August 22-24, 1948: The Negro Leagues East-West All-Star Games

Overview

The origins of the Negro League All-Star Game date from 1933 when sportswriters Roy Sparrow of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph and Bill Nunn of the Pittsburgh Courier championed the idea. Not coincidentally, their brainchild surfaced around the same time as the inaugural major-league All-Star game, which was to be held at Chicago’s Comiskey Park in conjunction with the 1933 World’s Fair. A series of events guided by Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords and president of the Negro National League, resulted in a deal with Robert “King” Cole, the owner of the Chicago American Giants, to lease Comiskey Park for the first East-West All-Star Game, to take place on September 10.1

The origins of the Negro League All-Star Game date from 1933 when sportswriters Roy Sparrow of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph and Bill Nunn of the Pittsburgh Courier championed the idea. Not coincidentally, their brainchild surfaced around the same time as the inaugural major-league All-Star game, which was to be held at Chicago’s Comiskey Park in conjunction with the 1933 World’s Fair. A series of events guided by Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords and president of the Negro National League, resulted in a deal with Robert “King” Cole, the owner of the Chicago American Giants, to lease Comiskey Park for the first East-West All-Star Game, to take place on September 10.1

The 1933 game kicked off an amazing run of contests that paralleled — and sometimes outdrew — the games of their white major-league counterparts. Single all-star games were played through the 1938 season; later, tandem games were played in 1939, 1942, 1946, 1947, 1948, and 1958. Even as the Negro Leagues began their decline in the wake of Organized Baseball’s integration, the East-West All Star Game continued to be an annual event until 1962.2

According to author Larry Lester, “[T]he span beginning in 1933 and ending in 1953, alpha to omega, Genesis to Revelation, signals the most celebrated period in black baseball history.” Then “the demise of the black leagues became predictable, as the younger talented blacks were soon signed into the former white leagues. By the mid-1950s, the [Negro] leagues went from show time to burlesque. They had become a circus. …”3 The last Negro League-sanctioned All-Star Game was held in 1961; the final game was played in 1962, the year the Negro American League was shuttered for good.

According to Baseball-Reference.com, “Thirty-six games were played in the 30 consecutive seasons that the game was active. Twenty-eight games were played at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, four at New York’s Yankee Stadium, while one each were played at New York’s Polo Grounds, Washington’s Griffith Stadium, Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium and Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium. Some of the East-West Games held outside of Comiskey Park were not consistently referred to in the media as the East-West Game — for instance, the eastern matches from 1946-1948 were officially called the ‘Dream Game,’ though some outlets referred to them as East-West Games.”4

The 1948 East-West All-Star Games: The Players

On July 31, 1948, the Chicago Defender announced the selection of the players for the All-Star Game: three from each team in the two six-team leagues. The Defender wrote, “[T]he Negro American League club owners have decided on the players who will represent them in the 16th Annual East v. West game to be played at Comiskey Park, Sunday afternoon [August 22, 1948]. … A second game between the East and West teams, called the ‘Dream Game’ will be played in New York that week [August 24, 1948].”

Most previous teams were selected by vote of the leagues’ fans, but, wrote the Defender, “The Negro National League voted against this method, preferring to make their own selections.”5 On August 15 the Chicago Tribune printed rosters for the first game, but the game’s box score showed additional names that had not been noted by the Tribune; additionally, some of the players listed by the paper did not play and may not have appeared at the game at all.6

A composite list of players either earmarked by the Tribune article to play in the first game or whose names appeared in the box scores of either game follows. Seventeen players were listed in the box scores of both games.

