June 20, 1931: Boston Braves celebrate Fred Hoey Day

My dear Mr. Whitman,

While “days” for baseball players are in vogue, I would like to suggest some sort of a testimonial of appreciation to Fred Hoey for the splendid service he has rendered to baseball and to the thousands of fans who cannot always be at the game. I am sure that great numbers of people would welcome an opportunity to contribute to such a testimonial.

I don’t know how such a thing is started, but I offer the suggestion and I hope I may have the opportunity to contribute.

Sincerely yours,

Palmer York1

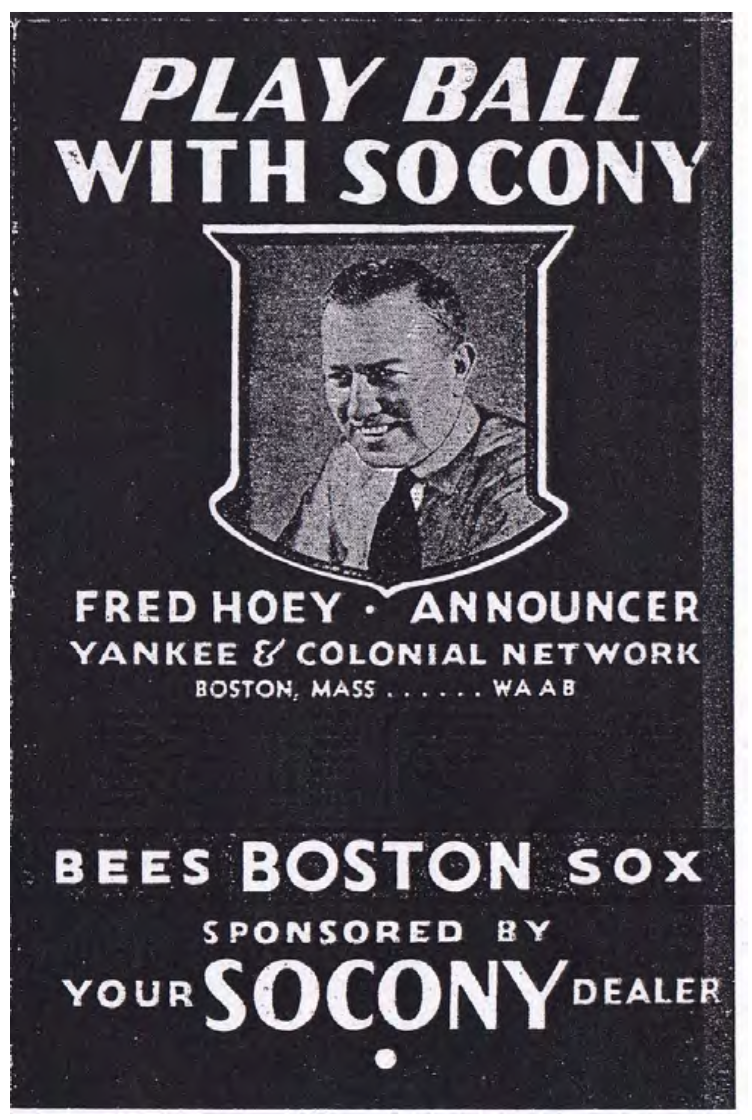

A crowd of 30,000 filed into Braves Field in Boston on a hot Saturday, June 20, 1931, as the Braves faced the St. Louis Cardinals in a doubleheader. Many of those fans were anxiously anticipating not the games themselves, but the ceremony between them. They came to show appreciation for popular Braves radio broadcaster Fred Hoey, the first regular baseball announcer in Boston.2 He had been a longtime sportswriter for several Boston newspapers, beginning with the Boston Journal in 1909, then on to the Boston Herald and Boston American. He began broadcasting Braves and Red Sox games on the radio in 1927, when radio was still in its infancy.3 Fans who could not have attended a game experienced it through the voice of Hoey, and now many came to say thanks.

A crowd of 30,000 filed into Braves Field in Boston on a hot Saturday, June 20, 1931, as the Braves faced the St. Louis Cardinals in a doubleheader. Many of those fans were anxiously anticipating not the games themselves, but the ceremony between them. They came to show appreciation for popular Braves radio broadcaster Fred Hoey, the first regular baseball announcer in Boston.2 He had been a longtime sportswriter for several Boston newspapers, beginning with the Boston Journal in 1909, then on to the Boston Herald and Boston American. He began broadcasting Braves and Red Sox games on the radio in 1927, when radio was still in its infancy.3 Fans who could not have attended a game experienced it through the voice of Hoey, and now many came to say thanks.

