June 21, 1888: George Van Haltren tosses rain-shortened no-hitter for Chicago

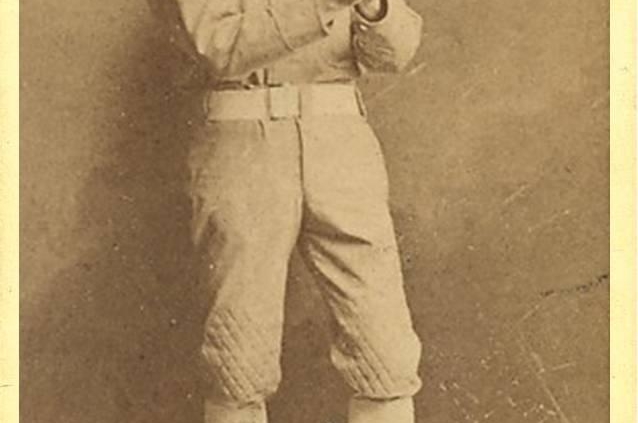

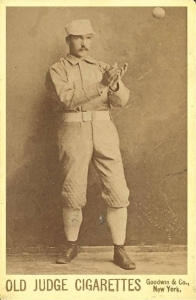

Largely overlooked today, George Van Haltren was a speedy center fielder who batted .316 on 2,544 hits during his 17-year big-league career. Described by historian Bill Lamb as “late 19th-century baseball’s premier leadoff man,” Van Haltren averaged almost a run scored per game during his prime as a five-tool player.1

Largely overlooked today, George Van Haltren was a speedy center fielder who batted .316 on 2,544 hits during his 17-year big-league career. Described by historian Bill Lamb as “late 19th-century baseball’s premier leadoff man,” Van Haltren averaged almost a run scored per game during his prime as a five-tool player.1

But his reputation as a hard-throwing southpaw actually stamped his ticket to the majors. As Lamb explained, Van Haltren garnered attention with his twirling performances in his hometown of Oakland, California, and the Bay Area against a barnstorming group of major leaguers in the 1886-1887 offseason. The Pittsburgh Alleghenys offered him a contract, but he decided not to travel east because of his mother’s ill health. He was eventually traded from the Alleghenys to the Chicago White Stockings for Jim McCormick and he reported to that club in May 1887. The 21-year-old posted an 11-7 record as the team’s third pitching option; he played 20 games in the outfield but batted an abysmal .203. Player-manager Cap Anson expected more from the Californian in 1888.

The White Stockings seemed primed to capture their sixth pennant of the decade (1880-1882, 1885-1886) when they returned to the Windy City after a 15-game road trip for a four-game series against manager Horace Phillips’s sixth-place Alleghenys. Behind Pud Galvin, who ended the season as the big leagues’ leader in career victories (305), the men from the Steel City opened the series on June 20 by shutting out Anson’s squad, 5-0. With his team’s lead over the second-place Detroit Wolverines cut to three games, Anson sent Van Haltren to the mound in the second game.

Chicago was at the center of America’s attention during the summer solstice, but not because of baseball. Two and a half miles due east of West Side Park, the White Stockings’ wooden ballpark, the Republican Party was staging its presidential nominating convention (June 19-June 25) at the Auditorium Building on Michigan Avenue. Designed by Louis Sullivan and Denkmar Adler, the building was the tallest in the city and largest (in square footage) in the country. The convention resulted in the nomination of Benjamin Harrison, who went on to be elected in November.

“[O]racles predicted rain,” quipped the Chicago Tribune about the weather for that Thursday afternoon, “consequently the timid base-ball enthusiasts concluded to stay down-town and read bulletins of the convention.”2 Nonetheless, 6,000 patrons braved temperatures approaching 90 degrees, oppressive humidity, and ominous skies to take in the national pastime.3

The game unfolded as a pitchers’ duel. At the time, pitchers threw from a 5½-foot-long by 4-foot-wide box, the front of which was just 50 feet from home plate.4 Van Haltren breezed through the first three innings, retiring seven of the nine batters he faced on grounders.

Toeing the rubber for Pittsburgh was Ed “Cannonball” Morris, who had won 114 games in his first three seasons (1884-1886) as arguably the best pitcher in the American Association. In 1887, the Alleghenys moved to the NL; however, Morris struggled while transitioning to a rule change that required pitchers to start their delivery with one foot on the back line of the pitcher’s box and permitted only one step forward. After a poor season (14-22), Morris had reemerged in 1888 and eventually ended the season with a 29-23 record.

