Harriet and James J. Coogan

This article was written by Bill Lamb

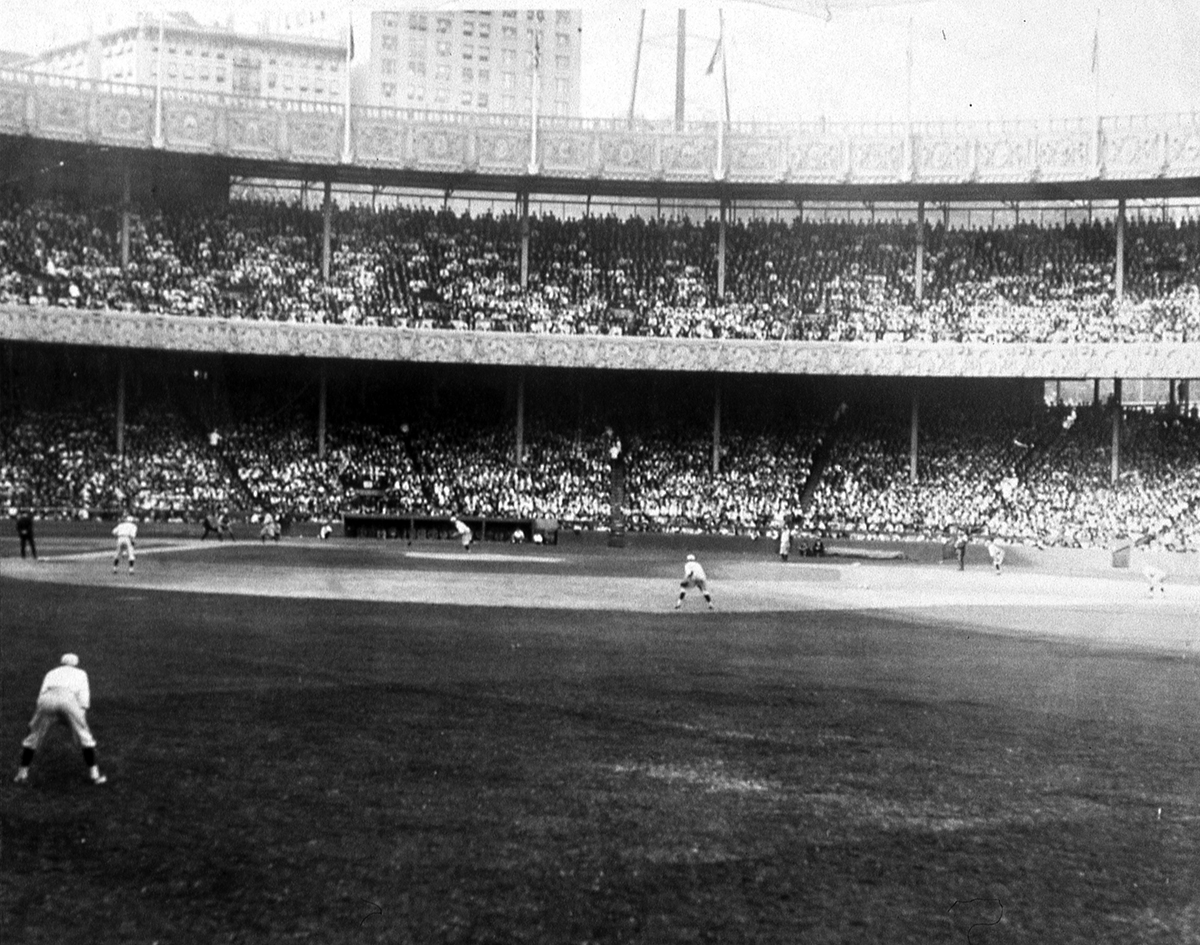

From early July 1889 until the removal of the franchise to the West Coast following the 1957 season, the New York Giants played baseball – often exciting and sometimes championship-caliber – at the northern Manhattan ballpark known as the Polo Grounds. Inexorably over the decades, Giants players, managers, club owners, front office personnel, sportswriters, and team rooters came and went. Even the Polo Grounds itself changed identity several times.

Through the years, however, one thing remained constant: the Giants’ dependence upon the family from whom it leased the real property on which its ballparks sat – the Coogans, or more particularly, the Gardiner-Lynch-Coogan family.

