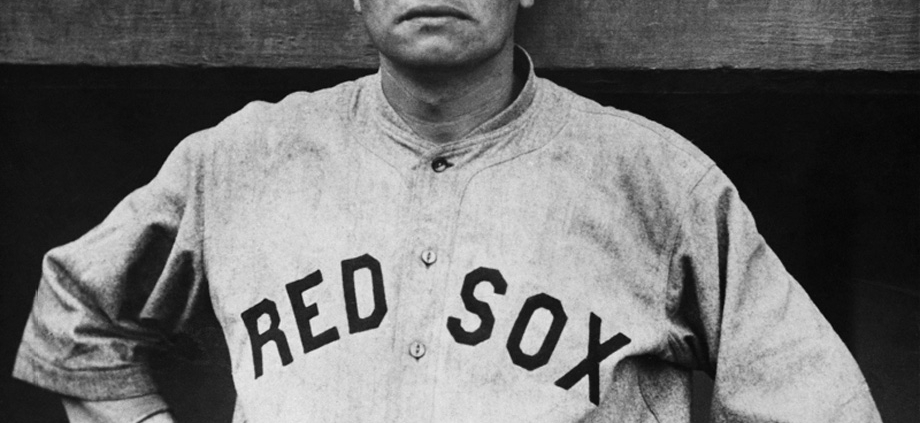

June 2, 1915: Boston’s Babe Ruth hits his first game-winning home run

In The Science of Hitting, Ted Williams wrote, “I had a higher percentage of game-winning home runs than Babe Ruth.”1 Research shows that Ted Williams had 110 game-deciding home runs, among the 521 he hit (21.11 percent). Ruth hit 126 game-winners of his own total of 714 (17.65 percent).

In The Science of Hitting, Ted Williams wrote, “I had a higher percentage of game-winning home runs than Babe Ruth.”1 Research shows that Ted Williams had 110 game-deciding home runs, among the 521 he hit (21.11 percent). Ruth hit 126 game-winners of his own total of 714 (17.65 percent).

A “game-winning home run” is defined here as a home run that provides a game’s final margin of victory, giving the winning team at least one more run than the opposing team scored. For example, if a two-run homer increased a team’s lead from 2-1 to 4-1, and they went on to win 4-3, it qualifies as a game-winning home run. (This is different from the definition of “game-winning RBI” in baseball’s official statistics from 1980 through 1988, which counted as “game-winning” the RBI that provided a winning team the lead that it never relinquished.)

Babe Ruth’s home run at the Polo Grounds on June 2, 1915, scoring the Boston Red Sox’ second and third runs in what turned out to be a 7-1 win over the New York Yankees, was his second career home run – and first-ever game-winner.2

Pitching on a cold and windy Wednesday afternoon for Bill Donovan’s Yankees was right-hander Jack Warhop (61-83 over his first seven years with New York, and 2-3 to date in 1915). After right fielder Harry Hooper flied out to lead off the first, Warhop walked second baseman Heinie Wagner and center fielder Tris Speaker. Left fielder Duffy Lewis popped up foul to third base.

Dick Hoblitzell, the first baseman, singled to left field, and the Red Sox took a 1-0 lead – despite the Yankees’ objection that Roy Hartzell’s throw from left, which nipped Speaker trying to take third, had been the third out and had occurred before Wagner had crossed home plate.

It didn’t take long for the Yankees to match that run with Ruth on the mound for Bill Carrigan’s Boston Red Sox. The 20-year-old lefty from Baltimore had been 2-1 (3.91 ERA) as a rookie in 1914. He’d won his first decision of 1915 but then lost his next four and came into this game with an ERA of 3.57.

Third baseman Fritz Maisel led off the Yankees’ first with a triple to left field and scored on Ruth’s wild pitch. Ruth rebounded to retire three of the next four batters, with only first baseman Wally Pipp reaching, on a single.

In the top of the second, the first two Red Sox grounded out. Warhop hit catcher Pinch Thomas with a pitch, bringing up Ruth, batting ninth.

Ruth drove Warhop’s pitch into the right-field grandstand for a 3-1 Red Sox lead. Warhop had also been the pitcher on May 6, when Ruth hit the first home run of his career. The two home runs landed within about 10 feet of each other.3

Ruth retired the Yankees in order in both the second and third innings.

Boston got another run in the fourth. Shortstop Everett Scott singled to center. So did third baseman Larry Gardner, Scott stopping at second. Thomas singled to shallow left and the bases were loaded. Ruth grounded to shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh, who threw home for a force out. Hooper singled to left, scoring Gardner. Wagner popped up foul to the catcher.

Right fielder Doc Cook singled in the New York fourth and stole second, but there were already two outs and Hartzell’s groundout was the third. The Boston Globe wrote, “[I]f by some strange chance a Yank got on base, Ruth tightened up and refused to permit any further liberties.”4

Neither team scored in the fifth. The only one to reach base was Hoblitzell, on a single.

The Red Sox added single runs in the sixth, eighth, and ninth. In the sixth, they drove Warhop from the game. Gardner singled to center. Thomas singled to right, but Gardner was thrown out trying to go first to third. Thomas took second on the throw. Ruth walked. After Hooper hit a single to right field, scoring Thomas with Boston’s fifth run and sending Ruth to third, Donovan had Cy Pieh come in to relieve. Ruth was tagged out at the plate when Wagner hit to Maisel at third. Speaker walked, loading the bases, but Lewis fouled out.

The only batter to reach base for the Yankees in the seventh was Cook, hit by a pitch.