Tom Burns collected the White Stockings’ first hit, a single to lead off the third. He moved to second on Van Haltren’s single to short center field, and then stole third. Tom Daly hit what appeared to be a tailor-made double-play grounder to second baseman Fred Dunlap, who fumbled the ball, enabling Burns to score. Van Haltren and Daly moved up a station on Jimmy Ryan’s fly out to left field. Dunlap juggled Marty Sullivan’s chopper for his second error of the inning, loading the bags. According to the Pittsburgh Post, Duke Farrell attempted a squeeze bunt which third baseman Elmer Cleveland fielded and threw home to catcher Jocko Fields to erase Van Haltren for the second out.5 With the bases still filled, Anson hit a tapper back to Morris for an easy out.6

The Ansonites, as they were sometimes called, missed an opportunity to tack on another run or two in the fourth inning. Fred Pfeffer smashed one into the gap and ran like a rabbit past second and was apparently quite salty when he was thrown out trying to extend his hit into a triple. Ned Williamson followed with another two-bagger but was left stranded on the keystone sack.

The Alleghenys had only two baserunners in the game. In the fourth, Anson committed a double error, muffing Fields’s one-out grounder and then throwing wildly as Van Haltren covered first base. In the following inning, Van Haltren walked Bill Kuehne, who stole second but was stranded there.

While Van Haltren set down the Alleghenys one-two-three in the sixth and seventh innings, the skies had become darker, temperatures had dropped more than 10 degrees, and rain seem imminent. In the bottom of the frame, the White Stockings “began to pound Morris,” reported the Tribune.7 Van Haltren spanked a triple into the left-center-field gap and then scored on Daly’s single. With Ryan at the plate, the skies opened, unleashing a torrent of rain and sending the players to their dugouts.

After waiting the required 20 minutes with no change in the downpour, umpire Lynch declared the game official at 3:30. Skipper Phillips and his players protested, but Anson refused to wait any longer than the mandated time. The Inter-Ocean of Chicago opined that the White Sox were lucky that the rain didn’t stop. “It is more than likely that the Pittsburg batsmen would have pounded Van Haltren’s lovely curves. … He does not seem able to master a wet ball.”8 So much for confidence from the hometown sportswriter. The Pittsburgh Post agreed, asserting that the Alleghenys “knew that if the game was continued after the rain, Van Haltren’s curves would be easily hit. Anson knew it, too.”9

Because the seventh inning was not completed, action from that frame was wiped off the record books and the White Sox officially won the game, 1-0, in 1 hour and 5 minutes.

Van Haltren was credited with a no-hitter, albeit an abbreviated six-inning, rain-shortened no-no. More than a century later, Van Haltren’s name was scrubbed from the list of pitchers with no-hitters when the Committee for Statistical Accuracy, in September 1991, changed the definition of a no-hitter to include only those games that last at least nine innings and end with no hits. An estimated 36 shortened no-hitters were removed, including Van Haltren’s.

Epilogue: Van Haltren completed the season with a 13-13 record as the White Stockings’ third starter behind Gus Krock (25-14) and Mark Baldwin (13-15). However, he showed promise at the plate, batting a robust .283, and tied for the team lead with 14 triples; and in the outfield, where he played in 57 games. Recognizing Van Haltren’s potential as a hitter, Anson moved him exclusively to the field in 1889 (as a center fielder, plus a handful of games at second base and shortstop). He responded by hitting .322 and scoring 126 runs. Van Haltren had one more shot at pitching, posting a 15-10 record with the Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders in the upshot Players’ League in 1890. Thereafter he emerged as one of baseball’s most exciting offensive catalysts and center fielders. He finished his pitching career with a 40-31 record, including a no-hitter recognized for 103 years.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 Bill Lamb, “George Van Haltren” SABR BioProject. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/george-van-haltren/.

2 “The Swallowtails Won,” Chicago Tribune, June 22, 1888: 6.

3 “The Weather,” (Chicago) Inter-Ocean, June 22, 1888: 7.

4 John Thorn, “Pitching: Evolution and Revolution,” Our Game. Origins, August 6, 2014. https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/pitching-evolution-and-revolution-efd3a5ebaa83; Erik Miklich, “The Pitcher’s Area,” 19cbaseball.com. http://www.19cbaseball.com/field-8.html.

5 “Anson Gets Even,” Pittsburgh Post, June 22, 1888: 6.

6 The Tribune seemed to confuse the final sequence of at-bats. The newspaper omitted Farrell’s at-bat and reported that Van Haltren broke for home with Anson at the plate. Anson swung and missed; Van Haltren attempted to return to the bag, but Fields had rifled a bullet and Cleveland tagged him for the second out. However, that could not have been the second out if the bags were already filled for Farrell.

7 “The Swallowtails Won.”

8 “Calcimine for Pittsburgh,” (Chicago) Inter-Ocean, June 22, 1888: 6.

9 “Anson Gets Even.”

Additional Stats

Chicago White Stockings 1

Pittsburgh Alleghenys 0

6 innings

West Side Park

Chicago, IL

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.