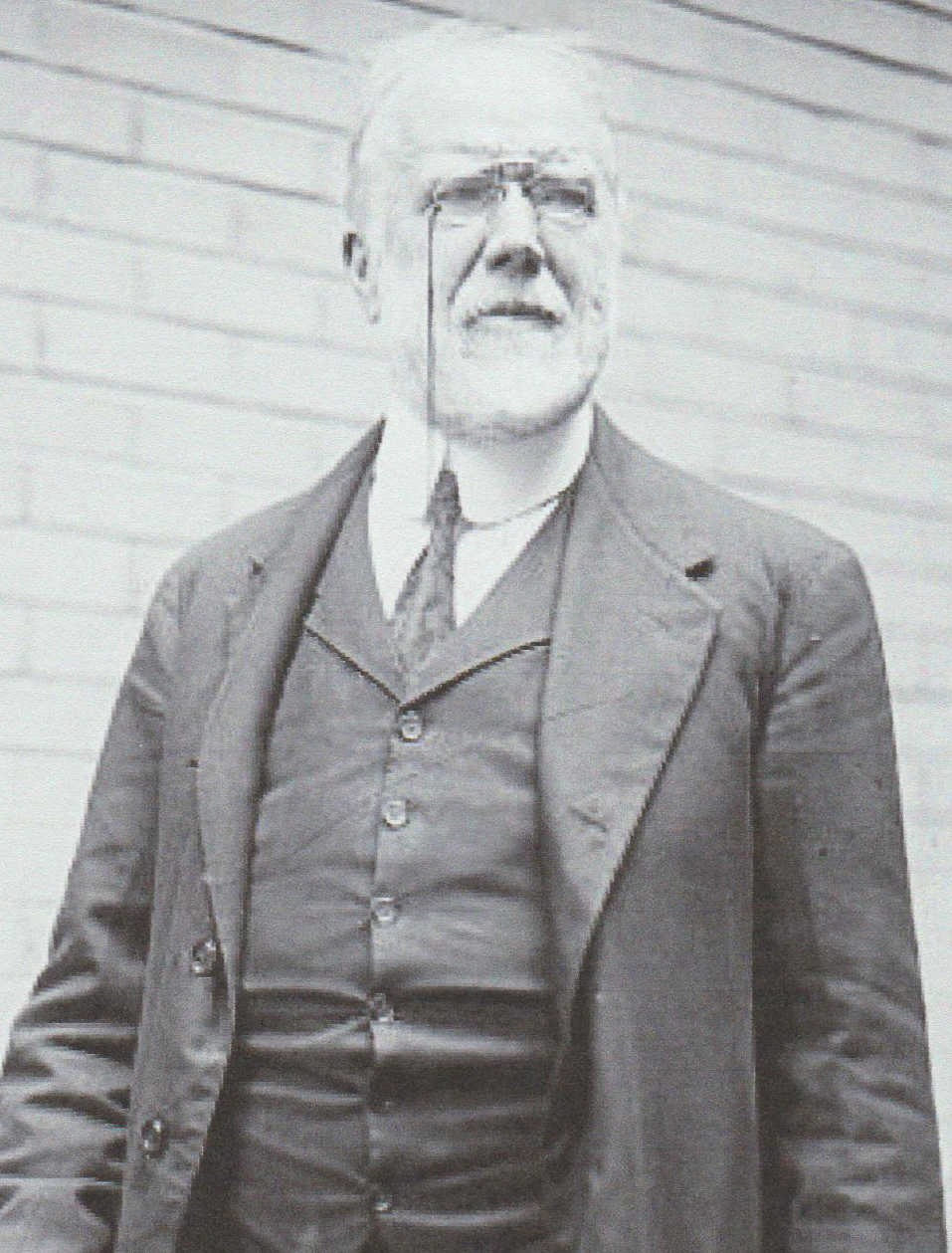

This article profiles the clan’s two most prominent members: James J. Coogan, the furniture dealer-turned-Manhattan politico who managed the family’s vast real estate holdings, and his heiress wife, the former Harriet Gardiner Lynch, a business-savvy but private woman who, after her husband’s death in 1915, assumed oversight of the family property portfolio and dealt with the Giants for the ensuing 30 years.

The Coogans were something of an odd couple, separated by considerable differences in age, affluence, and societal station. Throughout his life, James Jay Coogan was evasive about the year and place of his birth. But in all probability, he was born on January 16, 1845, in County Carlow, Ireland. James was the oldest of the six children1 known to have been born to Patrick Peter Coogan (1821-1905) and his wife Alice (née McGinty, 1825-1898).

About 1852, the Irish Catholic Coogans emigrated to America, settling in New York City.2 Once on their feet, Patrick Coogan and his brother James established a furniture-making business in lower Manhattan. Although he would obtain a law degree from New York University, our male subject was intended for the family business and trained in upholstery. Over time, he and younger brothers Edward and Thomas assumed control of the operation, soon headquartered in the Bowery and styled Coogan Brothers Furniture.

Catering to the Irish and German immigrants who had moved into the area and willing to do business via installment payments from its generally cash-strapped clientele, the business thrived, eventually opening outlets elsewhere in Manhattan.3 By the early 1880s, the Coogan brothers were prosperous city businessmen. But in the end, James J. Coogan made his fortune in a more time-tested way: he married money.

Catering to the Irish and German immigrants who had moved into the area and willing to do business via installment payments from its generally cash-strapped clientele, the business thrived, eventually opening outlets elsewhere in Manhattan.3 By the early 1880s, the Coogan brothers were prosperous city businessmen. But in the end, James J. Coogan made his fortune in a more time-tested way: he married money.

The circumstances under which Coogan met his future bride are lost to history. But on the face of it, the two appeared peculiarly matched. Unlike recent arrival Coogan, Harriet Gardiner Lynch was a member of one of America’s oldest and most distinguished families, a direct descendant of Lion Gardiner, the English merchant-adventurer granted privileges and property in the colonies by King Charles I in the 1630s. By the time of Harriet’s birth more than two centuries later, the Gardiner family had grown large and wealthy, with extensive property holdings in New York, southern New England, and elsewhere.4 But of interest, Harriet’s father was a man not unlike James Coogan. Like him, William L. Lynch was an Irish Catholic who had come to America as a youth and prospered in New York City, first as a grocer, thereafter as a tea merchant and importer. How this immigrant of humble origin became acquainted with WASP gentry like the Gardiners is another unknown. By the mid-1840s, however, Lynch had married teenage Sarah Gardiner and started the family that would eventually include eight children, all of whom were raised in their father’s Catholic faith.

Harriet was the youngest of the brood, born in Manhattan around 1861. Like her older sisters, she was dispatched to Long Island to be educated, finishing her schooling at the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Manhasset. By the time Harriet returned home, her father had become a wealthy man in his own right,5 having acquired title to some of the city’s choicest real estate (including property in far-north Manhattan that would later become home to the Polo Grounds).

