June 8, 1885: Presto Change! Cannonball Morris dominates after overhand pitching is suddenly legalized

Ulysses S. Grant said, “I know of no method to secure the repeal of bad or obnoxious laws so effective as their stringent execution.”1 His sentiment rang true in major-league baseball after the American Association and National League repealed rules that limited pitching motions in the midst of the 1885 season. The change unleashed pitch velocities and brought immediate success to one Pittsburgh pitcher whose high-profile run-in with the AA’s pitching-motion rule hastened its demise.

Ulysses S. Grant said, “I know of no method to secure the repeal of bad or obnoxious laws so effective as their stringent execution.”1 His sentiment rang true in major-league baseball after the American Association and National League repealed rules that limited pitching motions in the midst of the 1885 season. The change unleashed pitch velocities and brought immediate success to one Pittsburgh pitcher whose high-profile run-in with the AA’s pitching-motion rule hastened its demise.

In December 1882, National League owners revised their pitching rules to specify that “[the pitcher’s] hand, in delivering the ball, must not pass above the line of his shoulder.”2 This reflected the perspective that a pitcher’s role should be to deliver a “fair ball” to the batter, suitable for striking into the field of play. The newer Association, preparing for its second season, followed suit, requiring pitches to pass “below the line of [the pitcher’s] shoulder.”3 Throughout the ensuing season, NL and AA umpires struggled with enforcing the shoulder-based pitching restrictions, leading to incessant “kicking” by players, captains, managers, and fans.

As part of a broader effort to reduce in-game turmoil, NL owners removed the prohibition against overhand pitching for the 1884 season.4 This ushered in the year of the pitcher.5 The number of NL shutouts increased to 70 from 38 the year before, and strikeouts per nine innings rose 30 percent. The Providence Grays’ ace hurler, Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn, won 60 games and fanned 441 batters, both NL records. The club’s backup pitcher, Charlie Sweeney, fanned 19 in a nine-inning game. The overall NL batting average dropped from .262 to .247 and runs per game fell from 5.78 to 5.51. The Boston Journal wrote that fans lost interest from “the lessening of batting,” and said it was time to end the “experiment.”6 To diminish prominence of the “pitcher’s game,” the New York Sun urged the NL to revise its playing rules and the AA to boost enforcement of its still-in-place overhand pitching prohibition.7

In November 1884 NL owners mandated that pitchers must have “both feet touching the ground while making any of the motions made by him in pitching.”8 AA owners again chose not to adopt this newest NL pitching rule, believing it prevented pitchers from being able to throw curveballs. They kept the below-the-shoulder rule in place for the 1885 season.9

Sentiment for the NL’s two-feet-down rule was positive at first. Chicago White Stockings player/manager Cap Anson endorsed the change, while acknowledging that pitch speeds would suffer.10 Philadelphia Quakers manager Harry Wright believed the rule would improve competitive balance across the league, and possibly even boost the number of triple plays.11 It made no difference to Buffalo Bisons ace Pud Galvin, who said, “I can stand on my head, if necessary, and pitch.”12

Once preseason play began in 1885, the absurdity of the two-feet-down rule became apparent. 13 Umpires were confused and pitchers were getting hurt.14 The seemingly indestructible Radbourn complained of a lame back after a week’s trial.15 White Stockings ace Larry Corcoran was confident he wouldn’t last long under the strain of pitching with both feet down. Every day more and more baseball men of prominence were calling for the rule’s demise.16 Anson and Wright reversed course and called for it to be revoked.17 Two days into the season, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat asserted that pitchers and the public hated the rule.18 Shortly thereafter, NL umpires decided to change the penalty for an illegal pitch and ignore lifting of the pitcher’s back leg, which likely created more confusion and frustration.19

Meanwhile, the American Association was also having trouble with its below-the-shoulder rule. Despite the Association’s commitment to strictly enforce the rule since its introduction two years earlier,20 compliance had become inconsistent. On May 26 the Eastern League poked a stick in the Association’s eye by electing to abolish the “obnoxious pitching restriction,” which it had copied from the AA.21 On June 3 Sporting Life insisted that “below the shoulder must go” as it “has been a growing germ of ill-feeling between … captains … umpires and the audiences.”22

AA owners scheduled a meeting to vote on allowing “high-arm pitching,”23 but the NL determined the fate of its unpopular pitching rule first. The NL revoked its two-feet-down rule at an emergency meeting on June 7.24 The next day, the AA revoked its below-the-shoulder rule.25 Now any pitching motion was acceptable in both major leagues provided the pitcher was within the pitching box when releasing the ball. The NL change was effective June 9, the AA change effective immediately. 26

The Brooklyn Grays hosted the Pittsburgh Alleghenys in one of four AA games played on June 8, the beginning of a new pitching era. The second-place Alleghenys had won two of three in their four-game series in Brooklyn, the first of four stops on a 13-game road trip.

