August 16, 1927: Babe Ruth’s homer reaches the roof at Comiskey Park in Chicago

During the 1926 American League season, there were a handful of instances where the capacity of Comiskey Park in Chicago was exceeded by the demands of the public, usually when the New York Yankees came to town.1 In these situations, the excess attendees were allowed onto the playing field and rather ineffectively roped off from the action. These situations bruised the sensitivities of White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, who decided to open his pocketbook, and build a second deck atop the outfield stands. Comiskey hired noted Chicago architect Zachary Taylor Davis to make the improvements. The old wooden stands would be removed; the new, modern double-deck structure would be built with concrete and steel, and cost $600,000.

During the 1926 American League season, there were a handful of instances where the capacity of Comiskey Park in Chicago was exceeded by the demands of the public, usually when the New York Yankees came to town.1 In these situations, the excess attendees were allowed onto the playing field and rather ineffectively roped off from the action. These situations bruised the sensitivities of White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, who decided to open his pocketbook, and build a second deck atop the outfield stands. Comiskey hired noted Chicago architect Zachary Taylor Davis to make the improvements. The old wooden stands would be removed; the new, modern double-deck structure would be built with concrete and steel, and cost $600,000.

The additional seating would increase the park’s capacity from 28,000 to 52,000. This was an amazonian leap in optimism, considering that the franchise had topped 800,000 in a season only twice in its 26-year history. The roof above the second tier would be 75 feet above the playing surface, offering shelter to the fans, but giving the park a cavernous, enclosed look. “Well, nobody is going to hit the ball over those stands,” Comiskey chirped.2

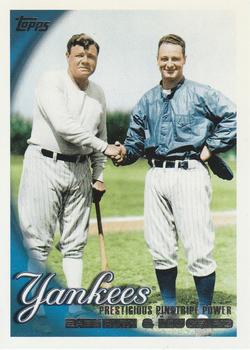

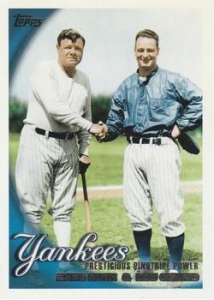

Was Comiskey’s statement an offhand remark, or was it a challenge? He certainly wasn’t speaking to his own hitters. The 1926 White Sox had hit only 32 home runs as a team. Outfielder Bibb Falk, with 12 homers in 1922, was the only active White Sox player who had ever hit more than 10 in a season. But with Babe Ruth of the Yankees, this was a much different story. The Sultan of Swat, at age 32, was still in his prime, having cranked out 47 homers the previous season, many of them prodigious clouts. Including the 60 homers he would hit in 1927, he had 358 more round-trippers left in his tank.

On Tuesday, August 16, 1927, the New York Yankees came to Chicago to start a four-game series with the White Sox. An estimated 20,000 fans were in the seats, an especially good gate for a Tuesday, or most any day, at Comiskey Park in the 1920s. There was nothing “crucial” about the game. New York was running away from the rest of the league, playing .705 ball with a 79-33 record. The Washington Senators were the nearest competitor, 13 games back. The White Sox were ensconced in fifth place, 25½ games out.

But the game was the undercard. Lou Gehrig, eight years younger than Ruth, was coming into his own as a slugger. Gehrig had already amassed 38 home runs this season, two more than Ruth. The public was keenly aware both that Gehrig might top Ruth for the season, and that the two men together were likely to set a number of marvelous records. And then there was that roof, staring them in the face.

The Yankees’ pitching opponent on this day was Alphonse “Tommy” Thomas, a 5-foot-10, 175-pound righty noted for a fastball that worked the corners of the plate.3 Thomas had been acquired by the White Sox from the International League’s Baltimore Orioles for $15,000 after the 1925 season.4 Now he was establishing himself as a major component of the White Sox staff. Thomas was coming off a tough 2-1, 10-inning loss at Cleveland five days earlier. Nonetheless, he was having a good season with a 14-11 record and a 2.95 ERA. Although two of the current White Sox moundsmen, Red Faber and Ted Lyons, were future Hall of Famers, Thomas, in 1927, may have been the most effective of the bunch.5 Thomas would end the season with a 19-16 record, a team-leading 40 starts, and a 2.98 ERA.

Despite Thomas’s general success in 1927, he was not solving the Yankees’ batters all that well. Thomas had faced the Yankees twice and lost both games, dropping a 4-1 decision on June 7, then losing again, 3-2, on July 24. In both games, Thomas’s undoing was the home-run ball. On June 7 Gehrig, Pat Collins, and Ruth had gone deep, Ruth’s blast to deep center being his 18th of the season. And in the July game, the Babe had smacked his 31st, this time to right.