As noted, how Harriet became a sweetheart of James Coogan, a man some 16 years her senior, is unknown. Whatever the circumstances, their subsequent betrothal was approved by Harriet’s parents.6 The two were married in 1883 at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, with no less a Church personage than the Very Reverend Michael Corrigan, the Archbishop of New York, officiating the ceremony.7 In 1885, son Jay (James Jay, Jr.), the first of the couple’s five children, was born.8 More important for our purposes, the by-then widowed Sarah Gardiner Lynch had entrusted oversight of income-producing family properties to new son-in-law James Coogan. The job was no sinecure: the holdings were considerable, and customarily leased by the family, rarely sold off. This attachment to property soon brought Coogan into ever-increasing contact with government officials seeking access or title to Gardiner-Lynch real estate (via condemnation or other legal proceedings, if necessary) in order to accommodate ever-growing city expansion/improvement plans.9

As Coogan fenced with city bureaucrats, New York Giants founder/owner John B. Day was having his own property problems with officialdom. Since September 1880, Day had leased a meadowland located just north of Central Park in Manhattan from sportsman-socialite James Gordon Bennett, Jr., the owner-editor of the New York Herald. Sometime earlier, Bennett had allowed the Westchester Polo Club to enclose a portion of the property so that admission could be charged for its matches. Occasional weekend polo with its small flock of blue-blooded patrons was no cause for alarm by the residents of the tony neighborhood.

But soon the polo club was gone elsewhere, replaced by summer-long baseball and the noisy, often uncouth crowds that games brought to the area.10 This was an entirely different, and most unwelcome, development. In March 1888, friendly forces on the City Council finally succeeded in pushing through adoption of a new traffic design plan that remedied the neighborhood’s problem with the Polo Grounds – by running a city street through the outfield. Rearguard legal action by Day stalled demolition of the ballpark long enough for the Giants to finish the 1888 season with a World Series victory over the American Association St. Louis Browns. Nevertheless, the club boss fully realized that the Polo Grounds was doomed, and that he needed to relocate the Giants for the 1889 campaign.

Late that winter, Joseph Gordon, a junior partner in the Giants operation and a Manhattan real estate maven,11 brought a possible new ballpark site to Day’s attention. The property was far-north Manhattan acreage reclaimed via diversion of the Harlem River and owned by the Gardiner-Lynch family.12 Interest in the property soon brought Day into negotiation with James J. Coogan, the family’s estate agent.

By early 1889, it is entirely possible that the two men were already acquainted. Both Day and Coogan were successful downtown Manhattan businessmen, and on the periphery of New York City politics, as well. Although not particularly active, Day, a well-heeled cigar manufacturer originally from Connecticut, was a member of Tammany Hall, the corrupt political machine that controlled Democratic Party affairs in Manhattan. Day had joined Tammany a decade earlier, shortly after he had moved to the city to open a new manufacturing plant on the Lower East Side.

While Coogan was still a principal of Coogan Brothers Furniture, marriage into a wealthy family had afforded him the financial wherewithal to indulge a passion to hold elective office. Because of his frequent business contact with the working classes, Coogan fancied himself a man of the people, and, as such, sought the mayoral nomination of the fringe Socialist Labor Party in 1886. Despite offering to spend $200,000 of his own (meaning his mother-in-law’s) money self-financing his campaign, Coogan’s proposed candidacy was roundly rejected by party convention delegates.13 Two years later, he reentered the political fray with a little more success, garnering the mayoral candidate slot on the United Labor Party ticket. The expenditure of the promised $200,000 in family money did his campaign little good. Coogan was trounced, finishing a distant fourth behind young Tammany Democrat Hugh Grant.14

While Coogan was still a principal of Coogan Brothers Furniture, marriage into a wealthy family had afforded him the financial wherewithal to indulge a passion to hold elective office. Because of his frequent business contact with the working classes, Coogan fancied himself a man of the people, and, as such, sought the mayoral nomination of the fringe Socialist Labor Party in 1886. Despite offering to spend $200,000 of his own (meaning his mother-in-law’s) money self-financing his campaign, Coogan’s proposed candidacy was roundly rejected by party convention delegates.13 Two years later, he reentered the political fray with a little more success, garnering the mayoral candidate slot on the United Labor Party ticket. The expenditure of the promised $200,000 in family money did his campaign little good. Coogan was trounced, finishing a distant fourth behind young Tammany Democrat Hugh Grant.14

Although far removed from bustling midtown Manhattan, the proposed ballpark site that Day and Coogan dickered over was flat, dry, and already used for pickup baseball games tolerated by the property owners. On one side, the site was bounded by a towering escarpment (later dubbed Coogan’s Bluff); on the other, the Harlem River.15 More important, the property was immediately adjacent to a recently constructed north Manhattan railway stop. Given all this, Day thought the spot suitable for a new Giants home and sought a long-term lease for the grounds. But uncharacteristically, the family wanted to unload the property, and it was for sale only. Negotiations soon foundered, prompting Day to place a remarkable notice in the New York Times. It read: “I want to find a party to purchase from the present owners, who will not lease, the plot of ground bounded by 8th and 9th Aves., 155th to 157th Sts., which I will lease for five to ten years, at a rental of $6,000 per year. JOHN B. DAY, President New York Base Ball Club, 121 Maiden Lane.”16

To no great surprise, a property-purchasing angel did not materialize, leaving Day without a ball field as the 1889 season opened. In desperation, the Giants played their first two home games at decrepit Oakdale Park in Jersey City. Day then removed the club to the St. George Grounds on Staten Island, the erstwhile home of the AA New York Mets, by then defunct. But wet weather and the inconvenient locale of the ballpark decimated attendance at Giants games. Quickly, it became clear to Day that playing outside Manhattan was a losing proposition. By now, fortuitously, the Gardiner-Lynch family had relaxed its position on the rental of the north Manhattan site, and negotiations between Day and Coogan resumed. On June 22, 1889, the parties reached agreement on a two-year lease of the grounds.17 But in an economy that he would soon have cause to regret, Day leased only as much land as he needed for his new ballpark, declining the opportunity to rent the tract in its entirety.