Negro American League Players

Pitchers

- Chet Brewer, Cleveland Buckeyes (game 1)

- Vibert Ernesto Clarke, Cleveland Buckeyes (game 2)

- James “Fireball” Cohen, Indianapolis Clowns (game 2)

- Gentry “Jeep” Jessup, Chicago American Giants (game 1)

- James Lamarque, Kansas City Monarchs (both games)

- Verdel Mathis, Memphis Red Sox (game 1)

- Bill Powell, Birmingham Black Barons (game 1)

- Roberto Enrique Vargas, Chicago American Giants (game 2)

Catchers

- Lloyd “Pepper” Bassett, Birmingham Black Barons (game 2)

- Sam Hairston, Indianapolis Clowns (game 1)

- Quincy Trouppe, Chicago American Giants (both games)

Infielders

- Robert “Bob” Boyd, Memphis Red Sox (both games)

- Lorenzo “Piper” Davis, Birmingham Black Barons (both games)

- Leon Kellman, Cleveland Buckeyes (both games)

- Ray Neil, Indianapolis Clowns (listed by the Tribune, but did not appear in game 1)

- Herb Souell, Kansas City Monarchs (both games)

- Arthur Lee “Artie” Wilson, Birmingham Black Barons (both games)

Outfielders

- Willard “Homerun” Brown, Kansas City Monarchs (both games)

- Jose Colas, Memphis Red Sox (Listed in the Tribune for game 1, but did not play; played in game 2)

- Willie “Fireman” Grace, Cleveland Buckeyes (Listed in the Tribune for game 1, but did not play; played in game 2)

- Samuel “Sam” Hill, Chicago American Giants (both games)

- Cornelius “Neal” or “Shadow” Robinson, Memphis Red Sox (played in game 1, but was not listed by the Tribune)

Extra Players

- Ernest “Spoon” Carter, Memphis Red Sox (pinch-runner) (game 2)

- Sam Hairston, Indianapolis Clowns (pinch-hitter) (game 2)

(The Indianapolis Clowns identified “King Tut” as their third participant. King Tut was the Clowns’ “comedian.”)

Manager: Quincy Trouppe, Chicago American Giants

Negro National League Players

Pitchers

- Dave “Impo” Barnhill, New York Cubans (game 2)

- Joe Black, Baltimore Elite Giants (game 2)

- Wilmer Fields, Washington Homestead Grays (played in game 1, but was not listed by the Tribune)

- Robert “Schoolboy” Griffith, New York Black Yankees (game 1)

- Rufus “Mississippi” Lewis, Newark Eagles (game 1)

- Max Manning, Newark Eagles (game 2)

- Henry Miller, Philadelphia Stars (game 1)

- Robert Romby, Baltimore Elite Giants (game 1)

- Patricio Scantlebury, New York Cubans (Listed by the Tribune, but did not appear in game 1)

Catchers

- William “Ready” Cash, Philadelphia Stars (both games)

- Louis Oliver “Tommy” Louden, New York Cubans (both games)

Infielders

- Frank “Pee Wee” Austin, Philadelphia Stars (both games)

- Thomas “Pee Wee” Butts, Baltimore Elite Giants (game 1)

- George “Big George” Crowe, New York Black Yankees (game 2)

- James “Junior” Gilliam, Baltimore Elite Giants (both games)

- Buck Leonard, Washington Homestead Grays (game 1)

- Orestes “Minnie” Minoso, New York Cubans (both games)

Outfielders

- Lucius “Luke” Easter, Washington Homestead Grays (both games)

- Robert “Bob” Harvey, Newark Eagles (game 1)

- Monte Irvin, Newark Eagles (game 1)

- Lester Lockett, Baltimore Elite Giants (both games)

- Luis Marquez, Washington Homestead Grays (both games)

- James “Seabiscuit” Wilkes, Newark Eagles (game 2)

Extra Players

- Marvin “Hank” Barker, New York Black Yankees (pinch-hitter in game 2)

Manager: Jose Fernandez, New York Black Yankees; Coaches, Vic Harris, Washington Homestead Grays, and Marvin Barker, New York Black Yankees

