July 12, 1979: Chicago’s Disco Demolition Night results in White Sox loss and forfeit

Five days before the 1979 All-Star Game, two fifth-place teams in the American League had a twi-night doubleheader scheduled, as the Detroit Tigers visited the Chicago White Sox. Mike Veeck, son of White Sox owner Bill Veeck, was the director of promotions for the White Sox. He had conspired with Steve Dahl, a Chicago disc jockey, for a one-of-a-kind promotion, in order to attract crowds and improve the abysmal White Sox attendance. Chicago was riding a four-game win streak and had won seven of eight, but the team was still drawing small home crowds. The Tigers, meanwhile, had lost four of their last five games.

Dahl had been fired by Chicago radio station WDAI-FM on Christmas Eve 19781 when the station transitioned to an all-disco format; popular movies like Saturday Night Fever, released in 1977, vaulted disco music to rule the airwaves. Dahl was hired by rock station WLUP-FM and began a crusade against disco music. The popular morning radio personality was going to literally use fireworks to blow up hundreds of disco records between the two games of the doubleheader.

An electric crowd of 47,795 fans, more than 3,000 over Comiskey Park’s capacity of 44,492, packed the ballpark, eager to see the show.2 Veeck and the WLUP staff were hoping for 20,000 attendees, and security had been hired for 35,000, but some estimates put the crowd as high as 60,000.3 The stands were filled with fans who each could gain entry to the ballpark for just 98 cents (the radio frequency of WLUP, known as 98 Rock, was 97.9), “if they brought a record to be destroyed.”4 Those in attendance and in the dugouts watched as the playing field was ultimately destroyed.

The first game was set to begin at 6:00 P.M. The first pitch was thrown out by Lorelei, a “blonde rock ’n’ roll siren”5 who worked for WLUP’s advertising group. Chicago manager Don Kessinger sent Fred Howard (1-3) to the mound, opposed by Detroit’s Pat Underwood (3-0).

The Tigers scored a run in the opening frame. With one out, Lou Whitaker walked and moved to third when Rusty Staub singled into right field. With Jason Thompson batting, Staub attempted to steal second base. Chicago backstop Mike Colbern threw the ball away and Whitaker scampered home. Detroit added a run in the second. Jerry Morales reached on an error charged to third baseman Jim Morrison. He then stole second and scored as Tom Brookens drove a one-out triple into left field. The first two innings resulted in two unearned runs for the Tigers.

In the home half of the second, Rusty Torres singled to left field after Wayne Nordhagen had grounded out. Morrison struck out, but Greg Pryor lined a run-producing double to left, cutting the Detroit lead to 2-1. Chicago’s Howard continued to labor in the third. Staub drew a one-out walk and two batters later, Champ Summers singled to the right side to send Staub to second base. Morales followed with a single into right field, plating Staub. The Tigers had sent 16 batters to the plate in the first three innings. Howard settled down a bit, retiring the Tigers in order in the fourth and fifth. Meanwhile, after allowing the run in the second inning, Underwood retired 12 in a row until the bottom of the sixth, when he gave up a single to Chet Lemon and a walk to Lamar Johnson, but both runners were stranded. Underwood continued his dominance of the Chicago hitters, pitching 7⅔ innings. He allowed one earned run on five hits and two walks, and he struck out three.

Summers led off the top of the sixth with a single off Howard. He stole second, the third swipe off the Howard/Colbern battery. Morales grounded out and Summers remained at second. Lance Parrish stroked an RBI single to center, and the Tigers had a 4-1 advantage. Parrish’s base knock brought Kessinger to the mound, and Howard was done for the day. Journeyman Ed Farmer came on in relief. Chicago was the right-hander’s seventh team in seven years in the big leagues.6 Farmer finished the game for the White Sox, shutting out the Tigers on three hits.

Chicago had a mini-rally in the bottom of the eighth, with two men on and two outs, on a double from Junior Moore and a walk to Lemon. Aurelio Lopez trotted in from the bullpen and induced Johnson to hit into a force out. Lopez pitched a perfect ninth, getting Jorge Orta to foul out and then striking out pinch-hitter Claudell Washington and Morrison to end the game. Detroit won, 4-1.

