April 11, 1895: Scrappy Page Fence Giants fall to Cincinnati Reds in preseason exhibition

Using an apparatus they’d devised themselves, industrious J. Wallace Page and his younger cousin, Charles Lamb, began manufacturing woven wire fencing in the 1880s as a low-cost, livestock-friendly alternative to barbed wire.1 By 1894 their business had grown into a thriving enterprise, the Page Woven Wire Fence Company, with 100 employees manufacturing fencing for farms and businesses nationwide in a 25,000-square-foot factory in Adrian, Michigan.2

Using an apparatus they’d devised themselves, industrious J. Wallace Page and his younger cousin, Charles Lamb, began manufacturing woven wire fencing in the 1880s as a low-cost, livestock-friendly alternative to barbed wire.1 By 1894 their business had grown into a thriving enterprise, the Page Woven Wire Fence Company, with 100 employees manufacturing fencing for farms and businesses nationwide in a 25,000-square-foot factory in Adrian, Michigan.2

Emphasizing the safety and effectiveness of woven wire, Page employed a wide variety of marketing strategies to sell his fencing, like demonstrations of wire withstanding impacts from farm machinery. He also created a zoo on company grounds in which deer, wolves, sheep, and other animals were penned inside woven wire fencing enclosures.3

The summer of 1894 was a particularly prosperous time for the company commonly known as Page Fence. Expenditures for the coil steel they used to make fencing had been dropping for years, and steep tariffs on imported steel wire from the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act had sales booming – enough to help fund construction of a new two-story building.4 Flush with financial success, Page was receptive when local businessmen, together with an Ohio ballplayer with an eye for opportunity, approached him with the idea of financing a traveling baseball team.

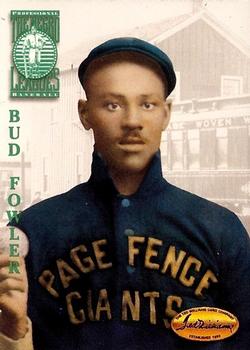

Bud Fowler, “[b]aseball’s itinerant vagabond,”5 had come to Adrian in August 1894 as the field manager and second baseman for the integrated Findlay (Ohio) Sluggers, to play a pair of contests with a local nine. Planning to form a new all-Black team for 1895, Fowler was so impressed by the turnout for the Sluggers’ opening game with the Adrian Light Guard that he offered to base his new club in Adrian if the townspeople “will guarantee him $500 and fix up good grounds.”6 With that level of backing, Fowler told the Adrian Evening Telegram, he could “get a team equal to the famous [New York] Cuban Giants.”7

Within days local investors stepped forward to provide funding, most prominently J. Wallace Page. Dubbed the Page Fence Giants after their principal benefactor, the team went from town to town with the Page Fence name emblazoned not only across their uniforms, but also on the custom-made railroad sleeping car that they traveled in.

“The organization of the colored base ball club for the season of 1895, with management and headquarters in this city, is a settled fact,” announced the Telegram on September 21, 1894. “Thirteen of the finest ball players in the country have already been secured,” the story continued, adding that “[e]very other member of the club will be of the same high grade, of equal or even more distinguished professional renown” as Fowler and Grant “Home Run” Johnson, who reportedly hit 60 home runs for Findlay in 1894.8

Within weeks of the announcement, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that Fowler had arranged for the Giants to tour “the Western states,” including an agreement to play two games in Cincinnati against that city’s National League club, the Reds.9

Tenth-place finishers in the NL in 1894, Cincinnati had reason to expect improvement in the coming season. Gone was former captain and manager Charlie Comiskey, replaced by longtime stellar backstop Buck Ewing, whom Reds owner John T. Brush credited with having “as thorough and complete a knowledge of baseball as any man living.”10

After a week of practice in the central Indiana town of Marion, the Giants played their first game on April 10 against the Western League Indianapolis Hoosiers.11 The Page Fence company had spent months promoting the team, giving out to potential customers “handsome calendars” and advertising cards adorned with images of its ballplayers.12 Facing an Indianapolis starting lineup that included eight former or future major leaguers, the Giants were “waxe[d],” 26-1.13