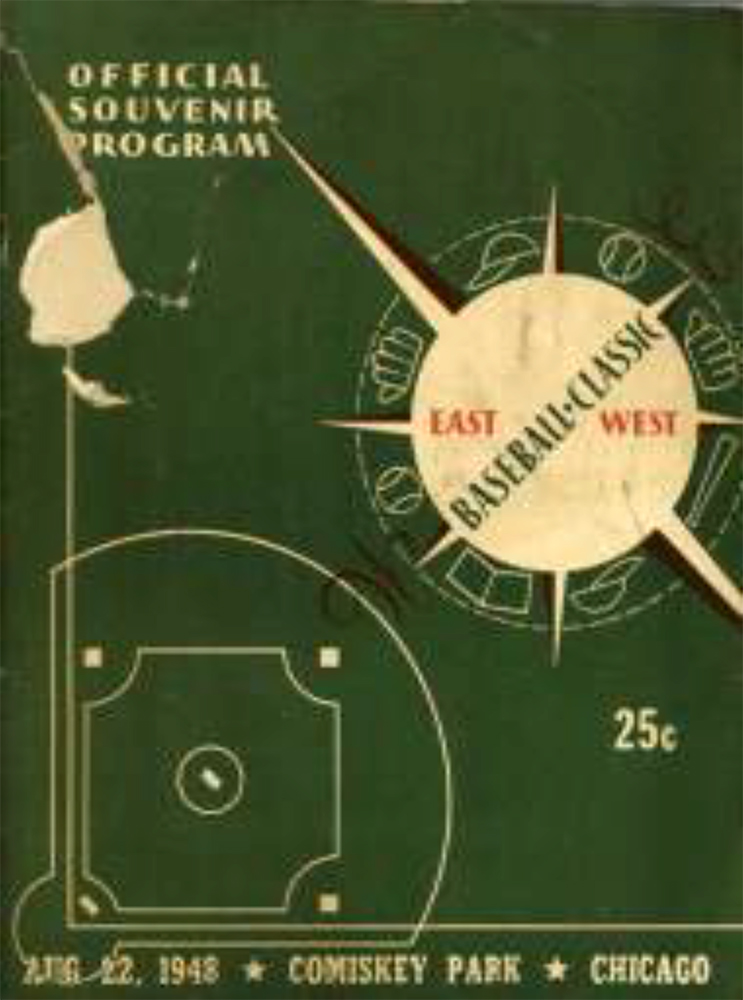

Game One: Sunday, August 22, 1948, at Comiskey Park, Chicago

Led by the pitching trio of Bill Powell of the Birmingham Black Barons, James LaMarque of the Kansas City Monarchs, and Gentry Jessup of the Chicago American Giants, the West defeated the East in a 3-0 shutout. It was the first time the East had been shut out since the inception of the All-Star Game in 1933. Each of the three West All-Star pitchers hurled three innings, holding the East to a total of three hits, one of which was a double by the 40-year-old Buck Leonard. None of the East’s baserunners managed to make it as far as third base. Powell’s three shutout innings to start the game gave him the win.

Rufus Lewis started the game well for the East by striking out the side in the first inning. However, he gave up three hits and a walk in the second, allowing the West to score two runs. Willard Brown, a future Hall of Famer who had a cup of coffee in the major leagues with the St. Louis Browns in 1947, opened the frame with a single, which was followed by Bob Boyd’s base hit to left field. Neal Robinson drove in Brown with another single; Luke Easter’s throw to the plate was wild, and allowed Boyd and Robinson to move to third and second. Quincy Trouppe was intentionally walked to load the bases. Boyd then scored on a groundball to second. Lewis’s poor inning and a lack of run scoring by the East tagged him with the loss.