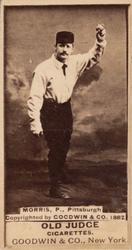

In the box for Pittsburgh in the series finale was second-year southpaw Ed “Cannonball” Morris, a rookie star in 1884 for the AA’s now-defunct Columbus Buckeyes, then drawn east when the Ohio club disbanded and Alleghenys’ manager Horace Phillips signed most of the defunct team’s players.27

Morris was a workhorse for Pittsburgh, starting and completing 20 of the team’s first 34 games. His record was 14-6, with 3 shutouts and a 16-inning victory in Cincinnati that the Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette called “one of the most remarkable ever played there.”28

Facing Morris for the sixth-place Grays was Henry Porter. The emerging ace of the Brooklyn staff, Porter was 6-4 heading into the contest. This was his fourth start of the season against Morris. Porter had lost to Morris in Pittsburgh on May 14 and in the opener of this series,29 but had triumphed over Morris two days earlier.

Morris was nicknamed Cannonball for the ferocity of his pitches, but it was his temper that exploded in the June 6 game. Angry after being called for “overthrowing” (pitching overhand), he “grew wild” and suffered a 13-2 thrashing from the Grays.30 In its summary of the game, the Brooklyn Union made it clear it wasn’t the first time Morris had lost his temper while in the box.31

Morris’s struggles with the below-the-shoulder rule were nothing new. In early May of 1884, a balk called on him for violating that rule in the 10th inning of a tie game with the St. Louis Browns put the eventual winning run on first base.32 Three weeks later, Morris tossed a no-hitter against the Alleghenys, who claimed Morris was throwing overhand.33 That outing became even more controversial when the New York Clipper quoted umpire John Valentine as admitting he’d allowed Morris to pitch overhand because he’d seen another umpire allow it.34 John “Kick” Kelly, the umpire named by Valentine, denied he’d allowed any pitcher to throw illegal pitches.35 This embarrassing episode may well have contributed to the AA’s decision to allow overhand pitching 12 months later.36

Cannonball, a Brooklyn native, must’ve been anxious to wipe away the memory of his Washington Park debacle and validate the Brooklyn Union’s prediction that he would “come out strong” now that overhand pitching was allowed.37

Weather for the June 8 game at Washington Park was clear, with the temperature 80 degrees by midday.38 Pittsburgh tallied the game’s first run in the top of the second inning. First baseman Jim Field drew a walk from Porter, advanced to third on a single by backup catcher Rudy Kemmler,39 and scored on a muff by second baseman George Pinkney on a thrown ball.

A fine running catch by Brooklyn center fielder Pete Hotaling in the seventh inning kept the score 1-0, but the Grays couldn’t mount a serious threat against the “terrible force” of Morris’s “swift pitching.”40 The Alleghenys scored their second and final run in the eighth inning, when Liverpool native Tom Brown41 singled to drive in Leipzig native Bill Kuehne after he’d tripled.42 A “clever” double play started by shortstop Germany Smith kept Pittsburgh from scoring any more that inning.43 Morris scattered three walks and two hits, singles by Ed Swartwood44 and Bill McClellan, in cruising to a 2-0 shutout, with six strikeouts.45

Afterward the Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette offered that “Morris … seems to have been greatly benefited by the new pitching rule.”46 The Brooklyn Union called the rule change “disastrous to the Brooklyns” and suggested that the Grays need only “[strike] the ball with ease, using a twist … for a slight knock will carry one of those swiftly pitched balls a great distance.” The Brooklyn Eagle recommended practice hitting against “straight throwing to teach them wrist play at the bat against swift pitching.”47

Morris finished the year 39-24 and led the AA in complete games (63), innings pitched (581), strikeouts (298), shutouts (7), fewest hits per nine innings (7.1), WHIP (0.964), and pitcher WAR (12.7).48

The various major leagues have made many pitching-related rules changes since 1885.49 Allowing batters to call for high or low pitches was abolished, the number of balls required for a base on balls was reduced, the pitching box was resized and then eliminated (replaced by a rubber slab, located 60 feet 6 inches from home plate), and pitches with an intentionally defaced ball were outlawed. But never again did a major league dictate how a ball could be pitched.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

The author utilized Base Ball’s 19th Century ‘Winter’ Meetings: 1857-1900 (Phoenix: SABR, 2018), as well as game summaries and box scores for the June 4-8 Pittsburgh vs. Brooklyn series published in the Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, New York Clipper, Brooklyn Union, Brooklyn Eagle, New York Sun, New York Times and Sporting Life, and the same newspapers to compile 1885 pitching logs for Morris and Porter. He also obtained pertinent material from Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 First Inaugural Address of Ulysses S. Grant, March 4, 1869, Yale Law School Avalon Project website, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/grant1.asp, accessed April 5, 2022.

