the National League. At an owners meeting on May 30-31, prompted by the Pittsburgh club, the subject was reconsidered, but there was a 6-to-2 vote against making a change. While the individual votes were not released, it appears Brooklyn was with the majority.54

If the schedule wasn’t going to change, the next alternative to attract fans was to cut ticket prices, but both the Dodgers’ and Wonders’ owners denied reports that this would happen.55 No longer on the scene was the new Brooklyn American Association team, which disbanded on August 25.56 Both the contemporary media and historians agree that the official attendance figures were, in historian Charles Alexander’s words, “shamelessly exaggerated.”57 While the Brooklyn Players’ League figures will never be known, a compilation of media estimates and team-announced figures put Eastern Park attendance at about 80,000, some 40,000 less than that of the pennant-winning Dodgers. It was, however, a pyrrhic victory for Charles Byrne, whose club had drawn over 353,000 fans just a year earlier.58

Just before the home opener, a reporter had asked Ward if 1,500 paying customers per game would cover expenses. While the Brooklyn captain claimed not to have done the math, he said the club had total expenses of $75,000 ($1.5 million today). On that basis, the reporter calculated the club would lose $10,000 ($200,000), so obviously average attendance of just over 1,200, if accurate, meant even worse financial results.59 Any doubts about the seriousness of the club’s financial situation were eliminated by reports of liens of about $16,000 ($320,000 today) filed against the Ridgewood Land Company for unpaid construction bills.60 Clearly some of the debts were due to the failure of the club to pay the $7,500 ($150,000) rent.61

Had this sea of red ink been limited to Brooklyn, the overall Players’ League might have been salvageable, but unfortunately for the players and their cause, league secretary Frank Brunell estimated that only one of the eight clubs (Boston) made money. Total losses were estimated at $125,000 ($2.5 million). Brooklyn supposedly lost $19,000 ($380,000). The highest losses, $20,000 ($400,000), were posted by Buffalo, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia. Nor were the deficits limited to the new league. Brunell put total National League losses at an even greater $231,000 ($4,620,000), including a $25,000 ($500,000) deficit at Brooklyn’s Washington Park.62 No owner could have been satisfied with the situation, but the most shocked were likely the financial backers of the Players’ League who, according to James Hardy, had made the “incredible assumption that professional baseball was el dorado” when “it was just the opposite.”63 The reality was that late nineteenth century baseball was a highly competitive business, in which it was hard to make money. This was even more true for owners like the Brooklyn group, who made baseball decisions based largely on their nonbaseball interests.

Since few, if any, of the owners in the new league had unlimited wealth, it’s no surprise that the Players’ League owners were readily available when National League owners offered to discuss the situation at a “peace meeting” on October 9, 1890.64 While there may have been multiple options, the Dodgers’ Charles Byrne had already launched a preemptive strike, claiming in the Sun that the only solution was one team per city.65 Although the players, especially John Ward, wanted a place at the table, it soon became clear that National League owners could and would prevent this. With that resolved, the only question was how to restore peace to the baseball world. Charles Byrne argued that the best approach was direct negotiations between competing clubs instead of leaguewide discussions.66 That, as Byrne doubtless intended, put the future of major-league baseball in Brooklyn in the hands of those with the most to gain or lose.

Writing many years later, historian Harold Seymour claimed that Wendell Goodwin’s presence at the October 9 meeting signaled that he was “primarily interested in salvaging” things for himself and his associates.67 Much closer to the event, Frank Brunell, doubtless with more than a little bitterness, said the Brooklyn and New York owners caved in for “selfish reasons.”68 And, to remove any doubt, Goodwin in early December acknowledged that it was his “business to look out for that road [Kings County Elevated Railroad]” and he would “look out for [it] in making a settlement.”69 It wasn’t as if there were a lot of options, as Dodgers co-owner Ferdinand Abell told the New York Clipper. One party could buy the other one out or they could consolidate into one club.70 The possibility of the Players’ League group buying out Byrne, Abell, and company was more than a little alarming to Joseph Donnelly, who feared that the dominance of real estate and railroad interests made it unlikely that major-league baseball in Brooklyn would “prosper” under their leadership.71 The scribe needn’t have worried: The combination of losses already incurred and a purchase price of $125,000 ($2.5 million today) basically eliminated that possibility.72

