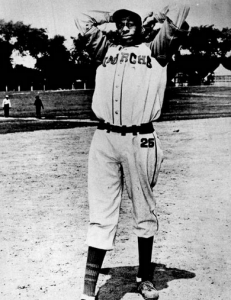

May 24, 1942: Paige, Monarchs get the best of Dizzy Dean All-Stars at Wrigley Field

On this crisp afternoon, the sky was a vivid blue, the grass and ivy were a radiant green, and the infield dirt was a golden brown. One color, though, was making its debut at Wrigley Field. For the first time, a Black baseball team would play in the famous ballpark, a hallmark of racially segregated north Chicago. Its southern cousin, Comiskey Park, venue for the Chicago American Giants, had previously hosted the Negro League East-West All-Star games and other Black-White contests.

On this crisp afternoon, the sky was a vivid blue, the grass and ivy were a radiant green, and the infield dirt was a golden brown. One color, though, was making its debut at Wrigley Field. For the first time, a Black baseball team would play in the famous ballpark, a hallmark of racially segregated north Chicago. Its southern cousin, Comiskey Park, venue for the Chicago American Giants, had previously hosted the Negro League East-West All-Star games and other Black-White contests.

With many big leaguers swapping their wool uniforms for Army fatigues, White owners felt exhibition games would draw a big crowd, regardless of the race. Against this backdrop, 29,775 souls packed box seats, grandstands, and bleachers to see two living legends, Satchel Paige and Dizzy Dean. The nation had been at war for only half a year but any opportunity to disconnect from the event, if only for a few hours, was a welcome respite for its citizens.

Modern fans regard exhibition games as anachronisms. We are privy to spring training, where teams try new players and get their expected starters into playing shape. They are not meaningless but rather necessary exercises, like a cardio session before serious weight-lifting. The Harlem Globetrotters and their hapless rivals, the Washington Generals, typically play in front of sparse modern crowds as the present-day NBA, with its interminable playoff contests, captures the attention of the basketball fans. But back in the pre-television era, Dean and Paige traveled south, west, or any other direction where the weather was hospitable enough to don their uniforms, entertain crowds, and fatten their pockets.

The two had first locked horns on October 16, 1933, with phenomenal success at the ticket office to ensure various sequels. Others followed, with a 1934 dress rehearsal, not in the Midwest but rather in the facsimile Wrigley Field of Hollywood, California, pitting the two aces as part of the Dizzy and Daffy Dean Barnstorming Tour. Dizzy’s arm injury ended the partnership, which was then transferred to Bob Feller. On May 23, 1942, the New York Times failed to note the history, with the fifth and last sentence of its story meekly noting that the Dean All-Stars would face the Monarchs.1

Fans expecting to see Feller – arguably the best hurler in the majors at the time – were disappointed when the Army canceled his previously granted leave. While the military decision was final, many wondered whether a dislike for such Black-White competition from Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis was to blame. A major leaguer by age 17, an All-Star at 19, a 20-game winner by 20, and possessing 100 career victories by 22, Feller was among the first professional athletes to enlist in the armed forces after the attack on Pearl Harbor. His promise to donate his appearance fee for this game to the Navy Relief Fund had earned accolades; his willingness to appear against Paige ensured that the integrated crowd would be treated to a spectacle.

Playing as the visitors, the Monarchs rode not just Paige’s strong arm but also his experience. He did not seek to mow down every opponent but instead sought to “pitch to the batter’s weakness.”2 Across the diamond, Dean pitched one flawless inning before yielding to Johnny Grodzicki, who had debuted with the Cardinals in 1941 and compiled a 1.35 ERA in five games. While stationed at Fort Knox for training, Grodzicki participated in various exhibition games before being deployed to Europe. Wounded in Germany in 1945, he won a Purple Heart for his service and returned to the majors a year later.3

After retiring the big leaguers with ease in the first two frames, Paige allowed an unearned run in the third. A slow roller by former Yankee, Dodger, and St. Louis Brown Joe Gallagher yielded the first baserunner; he advanced to third on Grodzicki’s bunt when Buck O’Neil uncharacteristically did not cover the base on time. Emmett “Heinie” Mueller knocked in Gallagher with a groundball to put the All-Stars on top. Both Gallagher, who was drafted into service in 1941, and Mueller, who joined in 1942 served in Jefferson Barracks, Missouri.4 Neither one would return to the big leagues after the war.

In the fourth, Herb Cyrus (aka Herb Souell and Baldy), a capable third baseman who appeared in several Negro League All-Star games by the decade’s end, was driven in by slugger Willard Brown. Brown, a multiple all-star in the Negro Leagues and future record-holder of many Puerto Rican Winter League records (where he is still known as “ese hombre” or “that man”), also served in the European Theater prior to the war’s end.5 His brief, unsuccessful major-league career did not taint his overall credentials, and he was belatedly inducted into Cooperstown in 2006.

No further excitement ensued until the Monarchs’ James Joe Greene (a.k.a. Pea, Pig, and Green) doubled with two outs in the sixth. Greene, a power-hitting catcher through most of the 1940s, served in Italy; his regiment was tasked with procuring the body of fallen Italian ruler Benito Mussolini after the despot’s execution by partisans.6 Paige, having given his team – and more importantly, the paying public – six strong innings, was lifted for Hilton Smith. Smith, a right-handed hurler, often relieved Paige in such exhibitions, but was himself a commanding presence on the mound, earning induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2001.

