June 14, 1980: The Steve Henderson Game

Each baseball season’s early summer games take on a mystical quality in cities that endure longer, darker winters. Near June solstice, night patiently awaits dusk’s extended loitering, humidity is tolerable, and the schedule is still young enough to keep fans of even the most dismal teams buoyant for revelation. Such was the setting on a calm 70-degree Saturday evening at Shea Stadium as the hometown Mets took the field on Flag Day 1980 against the San Francisco Giants, a franchise that had abruptly abandoned the city for the West Coast a generation prior.

Each baseball season’s early summer games take on a mystical quality in cities that endure longer, darker winters. Near June solstice, night patiently awaits dusk’s extended loitering, humidity is tolerable, and the schedule is still young enough to keep fans of even the most dismal teams buoyant for revelation. Such was the setting on a calm 70-degree Saturday evening at Shea Stadium as the hometown Mets took the field on Flag Day 1980 against the San Francisco Giants, a franchise that had abruptly abandoned the city for the West Coast a generation prior.

Most of the National League followers in town had by then long since adopted the expansion Mets as an irresistibly flawed replacement since the team’s inauguration in 1962, priding themselves as anxious patrons of some of the most uncommon euphoria and agony the game had ever seen. The heroes of the franchise’s story thus far had frequently been otherwise inconsequential players who fleeted through sparse moments of glory, becoming all the more satirically etched in the forgiving memories of their fans. One more such indelible character would develop that night.

The Mets entered with a record of 26-28, in fourth place trailing the Expos by seven games in the NL East, but were playing inspired baseball of late with seven wins in their previous nine games, including a three-game sweep of the Dodgers at Shea Stadium earlier in the week, the middle game a 10-inning complete game by Craig Swan with Mike Jorgensen’s game-winning grand slam, culminated the next night by a comeback from a 5-0 deficit. The Giants were 24-33, bringing up the rear in the NL West, and had no positive momentum since consecutive series sweeps over the Cardinals and Cubs back in mid-May. The Mets offered left-hander and Brooklyn native Pete Falcone to start the game, making his 11th start of the season with a record of 3-4 and an ERA of 5.02. The Giants countered with former Rookie of the Year John “The Count” Montefusco, who grew up in nearby Long Branch, New Jersey.

Before many of the 22,918 fans found their seats, Falcone spotted the Giants four first-inning runs, three of them on second baseman Rennie Stennett’s second (and final) home run of the season. The Giants added another in the next frame, sending Falcone to an early shower. He was replaced by right-hander Mark Bomback in long relief, who walked Jack Clark to load the bases but wiggled out of further damage. Bomback issued two more free passes along with four singles over the next three innings, but San Francisco managed to convert only one more run from it all.

The score remained 6-0 Giants through the middle of the sixth, and Montefusco was no-hitting the Mets until Doug Flynn led off the bottom of the inning with a single to center. With one out, Lee Mazzilli reached on an error by Stennett and Frank Taveras bunted for a hit to suddenly load the bases for right fielder Claudell Washington, whom the Mets had acquired from the Chicago White Sox a week earlier for minor-league pitcher Jesse Anderson. Washington drove in Flynn with a fly to Larry Herndon in center, but Steve Henderson stranded the two remaining runners with his third strikeout of the night.

The score stayed 6-1 through the middle of the eighth inning and Montefusco kept the Mets to the two hits. New York gathered steam, though, when with one out Mazzilli singled to center and Taveras reached on an infield hit. Giants manager Dave Bristol stuck with his starter to face Washington, who grounded into a fielder’s choice at second base. Henderson redeemed his three prior strikeouts with an infield hit as Mazzilli streaked home to make it 6-2. Mike Jorgensen’s walk loaded the bases and finally chased Montefusco, who was replaced by reliever Greg Minton. Minton faced a dangerous predicament in catcher John Stearns, a .310 hitter on his way to a third All-Star Game appearance in four years. Minton won the encounter, fanning Stearns in what felt like the final dagger that night for the Mets.

Then came the magical ninth.

After Jeff Reardon set down the Giants in a scoreless top half of the inning, Minton went to work on a seemingly routine effort to finish off the Mets. First came an innocent groundout by Elliott Maddox, but then Flynn bunted his way on base to get the Shea blood flowing again. Jose Cardenal, who had grounded out to shortstop Johnnie LeMaster upon entering the game the previous inning as a pinch-hitter, did the same again here but advanced Flynn to second in the process. This set up Mazzilli to knock Flynn home with a single to center, inching the fans forward in their seats. Taveras then walked, reaching base for the third time and bringing Washington to bat as the potential tying run. Bristol had southpaw Gary Lavelle, his closer the season before, available for a favorable matchup versus the left-handed-hitting Washington, but chose to hang with Minton. This proved costly as Washington dropped a single to center to score Mazzilli for the second straight inning … 6-4.