Byrne and his partners, doubtless sensing the Players’ League’s weak negotiating position, likely saw no benefit in buying out their rivals. Instead they proposed a consolidation where the Players’ League group would get a minority position in a Dodgers team that would continue to play at Washington Park.73 Considering, as the Eagle reminded its readers, that Goodwin and company got involved only to further their interests in the 26th Ward, playing at Washington Park quickly became “the only difficulty” preventing a settlement.74 A Dodgers move to East New York, however, found few supporters, with the Sun warning that if the club made the move, “about all it will draw will be the cold sea breeze in the spring and fall.”75 Adding to the chorus of those opposed to the possibility were fans, sending “letters by the score daily” urging the club to remain at Washington Park.76 To this day, why Byrne and his partners even considered the possibility is hard to understand, especially since the Players’ League group in debt and without a league had an extremely weak negotiating position. In spite of the strength of the Dodgers’ position, however, the Eagle claimed that if the Players’ League owners paid the “full cost of the change” to Eastern Park, the consolidation could take place.77 After proposing $50,000 ($1 million) as the “full cost,” Byrne compromised on $40,000 ($800,000) with $30,000 in 30 days and an additional $10,000 in the spring. The transaction took the form of a new corporation with $250,000 in capital stock. The Dodgers owners held $126,000 and the Players’ League group owned a minority position of $124,000.79 As Byrne explained it to the Eagle, the new corporation then made a separate agreement with Goodwin and his partners to move the team to Eastern Park for $40,000.80

The proposed terms were agreed on by early January of 1891, but anyone who thought the deal was done hadn’t reckoned with “the grumbler among the East New Yorkers,” one Edward Linton.81 After Goodwin presented the proposal at a shareholders meeting on January 5, Linton was reportedly on his feet, calling the arrangement “outrageous and foolish,” one that would not benefit from his money. Unlike almost everyone else in baseball, the disgruntled director claimed the Players’ League was not dead and would likely form a new league with the American Association.82 Arguments to the contrary probably carried little weight with Linton, who earlier argued that a “league” of just four teams, two each in Brooklyn and New York, “would have the greatest season” in baseball history.83 Linton even said that rather than accept the proposed consolidation, he was willing to assume all of the risks and use his own money to move forward.84 There was, however, more than a little fine print in Linton’s proposal. It depended upon “a nominal rent” for Eastern Park and “a moderate subsidy” from the Kings County Elevated Railroad.85 Linton, however, was not all talk; he stopped the proposed deal by getting a temporary injunction.86 It was also suggested that George Chauncey, who was not named in the injunction, also opposed the deal.87

Goodwin and Byrne, however, were not impressed with Linton’s antics. According to Goodwin, the majority of the board believed Linton just wanted to be bought out while Byrne asserted that it was “hard to treat seriously anything [Linton] says or does in the matter.” Byrne added that he had previously met with Linton, who demanded to be bought out for $3,500 ($70,000) or he would make trouble.88 Obviously, the best solution was to be rid of Linton and that’s what happened when he was paid about $8,300 ($166,000 today) for his stock, advances, and stock held by his friends. If the claim was correct – that Linton received full value for a friend’s stock that Linton had purchased at half-price – the value of his friendship was more than a little questionable.89 Some even speculated that Linton waited until Goodwin got a deal that benefited Linton’s real estate interests before forcing the buyout.90 While there were rumors that Chauncey would also try to force a buyout, in the end he, as well as Goodwin and some of the others, became Dodgers stockholders until Charles Ebbets bought them out in late 1897.91 Finally on February 7, 1891, the Players’ League Club board approved the agreement, ending the Brooklyn chapter of the 1890 baseball war. Obviously, it had not been a good year for major-league baseball in Brooklyn and the prospects for the future were far from certain. Most of the city’s baseball fans, however, probably cared more about an Eagle headline that read: “Get Ready for Baseball.”92

JOHN G. ZINN is the chairman of the board of the New Jersey Historical Society. He is a two-time winner of SABR’s Ron Gabriel Award in 2019 for his book “Charles Ebbets: The Man Behind the Dodgers and Brooklyn’s Beloved Ballpark” and in 2014 for “Ebbets Field: Essays and Memories of Brooklyn’s Historic Ballpark, 1913-1960,” co-authored with Paul Zinn. He was also honored in 2020 with the SABR Russell Gabay Award, which honors entities or persons who have demonstrated an ongoing commitment to baseball in New Jersey.

Notes

1 “The Fifth Avenue Hotel,” boweryboyshistory.com/2012/1/fifth-avenue-hotel-opulence-atop.html; Evening World, Third Edition, December 16, 1889: 1.

2 Charles Alexander, Turbulent Seasons: Baseball in 1890-1891, (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 2011), 14.

3 Robert B. Ross, The Great Baseball Revolt: The Rise and Fall of the 1890 Players League, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 89-90. Alexander, 25, assumes a 20-to-1 relationship.

4 Alexander, 16.

5 This team name is used because it is the enduring nickname of the franchise. There were a number of team nicknames over the years, all assigned by newspapers until the Brooklyn National League Baseball Club formally adopted Dodgers in 1932.

6 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 10, 1889: 1.

7 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 6, 1889: 6; December 11, 1889: 1.

8 Sporting Life, January 10, 1891: 3.

9 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 11, 1889: 1.