Working at a furious pace, the small army of workmen that Day loosed on the property erected a usable, if still unfinished, ballpark in a breathless three weeks.18 Christened the New Polo Grounds, the Giants inaugurated their new home field on July 8, 1889, with a 7-5 win over the Pittsburgh Alleghenys. An estimated crowd of 10,000 paid their way through the turnstiles, while another 5,000 freeloaders watched game action from atop Coogan’s Bluff, the Eighth Avenue Viaduct, the Harlem Speedway, and other elevated vantage points. The win augured a New York surge in National League standings that saw the club nip the Boston Beaneaters at the wire for the pennant. The Giants then successfully defended their World Series crown with a postseason triumph over the AA Brooklyn Bridegrooms. Although he was not known to be a baseball enthusiast, James J. Coogan was impressed by the throngs paying their way into the new ballpark that summer. Consequently, even before the season was done, Coogan made Day a $200,000 offer for the purchase of the Giants.19 But in another decision that he would soon have reason to second-guess, Day turned Coogan down.

The arrival of the Players League and the havoc which it caused the baseball establishment during the 1890 season is beyond the scope of this essay. Suffice it to say that James J. Coogan contributed to the stress endured by the ownership of the NL New York Giants. Even though he already had a tenant on site, Coogan had no inhibition about leasing the remainder of the property to Players League investors headed by young Wall Street financier Edward B. Talcott.20 Within months, Brotherhood Park, home of the PL New York Giants, was sitting directly adjacent to the National League Giants ballpark, their dimensions separated only by a 10-foot-wide passageway and the stadium walls. While Brotherhood Park was going up, Coogan attempted to pressure Day into surrendering his lease to the New Polo Grounds but was quickly and emphatically rebuffed. Day’s ball club was not going anywhere.21 In fact, only two months after Coogan had tried to force the NL Giants out of its ballpark, Sporting Life reported that: “The New York League club has found a way to vault the obdurate landlord Coogan’s stony heart and has secured a five-year lease of the New Polo Grounds. The terms were not divulged, but it is safe betting that Coogan didn’t get the worst of the bargain by a very, very long shot.”22

In the aftermath of the financial bloodbath suffered by both their clubs and with the Players League headed for oblivion, NL Giants boss Day and PL Giants leader Talcott agreed to merge their franchises. The consolidated nine would play the 1891 season as a National League team. Brotherhood Park, renamed the Polo Grounds, would be used as the club’s home base, while the other ballpark at the site would become Manhattan Field and serve as a site for non-baseball events. But some weeks after the season’s close, Coogan was back on scene to complicate matters. In November 1891, he was approached by representatives of the American Association seeking to place a club in New York. To that end, they wanted to lease “the land adjoining the Polo Grounds for a new ballpark.” When asked about the AA overture, Coogan stated, “I told them that I would lease the land and that is all I am prepared to say.”23 The ensuing demise of the American Association, however, rendered the matter moot. And within a few seasons, control of the New York Giants passed to a club owner whom Coogan was loath to cross: Andrew Freedman.

Although his election efforts had thus far been fiascos, Coogan’s thirst for public office had not slaked. And it finally occurred to him that the easiest way to achieve his political ambitions was to work his way into the good graces of Richard Croker, the all-powerful and avaricious chief of Tammany Hall – a matter facilitated by Coogan’s access to the Gardiner-Lynch family fortune. Given that Freedman was a political protégé, business associate, and close friend of Croker, Coogan took pains not to antagonize the often prickly club owner. From here on, the Giants’ lease to the Polo Grounds/Manhattan Field property was renewed in a timely manner, with minimum fuss.24

Before Coogan could much advance his political prospects, they were threatened by calamity in his business affairs. While increasingly serving the interests of the Gardiner-Lynch family, Coogan remained a principal in Coogan Brothers Furniture. But a disastrous warehouse fire and a depressed economy (the Panic of 1893) had sent the business into a tailspin. When the brothers could not pay their bills, creditors filed suit.25 By January 1894, James’s finances were in such distress that he was obliged to seek bankruptcy protection. In a humiliating petition filed with the court, Coogan averred that he was penniless; that he was entirely dependent for support upon his mother-in-law (with whom he, his wife and children lived); and that he could not satisfy the numerous judgments lodged against him.26

The failure of Coogan Brothers Furniture subsequently produced an even unhappier event. Edward Coogan initiated a civil suit alleging that his brother James and mother-in-law Sarah Lynch27 had engaged in conspiracy, fraud, and other improprieties related to the winding-up of the furniture business.28 In time, the suit was settled out of court. During pre-settlement courthouse proceedings, however, it was revealed that Sarah Lynch had been quietly transferring her assets to daughter Harriet Coogan. By now, sad to relate, seven of Sarah’s eight children were deceased, leaving Harriet her sole surviving immediate heir. Dissipation of a person’s estate by distribution of assets prior to the testator’s death was an effective way to avoid inheritance taxes, and a standard practice of the rich. It was also perfectly legal. By the time the intra-family squabble was resolved, Harriet Coogan had assumed virtually all the wealth of the Gardiner-Lynch family.29 Given his presumed access to his wife’s money, this lent credence to an August 1899 report that Coogan had recently offered “his friend Andrew Freedman” $100,000 for the Giants franchise.30 If such an offer was, in fact, made, nothing ever came of it.

As Harriet came early into her inheritance, the political fortunes of James J. Coogan were also in ascendance. Having finally ingratiated himself with Boss Croker, Coogan was the Tammany-designated replacement Manhattan Borough president when incumbent Augustus W. Peters unexpectedly died in office in late December 1898.31 The post was largely a ceremonial one, with few official duties to be performed. Coogan got himself into trouble anyway, voting in Southampton, Long Island (not Manhattan) in the November 1900 local elections. This put Coogan’s place of residence (and thus his continued eligibility for the Manhattan borough president post) in question, and an official inquiry into the issue was briefly conducted.32 But as long as Tammany held power, Coogan, by then a major contributor to Democratic Party campaign coffers, was in little jeopardy.33 Rather, it took the reform tide of November 1901’s New York City municipal elections to sweep him and other Croker vassals from office. That election ended the political career of James J. Coogan; he more or less retired from working, as well. In the coming years, his much younger wife would handle most of the family’s business affairs, including its relationship with the New York Giants.