“If all this did not constitute a perfect day,” wrote James C. O’Leary of the Boston Globe, “it certainly ought to stand until the perfect day comes along.”4

The Braves announced that “hundreds of fans have signified their wish to help make a Hoey day a success. Stay-ins and shut-ins will have a chance to show their appreciation.”5 Fans had sent in gifts, and Harry Faunce, who worked the turnstiles at Braves Field, wrote a song for the occasion, entitled “It’s a Great Game.”6

“From all parts of New England the fans and those who seldom attend games, but often listen to them, are sending in their requests for tickets. Probably some of the outlying fans will not be able to attend, and those who will find themselves up against that obstacle are sending donations,” wrote Burt Whitman of the Boston Herald.7

Ken Coleman, a young listener to Hoey who would one day himself become a Red Sox broadcaster, said Hoey “wasn’t polished. He wasn’t a professional. … There was an electricity to him – not in how he used the language, particularly, but in the feeling he gave that this mattered, that baseball counted, that it meant something special in our lives.”8

Hoey received a bank certificate of deposit for $3,000 from the fans, money from the Red Sox and Braves, a wristwatch, gold, a pipe, and even a check from the visiting Cardinals. A box of silk shirts came from Boys of Quincy, and flowers came from relatives. Fans sent gifts of cakes, socks, and neckties. Burt Whitman concluded (considering it was Father’s Day), that “some of the fans had robbed dad of the things they were planning to give him today.”9

Speeches were made by Suffolk County District Attorney William J. Foley; the Braves owner, Judge Emil Fuchs; Boston Post sportswriter Jack Malaney; and Johnny Igoe, a druggist and local sports figure..

Being emotionally affected, Hoey “did his talking into the mike and modestly and with well-chosen words, as usual, thanked his friends. He received a tumultuous ovation when he first walked to the plate,” wrote Burt Whitman.10

The Waltham (Massachusetts) High School band “gave a splendid exhibition of marching, and the baton swinging of the girl drum major was a very interesting feature,” the Boston Globe reported. Music was also provided by Jimmy Coughlin’s 101st Regiment Veterans band.11 Being so inspired, Rabbit Maranville of the Braves was seen practicing twirling a bat in the dugout, in case he was needed to perform.

To make the day even more satisfying, the Braves won both games of the doubleheader.

Tom Zachary pitched an outstanding game one for the Braves, allowing one unearned run on only four hits and no walks. Zachary zipped through the first two innings, throwing only 10 pitches. James C. O’Leary remarked, “A fan who says he kept track of them thereafter says he never pitched more than two balls to any one batter during the game, which probably would be a record if there were any way of determining the fact absolutely.”12

Flint Rhem pitched for the Cardinals. The Braves scored a run in the third inning when Zachary doubled to right field, moved to third base on a wild pickoff throw from catcher Gus Mancuso, and scored on a wild pitch.

The Cardinals tied the score with an unearned run in the fourth inning. Frankie Frisch reached on a fielder’s choice, stole second base and reached third base as catcher Al Spohrer made a wild throw. Frisch scored on a groundout.

In the fourth inning the Braves had back-to-back singles by Red Worthington and Earl Sheely. Wes Schulmerich drove a line drive to deep center field, just over the glove of a leaping Pepper Martin. Worthington scored, giving the Braves a 2-1 lead.

In the bottom of the seventh inning, after two were out, Worthington and Sheely singled, and Frisch lost a fly by Schulmerich in the sun. It went for a double and Worthington scored. Spohrer was walked intentionally, then Freddie Maguire doubled, scoring Sheely and Schulmerich, making it 5-1 Braves.

Frisch of the Cardinals made the fielding play of the game. In the eighth inning he made a diving catch “then turned three or four somersaults before he came to a stop and came up with the ball. The big crowd applauded him all the way to the bench,” observed James C. O’Leary.13

Zachary finished the complete-game 5-1 victory for the Braves, who outhit the Cardinals 14 to 4 and left 11 runners on base.

In game two, the Braves scored in the first inning off Cardinals starter Jim Lindsey as Bill Dreesen doubled and scored on a Worthington single. The Braves added a run in the fourth inning when Schulmerich tripled and scored on Bill Cronin’s single.

The Cardinals rallied in the fifth and sixth innings. Consecutive singles by Martin, Jimmie Wilson, and Jake Flowers produced a run in the fifth inning, then Chick Hafey scored on a passed ball to tie the score, 2-2, in the sixth.

In the bottom of the ninth, with the score still 2-2, Maguire doubled off Tony Kaufmann on a ball that took a funny hop and bounded away from third baseman Sparky Adams. Maguire moved to third on a sacrifice bunt, and then scored on a walk-off single by Dreesen. Bruce Cunningham went the distance for the Braves, allowing one earned run.