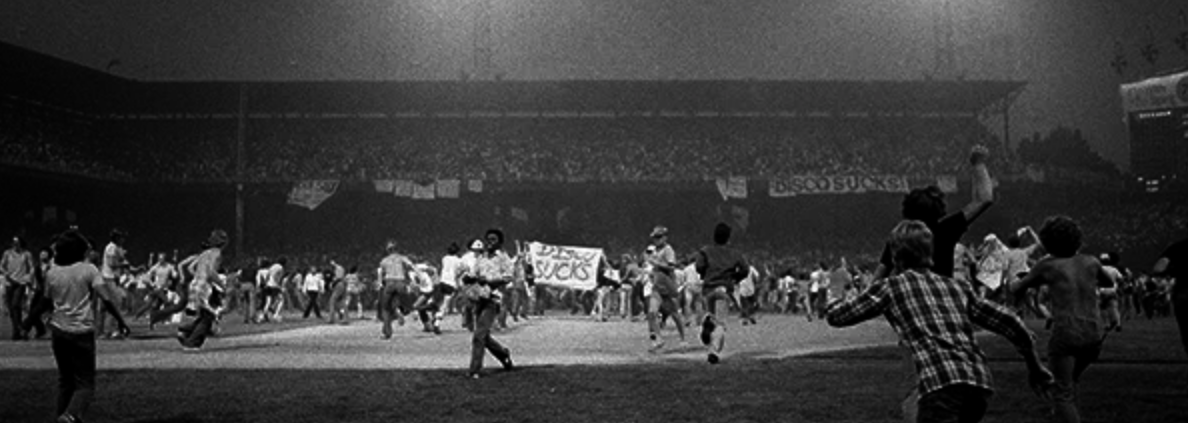

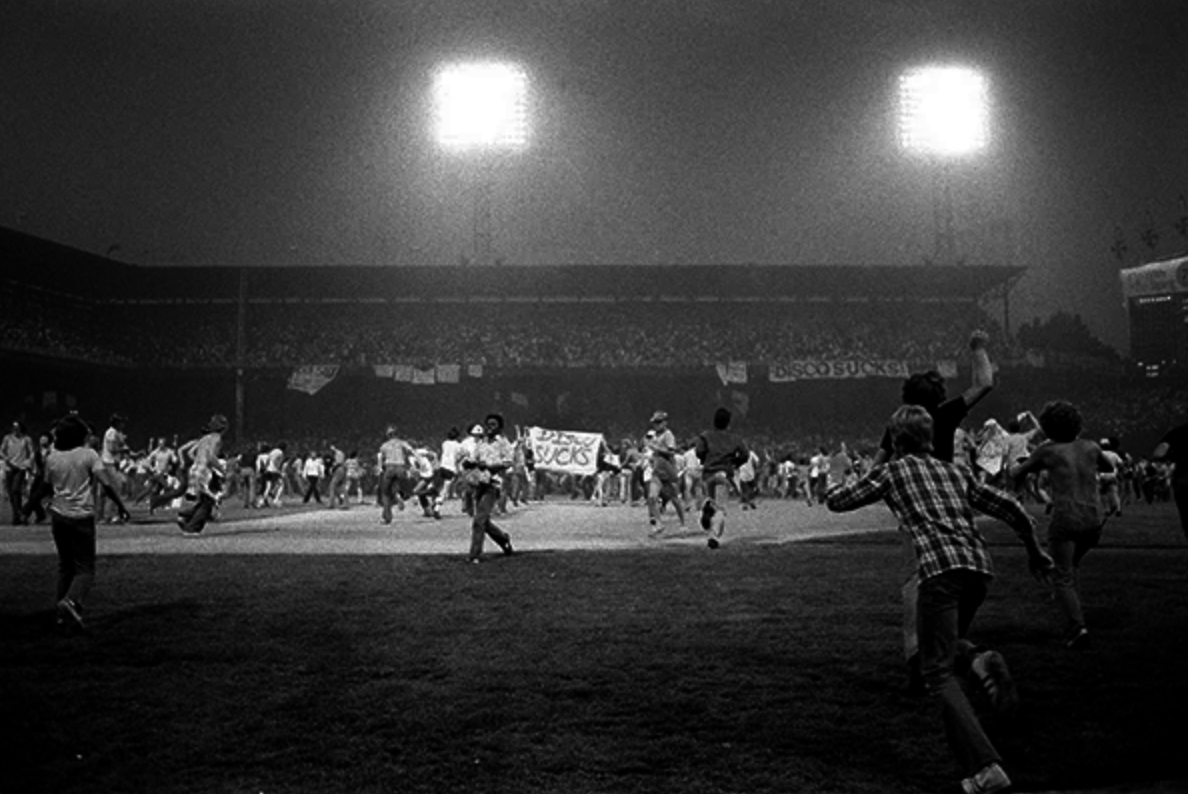

Then the show began. Dahl blew up a crate of records in the outfield and a riot ensued. According to NPR, “[A]n estimated 7,000 people slid down the foul poles, lit things on fire and literally stole the bases.”7 With the security forces outside the stadium, attempting to keep thousands of people from crashing the gates, spectators already in Comiskey Park stormed the field with little resistance. When Dahl set off the explosives, Detroit pitcher Jack Morris said, “[A]ll hell broke loose. They charged the field and started tearing up the pitching rubber and the dirt. They took the bases. They started digging out home plate.”8 White Sox announcer Harry Caray took to the public-address system, urging fans to calm down, to no avail. The batting cage was knocked over. Fans who had brought records but not turned them in started “flinging records like Frisbees.”9 Chicago police arrived and arrested 37 people.

