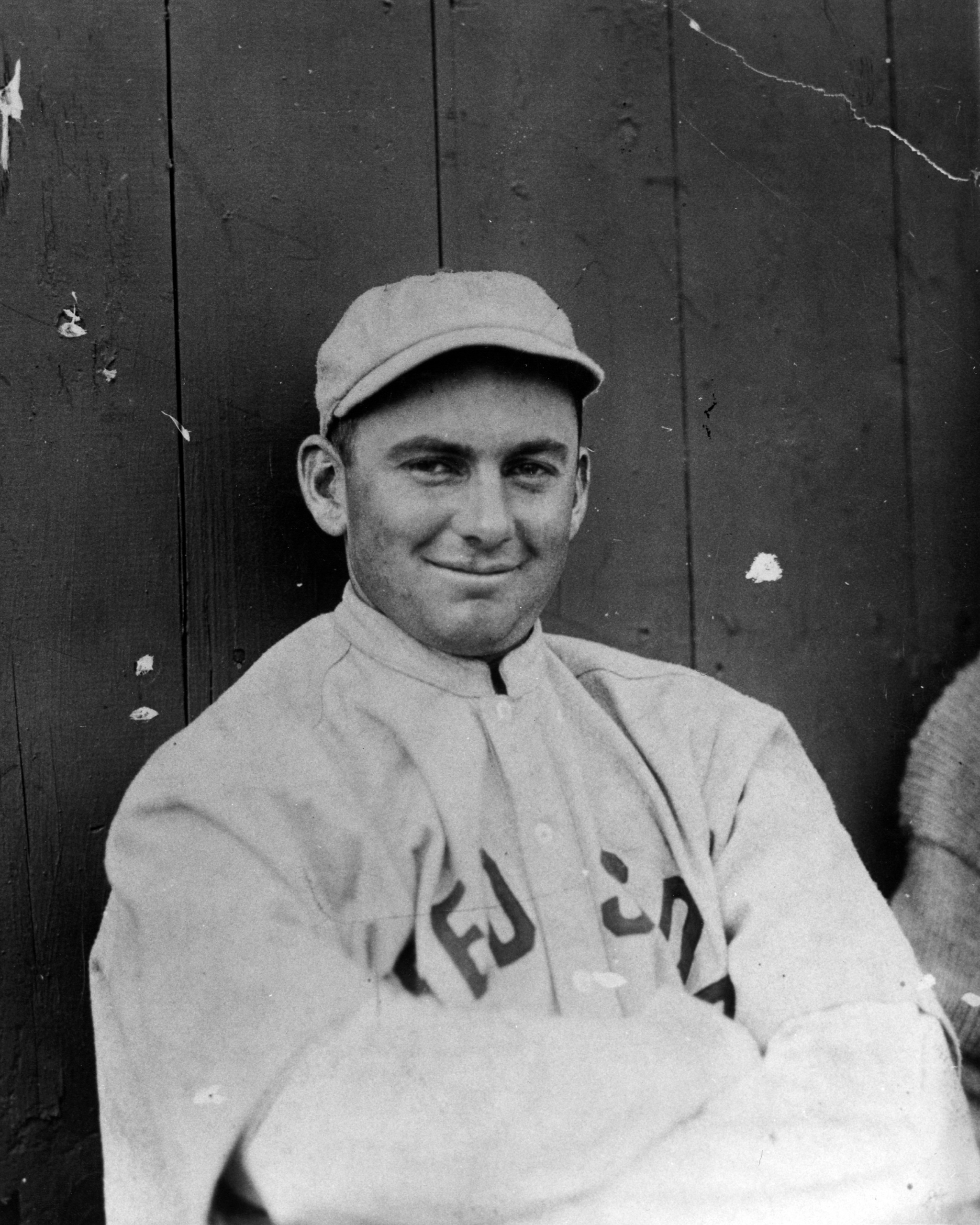

Duffy Lewis

For decades after they last played together, the Boston Red Sox’ outfield of Duffy Lewis, Tris Speaker, and Harry Hooper, who toiled next to each other for six years in the Deadball Era, was often considered the greatest in baseball history. Although all three, especially Speaker, were fine hitters, their reputation was due largely to their exceptional defensive play. Lewis, the left fielder and the only one of the three not in baseball’s Hall of Fame, was long remembered for the way he played the incline at the base of Fenway Park’s left-field wall, a slope of grass that bore the name “Duffy’s Cliff.” Hooper thought Lewis was the best of the three “at making the backhand running catch at balls hit over his head.” A powerful left-handed batter, the 5-foot-10, 170-pound Lewis typically batted behind Speaker in the cleanup position, and often ranked among American League leaders in home runs and runs batted in.