The damage in the second inning could have been worse, but, as Bill Nunn of the Pittsburgh Courier recounted:

“[A]n unusual double play allowed Lewis to escape further damage in this inning. Bill Powell hit a ground ball to James Gilliam on second. Gilliam’s throw to the plate was in time to trap Robinson between third and home; He was out when William Cash, the East’s catcher, threw to Orestes Minoso at third and the latter made the putout. Minoso then turned and touched Trouppe who was caught off second.”7

The West’s third and final run came in the eighth inning against Robert Griffith of the New York Black Yankees. The Indianapolis Star reported, “Piper Davis, West second baseman from Birmingham, opened with a double. Brown singled as Davis stopped at third before scoring on Boyd’s fly.”8

The East’s only hits were Junior Gilliam’s second-inning single off Powell (Gilliam was thrown out trying to steal second), Leonard’s double in the fourth (deflecting off first baseman Boyd’s glove), and Minoso’s infield single in the sixth. Both of the latter hits were off James LaMarque, the Monarchs’ pitcher.

The Courier’s Nunn wrote, “[F]rom where we sat in the press box row, it appeared to be a very dull game, as the East was able to get only one man as far as second.” Nunn may have reconsidered as he watched the ninth inning, noting that “Robinson raced back 365 feet into left center field … and literally climbed the concrete wall as he robbed Minoso of a sure-fire triple.”9 After that gem, Lester Lockett walked, then the game ended when Buck Leonard grounded into a 4-6-3 double play.10

Game Two: Tuesday, August 24, 1948, at Yankee Stadium, New York

The East-West All-Star Game had its roots in Chicago and Comiskey Park, starting in 1933, and a total of 28 All-Star Games, including the first of two in 1948, had been played there. The game was held at Yankee Stadium twice, first as the second of a two-game series in 1939 and again for the second game in 1948. It was called the Dream Game when it was played in the East. According to the New York Amsterdam News, “Alex Pompez, a New York sportsman and owner of the New York Cubans, is chairman of the [Dream Team] committee because he did such a magnificent job last year [at the Polo Grounds] in handling the affair in such a grand manner.”11 Such accolades were afforded to Pompez because the 1947 Dream Game drew 38,402, the best attendance recorded for any East-West game outside of Comiskey Park.

The West scored first in Game Two just as it had in the first game at Comiskey Park. Sam Hill of the Chicago American Giants walked in the top of the third and stole second. Hill took third on a grounder by Vibert Clarke and scored on a single by Artie Wilson of the Birmingham Black Barons.

Held scoreless in Chicago two days earlier, the East squad got on the board in a big way at Yankee Stadium by scoring three runs in the bottom of the third off Vibert Clarke, the eventual losing pitcher.

Frank Austin of the Philadelphia Stars singled and then came home on the first and only home run of the two 1948 All-Star Games. According to the New York Times, Luis Marquez, center fielder of the Homestead Grays, tagged a 330-foot shot into the lower right-field stands to establish a 2-0 East lead. Minnie Minoso of the New York Cubans followed with a double and scored on a single to left field by Lester Lockett of the Baltimore Elite Giants.

The West was to score no more, but as the Chicago Defender reported:

“[T]he East added one more in the fourth. George Crowe, New York Black Yankees, singled off Jim Cohen of the Indianapolis Clowns. Herb Souell, Kansas City Monarchs, bobbled Frank Austin’s grounder and Crowe went to second. Cash singled Crowe to third and Dave “Impo” Barnhill, New York Cuban hurler who wasn’t even with the East nine in the Chicago game, was an infield out, Crowe scoring.”12

Crowe and Junior Gilliam figured in the final runs scored — two East tallies in the bottom of the eighth — when they both singled and later scored on an error by Cleveland Buckeyes third baseman Leon Kellmann.

The West used four pitchers in the contest, with Clarke throwing three innings and giving up three runs (all earned) to take the loss. He was followed by Jim Cohen of the Clowns (two innings pitched and one run surrendered), Roberto Vargas of the Chicago American Giants (one inning pitched, no runs allowed), and Jim LaMarque of the Monarchs (two innings pitched, two unearned runs given up).

