May 31, 1938: Lou Gehrig plays his 2,000th consecutive game

On May 30, 1938, some 81,000 people crammed into Yankee Stadium for a Yankees-Red Sox doubleheader, possibly the biggest crowd in baseball history up to then. The home fans got what they wanted, a Bronx Bombers sweep, powered by four hits and four RBIs from Lou Gehrig, who was climbing out of a disconcerting early-season slump. The next day emerged sunny and warm in New York, perfect for baseball, and as all the newspapers announced, Gehrig was about to play in his 2,000th consecutive game, a feat the Associated Press trumpeted as “the greatest endurance record in sports,”1 and the New York Times called “a record which probably never will be surpassed.”2

wanted, a Bronx Bombers sweep, powered by four hits and four RBIs from Lou Gehrig, who was climbing out of a disconcerting early-season slump. The next day emerged sunny and warm in New York, perfect for baseball, and as all the newspapers announced, Gehrig was about to play in his 2,000th consecutive game, a feat the Associated Press trumpeted as “the greatest endurance record in sports,”1 and the New York Times called “a record which probably never will be surpassed.”2

How odd then that May 31, 1938, could have been mistaken for any other afternoon in the Bronx. A crowd of just 6,917 turned out to see the Iron Horse make history. The Yankees made no special effort to promote Gehrig’s achievement, and held only a small pregame ceremony that was not broadcast over the stadium’s PA system. You could call it Lou Gehrig Under-Appreciation Day.

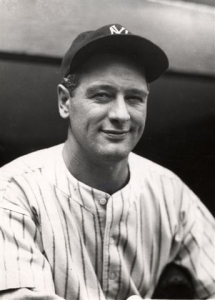

Gehrig certainly deserved more. He was in the midst of his 14th season as the Yankees’ first baseman and had already racked up most of the 493 home runs and 1,995 RBIs that would land him in the Hall of Fame. As early as 1932, Grantland Rice, the nation’s most prominent sportswriter, had named him the most valuable first baseman in baseball history. Since then, Gehrig had won two more home-run titles (in 1934 and 1936), the Triple Crown, and an MVP award, and led the Yankees to World Series wins in 1936 and 1937, the fourth and fifth championships of Gehrig’s career.

But there would have been no ceremony at all if Gehrig’s wife, Eleanor, had her way. She later said that the night before the game, she pushed Lou to abruptly end the streak. She argued that skipping the game would annihilate the charge, hurled by New York sportswriters, that Lou lacked color, that prized, amorphous quality that generated stories and sold newspapers.

“If you don’t play,” she said, “they’ll write about you for days and everybody will say, ‘That’s some colorful ballplayer.’ And if you do play, you know what you’ll get out of it — a paragraph [in the papers] and a floral horseshoe.”3 Giant floral horseshoes were a common if impractical gift given to ballplayers in the pre-World War II era.

Gehrig didn’t buy his wife’s logic. The Yankees had planned the ceremony, after all. “I can’t just walk out on them,” he said.4

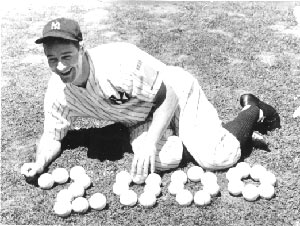

So the next morning, Gehrig drove to the stadium, suited up and walked onto the infield for the celebration, such as it was. Someone had arranged baseballs on the grass to spell out “2,000” and Gehrig sat down behind them for a few photographs. Next, he gathered with about 15 teammates near first base for the brief ceremony, captured by a Universal Studios newsreel camera.

A smiling manager Joe McCarthy gave Gehrig some typically low-key praise. “Lou, I want to congratulate you on a wonderful career and playing two thousand games without missing a game,” he said. “And I hope I’m around here when you play your next two thousand.”5

Gehrig shook McCarthy’s hand and said, “Thanks, Joe.” His teammates then raised their caps in tribute for a photo that ended up in the next day’s Times. That was it, the entire ceremony.

The milestone touched off a round of articles and sports-page cartoons about Lou and his streak. Most were laudatory, even reverent. But a few joined with Eleanor in calling for the streak to stop. Early in the season, Lou had struggled to push his batting average over .200, and observers thought he looked slow and awkward at bat and in the field. No one knew Gehrig was suffering early symptoms of ALS, the disease that would tragically kill him at age 37. His critics simply thought the streak was wearing him down.

“The darn thing’s gotta end some time,” wrote Lester Rodney in the Daily Worker, a communist paper with a sports section. “How about now, when you plainly show that you could use a rest, Lulu? Go fishing for a week and I’ll bet anyone in the office that you bat over .400 the first week you come back.”6

But Gehrig made it clear that the streak would go on. “If I’m out of even an exhibition game, I’m nervous,” he said. “I’d burn up more energy doing nothing, fishing or hunting, than playing ball.”7

Lou and his teammates couldn’t have been too nervous about that afternoon’s game. The Red Sox started Johnny Marcum, a journeyman right-hander whom the Yankees usually pounded like a punching bag. In 27 career appearances against the New Yorkers, Marcum had an ugly 6.71 ERA. He fared no better this day, as the Yankees leaped out to a quick 3-0 lead on solo home runs by Tommy Henrich and Bill Dickey and Frankie Crosetti’s RBI single after three innings.

Had the Yankees pitched one of their aces — Red Ruffing or Lefty Gomez — that might have been enough. But manager McCarthy sent 27-year-old rookie Joe Beggs to the mound for his fifth big-league start. From the start, Beggs struggled. In the first inning, the Red Sox put two runners on before he retired the side on Joe Cronin’s fly out. In the second, the visitors loaded the bases, only to see Doc Cramer hit a line drive at shortstop Crosetti, who caught it and tagged Eric McNair leaving second base for an unassisted double play.