Ruth walked leading off the eighth. Hooper singled to right. Wagner sacrificed to advance both baserunners. The Red Sox had their third runner thrown out at the plate – Ruth, for the second time – on a ball Speaker hit to Luke Boone at second base.

But Speaker took off on a steal of second base, with catcher Les Nunamaker’s throw going into center, allowing Hooper to scamper home. Newspaper game accounts and box scores reflect a double steal. The Red Sox’ lead was now 6-1.

In the bottom of the eighth, all four Yankees batters hit to right field. Nunamaker singled, but Pieh, Maisel, and Peckinpaugh all flied out, one after the other.

Boston bumped the score up by a run in the ninth, making it 7-1. Hoblitzell walked. Scott bunted him to second, Pieh throwing to Pipp for the out at first. Gardner singled to center field and Hobby scored. Thomas flied out and Ruth popped up to short.

With Ruth needing only three outs to close out the game, center fielder Birdie Cree walked to lead off the Yankees ninth. He was forced at second by a ball Pipp hit to Wagner. Cook singled. Hartzell struck out, and Boone flied out to center.

Ruth had improved his season record to 2-4, allowing only five hits, and no more than one in an inning after the first. His two-run homer in the second inning had broken the tie and given Boston a 3-1 lead, which held to the end of the game while the Red Sox continued to add four more runs. The homer had “put his team firmly, permanently, unalterably and irrevocably in the lead.”5

Fans were just beginning to learn about Babe Ruth. This was only his 17th game in the major leagues, and his second in New York. He had pitched in 13 previous games and pinch-hit in four others. The New York Times started its game story with an introduction: “His name is Babe Ruth. He is built like a bale of cotton and pitches left-handed for the Boston Red Sox. All left-handers are peculiar, and Babe is no exception, because he can also bat.”6

Besides Ruth’s home run, Gardner led Boston’s 14-hit attack by going 4-for-5 (all singles) and Hoblitzell had a three-hit game (also all singles).

The game had attracted only 800 patrons. The Yankees hadn’t finished among the top four teams in the league since 1910. They finished 1915 in fifth place, 32½ games behind pennant-winning Boston.

Ruth finished the 1915 season with a record of 18-8 (2.44 ERA) in his first full year in the majors. In 1916 his 1.75 ERA led the league. He was 23-12 that year. Ruth wasn’t asked to pitch in the 1915 World Series, which the Red Sox won over the Philadelphia Phillies. His only appearance was as a pinch-hitter in the ninth inning of Game One. Losing 3-1, the Red Sox had a runner on first base with one out. Batting for Ernie Shore, Ruth grounded out to first base, unassisted, for the second out of the inning. Hooper was the final batter. He popped up to first base. It was the only game the Phillies won.

After his home run on June 2, Ruth hit two more in 1915 – one was on June 25 against the Yankees during a 9-5 win and the other was on July 21 in a 4-2 win over the Browns at St. Louis. Ruth was 4-for-4 in the July 21 game with a home run and two doubles. His third-inning home run was “one of the longest ever made at Sportsman’s Park,” clearing the right-field fence, the right-field bleachers, and out onto Grand Avenue beyond.7 But it was a solo home run, scoring the first run of the game. It was his RBI double in the top of the seventh that gave the Red Sox their third run in the 4-2 game.

Ruth hit the four home runs in 1915, then three in 1916, and two in 1917. After his first four years in the majors, he had a total of nine home runs. Ruth broke out in 1918 – the first season that the Red Sox used him as a position player when he was not pitching, giving him nearly as many plate appearances in 1918 as he had in his first four seasons combined – to lead both leagues with 11 homers.8

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Gary Belleville and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA191506020.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1915/B06020NYA1915.htm

Notes

1 Ted Williams and John Underwood, The Science of Hitting, 25. His methodology to come up with the statement was not spelled out. The question is explored in depth in Bill Nowlin, “The Kid” Blasts a Winner: Ted Williams’s 110 Game-Deciding Home Runs (South Orange, New Jersey: Summer Game Books, 2021).

2 Ruth had previously hit a home run on May 6, but in a game the Red Sox lost. He had not hit any home runs in 1914.

3 Heywood Broun, “Yankees Find Ruth No Babe on Diamond,” New York Tribune, June 3, 1915: 12.

4 “Red Sox, Ruth Pitching, Beat Yankees, 7-1,” Boston Globe, June 3, 1915: 6.

5 William B. Hanna, “Ruth’s Bat Builds Lead, and His Arm Defends It,” New York Sun, June 3, 1915: 8.

6 “Left-Hander Ruth Puzzles Yankees,” New York Times, June 3, 1915: 9. The article continued with a lengthy discourse on Ruth: “The big pitcher’s architectural make-up is of such a nature that it doesn’t lend itself to speed. He rather rolls along. No one knows this better than Ruth and that is why, when he hits the ball, he makes home runs. The fact is, that is the only way he can score a run. If he hit a single, the only way he could get around the bases would be in an automobile or on a motorcycle, so he chose the alternative of poling the ball out of the lot and walking leisurely over the excursion route. His clout was the longest of the season and it propelled Thomas home ahead of him.”

7 Sid C. Keener, “Red Sox Defeat Browns and Gain,” Boston Journal, July 22, 1915: 9. The Boston Herald said the ball “landed miles and miles away in the midst of a throbbing brewery district.” See “Ruth’s Hitting Big Feature of Sox Win,” Boston Herald, July 22, 1915: 4.

8 Ruth’s former teammate Tillie Walker, with the Athletics in 1918, shared the league lead with 11 home runs of his own. Ruth had 407 plate appearances combined from 1914 through 1917, and 382 plate appearances in 1918.

Additional Stats

Boston Red Sox 7

New York Yankees 1

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.