As the Reds headed into their first contest with the Giants, the Maysville (Kentucky) Bulletin reported that “[t]he Cincinnati Club under Captain Buck Ewing’s management has made a splendid showing in the exhibition games this spring, and promises to cut quite a figure in the League race this year.”14 The Reds had every reason to be confident of victory over the Page Fence nine – they had trounced Indianapolis, 14-2, just a few days before that team had embarrassed the Michiganders.15

Ewing tabbed Tom Parrott as his starting pitcher, a talented but temperamental two-way player, who had won 17 games the year before while hitting .323 – despite twice getting suspended for refusing to pitch.16 Suffering from an unspecified illness the day before this game, Parrott “knocked out the old malaria by the copious use of quinine and whisky,” according to the Cincinnati Enquirer.17 Opposing Parrott for the Giants was Joe “Cannon Ball” Miller, touted in 1890 as holding an amateur strikeout record, with 22 punchouts in a nine-inning Nebraska League game. Miller had spent 1894 with a pair of Iowa-based integrated teams, the Dubuque Whites and the Council Bluffs Maroons, where he was known as the “colored cyclone.”18

No attendance figures appear in the two known newspaper accounts of this game, but both describe a large contingent of Black fans on hand at League Park, cheering for the Giants. Said the Cincinnati Enquirer, “[E]very member of the local colored population who could get off yesterday afternoon was on the seats at the Cincinnati Park when time was called for the game.”19 The Cincinnati Post estimated that there were “enough distinguished gentlemen of color … in … the stands to equip a full score of [military] companies.”20

After two frames of scoreless action, the Giants “pounded in” two runs in the third inning “off the curves of the erratic Tom Parrott,”21 thanks to successive singles by right fielder George Hopkins, catcher Peter Burns (both last with the Chicago Unions), Miller, and first baseman George Taylor, who had played with Miller for both Dubuque and Council Bluffs.22

An inning later, Cincinnati touched up Miller for three tallies. After a walk to center fielder Bug Holliday, the centerpiece of Cincinnati’s 1894 offense,23 left fielder Billy Hoy “cracked out a beauty to deep center” for three bases, scoring Holliday.24 Shortstop Germany Smith, Cincinnati’s 36-year-old elder statesman, next grounded to third baseman William Malone. Malone threw home, hoping to cut Hoy down at the plate, but the ball never got there. It hit Cincinnati’s deaf left fielder in the back, allowing him to score. One out later, rookie right fielder George Hogriever singled to bring Smith home.

In the fifth, a single by ironman Bid McPhee,25 an error by Taylor, walks to Smith and catcher Bill Merritt, and hits by Hogriever and Parrott gave the Reds another five runs.

Down 8-2, the Giants scored three times in the top of the sixth. Consecutive one-out singles by center fielder Gus Brooks (yet another Chicago Unions alumnus), Malone, and left fielder John Nelson, a former New York Cuban Giant, brought Brooks home and set the stage for the controversy that was to follow. Hopkins hit a comebacker to Parrott that the hurler threw to first, after which rookie first baseman Harry Spies fired the ball to third in time to cut down Malone. Or so the Reds thought. Umpire Jack Sheridan called him safe. A single by Burns scored Malone and Nelson, pulling the Giants to within three.

Miller proved unable to keep the Reds at bay in the bottom of the inning. Singles by Spies and Holliday and Hoy’s double scored two to put Cincinnati ahead 10-5.

The Giants drew two runs closer in the top of the seventh but gave one back in the bottom of that inning. How those runs scored was left unreported. At some point in that inning or the eighth, Fowler replaced Miller with 21-year-old Billy Holland, who had made his professional debut a year earlier with the Chicago Unions.26

Neither side plated another run over the final two innings, making the final score 11-7.