As the new century unfolded, Harriet Coogan, rather than her husband, was customarily recorded as the party of interest in family real estate transactions.34 This included the 1903 foreclosure sale purchase of Whitehall, a Newport, Rhode Island, mansion designed by the famed architect Stanford White.35 Newport had become the summer playground of the country’s Gilded Age millionaires, and ultimately became the site of an epic feud between Harriet Coogan and the resort’s society matrons.36 At first, the newly arrived Coogans seemed reasonably well-received. Harriet was a frequent presence at art shows, horserace meets, and other social gatherings, while her children (by then young adults) quickly became popular with Newport’s junior set.37 But Coogan-hosted galas proved second-tier social events, attended by only the lesser local gentry. Their invitations were routinely declined by the Vanderbilts, Belmonts, Whitneys, and other members of Newport’s aristocracy. The crème de la crème also avoided socializing with the Coogans at public events.

When the situation was autopsied decades later, the snobbish attitude toward the Coogans was attributed to the elite’s disdain of social climbers.38 But that assessment is strained, if not absurd. The Vanderbilt-Belmont crowd were parvenus, their fortunes of commercial origin and recently made.39 In sharp contrast, Harriet Coogan was a Gardiner, descended from a landed family that traced its wealth back to the reign of 17th century Stuart kings.40 More likely, it was her husband James who was found objectionable: Irish, low-born, and a Tammany Hall political hack. And although never mentioned in newsprint, there was also doubtless more than a whiff of society disdain of the Coogans’ Catholicism. Whatever its basis, upper crust Newport’s antipathy for the Coogans reached its apogee in 1910.

The event which brought matters to a head was a large dinner party hosted by the Coogans at Whitehall early that summer.41 Over 400 guests were anticipated, including the Newport aristocracy who, unexpectedly, had accepted invitations to attend. To ensure the evening’s success, Harriet pulled out all the stops: musicians, lavish catering, extra wait staff, Whitehall exquisitely decked out. Even 40 tuxedo-clad young men were recruited to fill up any empty chairs and to dance with the ladies. Then James and Harriet Coogan waited – until midnight – for the guests who never came. Reportedly acting at the direction of society grand dames bent on humiliation of the Coogans, not one of the 400 invitees showed up.42 James Coogan, his hide toughened by a life in trade and politics, brushed off the affront. But his wife was not having it.

Whatever satisfaction Newport society derived from the pointed insult, it would soon rue the day that it offended the proud and fierce Mrs. James J. Coogan. Within days, Harriet had collected her family, servants, and staff, and whisked them out of Whitehall, leaving the mansion’s furnishings, expensive family wardrobe, art collection, and other valuables behind. She did not even lock the mansion doors, allegedly telling an alarmed personal secretary that the place “can rot to its roots.”43 Predictably, the unprotected Coogan residence was quickly looted. Thereafter, it became a flophouse for vagabonds drawn to the comfort of free shelter among the Newport elite. At the same time, the untended mansion grounds defaced its posh surroundings. A March 1911 Whitehall fire likely started by a drunken squatter then further damaged the premises.44 All the while, Harriet ignored entreaties to have Whitehall repaired, leaving a decaying, rat-infested eyesore right in the middle of the Newport aristocracy’s ritziest neighborhood. And because Harriet ensured that Whitehall property taxes and other municipal assessments were always promptly paid, there was little that her erstwhile neighbors could do about it. For decades thereafter, the abandoned and ever-worsening ruin served as a vivid reminder of the miscalculation that Newport snobs had made in the summer of 1910.45

Perhaps ironically, it was another fire – this time at the Polo Grounds – that returned the Coogan name to the sports pages. In April 1911, an early morning blaze inflicted extensive damage upon the ballpark grandstand and bleacher sections. By that time, the majority owner of the New York Giants was John T. Brush, who had assumed the Polo Grounds/Manhattan Field lease when he acquired the club from Andrew Freedman in 1902. But before he invested the $100,000+ likely needed to repair the fire damage, Brush required the long-term security of a lease extension.46 Fortunately, his real property landlords were happy to oblige, and that May, Brush and Harriet Coogan executed a new 21-year lease on the Polo Grounds.47 The rent was $50,000 per year.48 Simultaneously, James Coogan announced that a $6 million amusement venue/amphitheater would be constructed on the vacated site of Manhattan Field.49 Nothing ever came of the project. Nor did New York Highlanders/Yankees owner Frank Farrell take Coogan up on the offer to relocate his club to the former Manhattan Field grounds.50

By 1915, James J. Coogan, ageing and suffering the effects of heart disease, had largely withdrawn from public life. In March, however, he reportedly tried to interest new Yankees owners Jacob Ruppert and Til Huston, whose American League club had been Polo Grounds sub-tenants of the Giants since 1912, in a proposal to build a new ballpark on the old Manhattan Field site. Coogan assured them that he could get Giants club president Harry Hempstead (son-in-law of the now-deceased John T. Brush and co-trustee of his estate) to go along with the proposition.51 Like the earlier amusement venue/amphitheater plan, the Coogan scheme came to naught. Seven months later, James Jay Coogan was dead, having passed away at the family residential suite at the Netherland Hotel in Manhattan on October 24, 1915.52 He was 70. Following a Solemn Requiem Mass concelebrated by Cardinal Terrence Farley at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and attended by dignitaries from the New York political and business worlds, the deceased was laid to rest in Calvary Cemetery, Woodside, Queens.