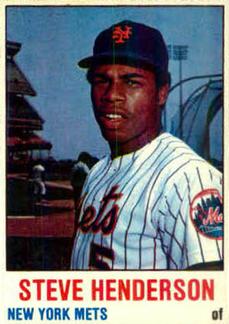

With the New York crowd now fully salivating, Bristol lifted Minton for fellow right-hander Allen Ripley, a strange move in that Ripley had become a budding starter and this would be one of only three appearances for him out of the bullpen all year. As he finished his warmups, Stephen Curtis Henderson sauntered to plate with the scoreboard bursting out in all capital letters: “HENDU CAN DO”!

It was almost three years to the day that Henderson had been acquired in an almost unthinkable trade, part of several the Mets made on a single day in what was dubbed “The Midnight Massacre.” He arrived from the Cincinnati Reds along with Doug Flynn, outfield prospect Dan Norman, and starting pitcher Pat Zachry for three-time Cy Young Award winner and future Hall of Famer Tom Seaver, who for a decade had been known simply as “The Franchise.”1 Henderson was the big bet in the deal, and Mets manager Joe Torre endorsed his enthusiasm as similar to that of Willie Mays.2 He had been a solid line-drive hitter now for several years, finished second in the 1977 Rookie of the Year voting to future Hall of Famer Andre Dawson by just two tallies, and reached base in a Mets rookie record 28 consecutive games during that campaign.

He had been something of a defensive enigma, though, and had a penchant for hitting into rally-killing double plays (he had led the league in that dubious category in ’78 with 24), something Mets fans were surely mindful of at that juncture of the game. While he hadn’t yet homered that season in 188 at-bats, he entered the day among the league batting leaders at .340. Ripley, meanwhile, had surrendered 19 long balls in 150⅓ career innings prior to this showdown. With tension palpable, Henderson laced an opposite-field line drive into the bullpen over the 371-foot marker on the right-center-field wall, unleashing the ballpark’s signature enormous plastic Big Apple from its upside-down top hat, and sending the hometown fans into an unmitigated October-esque frenzy.

The Mets, having been no-hit for five innings and down 6-1 in the eighth, had rebounded for a preposterous 7-6 victory. An appropriate exclamation point to Flag Day, to be sure. The scoreboard’s final retort: “HENDU DID DO”!

That wasn’t the only lifetime highlight in Henderson’s day. Just hours before the game that day, he became engaged, asking his future wife, Pam, to marry him. “She had just come into town and I gave her a ring at the airport — LaGuardia,” Henderson later fondly recalled during a pregame interview at Citi Field as the hitting coach of the Philadelphia Phillies. “Then I homered. That was the first homer I hit that year. I picked the right time.”3

The euphoria was short-lived. After the dramatic victory, the Mets lost their next seven games and eventually finished 67-95, and Henderson was traded a year later to the Cubs for another headliner, Dave Kingman.4 However, a week and a half prior to that sublime evening, they had drafted one of the generation’s greatest raw talents in Darryl Strawberry, who would become the initial face of the franchise’s winningest decade. That subsequent renown seemed a mountain away in 1980, but for a flash in that summer’s pan, an impossible recovery had kindled an aura of hope for the blue and orange.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and four New York Mets blogs:

Ultimate Mets.com, Independent Mets Database, ultimatemets.com/profile.php?PlayerCode=0260&tabno=7.

MetsMerizedOnline.com, Independent Mets Database, metsmerizedonline.com/2010/06/a-mets-magic-moment-turns-30.html/.

Mets360.com, Mets Blog, mets360.com/?p=31252.

AmazinAvenue.com, Mets Blog, amazinavenue.com/2013/6/3/4391810/this-date-in-mets-history-june-3-darryl-strawberry-gregg-jefferies-drafted.

Photo credit: Steve Henderson, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Associated Press, “Mets Trade Tom Seaver, Dave Kingman,” Wilmington (Delaware) Star-News, June 16, 1977: 23, news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1454&dat=19770616&id=dbosAAAAIBAJ&sjid=JRMEAAAAIBAJ&pg=5196,3178841.

2 Peter Gammons, “This Stevie Is Also a Wonder, Sports Illustrated, August 15, 1977: 42, si.com/vault/1977/08/15/643744/this-stevie-is-also-a-wonder.

3 Anthony McCarron, “Where Are They Now? Former Met Steve Henderson, Once Traded for Tom Seaver,” New York Daily News, April 22, 2015, nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/mets/steve-henderson-traded-seaver-article-1.2195267.

4 Joseph Durso, “Kingman Back With Mets; Henderson Traded to Cubs,” New York Times, March 1, 1981, nytimes.com/1981/03/01/sports/kingman-back-with-mets-henderson-traded-to-cubs.html.

Additional Stats

New York Mets 7

San Francisco Giants 6

Shea Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.