Beggs’ luck ran out in the fifth, when catcher Gene Desautels walked, Marcum reached base on a fielder’s choice, and right fielder Red Nonnenkamp singled to drive in the Red Sox’ first run. After a walk to Joe Vosmik loaded the bases, up stepped Jimmie Foxx, in the midst of a 50-homer MVP season. Foxx slammed a fly ball down the right-field line, over Yankee Stadium’s short right-field wall. Gehrig, standing at first, thought the ball had curved foul. Umpire Cal Hubbard disagreed and signaled home run.8 Gehrig and catcher Dickey argued vehemently, and photographers caught them yelling at Hubbard, whose wide-open mouth suggested he was yelling right back.

As always, the ump’s verdict stood. Grand slam, Foxx. Score: 5-3 Boston.

There wasn’t much the Yankees could do in those pre-instant-replay days except to keep scoring. In the bottom of the fifth, Henrich cut the lead to one with an RBI single that scored Red Rolfe. In the sixth, Crosetti’s single pushed in Bill Knickerbocker. Red Sox manager Cronin pulled Marcum and sent in Fritz Ostermueller, who promptly gave up a two-run homer to Rolfe, putting the Yankees in front, 7-5. Myril Hoag and Knickerbocker padded the lead with back-to-back doubles in the seventh, adding a run.

Gehrig was a spectator to these rallies, managing only a meaningless walk in his first four at-bats. In the eighth, the Yankees captain finally contributed, with what the New York Sun called a “half-swing single into center.”9 A vicious drive it was not, but the hit knocked in Rolfe for the Yankees’ ninth run. The Yankees plated three more runs before the inning was over. Relief ace Johnny Murphy, who had come in for Beggs, set down the Red Sox in the ninth and earned the 12-5 victory.

The game ended somewhere in the 5 o’clock hour. In her memoir, Eleanor said Lou came home that night wearing an embarrassed grin and carrying a giant horseshoe of flowers, a sight that reduced her to uproarious laughter. And maybe he did, although photos and film of the day do not show Gehrig receiving such a gift.

What Eleanor didn’t mention is that on this evening Gehrig stayed out unusually late — not to celebrate his achievement, but to appear on nationwide network radio. Lou starred that night on the NBC program Ripley’s Believe It or Not! In the minds of the producers, a baseball player not missing a game for 13 straight years qualified as a believe-it-or-not event.

In the show, Gehrig played along with a recreation of the June 1, 1925, at-bat that launched his incredible streak.10 Host Robert Ripley set the scene:

RIPLEY: “Our scene opens in the Yankee dugout, as the players are seated on the bench waiting for their turn at bat. At one end of the bench, an anxious rookie is seated. Miller Huggins, the pint-sized manager of the Yankees, looks over his players. He needs a pinch-hitter, for the bases are loaded and the Yanks are behind. With a sudden inspiration, he nods to the rookie and says:9

HUGGINS (played by an actor): Hey you, big boy. Come here.

GEHRIG: Yes, sir! Want me to go in?

HUGGINS: Yeah, you’re going to go in as a pinch-hitter and you’ll play first base the next time around.

GEHRIG: Yes, sir! Anything else?

HUGGINS: No, only this — it’s up to you! This is your big chance. Go in there and see how long you can last.

GEHRIG: Okay. But don’t hold your breath because I feel like I’m going to last a long time!”

Sources

The author adapted this article from his book Last Ride of the Iron Horse: How Lou Gehrig Battled ALS to Play One Final Championship Season (Sunbury Press, 2019). Descriptions of the game action come from box scores and play-by-play accounts on baseballreference.com and retrosheet.org.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA193805310.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1938/B05310NYA1938.htm

Photo credits: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 “Gehrig Plays 2000th Game as Yankees Win,” unbylined Associated Press article, Chicago Tribune, June 1, 1938.

2 James Dawson, “Gehrig, the ‘Iron Man’ of Baseball, Now Looks Ahead to 2,500 Games,” New York Times, June 1, 1938.

3 Ira Wolfert, North American Newspaper Alliance, September 20, 1941. The story of Eleanor urging Lou to end the streak at 1,999 was dramatized in the 1942 movie Pride of the Yankees and was recounted in her memoir, My Luke and I. I chose to cite this telling of Eleanor’s story because it seems to be the very first time it appeared in print.

4 Ray Robinson, Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig in His Time, 1990, p. 234.

5 The film clip of McCarthy addressing Gehrig can be found on the Getty Images website. It was used in a newsreel retrospective of Gehrig’s career, entitled “King of Diamonds,” released in 1952.

6 Lester Rodney, “2,005, Or How About a Week Off, Lou?” The Daily Worker, June 14, 1938.

7 Drew Middleton, “Lou Gehrig Plays 2,000th Straight,” Associated Press story, Kingsport (Tenn.) Times, June 1, 1938.

8 “Gehrig Plays 2000th Game as Yankees Win,” unbylined Associated Press article, Chicago Tribune, June 1, 1938.

9 “Gehrig’s 2000th Game Fails to Earn a Cheer,” New York Sun, June 1, 1938.

10 Script for the May 31, 1938, Believe It or Not. There are two known copies of the script, one signed by Ripley and Gehrig that sold for $4,700 in a 1999 auction, and one in the Doug and Hazel Anderson Storer Collection at the Wilson Library of the University of North Carolina. Doug Storer was a radio producer who worked on the Ripley program.

Additional Stats

New York Yankees 12

Boston Red Sox 5

Yankee Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.