Upon her husband’s death, 54-year-old Harriet Coogan withdrew from society life. With her Ivy League-educated sons out of the house, she and unmarried daughter Jessie moved to smaller quarters in the midtown Biltmore Hotel. From then on, Harriet continued management of Gardiner-Lynch-Coogan real estate interests from offices in a family-owned Manhattan commercial building. On May 1, 1932, she and Charles A. Stoneham, the latest owner of the New York Giants, entered into a new 30-year lease.53 For the first 15 years, the annual rent would remain $50,000. After March 1947, it rose to $53,000/year. While the Giants continued as owners of the Polo Grounds ballpark, the lease contained a clause forfeiting – without compensation – ballpark ownership to the Coogan family upon a default in rent payment.54 The lease also prohibited the Giants from demolishing the venerable – but increasingly antiquated – Polo Grounds without the express consent of the Coogans.55

Meanwhile back in Newport, decades of Whitehall neglect finally provoked a public outcry. But even unflattering news articles syndicated nationwide left Harriet Coogan unmoved. She treated attempted press intrusion into her privacy with the same silent contempt visited upon the Newport swells. For its part, the press portrayed Harriet as an eccentric recluse, holed up with a spinster daughter in a tiny hotel suite that she only left late at night to go to her midtown office. Reportedly, Biltmore Hotel staff had not seen her in years, leaving a once-a-day meal outside her suite door. Still, the elderly Mrs. Coogan was described as invariably cordial when speaking to hotel staffers on the telephone or through a closed door. And she was a very generous tipper.56 Finally in 1946, eldest son Jay Coogan – his mother’s Newport enemies now long dead and with a court order looming – agreed to the razing of Whitehall.57

Old and infirm, Harriet Gardiner Lynch Coogan died in her bed at the Biltmore Hotel on December 18, 1947, surrounded by her four children. She was 86. Like her long-deceased husband, she was interred at Calvary Cemetery following a Funeral Mass celebrated at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The Coogan family connection to baseball, however, was not laid to rest with her. For the next two decades, Jay Coogan would oversee family interest in the Polo Grounds. Pursuant to the 30-year lease terms negotiated by his mother in 1932, the Giants continued to pay the $53,000 annual rent on the ballpark – even after the club left for San Francisco at the close of the 1957 season. Thereafter and without a pause in Polo Grounds rent checks, the now middle-aged Coogan children began receiving a monthly stipend from the New York Mets, as the expansion club was obliged to use the by then ancient and poorly maintained ballpark during the 1962-1963 seasons.58 At that point, the City of New York moved to condemn the Polo Grounds pursuant to the exercise of its eminent domain power. A bitterly fought courtroom battle between the city and the Coogans ensued. In the end, the City prevailed, but was obliged to pay the Coogan family $2,614,175, the court-assessed value of the real property on which the Polo Grounds had been built.59

By the time New York’s highest court settled the matter, the Polo Grounds was long gone, having been demolished in April 1964. And today, like the vanished North Manhattan ballpark, Polo Grounds real estate landlords James and Harriet Coogan are but a dim memory.

Acknowledgments

This joint profile was originally published in Base Ball: New Research on the Early Game, No. 12 (McFarland, 2021). This version was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Sources

Sources for the information contained herein are cited in the endnotes.

Notes

1 James’s siblings were Mary Anne (born 1856), Edward (1858), Thomas (1864), Margaret (1866), and Ella (1868).

2 When he stood for election to New York City political office, Coogan maintained that he was a native-born New Yorker. But the sworn passport application that he completed in June 1878 told a different story. Therein, Coogan averred that he had been born in Ireland, had been brought to this country at age seven, and was a naturalized US citizen.

3 See “Messrs. Coogan Brothers,” New York Times, June 7, 1885: 4.

4 Perhaps the best-known of the family properties is Gardiner’s Island, a private preserve located in the far-east part of Long Island Sound, and still owned by Gardiner family descendents.

5 Independent of his wife’s family wealth, William Lynch had amassed his own fortune, leaving an estate valued in the millions at the time of his death in 1884, as subsequently revealed in “Gives Millions to Daughter: Mrs. Lynch Transfers Her Estate to Mrs. Coogan to Avoid Inheritance Tax,” New York Evening World, April 30, 1900: 9.

6 According to nationally-syndicated gossip columnist Cholly Knickerbocker (Maury H.B. Paul) in “Mayfair’s Rich Recluse Owns Newport ‘Blot’; Scorns Wall Street,” Detroit Times, October 9, 1941: 77.

7 A year later, the Lynch-Coogan family alliance was further cemented by the marriage of Edward Coogan to Harriet’s sister Evelynn, with the nuptial rites again being performed at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. See “Married,” New York Times, June 22, 1884: 9.

8 The other Coogan children were Sarah Jessie (born 1886), W. Gordon (1888), and Gardiner (1892). Another child, born sometime after 1900 and name unknown, did not survive infancy.

9 See e.g., “Elevated Road Extension,” New York Times, May 10, 1887: 2, and “Objecting to a Viaduct,” New York Times, November 19, 1887: 8.

10 The original baseball tenants of the Polo Grounds were Day’s first team, the then-independent Metropolitan of New York club. The Mets were admitted to the major league American Association in 1883, while a second Day club, the New York Gothams (later Giants) entered the National League the same season. Both clubs played their home games at the Polo Grounds – occasionally simultaneously, as Day had constructed separate diamonds with grandstands in different corners of the ballpark. At the end of the 1885 season, however, the Mets were sold to amusement entrepreneur Eratus Wiman and relocated to Staten Island. Two seasons later, the Mets were disbanded.

11 Legally speaking, the New York Giants were owned and operated by the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, a closely-held corporation controlled by majority stockholder Day. The MEC’s three minority stockholders included Gordon, a Tammany Hall friend of Day and the figurehead president of the New York Mets. Although primarily a coal broker, the Manhattan-born Gordon had expansive knowledge of the island’s real estate and would later be appointed deputy commissioner of city buildings. Thereafter in 1903, New York Highlanders president Gordon was the one who uncovered the remote rocky mesa in Washington Heights on which Hilltop Park would be built.

12 Sources conflict regarding how the Gardiner-Lynch family obtained the real property that later became the site of the Polo Grounds. The long-prevailing view has been that the property had once been part of a large farm owned for generations by the Gardiner family and was passed down to Harriet Coogan by her maternal grandmother and mother. See e.g., “Great Estate Given Away,” Boston Herald, April 30, 1898: 8. Other sources contend that the Polo Grounds was constructed on 14 acres of Harlem River-reclaimed land purchased for $21,500 by William Lynch at an April 30, 1858 foreclosure sale. See e.g., Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006), 58. The narrative herein favors the latter view.