Former AL umpire Nestor Chylak, now a supervisor of umpires, was present at Comiskey. After the riot on the field, Chylak met with the umpire crew (headed by crew chief Dave Phillips), Bill Veeck, and Tigers manager Sparky Anderson. Detroit television commentator Al Kaline (elected into the Hall of Fame in 1980) was also in attendance at the meeting. According to Kaline, the participants at the meeting were “afraid of somebody getting hurt, and also, the fact that home plate was uprooted from the ground and it has not been measured, it has not been properly put back in.”10 The only option for the White Sox was to forfeit the second game of the doubleheader. Phillips called American League President Lee MacPhail, who ordered the second game postponed until Sunday. Anderson was not satisfied and cited the rule book, insisting that the White Sox were responsible for the field conditions, which did not merit a postponement but a forfeit instead. The next day, MacPhail informed his longtime friend Bill Veeck “that his struggling White Sox had lost a game by forfeit.”11

Chicago pitcher Rich Wortham, a Texan who preferred the sounds of country crooners Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings over disco, told the Chicago Tribune that “this wouldn’t have happened if they had country and western night.”12 Thirty years after the event, the New York Times reported, “Few sports promotions ever went so awry; few are remembered as well.”13 Roland Hemond was the general manager of the White Sox and he claimed that it was a “great promotion.”14 Many folks blamed either Dahl or Mike Veeck for the riot. Sportscaster Howard Cosell instead blamed Caray, saying that Caray “contributed to a ‘carnival’ atmosphere.”15 The younger Veeck had been on the field when Dahl started his pyrotechnics. He reflected on the event almost 40 years later, saying, “I never left second base. … I was just standing there thinking about what my next job would be, because I knew that my life as I knew it right then was over.”16

There was a precedent for the forfeit, though. On April 26, 1925, the Cleveland Indians defeated the White Sox 7-2 in a not-quite-nine-inning game at Comiskey Park that was called with two outs in the ninth, after the crowd thought the game was over. It was shortened “because, the history books say, ‘the fans stormed the field.’”17

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org.

Photo courtesy of Sports Illustrated.

Notes

1 Andy Behrens, “Disco Demolition: Bell-bottoms be gone!” espn.com, July 12, 2009, found online at https://espn.com/chicago/columns/story?page=disco/090712. Accessed September 2017.

2 Sporting News Baseball Guide (St. Louis: The Sporting News Company, 1979), 11.

3 Joe LaPointe, “The Night Disco Went Up in Smoke,” New York Times, July 4, 2009, found online at https://nytimes.com/2009/07/05/sports/baseball/05disco.html. Accessed September 2017. The Chicago Tribune reported that the attendance was closer to 59,000, still more than 10,000 higher than the “official” mark of 47,795.

4 Ibid.

5 George Bova, “Disco Demolition’s Lorelei,” found online at https://whitesoxinteractive.com/rwas/index.php?category=11&id=2300. Accessed September 2017.

6 Farmer was traded to the Yankees in March 1974 but was sent to Philadelphia a week later, so he could claim eight teams from 1971 to 1979. He did not pitch in the majors in either 1975 or 1976, and pitched in only four games in 1977 and 1978.

7 John Derek, “July 12, 1979: ‘The Night Disco Died’ – Or Didn’t,” National Public Radio, July 16, 2016, found online at https://npr.org/2016.07.16/485873750/july-12-the-night-disco-died-or-didnt. Accessed September 2017.

8 LaPointe.

9 Phil Vettel, “Steve Dahl’s Disco Demolition at Comiskey Park,” Chicago Tribune, 2017, found online at https://chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/chi-chicagodays-disco-story-story.html. Accessed September 2017.

10 LaPointe.

11 Richard Dozer, “Veeck Protests Sox Forfeit, but Accepts Responsibility,” Chicago Tribune, July 14, 1979: 21.

12 David Israel, “When Fans Wanted to Rock, the Baseball Stopped,” Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1979: 62.

13 LaPointe.

14 Ibid.

15 Vettel.

16 Paul Sullivan, “’Disco Demolition’ Night Fondly, and Not-So-Fondly, Remembered,” Chicago Tribune, August 4, 2017, found online at https://chicagotribune.com/sports/columnists/ct-chicago-disco-demolition-white-sox-spt-0806-20170805-column.html. Accessed September 2017.

17 Richard Dozer, “Tigers Ask for Forfeit of 2d Game,” Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1979: 60.

Additional Stats

Detroit Tigers 4

Chicago White Sox 1

Detroit Tigers 9

Chicago White Sox 0

(forfeit)

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.