The game itself had little intrigue after three innings. Earle Combs’ triple and a double by Bob Meusel, the first of his four hits in the game, led to two runs for the Yankees in the top of the first. Ruth got on base with a walk, but later was tagged out at the plate on a fielder’s choice. The White Sox tried to retaliate in their half, loading the bases with one out on a hit batter, a walk, and a single. When White Sox left fielder Bibb Falk flied to left, Ray Flaskamper tried to score from third, but Ruth, this time the aggressor, gunned him down at the plate — an inning-ending double play.

The Yankees were at it again in the third: Ruth walked, Gehrig doubled, and both came home on a pair of fly balls, making the score 4-0. With Yankees star pitcher Herb Pennock firing off the mound against a weak White Sox offense, there was little doubt, or surprise, about the game’s outcome. But the game itself was not what had brought out all those fans on a weekday afternoon.

Both pitchers sailed through the fourth inning, but Thomas had the heart of the Yankees order to face again in the top of the fifth. Ruth led off the inning, having already walked in his first two at-bats, but this time Thomas threw him a pitch he liked, a high fastball.6 The ball flew off the bat, heading well above Comiskey’s insurmountable roof in right field. It cleared the outfield wall, 360 feet from home plate, then the roof, landed in a parking lot, and bounced off, eastwardly, toward what today is the Dan Ryan Expressway. Thomas retained enough composure to deliver a called third strike to Gehrig, and got through the rest of the inning without further damage. And Ruth now had 37 homers, only one fewer than his teammate, Gehrig.

When catcher Moe Berg led off the White Sox fifth with a double, Chicago manager Ray Schalk saw it as a propitious time to remove Thomas from the game for a pinch-hitter, Bernie Neis, who grounded out.7 The inning came to a close with Berg still parked on second. Bert Cole came in to pitch the last four innings for the home team, giving up three more runs in the eighth but no homers. The White Sox strung together three hits in the seventh to score a token run, making the final score 8-1. The Yankees plodded on, taking the next two games, before Chicago won the finale on Friday, 3-2. Ruth homered again in the Wednesday game, Gehrig in the loss on Friday. The Yankees left town with Gehrig maintaining his one-homer lead over Ruth, 39-38.

But Gehrig’s power binge was about to stall out; he hit only two more homers in August, then six in September, finishing with 47. Ruth, meanwhile, hit five more round-trippers in August, then went ballistic with his record 17 homers in September, to finish at 60. The two teammates — Ruth and Gehrig — had hit a record 107 homers in a season that lasted until 1961 when two other Yankees, Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, combined for 115.

And then there was that roof. Comiskey’s edifice remained unsullied again until May 4, 1929, when Lou Gehrig homered off Urban Faber. Over the next 20-plus years, other American League sluggers — Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg, and Ted Williams — also recorded “roof shots,” but it was not until April 25, 1951, that a White Sox player, first baseman Eddie Robinson, was successful in topping the structure.

The last game at Comiskey Park was played on September 30, 1990. In its 64-year history, the roof had been violated 22 times by White Sox batters, 14 times by opponents.8 Ron Kittle, with seven roof shots, and Greg Luzinski with four — all in the mid-1980s — were the most prolific White Sox sluggers to reach the roof.9 Ted Williams and Jimmie Foxx were out-of-towners who found the roof twice.

Interestingly, for both Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, the roof shot was a one-and-done. Both men, but especially Ruth, would seem to have been capable of reaching the roof multiple times — but chose not to. It was as if these men were saying to Comiskey, “Okay, Charley, you have your roof, we made our point; now let’s get on with the game.”

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

1 Estimated attendances from Baseball-Reference.com box scores show five 1926 Comiskey Park games with attendances of 30,000 or more, including the June 20 game with New York, when 40,000 showed up.

2 Michael Benson, Ballparks of North America (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 1981), 91.

3 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside Books, 2004), 402-403.

4 Jimmy Keenan, “Tommy Thomas,” SABR Biography Project, sabr.org.

5 Baseball-Reference.com lists Thomas as the third-highest American League player in Wins Above Replacement with 8.0, trailing only Ruth (12.4), Gehrig (11.8), and teammate Ted Lyons (8.1).

6 John G. Robertson, The Babe Chases 60 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 1999), 103.

7 Thomas continued to have great difficulty with Ruth throughout his career. Ruth batted .458 against Thomas with a 1.529 OPS, including 10 home runs. Other pitchers gave up even more homers to Ruth, Rube Walberg leading the list with 14.

8 It should be noted that a “roof shot” includes any home run that made it onto the roof, not necessarily beyond it. Assuming that each of the upper deck’s 20 rows was 2½ feet deep, considering both the seat and the foot space, the back edge of the roof would be at least 50 feet beyond the front. That Ruth’s drive completely cleared the roof on the fly puts it in a stratum well beyond many other recorded “roof shots.”

9 Richard C. Lindberg, Total White Sox (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006), 635-636. The book notes that home plate at the stadium had been moved eight feet closer to the outfield wall during the Kittle-Luzinski era.

Additional Stats

New York Yankees 8

Chicago White Sox 1

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.