For decades after they last played together, the Boston Red Sox’ outfield of Duffy Lewis, Tris Speaker, and Harry Hooper, who toiled next to each other for six years in the Deadball Era, was often considered the greatest in baseball history. Although all three, especially Speaker, were fine hitters, their reputation was due largely to their exceptional defensive play. Lewis, the left fielder and the only one of the three not in baseball’s Hall of Fame, was long remembered for the way he played the incline at the base of Fenway Park’s left-field wall, a slope of grass that bore the name “Duffy’s Cliff.” Hooper thought Lewis was the best of the three “at making the backhand running catch at balls hit over his head.” A powerful left-handed batter, the 5-foot-10, 170-pound Lewis typically batted behind Speaker in the cleanup position, and often ranked among American League leaders in home runs and runs batted in.

George Edward Lewis was born on April 18, 1888, in San Francisco to George and Mary Lewis. He was the youngest of three children, following Agnes by four years and Edward by two. Young George acquired his lifelong nickname, Duffy, from his mother’s maiden name. On April 18, 1906 – Duffy’s 18th birthday – the infamous earthquake and fire ravaged his hometown. “I thought the whole world was coming to an end,” he later said. Lewis attended and played baseball at St. Mary’s College for one year, before signing with the Alameda team in the California League in 1907. In mid-1908 he joined the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League, and he continued his apprenticeship the next year, playing in 200 games and batting .279 in 1909. John I. Taylor, the Red Sox owner, first discovered Lewis playing for Yuma, Arizona, in the Imperial Valley League during the winter of 1908-09, and in September 1909 drafted his contract from the Oaks. After the 1909 season, Taylor went west and signed Lewis himself.

Lewis joined the Red Sox in spring training at Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1910. He apparently did not take too kindly to the treatment accorded to rookies, refusing, for example, to limit his time in the batting cage or to back down from confrontations with his fellow players. Tris Speaker, in particular, did not take to Lewis’s outspoken and cocky demeanor, leading to a prickly relationship that lasted throughout their many years as teammates. Lewis also irritated the team’s new manager, Patsy Donovan, who fined and then benched the brash rookie. Duffy played in 151 games his rookie season, hitting .283 with eight home runs, only two fewer than the league-leading figure, and 29 doubles, which placed him third in the league. In 1911 Lewis’s average climbed to .307, a career high, and his seven home runs tied for fourth in the circuit. After the season Lewis was to be wed to Eleanor Keane, a young baseball fan he had met at the Huntington Avenue Grounds. But at the urging of Red Sox owner Taylor, Lewis broke off the engagement two days before the wedding and headed back to California. Keane was the third woman with whom Lewis had broken off an engagement, but a month later the couple reconciled and were married in San Rafael, California.

When Boston’s Fenway Park was built in 1912, the ten-foot embankment in deep left field was one of its most interesting trademarks. Lewis covered this ground for six years, and became its master. “I’d go out to the ballpark mornings,” he told a sportswriter, “and have somebody hit the ball again and again out to the wall. I experimented with every angle of approach up the cliff until I learned to play the slope correctly. Sometimes it would be tougher coming back down the slope than going up. With runners on base, you had to come off the cliff throwing.” The slope remained until 1933, when Fenway Park was thoroughly renovated.

In 1912 Lewis’s .284 batting average was solid, but it was his 109 RBIs, tied for second in the league, that contributed the most to his first championship team. In the famous duel between Walter Johnson and Smoky Joe Wood on September 6, Lewis’s bloop double down the right-field line against the Big Train plated the only run of the contest. Although the Red Sox won a classic World Series over the Giants that fall, Lewis hit just .188 and made a costly error in the second game.

Lewis’s frosty relationship with Speaker continued. During the summer of 1913 things deteriorated when Speaker continually knocked Lewis’s cap off his head, revealing Duffy’s heavily receding hairline. Finally, when Speaker persisted one time too many, Lewis threw his bat at his teammate, hitting him in the shins hard enough that Speaker had to be helped from the field. This friction did not affect their play on the field, as they helped form what may have been the best defensive outfield in baseball history. In 1913 the three accounted for an astonishing 84 assists, including 29 by Lewis.

Lewis hit .298 with 90 RBIs in 1913 as the Red Sox dropped to fourth place, and, after resisting the advances of the Federal League to jump his team, managed just .278 the following year. A story Lewis loved telling in later years was about the time he pinch-hit for Babe Ruth. On July 11, 1914, Ruth made his major-league debut, hurling a 4-3 victory over the Cleveland Indians. Lewis hit for Ruth in the seventh inning and singled, helping to give his young teammate the victory.