2 The intent of this rewording was to allow any arm angle below shoulder height as well as to allow pitches that entailed a snap of the wrist, commonly referred to as “jerks.” “The League Convention,” New York Clipper, December 16, 1882: 629.

3 “The American Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 23, 1882: 645.

4 Michael R. McAvoy, “Boom and Entry: The 1883 Business Meetings,” in Base Ball’s 19th Century ‘Winter’ Meetings: 1857-1900 (Phoenix: SABR, 2018), 203; “The League Convention,” New York Clipper, December 1, 1883: 609.

5 Hall of Fame historian Lee Allen considered 1884 the “greatest season for pitching the game has ever known.” Joseph Overfield, “A Memorable Year: 1884; A Memorable Player: Jim Galvin, Baseball Research Journal, 1982, https://sabr.org/journal/article/a-memorable-year-1884-a-memorable-player-jim-galvin/.

6 “Base Ball Records,” Boston Journal, October 16, 1884: 5.

7 “Base Ball,” Providence Evening Bulletin, November 18, 1884: 3.

8 “The League Meeting,” Sporting Life, November 26, 1884: 8.

9 “Important Changes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 12, 1884: 5.

10 “The Domain of Sports,” Chicago Daily News, December 10, 1884: 1.

11 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Times, December 21, 1884: 10; “Harry Wright on Base Ball,” Cambridge City (Indiana) Tribune, January 8, 1885: 1.

12 “Sporting,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, December 6, 1884: 3.

13 An early indication of widespread problems with the NL’s new pitching rule was the many exhibition game losses to AA teams, whose pitchers had the comfort of following pitching restrictions that were unchanged from the previous season. “Base Ball Notes,” Norfolk Virginian, April 21, 1885: 1.

14 League President Nick Young dutifully distributed preseason guidance on how umpires were to enforce the rule. Despite his clarification that umpires need only watch the pitchers’ feet and pay no attention to their arm movements, NL umpire Harry McCaffery refused to enforce the new rule in a preseason game, admitting he didn’t fully understand it. “The National Game,” Burlington (Vermont) Clipper, March 26, 1885: 4; “The League Pitching Rules Defined,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 5, 1885: 8.

15 “Base Ball,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Daily Herald, May 28, 1885: 2.

16 During the last week of the NL preseason, the St. Louis Globe Democrat reported that the Detroit Wolverines had forwarded a request to President Young that the new pitching rule not be enforced, the Minneapolis Star Tribune claimed that Quakers pitcher Charlie Ferguson threatened to quit if the rule was enforced, and the Boston Globe wrote that Providence captain Joe Start wanted the new pitching rule revoked. “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 25, 1885: 7; “Baseball Gossip,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, April 26, 1885: 19; “Home Runs,” Boston Globe, April 29, 1885: 5.

17 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, April 19, 1885: 2; “Diamond Chips,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 29, 1885: 7.

18 “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 3, 1885: 8.

19 The penalty change made the warning, referred to as the first foul balk, a dead ball so as not to reward pitchers whose illegal offerings resulted in strikeouts or outs in the field. “Sporting Notes,” Ottawa (Ontario) Daily Citizen, May 9, 1885: 7.

20 “Meeting of American Association Umpires,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 20, 1883: 6.

21 The Eastern League had elected in its January 1884 organizing meeting to adopt AA playing rules. McAvoy, “Boom and Entry,” 205; “The Obnoxious Pitching Restriction Abolished,” Providence Evening Bulletin, May 27, 1885: 5.

22 “A Change Needed,” Sporting Life, June 3, 1885: 3.

23 “An Effort to Remove the Restrictions on the American Association Pitchers,” Philadelphia Times, May 30, 1885: 2; “Sports and Pastimes,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 6, 1885: 1.

24 “The Pitching Rule Revoked,” Boston Globe, June 7, 1885: 3.

25 At their meeting, AA owners also eliminated foul bounds, requiring that balls be caught on the fly in the outfield to be counted as putouts. “Sporting,” Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1885: 3.

26 The NL implemented the change after President Young had received telegrams from representatives of the Boston and Providence clubs confirming their votes to eliminate restrictions on pitching motions. “Presto, Change!” Sporting Life, June 17, 1885: 2.

27 Morris was one of 10 Buckeyes reassigned to Pittsburgh after the collapse of the Columbus franchise.

28 The game story also credited Pittsburgh first baseman Jim Field with a record 29 putouts. “Pork Comes Down,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, April 25, 1885: 6.