An anonymous Cincinnati Enquirer sportswriter called the game a great one, and lavished praise on the Giants for “put[ting] up a scrappy game of ball.” “Bud Fowler, the veteran, had got together a great team of players,” the writer gushed, adding, “They will win more games than they will lose.” Brooks, who fielded gloveless as most of the Giants did, was hailed for “three wonderful catches” and Malone for “playing in good style.”27 Malone and Burns were credited with being “good coacher[s],” presumably for their work as base coaches. Believing Fowler to be 47 years old (he was actually 10 years younger), that same writer marveled how the Giants’ organizer wore his age “like a young blood.”28

The two teams met again the next day in a game that proved to be no contest. Cincinnati scored 11 first-inning runs on the way to a 16-2 triumph.29

Cincinnati swept Cleveland in its NL season-opening series in late April but Holliday contracted appendicitis soon after and was lost for much of the year.30 Left with an offense that was only average, the Reds finished the year at 66-64-2.

The Giants went on to play 156 games in 112 towns across seven states, compiling a record of 118-36-2.31 They finished the year with Sol White at the helm, a player-manager brought on in July from the Western Interstate League, after a dispute with J. Wallace Page and his partners drove Fowler to jump to the integrated Adrian team of the Michigan State League.32

The Page Fence Giants remained arguably the top Black baseball team through the 1898 season, after which J. Wallace Page reluctantly pulled his sponsorship and the team dissolved. Struggling to obtain the wire that his business depended upon from the “iron and steel trust,” later US Steel, Page needed to shepherd the company’s resources in order to stay afloat.33 The Page Wire Woven Fence continued producing wire fencing until 1919, when it was absorbed into a successor business.34 More than 100 years later, “page wire” has come to be a generic term used to describe woven wire mesh fencing, regardless of manufacturer.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Gary Belleville and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Photo credit: Bud Fowler, Page Fence Giants, Trading Card Database.

Sources

In addition to the Sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Mitch Lutzke’s The Page Fence Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2018) and the Seamheads.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Stathead.com websites.

Notes

1 “Woven Wire Won!” Adrian (Michigan) Weekly Press, December 13, 1891: 31.

2 “Wire Fences,” Adrian Weekly Press, November 2, 1894: 6. Adrian is about 70 miles southwest of Detroit.

3 “Page Woven Wire Fence,” Cassopolis (Michigan) Vigilant, February 25, 1892: 4; “Local Items,” Lake Geneva (Wisconsin) News, August 23, 1894: 5; “A Pleasing Zoological Collection,” Adrian Weekly Press, September 4, 1891: 2.

4 Douglas A. Irwin, “How Did the United States Become a Net Exporter of Manufactured Goods,” Working Paper 7638, National Bureau of Economic Research, April 2000, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w7638/w7638.pdf; Waterville (Kansas) Telegraph, August 24, 1894: 2; “The Week,” Adrian Weekly Press, August 31, 1894: 3.

5 Mitch Lutzke, The Page Fence Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2018), 24.

6 $500 in 1895 was equivalent to approximately $19,000 in 2025, according to the CPI inflation calculator at https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1895?amount=500.

7 “Base Ball Talk,” Adrian Evening Telegram, August 31, 1894: 3.

8 “Page Fence Giants,” Adrian Evening Telegram, September 21, 1894: 3; Phil Williams, “Grant ‘Home Run’ Johnson,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/grant-johnson/.

9 “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 5, 1894: 2; “Baseball Notes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 22, 1894: 2.

10 “Hooray!” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 15, 1894: 2.

11 “The Giants,” Marion (Indiana) Leader, April 3, 1895: 5; “The Giants Mowed Down,” Indianapolis Journal, April 11, 1895: 3. A high-level minor league formed in November 1893 with Ban Johnson as president, the Western League evolved over the next few years to become the American League. The Giants’ debut was originally scheduled for April 9, but wet grounds pushed their inaugural game to the next day. “The League Organized,” Kansas City Journal, November 22, 1893: 2; “Ball and Bat,” Adrian Evening Telegram, April 10, 1895: 3.

12 “The Week,” Adrian Press, January 18, 1895: 9. Framing team members as respectable, the Marengo (Illinois) Republican pointed out that several were college graduates, none were “addicted in any degree to strong drink, and only two use tobacco.” “Colored Base Ball Club,” Marengo (Illinois) Republican, January 18, 1895: 8.

13 “The Giants Mowed Down,” Indianapolis Journal, April 11, 1895: 3.