Lewis hit .291 in 1915, and made up for his subpar 1912 Series performance by hitting .444 in the 1915 fall classic, driving in five of the twelve runs the Red Sox scored in their five-game triumph over the Philadelphia Phillies. He drove in the game-winner off Grover Cleveland Alexander in the bottom of the ninth of the third game and plated the winning run on a double in the fourth contest, while also making game-saving catches in both games. He also blasted a long drive that bounced into the center-field bleachers for a game-tying home run (legal until 1931) off Eppa Rixey in the finale. Of Lewis’s stellar defense, the Boston Globe’s Tim Murnane wrote, “The all-around work of the modest Californian never has been equaled in a big Series.” After this star-making performance, Lewis was in such demand that a San Francisco vaudeville production paid him $750 a week to perform that winter.

Speaker was traded to the Indians before the 1916 season, for two players and $55,000. Manager Bill Carrigan experimented briefly with Lewis in center field before Duffy moved back to his familiar cliff in left. Lewis slumped to .268 in 1916, but on his return to the World Series (a five-game triumph over the Brooklyn Robins) he hit .353 (6-for-17). The following season Lewis hit .302 with a team-leading 167 hits.

Lewis spent the 1918 season in the US Navy, missing out on his team’s 1918 World Series championship while serving as player-manager of a naval baseball team at Mare Island, California, near his hometown. Discharged from the service, in December 1918 he was traded to the Yankees, along with Dutch Leonard and Ernie Shore, for $15,000 plus Frank Gilhooley, Al Walters, Slim Love, and Ray Caldwell, none of whom would make significant contributions to the Red Sox. After being dealt, Lewis initially considered quitting unless he was given a larger contract. Once he reported, he hit .272 with seven home runs (more than his previous five seasons combined, thanks to the Polo Grounds’ short porch) and a team-high 89 RBIs. In 1920 he found himself fighting for playing time (.271 in 107 games) after the acquisition of Babe Ruth and the debut of rookie Bob Meusel. After the season Lewis was traded to the Washington Senators, for whom he hit .186 in just 27 games before being released in mid-June.

After his release from the Senators Lewis joined Salt Lake City of the Pacific Coast League, where he played through the 1924 campaign. He hit a league-high .403 in 1921, and took over as manager the next three years, in which he hit .362, .358, and .392. In 1925, he was the player-manager of Portland in the PCL, hitting .294 for the Beavers. He finished his playing career with Mobile, Jersey City, and Portland (Maine) in 1926 and 1927, acting as manager at both Mobile and Portland.

His finances wiped out by the stock-market crash, Lewis was a coach for the Boston Braves from 1931 to 1935, and may have been the only man to have witnessed Babe Ruth’s first home run (when he was Lewis’s Red Sox teammate in 1915) and last (when Ruth was playing out the string for the 1935 Braves). In 1936 Lewis became the traveling secretary of the Braves, a post he held for 26 years, finishing in 1961 after the team had relocated to Milwaukee. His motto was “Pay another buck and travel first class,” and he became renowned around the league with bellhops and waiters as a big tipper, replete with a snap-brim fedora, diamond stickpin, and fancy vests.

In 1950 the 62-year-old Lewis played in one final professional game for the Texas League’s Dallas Eagles as part of a promotional stunt. Lewis was often called upon to return to Fenway Park, and appeared in several old-timers games. He attended a celebration of the park’s 50th anniversary in 1962 along with many of his 1912 teammates. In 1975 the 86-year-old Lewis threw out the first ball on Opening Day, in honor of the team’s 75th season, and again before the famous sixth game of that season’s World Series.

Lewis spent his later years in retirement in Salem, New Hampshire, with Eleanor. They had no children. He spent much of his time at Rockingham Park, a nearby horse track, where he had his own suite. A dapper dresser, he was said to own 72 suits. Lewis died in Salem at the age of 91 on June 17, 1979, three years after his beloved wife. At the time of his death he had no known living relatives and no money, and was buried in an unmarked grave in Holy Cross Cemetery in Londonderry, just outside of Salem. In 2001 a collection was taken up to pay for a headstone, engraving, and upkeep on the plot.

Note: This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

A primary source for this work was Duffy Lewis’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. Other sources include:

Ellery Clark, Boston Red Sox 75th Anniversary History (Hicksville, New York: Exposition Banner, 1975).

Ellery Clark. Red Sox Fever (Hicksville, New York: Exposition Banner, 1975).

Ellery Clark. Red Sox Forever (Hicksville, New York: Exposition Banner, 1977).

Frederick G. Lieb. The Boston Red Sox (New York: Putnam, 1947).

Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson. Red Sox Century (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000).

Paul J. Zingg, Harry Hooper, An American Baseball Life (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois, 1993).

Full Name

George Edward Lewis

Born

April 18, 1888 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

June 17, 1979 at Salem, NH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.