Al Piechota, the third pitcher for the All-Stars, allowed a single to speedster Willie “Bill” Simms, who reached third after a bunt and a fly ball. Piechota played in the majors in 1940 and 1941 before serving in the military while stationed at Michigan and Indiana bases. With two outs, Brown walked and stole second before Greene drove in both runners with a line-drive double, adding both the winning and insurance runs.

While the African American press front pages lauded the Monarchs’ victory, crafting detailed columns on the game’s play and atmosphere, the White newspapers provided the bare minimum. If history is written by the winners, no one bothered to tell the mainstream media.

The New York Times mentioned the attendance and named a dozen of Dean’s teammates; from the Monarchs, only Paige was noted.7 The Sporting News literally buried the story, giving it one-sixteenth of a page, including the box score.8 The weekly was far from impartial, as its opposition to integration was well-known. In 1945 it gave Yankees President Larry MacPhail the opportunity to discuss his stance, as requested by New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. In a half-page op-ed, McPhail fulminated, “there is not a single Negro player with major league possibilities in 1946.”9 Echoing the decades-old unwritten rule, he concluded, “I have no consistency in saying the Yankees have no intention of signing Negro” by arguing that “the Negro Leagues cannot exist without good players.”10 Roughly two weeks later, under a condescending editorial, it observed that “(Jackie) Robinson, at 26, is reported to possess baseball abilities which, were he white, would make him eligible for a trial with, let us say, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Class B farm at Newport News, if he were six years younger.” Despite being the nation’s undisputed sports journal, it had somehow failed to notice Robinson’s torrid performance with the Kansas City Monarchs, given his .414 batting average in 63 plate appearances. His .349 mark with Montreal of the International League in his sole minor-league campaign would further demonstrate the absurdity of the statement. 11

Perhaps it was consolation to see the dark ink printed on the pale newspaper stock, symbolizing the superiority of the Monarchs.

The weekly Baltimore Afro-American published an in-depth account of the game, saying it was “one of the most exciting contests held at the Clubs’ [sic] park for some time,” and adding, “People came from far and near, including Atlanta, to watch the contest.”12 The newspaper was also eager to publicize the repeat engagement, scheduled for May 31, pitting the Dean All-Stars against the Homestead Grays in Washington, DC.

Despite consistent efforts by the Black press to cajole the big leagues to integrate, the commissioner, team owners, civic leaders, and even prominent players managed to stifle progress. Baseball fans eager to see the best athletes on the field, regardless of race, were left with barnstorming competitions to quench their thirst until 1947. Instead, such events whetted their appetite by expanding the “what ifs” into reality. The Chicago Defender’s account sought to further the argument, stating, “[T]he crowd was there to see Paige tame the major leaguers … and that’s what happened … and no one could blame them. There were their own boys, playing on big league grounds, performing in big league style – yet these same players are denied the right to earn a good living at their profession.”13

Opinion writer Fay Young juxtaposed the quality of the product, acerbically writing that “the White Sox were taking a 14 to 0 licking in one game of the double header at Comiskey Park” and “brown American fans are baseball hungry but are sick of paying their hard-earned money to see second rate performers.” 14

After the game, Dean returned to the broadcast booth, covering games for both St. Louis franchises before appearing in one final big-league contest on September 28, 1947. After stating that he could pitch better than the Browns’ sorry staff, he backed up his claim by tossing four innings without allowing a run. Feller earned eight battle stars for his military service before returning to the majors in late 1945. Paige eventually made it to the big leagues, joining Feller on the 1948 World Series champion Cleveland Indians. All three were selected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Acknowledgments

Josh Mabe, newspaper librarian for the Harold Washington Library, Chicago, for providing the Chicago Defender articles.

Notes

1 “Dizzy Dean Pitches Today,” New York Times, May 24, 1942: S3.

2 “Paige and Smith Tame Dizzy Dean’s All-Stars,” Chicago Defender, May 30, 1942: 19.

3 Gary Bedingfield, “Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice,” baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/wounded_in_combat/grodzicki-johnny.html.

4 “Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice,” baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/gallagher_joe.htm; baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/wounded_in_combat/mueller-heinie.html.

5 “Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice,” baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/brown_willard.htm.

6 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 1984), 337-8; Gary Bedingfield, “Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice,” baseballinwartime.com/negro.htm.

7 “Paige’s Team Tops Dean’s All-Stars,” New York Times, May 25, 1942: 19.

8 “Dean’s Service Team Loses,” The Sporting News, May 28, 1942: 15.

9 Larry MacPhail, “MacPhail for Sound Plan to Qualify Negroes in O.B.,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1945: 14.

10 “MacPhail for Sound Plan to Qualify Negroes in O.B.”

11 “Montreal Puts Negro Player on Spot,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1945: 12.

12 R.S. Simons, “Satchel Allows All-Stars Only 2 Hits in 6 Innings,” Baltimore AfroAmerican, May 30, 1942: 27.

13 “Paige and Smith Tame Dizzy Dean’s All-Stars.”

14 Fay Young, “Through the Years,” The Chicago Defender, May 30, 1942: 19.

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.