13 Per “The Candidacy of Coogan,” New York Times, September 23, 1886: 4, and “Mr. Coogan’s Ambition,” New York Times, September 3, 1886: 5.

14 See “Another Candidate for New York Mayor,” Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1888: 3; “A Campaign of Bread and Sugar,” Chicago Tribune, October 15, 1888: 2; and “Mr. Coogan Accepts,” New York Times, October 16, 1888: 5.

15 To the chagrin of present and future club owners, the elevation afforded excellent and free viewing of game action below. In time, thousands of freeloaders would take in NY Giants games from atop what was originally called Deadhead Hill. The appellation “Coogan’s Bluff” was coined by an unidentified New York Times reporter covering the 1893 Princeton-Yale football game. See “The Orange Above the Blue,” New York Times, December 1, 1893: 1.

16 New York Times, April 8, 1889: 8. An accompanying article explained that “the property referred to is a portion of the Lynch estate controlled by James J. Coogan,” and that a long-term lease could not be acquired because “the estate desires to sell this and the adjoining property.” Thus, Day was hoping for the intervention of “some capitalist … [to] purchase the two blocks of land … and give the [Giants] management a five or ten year lease.”

17 As reported in the New York Times, New York Tribune, and elsewhere, June 22, 1889.

18 Readers should understand that the New Polo Grounds and ballparks subsequently constructed on the adjacent plat were built and paid for by the owners of the New York Giants, and that these ballparks were the exclusive property of the club owners. The real property which lay beneath the ballparks, however, was owned by the Gardiner-Lynch family and had to be leased by Giants owners. When completed over the 1889-1890 winter, the New Polo Grounds was a handsome, if oddly pear-shaped, two-tiered enclosure with a seating capacity of about 14,000 for baseball, and far more for college football, track meets, harness racing, and other attractions that would later use the grounds.

19 See “An Offer for the Giants,” New York Times, September 6, 1889: 3. At the time, it was estimated that operation of the New York Giants (and Mets) had generated a $750,000 profit for the four-member Metropolitan Exhibition Company during its seven-season existence. That figure, however, seems implausible and may be a Times mis-print.

20 See “Leased for the Brotherhood,” Washington Post, September 29, 1889: 1. The lease was for 10 years, at $24,000 per annum.

21 See “Day in Hard Luck Again,” Chicago Tribune, February 4, 1890: 6, and “Mr. Day’s Voice Still for War,” Chicago Tribune, February 5, 1890: 6. Both Tribune articles stated that Coogan was “financially interested” in the New York Players League franchise, but no evidence of any such Coogan interest was discovered by the writer. As with other Coogan matters, his motives for pressuring Day are unknown.

22 Sporting Life, April 5, 1890.

23 See “To Start a New Park,” Washington Post, November 8, 1891: 6.

24 After the National League and Players League New York Giants franchises consolidated in September 1890, Manhattan Field was sublet to the Manhattan Athletic Club. Freedman’s interest in the Giants stemmed from his subsequent court appointment as receiver for the financially failing MAC. When Freedman gained control of the Giants franchise in January 1895, he assumed the leases for both the Polo Grounds and adjoining Manhattan Field. The dual ballpark leases cost Freedman between $20,000 to $25,000 per year. At the March 1900 National League owners meeting, his fellow magnates agreed to reimburse Freedman the annual cost of the Manhattan Field rental as part of their efforts to appease the Giants boss in the aftermath of the Ducky Holmes affair.

25 See e.g., “Business Troubles,” New York Times, January 12, 1894: 11, memorializing a $12,586.36 judgment entered against James J. Coogan and Edward V. Coogan for unpaid business advertising.

26 See “Coogan Is Bankrupt,” New York Times, January 1, 1894: 2. Coogan’s financial distress did not affect the Gardiner-Lynch family fortune, as Sarah Gardiner Lynch had always segregated her family’s business interests from those of her son-in-law.

27 As the mother of Edward’s late wife Evelynn, Sarah Lynch was also Edward Coogan’s mother-in-law.

28 See “J.J. Coogan’s Brother Sues Him,” New York Sun, December 1, 1898: 29; “He Charges Conspiracy,” New York Times, December 1, 1898: 3.

29 See e.g., “Great Estate Given Away,” Boston Herald, April 30, 1900: 8; “Escapes Inheritance Tax,” New Haven (Connecticut) Register, April 30, 1900: 5; “Millions for Mrs. Coogan,” New York Times, April 30, 1900: 11. At the time, the value of the property titled over to Harriet was placed in the $15 million-to-$25 million range. In consideration for the transfer of the family wealth, Harriet supposedly gave her mother $2.

30 “Change Not Likely,” Sporting Life, August 19, 1899: 6.

31 See “New Borough President,” New York Times, January 6, 1899: 12. The position of borough president was a newly-created office, devised after Brooklyn, Queens, the east Bronx, and Staten Island were incorporated into New York City in 1898.

32 See “President Coogan’s Eligibility,” Washington Post, December 18, 1900: 8.

33 The previous May, a $100,000 contribution to the campaign chest of likely Democratic Party presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan had briefly fueled rumor that Coogan was angling for the VP spot on the ticket. See “Coogan’s Alleged Gift,” New York Times, May 27, 1900: 2, and “$100,000 for Bryan,” Washington Post, May 27, 1900.

34 See e.g., “The Real Estate Market,” New York Sun, April 10, 1903: 13; “Million Dollars’ Worth of Flats,” New York Evening World, May 16, 1903: 4; “Mrs. H.G. Coogan’s Venture,” New York Times, May 17, 1903: 20.

35 As reported in the Pawtucket (Rhode Island) Times, June 29, 1903, New York Times and New York Tribune, June 30, 1903, and elsewhere.