14 “Base Ball,” Maysville (Kentucky) Bulletin, April 11, 1895: 3. The Reds held their training camp in Mobile, Alabama.

15 “Sporting,” Dayton (Ohio) Herald, April 8, 1895: 3.

16 Mark Armour, “Tom Parrott,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Tom-Parrott/, accessed July 3, 2025. Parrott’s second suspension came the day after he had hit for the cycle while playing second base.

17 “Some Hot Swipes,” Cincinnati Post, April 10, 1895: 9; “’Come Seven,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 12, 1895: 2.

18 “All About the Amateurs,” Omaha Bee, August 3, 1890: 9; “Maroons Win Out,” Freeport (Illinois) Bulletin, August 3, 1894: 1; “Twice Winners,” Waterloo (Iowa) Courier, September 5, 1894: 3; “They Found More Woe,” Cedar Rapids Gazette, September 25, 1894: 8; “Will Go Against the Huskers,” Council Bluffs (Iowa) Nonpareil, September 11, 1894: 5; “Prominent Baseball Figure of Early Days Is Bluffs Visitor,” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, May 12, 1949: 20.

19 “’Come Seven.”

20 “Crap Fiends’ Joy,” Cincinnati Post, April 12, 1895: 4. In its highly bigoted recounting of the game, the Post claimed that “Every son of Ham was a rooter of the Page Fence Giants,” referring to the biblical figure that some Christians fundamentalists consider the ancestor of all Africans. “Crap Fiends’ Joy,” Cincinnati Post, April 12, 1895: 4.

21 “Crap Fiends’ Joy.”

22 “Prominent Baseball Figure of Early Days is Bluffs Visitor,” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, May 12, 1949: 20; “A Great Record,” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, August 28, 1894: 8.

23 A former American Association (1889) and NL (1892) home run leader, Holiday led the 1894 Reds in hits, RBIs, batting average and slugging percentage and was tied with Jim Canavan for the most home runs, with 13. That home-run total, as well as his .376 batting average and 123 RBIs (in 123 games), were each in the top 10 across all NL hitters.

24 “’Come Seven.”

25 Between 1884 and 1894, McPhee played in 1,406 games, more than any other major leaguer over that span. Across his 18-year career, spent exclusively in a Cincinnati uniform, McPhee appeared in 2,129 games at second base, a club record that remains unmatched through the 2024 season.

26 See, for example “Schroders Win from Unions,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 21, 1894: 11, and “Brunette Ball Team Wins,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 7, 1894: 11.

27 “’Come Seven.” Only Burns, behind the plate, and Taylor at first base wore gloves for the Giants. By the end of the 1880s, many major leaguers wore gloves. Cincinnati second baseman Bid McPhee was one of the last to don a glove, not doing so until 1896. Jim Daniel, “#Goingdeep: The Evolution of Baseball Gloves,” Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/discover/going-deep/the-evolution-of-baseball-gloves, accessed July 3, 2025; Ralph Moses, “Bid McPhee,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bid-mcphee/, accessed July 3, 2025.

28 “’Come Seven.”

29 “Slaughtered,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 13, 1895: 2. Cincinnati’s winning pitcher, Frank Foreman, was one of a few ballplayers to play in four major leagues: the Union Association, American Association, National League, and American League.

30 “‘Bug’ Holliday Is Very Ill,” Boston Globe, April 26, 1895: 9.

31 Bruce Markusen, “Page Fence Giants Succeeded On and Off the Field,” Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/discover/Page-Fence-Giants-succeeded-on-and-off-the-field, accessed May 20, 2025.

32 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994), 836; Brian McKenna, “Bud Fowler,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bud-fowler/. Burns, Miller and 19-year-old George Wilson, a southpaw pitcher and Adrian native who did not play in the April 11-12 Reds games, joined Fowler in leaving the Giants for the Adrian team.

33 The Page Fence Giants, 227.

34 “Border Cities Wire and Iron Ltd. Observes Anniversary in 1951,” Windsor (Ontario) Star, December 30, 1950: 3-10.

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Reds 11

Page Fence Giants 7

League Park

Cincinnati, OH

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.