The East threw Max Manning of the Newark Eagles, Dave Barnhill of the New York Cubans, and Joe Black of the Baltimore Elite Giants. Each pitcher tossed three innings, with Manning getting the win.13

Before the game the New York Amsterdam News had written that the game was expected to draw a crowd of about 40,000.14 As it turned out, fewer than 18,000 attended, the lowest All-Star Game attendance outside of two games that had been played in Cleveland and Washington.15

All-Star Players: The Negro League World Series, the Major Leagues, and the Hall of Fame

Players from the Homestead Grays and Birmingham Black Barons, the two teams that ended up in the 1948 Negro League World Series, did not figure all that prominently in either game. The exceptions were two Birmingham players: Game One’s winning pitcher, Bill Powell, and Artie Wilson, who went 3-for-4 in the West’s Game Two loss. Players from the two eventual World Series teams collected six of the 25 hits in the two games.

Of the 48 players identified either by the Chicago Tribune or ultimately appearing in the box score for one or both of the All-Star Games, 15 eventually played in the major leagues. All of them appeared in Game Two; this was the largest single number of Negro Leaguers who became future (or past, when including Willard Brown, who played for the Browns in 1947) major leaguers to play together in a single East-West All-Star Game.16

The 15 players and the major-league teams for which they played are:

- Willard Brown, St. Louis Browns, debuted July 19, 1947 (cut by the Browns and returned to the Kansas City Monarchs after 21 games)

- Minnie Minoso, Cleveland Indians, April 19, 1949

- Monte Irvin, New York Giants, July 8, 1949

- Luke Easter, Cleveland Indians, August 11, 1949

- Luis Marquez, Boston Braves, April 18, 1951

- Artie Wilson, New York Giants, April 18, 1951

- Sam Hairston, Chicago White Sox, July 21, 1951

- Bob Boyd, Chicago White Sox, September 8, 1951

- George Crowe, Boston Braves, April 16, 1952

- Quincy Trouppe, Cleveland Indians, April 30, 1952

- Joe Black, Brooklyn Dodgers, May 1, 1952

- Junior Gilliam, Brooklyn Dodgers, April 14, 1953

- Roberto Vargas, Milwaukee Braves, April 17, 1955

- Vibert Clarke, Washington Senators, September 4, 1955

- Pat Scantlebury, Cincinnati Redlegs, April 19, 1956

Three players in the two games were inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame: Buck Leonard, Monte Irvin, and Willard Brown.

Conclusion: The Beginning of the End for Negro League Baseball

Though Larry Lester has identified the heyday of the East-West All-Star Games as spanning from their inception in 1933 to the early 1950s, several compelling storylines emerged during and immediately after the 1948 games that affirmed the lesser role the Negro Leagues played relative to major-league baseball and indicated the writing was on the wall for the All-Star Games and the Negro leagues as a whole.

The ticket from the August 24 game made it clear which league had superiority in the pecking order between the Negro and major leagues. On it was written:

“The Colored All-Star Game Dream Game is scheduled to be played on the Night of August 24th. In the event of RAIN it will be played on the Night of August 25th. In the event the Yankee-Chicago game scheduled for the Night of August 23rd is rained out, the game will be played on August 24th, thereby postponing the All-Star Game to the Night of August 25th.”17

Although not surprising, the casual notation reminds all of the stark inequality of an earlier era, or at least who controlled the pocketbook.

The August 28 edition of the Chicago Defender noted:

“Baseball fans and the general public are blaming the slump in the East versus West game attendance to politics and ticket scalping. Last year 48,112 watched the classic. Sunday 42,099 was the attendance although it was reported a few minutes before as 37,099. Leroy “Satchel” Paige drew 51,000 in the same park on Friday night August 13th. On that night fully 15,000 were unable to get inside the park. Sunday, at the East vs. West game there weren’t 15,000 on the outside.”

The article went on to assert that the Republican Party took over the pregame ceremonies and kept away droves of Democratic supporters. Exorbitant ticket prices and ticket scalping also drove away cost-conscious fans.18 As a result, the game’s showcase lost its luster.