36 Previously, the Coogans had summered at Narragansett, another Rhode Island resort. But a new family vacation home was sought after Harriet was accosted by thugs and robbed of jewelry in Narragansett Pier.

37 See e.g., “The News of Newport,” New York Times, November 22, 1903: 9; “Mrs. Grosvenor Has Most Blues,” Boston Herald, September 6, 1905: 5; “Social Notes from Newport,” New York Tribune, September 7, 1907: 7; “Snapshots of Social Leaders,” Washington Post, September 8, 1909: 7.

38 See e.g., “This Is No Coogan’s Bluff, Says Mrs. Coogan to Newport,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 6, 1932: 33; Charles Goddard, “Last of Mrs. Coogan’s Long Vengeance,” syndicated in the Detroit Times, June 9, 1946: 71; The (Portland) Oregonian, June 9, 1946: 55; and elsewhere.

39 Even a century later, the Gardiner family patriarch would dismiss the Newport elite and their ilk as “nouveaux riches.” See Robert F. Worth, “Robert D. L. Gardiner, 93, Lord of His Own Island, Dies,” New York Times, August 24, 2004: B7. For more on the pretensions and prejudice of the Newport elite, see Anne DeCourcy, The Husband-Hunters: American Heiresses Who Married into the British Aristocracy (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2017), 105-118.

40 Harriet Coogan was also independently wealthy, polished, a stylish dresser, and exceptionally good-looking. But the extent, if any, to which dowdy Newport high society matrons were personally jealous can only be speculated upon.

41 Years later, the event was described as a coming-out party for Jessie Coogan. By then, however, Harriet’s 24-year-old daughter was well past the debutante stage and had been out in society since at least 1906. See “Buds to Make Their Bow,” Kansas City Star, October 3, 1906: 9.

42 As per the articles cited in endnotes 5 and 37, above. See also, Inez Cooper, “Mrs. Coogan’s (of Coogan’s Bluff) Strange Revenge,” San Francisco Examiner, October 12, 1941: 85.

43 Same as above. See also, “Milestones,” Time, December 29, 1947, and “Necrology,” The Sporting News, December 31, 1947: 23.

44 See “Newport Home Burns,” New York Times, March 11, 1911: 9.

45 See again the newspaper articles cited in endnotes 38 and 42.

46 By April 1911, Brush had suffered from the wasting disease locomotor ataxia for years and was concerned about the financial security of second wife Elsie and teenage daughter Natalie after his passing.

47 As reported in “Two New York Parks,” Sporting Life, May 13, 1911: 1. See also, “Brush Says Polo Grounds Will Stay,” Springfield (Massachusetts) News, May 5, 1911: 6; “Long Lease on Polo Grounds Signed,” (Boise) Idaho Statesman, May 14, 1911: 9.

48 As revealed after the will of the late John T. Brush was admitted to probate. See “Giants Money Making Club,” Springfield News, January 1, 1915: 17; and “NY Giants Paid $470,000 Profits in Three Years,” Colorado Springs (Colorado) Gazette, January 1, 1915: 7.

49 See “Plan $6,000,000 Park at Coogan’s Bluff,” New York Times, May 6, 1911: 7; “Ninety Acres for Big Park,” Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, May 7, 1911: 2; “Will Seat 50,000 Fans,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 10, 1911: 10.

50 See again, “Two New York Parks,” Sporting Life, May 13, 1911: 1. See also, “Rival Friends,” Sporting Life, April 13, 1912: 5. Manhattan Field had been demolished in 1903. Instead of taking up Coogan’s offer, Farrell persevered with a boondoggle ballpark construction project in the Knightsbridge section of the Bronx that drained his finances and eventually precipitated the sale of the franchise to Jacob Rupert and T.L. Huston in January 1915.

51 See Joseph Vila, “The Ground Question in New York,” Sporting Life, March 3, 1915: 1. Brush son-in-law Hempstead had assumed leadership of the Giants franchise shortly after Brush’s death in November 1912.

52 “James J. Coogan Dead,” New York Times, October 25, 1915: 25. The cause of death was given as heart disease.

53 For contract purposes, the lessee was the National Exhibition Company, the NY Giants corporate alter ego.

54 Reputedly, Harriet Coogan did not trust the mail and appeared at the NY Giants mid-town office each month to collect the Polo Grounds rent check in person, per Michael Pollak, “The Man Behind the Bluff,” New York Times, April 25, 2004: CY2.

55 The terms of the Polo Grounds lease became public during litigation instituted by Harriet Coogan’s heirs after New York City condemned the ballpark in the early 1960s. A comprehensive overview of the litigation is provided by John Hogrogian in “The Polo Grounds Case: Parts I and II,” The Coffin Corner, Vol. 11, No. 6, and Vol. 12, No. 1 (1989).

56 As recounted in extensive and sometimes dubious detail in the circa 1932-1946 newspaper articles and features cited previously. Much of this reportage was dismissed as contrived or hyperbole by her sons when Harriet Coogan died in December 1947. “Mother was not a recluse,” maintained son Gardiner. “She withdrew because of her age and infirmity. She was a gracious person who handled everything with perfect amicability,” per “Mrs. Coogan Dies; Large Landholder,” New York Times, December 19, 1947: 26.

57 Per the Newport (Rhode Island) Mercury and Weekly News, December 26, 1947: 7. The Whitehall grounds, however, remained Coogan family property and stayed unimproved until sold in 1953.

58 See again, Hogrogian, The Coffin Corner, above.

59 See Matter of City of New York v. Coogan, 20 N.Y.2d 618, 233 N.E.2d 113 (Court of Appeals, 1967). See also, “Sarah Coogan, Member of Polo Grounds Family,” the obituary for S. Jessie Coogan, age 94, published in the New York Times, March 7, 1979: A22. The San Francisco Giants were awarded $1,724,714 for improvements made to the Polo Grounds over the years of its tenure there.