10 Alexander, 28-29.

11 Ross, 90, 106-107.

12 brownstoner.com/history/walkabout-the-landord-of-east-new-york-part-4/.

13 brownstoner.com/history/walkabout-the-landlord-of-east-new-york-part-1/.

14 Sporting Life, December 18, 1889: 2.

15 Boston Journal, second edition, March 3, 1898: 10; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 5, 1898, 5.

16 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 21, 1888: 6; April 24, 1888: 6.

17 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 19, 1889: 1.

18 Standard Union, March 4, 1898: 1; New York Times, March 6, 1898: 15.

19 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 16, 1926: 1.

20 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 11, 1891: 11.

21 Sporting Life, December 18, 1889: 2.

22 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 12, 1889: 6.

23 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 19, 1889: 1; Brooklyn Citizen, February 14, 1891: 3. The extent of joint ownership in the team and the real estate company isn’t clear, but Chauncey was its president. Other investors in what was described as a syndicate were Edward McAlpin and Edward Talcott, who were also owners of the New York entry in the Players’ League.

24 Brooklyn Citizen, November 19, 1889: 6, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 11, 1889: 1.

25 Ross, 129.

26 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 16, 1890: 11.

27 Sporting Life, February 19, 1890: 5.

28 Sporting Life, March 5, 1890: 2.

29 Brooklyn Daily Times, March 11, 1890: 1, Brooklyn Citizen, March 11, 1890: 1

30 Sporting Life, March 19, 1890: 4.

31 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 13, 1890: 1.

32 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 10, 1890: 2.

33 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 11, 1890: 1.

34 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 12, 1890: 1.

35 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 23, 1890: 2.

36 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 27, 1890: 20.

37 The Sun, December 17, 1889: 4.

38 Alexander, 35, 46.

39 sabr.org/bioproj/person/26fc29e0.

40 Ross, xiii-xvi, 108.

41 Sporting Life, February 12, 1890: 5.

42 Ross, 118-119.

43 Ross, 160.

44 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 4, 1888: 16.

45 John G. Zinn, Charles Ebbets: The Man Behind the Dodgers and Brooklyn’s Beloved Ballpark, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 2019), 21-22.

46 Sporting Life, March 12, 1890: 1; March 19, 1890: 1.

47 Zinn, 25.

48 Alexander, 48.

49 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 23, 1890: 2.

50 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 14, 1890: 6; March 17, 1890, 1.

51 Sporting Life, April 5, 1890: 8.

52 The Sun, April 29, 1890: 4; Brooklyn Citizen, April 29, 1890: 3.

53 The Sun, June 10, 1890: 4.

54 The Sun, June 1, 1890: 5.

55 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 21, 1890: 2; August 7, 1890: 2.

56 David Nemec, The Beer and Whiskey League: The Illustrated History of the American Association – Baseball’s Renegade Major League (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2004), 188-89, 197.

57 Alexander, 60; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 8, 1890: 1.

58 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 16, 1890: 2; John Thorn, Pete Palmer, Michael Gershman, and David Pietrusza, eds., Total Baseball: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball, Sixth Edition (New York: Total Sports, 1999), 105.

59 The Sun, April 27, 1890: 5.

60 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 8, 1890: 1; The Sun, September 10, 1890: 4.

61 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 12, 1891: 6.

62 Ross, 184; Sporting Life, November 22, 1890: 6.

63 James D. Hardy, The New York Giants Baseball Club: The Growth of a Team and a Sport, 1870-1900 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1996), 133.

64 Ross, 183.

65 The Sun, October 8, 1890: 4.

66 Ross, 188, 190-192.

67 Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 240.

68 Hardy, 130.

69 The Sun, December 4, 1890: 4.

70 New York Clipper, October 25, 1890: 521.

71 Sporting Life, November 15, 1890: 5.

72 The Sun, January 8, 1891: 6.

73 The Sun, January 8, 1891: 6; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 13, 1890: 6.

74 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 7, 1890: 8.

75 The Sun, December 9, 1890: 4.

76 Sporting Life, January 3, 1891: 7.

77 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 7, 1890: 8.

78 The Sun, January 8, 1891: 8; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 7, 1891: 6. In the end, Byrne and his partners received only $22,000 of the $40,000, making the deal look even worse in retrospect. Zinn, 31.

79 The Sun, January 8, 1891, 6.

80 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 8, 1891, 6.

81 Sporting Life, January 10, 1891: 9.

82 The Sun, January 6, 1891: 4.

83 The Sun, December 3, 1890: 4.

84 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 7, 1891: 6.

85 New York Herald, January 8, 1891: 8.

86 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 7, 1891: 6.

87 The Sun, January 7, 1891: 4.

88 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 8, 1891: 6.

89 The Sun, January 28, 1891: 4.

90 The Sun, January 24, 1891: 4; January 28, 1891: 4.

91 Zinn, 34.

92 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 8, 1891: 8.