The Defender’s Satchel Paige reference spoke to a larger issue facing the Negro Leagues: the beginning of the exodus of its better players to Organized Baseball. In fact, Paige had pitched on Friday, August 20, in Cleveland before 78,383 fans. The Indianapolis Star wrote, “Ageless Satchel Paige shut out the Chicago White Sox with three hits last night. … The fabulous Negro hurler now has won all three of his major league starts and has a season record of five victories and only one loss. A total of 201,829 customers have jammed their way into the stands to watch Paige in his three major league starts.”19

On September 4, the Defender reported:

“[T]he crowd was asked to stand in silent tribute to the late George Herman “Babe” Ruth [Ruth had died on August 16, eight days earlier]. No mention was made of the last Negro baseball men’s death — namely Josh Gibson [January 20, 1947], hero of many an East vs. West game; Candy Jim Taylor, manager of the East nine and of the Chicago American Giants [April 3, 1948]; Cum Posey, Homestead Grays and former secretary of the Negro National League [March 28, 1946]. Maybe they didn’t amount to much in the eyes of the owners and promoters of the game but baseball fans wondered why.”20

The lack of respect accorded to the Negro Leagues was only partially mitigated by the slowly increasing number of its players who were afforded an opportunity to play in the minor or major leagues. The breaking of the color barrier brought about conflicted feelings within the African-American community about Negro League baseball, its role, and its future.

In an editorial titled “Don’t Let Negro Baseball Die!” a writer for the Pittsburgh Courier wrote:

“I pride myself on being a staunch supporter of Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, and Roy Campanella. I’m praying that Don Newcombe, Dan Bankhead, and Sammy Jethro[e] get major league calls next year, but — for God’s sake, fans, don’t let Negro baseball die! … The way I see it, Negro fans are doing Negro baseball, future Negro stars and potential major leaguers a great injustice by withdrawing their support. For if the Negro teams are forced to curtail their activities due to inability to meet expenses, the hopes of hundreds of Negro aspirants for major league careers will be doomed. How will major league scouts be able to look over Negro material if there are no Negro teams playing?”21

Though Organized Baseball’s pilfering of the best black talent resulted in the gradual demise of the Negro Leagues, there is no doubt that baseball’s integration made both the nation and its national pastime better entities.

Sources

Box scores for these games can be found at Retrosheet.org: https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/NgLgASGames.html

Notes

1 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 15, 1942: 16.

2 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/East-West_Game.

3 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 375.

4 https://baseball-reference.com/bullpen/East-West_Game.

5 “West Selects Players for Big Game Aug. 22,” Chicago Defender, July 31, 1948.

6 “Nines Picked to Compete in Negro Contest,” Chicago Tribune, August 15, 1948: 62.

7 Bill Nunn Jr., “West Wins 6th Straight over East, 3-0,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 28, 1948: 10.

8 “West Wins Negro All Star Tilt,” Indianapolis Star, August 23, 1948: 23.

9 Nunn.

10 Lester, 313.

11 “3rd Annual All Star Game at Stadium,” New York Amsterdam News, August 14, 1948, quoted in Lester, 314.

12 “Second East versus West Game Draws 17,928,” Chicago Defender, September 4, 1948, quoted in Lester, 315.

13 Ibid.

14 Swig Garlington, “40,000 Expected at Dream Game,” New York Amsterdam News, August 21, 1948, quoted in Lester, 314.

15 Lester, 321.

16 Lester, 455-456.

17 Lester, 319.

18 Morgan Holsey, “Scalpers and Politicians Mar East-West Game,” Chicago Defender, August 28, 1948.

19 “78,382 Fans See Paige Pitch Another Cleveland Shutout,” Indianapolis Star, August 21, 1948: 16.

20 “Second East versus West Game Draws 17,928.”

21 “Don’t Let Negro Baseball Die,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 4, 1948: 10.

Additional Stats

West All-Stars 3

East All-Stars 0

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

East All-Stars 6

West All-Stars 1

Yankee Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Game 1:

Game 2:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.