29 The Brooklyn Eagle called the series opener “wearisome and unattractive,” claiming the umpire allowed both Porter and Morris to violate the soon-to-be-abandoned below-the-shoulder pitching rule. In contrast, the Brooklyn Union called the game “brilliant,” with frequent applause from the crowd for a game “evidently greatly enjoyed.” In fact, the game was a see-saw battle with four lead changes, the last when Morris scored the go-ahead run in the bottom of the eighth after he’d tripled. “Sports and Pastimes,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 5, 1885: 1; “Base-Ball,” Brooklyn Union, June 5, 1885: 2.

30 “Base Ball,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, June 8, 1885: 8; “Base on Balls Records,” Baseball Almanac website, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/recbooks/walks_by_pitchers_records.shtml, accessed April 11, 2022.

31 Morris was also described as angry in the Brooklyn Union account of the first game of the Brooklyn series. “Base-Ball Games,” Brooklyn Union, June 7, 1885: 8; “Base-Ball”: 2.

32 AA umpires were instructed to warn a pitcher at the first instance of delivering a pitch to a batter that violated the arm height rule. On the second violation, a balk was typically called, with the batter awarded first base. “The New American Rules,” New York Clipper, April 5, 1884; “St. Louis vs. Columbus,” New York Clipper, May 17, 1884: 136.

33 “Allegheny vs. Columbus,” Sporting Life, June 4, 1884: 3.

34 New York Clipper, June 7, 1884: 179.

35 “Specks of Sport,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 7, 1884: 12.

36 The fact that Valentine was the umpire who called the crushing balk on Morris in the earlier game may have played into his actions during the no-hit game but there’s no hint of that in newspaper stories published about the controversy.

37 Conversely, the Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette identified the Grays’ Henry Porter, and Alleghenys occasional starter Frank Mountain as pitchers who would “very much benefit” from eliminating the requirement to pitch below the shoulder, without mentioning any benefit to Morris. Brooklyn Union, June 7; “Base Ball Changes,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, June 8, 1885: 8.

38 “The Weather Indications,” New York Times, June 9, 1885: 2; “The Weather Report,” New York Tribune, June 9, 1885: 5.

39 The Alleghenys’ regular catcher, Fred Carroll, was unable to play during the Brooklyn series after splitting a finger in a game a week earlier. Carroll was Morris’s longtime regular catcher, going back to their days together on the 1882 Reading Actives of the Interstate Association, and his brother-in-law. Morris married Carroll’s sister, on Valentine’s Day 1885. “Phillip’s Pets,” Sporting Life, June 3, 1885: 7; “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, May 6, 1885: 7.

40 “Base-Ball,” Brooklyn Union, June 9, 1885: 7.

41 Brown, the first of four major leaguers named Tom Brown, enjoyed a major-league career longer than that of any other player born in England (17 seasons, playing in close to 1,800 games).

42 In the third of four consecutive seasons in which he stroked more triples than doubles, Kuehne became known as “Dreisocker,” the German word for (baseball) triple. David Nemec, “Bill Kuehne,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bill-kuehne/.

43 The Brooklyn Eagle remarked that Germany’s play “reached that of his namesake at second base on the other side,” Charles “Pop” Smith. Pop was the reigning AA leader in assists for a second baseman, who repeated the feat in 1885 and posted the highest range factor of any AA second baseman that season. Germany went on to lead AA shortstops in assists and range factor in 1885 and had the highest defensive WAR (2.4) of any AA player that season. “Sports and Pastimes,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 9, 1885: 2; “Base-Ball.”

44 Swartwood had the distinction of being the only batter to reach base, hit by a pitch, in Al Atkinson’s no-hitter and near-perfect game on May 24, 1884. Brian McKenna, Ed Swartwood SABR bio, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ed-swartwood/.

45 Three of those strikeouts were by Grays first baseman Bill Krieg, a backup catcher filling in for slick fielding “Silver Bill” Phillips, the first Canadian to play in the major leagues, who’d been injured a few days earlier. “Base-Ball,” Brooklyn Union, June 3, 1885: 8; William Akin, Bill Phillips SABR bio, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bill-phillips/.

46 “Morris Was Meant,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, June 9, 1885: 8.

47 “Sports and Pastimes.”

48 Sadly, overuse ended Morris’s career before he turned 30. Nineteenth-century baseball historian and SABR Henry Chadwick Award winner David Nemec has called Morris “the first truly outstanding southpaw pitcher in major league history.” David Nemec, The Beer and Whiskey League (New York: Lyons and Burford, 2004), 65.

49 “Baseball Rule Changes,” Baseball Almanac website, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/rulechng.shtml, accessed April 9, 2022.

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Alleghenys 2

Brooklyn Grays 0

Washington Park

Brooklyn, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.