“So far as the Braves and the fans are concerned, Freddy Hoey can have a day every day provided he can guarantee of two games for the Braves against tough first division competition,” concluded Burt Whitman.14

In later years, Hoey’s WNAC producer, Jack Moakley, summed up his influence by saying, “In the old days we had our ears and our imaginations and Fred made that ballpark just as big and as little, as green or as brown as he desired. We depended on Fred to tell us why the crowd was hollering and where the ball went. In that era I don’t think there was anyone better than Fred Hoey.”15

Boston fans would long remember Hoey’s voice in those early years on the radio. In this day of instant communication, it is hard for us to imagine what that voice meant to Boston fans listening to him describe the game for them. “On the air, Fred was Boston baseball,” Ken Coleman remarked.16 One fan, Bill Ahearn of Everett, Massachusetts, wrote to the Boston Herald Traveler 40 years later:

“I started following baseball in 1930, and any real baseball fan that remembers Fred Hoey will tell you that he was the best ball announcer that Boston ever had. He had the voice and every fan liked his delivery. In those days, dozens of fans walking the streets of Boston would stop at candy stands and stores that aired the game to listen to Fred Hoey. He was good, believe me.”17

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the text, the author used baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org for accounts of the games.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN193106201.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN193106202.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1931/B06201BSN1931.htm

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1931/B06202BSN1931.htm

Notes

1 Burt Whitman, “Baseball Fan Writes Urging Fred Hoey Be Given ‘Day’ for His Baseball Broadcasting,” Boston Herald, August 27, 1930, 28.

2 Fred Hoey was born in Boston (1884 is the date written on his draft cards, while other records list 1885) and raised in Saxonville, Massachusetts, a section of the town of Framingham. Hoey’s got his first experience with baseball when his father took him to Boston’s South End Grounds to see the Boston Beaneaters play Baltimore for the 1897 Temple Cup. Hoey was a semipro athlete, and became a hockey and football referee as well as a baseball umpire. He was the head usher at the Red Sox’ Huntington Avenue Grounds in Boston, then wrote for three Boston newspapers, the Journal, the Herald, and the American. Hoey covered numerous sporting events, but mostly covered school athletics, even picking his own all-scholastic teams. He later became the Braves’ official scorer. Hoey became the publicity director for the Boston Arena and was a major factor in the spread of hockey in the Boston area.

Hoey was already a well-known Boston sports celebrity when he became the first regular baseball radio announcer. He broadcast Braves and Red Sox home games for WNAC, which was owned by John Shepard. Shepard created a regional radio network, the Yankee Network, which had a listening audience of 5 million, according to Edgar G. Brands of The Sporting News (May 7, 1936).

Hoey kept a chart with details of each player in the game so as not to trust any details to memory. Boston fans campaigned for Hoey to be a World Series announcer, and got their wish in 1933, when the New York Giants played the Washington Senators. But in Game One Hoey lost his voice and had to be replaced. He had been suffering from a cold but refused to stop smoking his pipe, making his voice garbled and inaudible. Hoey always kept throat lozenges. Rumors circulated, however, that Hoey’s well-known drinking problem was to blame, and that he came to the radio booth drunk. Hoey did have another chance at a national broadcast, however, as he announced the 1936 All-Star Game from Boston. There was constant friction between Hoey and Yankee Network owner Shepard, and Shepard attempted to fire him in 1936. Public protests, including one by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, won Hoey his job back. After 1938, however, Hoey asked for a raise and was fired. This time the public couldn’t save him, and his broadcasting career ended. Hoey began a new sports show evenings on WBZ in 1939 and wrote for the Boston American into the 1940s. He died in 1949 after an accident at his home in Winthrop, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb.

3 Some accounts list Hoey as beginning his broadcasting career in 1925, the first year of radio broadcasts from Braves Field. Newspaper accounts from the era list Hoey as having a 12-year broadcasting career in Boston from 1927-1938. He is first mentioned as a broadcaster in 1927.

4 James C. O’Leary, “Braves Take Two Games From Cards,” Boston Globe, June 21, 1931, A1.

5 “Fuchs Plans Day for Fred Hoey in June,” Boston Herald, January 8, 1931, 31.

6 “Fans Turn Out to Pay Tribute to Fred Hoey at Wigwam Today,” Boston Herald, June 20, 1931, 5. You can find a copy of the score to “It’s a Grand Old Game,” with words and music by Harry Smith Faunce, at the Giamatti Research Center Library at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

7 Burt Whitman, “Fighting Braves Return Home Today to Open Six-Game Series With League-Leading Cardinals,” Boston Herald, June 18, 1931, 21.

8 Curt Smith, Voices of the Game (New York: Fireside, 1987), 24.

9 Burt Whitman, “Fred Hoey Day Proves Lucky One for Tribe,” Boston Herald, June 21, 1932, 22.

10 Ibid.

11 “Fred Hoey Day at Wigwam Great Tribute to Radio Announcer,” Boston Globe, June 21, 1931, 25.

12 O’Leary, “Braves Take Two Games From Cards,” 25.

13 Ibid.

14 Whitman, “Fred Hoey Day Proves Lucky,” 19.

15 Ted Patterson, Golden Voices of Baseball (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Pub LLC, 2002), 103.

16 Voices of the Game, 24.

17 “Mailbag – Our Readers Write on Hunters’ Day, Fred Hoey,” Boston Herald Traveler, September 20, 1972, 28.

Additional Stats

Boston Braves 5

St. Louis Cardinals 1

Boston Braves 3

St. Louis Cardinals 2

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Game 1:

Game 2:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.