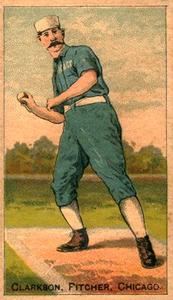

October 18, 1886: Chicago’s John Clarkson ‘calcimines’ the Browns in World Series opener

The 1886 Chicago White Stockings successfully defended their National League crown on the broad shoulders of captain Adrian “Cap” Anson, batting champ Mike “King” Kelly, and a dominant trio of pitchers. Between them, John Clarkson, Jim McCormick, and one-year wonder Jocko Flynn started and racked up a decision in every one of the team’s 124 games.

The 1886 Chicago White Stockings successfully defended their National League crown on the broad shoulders of captain Adrian “Cap” Anson, batting champ Mike “King” Kelly, and a dominant trio of pitchers. Between them, John Clarkson, Jim McCormick, and one-year wonder Jocko Flynn started and racked up a decision in every one of the team’s 124 games.

After spending much of the season in second place, Chicago took the NL lead for good in late August during a 14-game winning streak, kicked off by Clarkson’s one-hit shutout of the first-place Detroit Wolverines.1 Clarkson’s 36th win of the year, in the championship (regular) season finale, clinched the pennant and set up a rematch with the American Association champion St. Louis Browns in baseball’s third-ever postseason series between league champions – variously called the “world’s championship series,” “world series,” or “world’s series” in newspaper coverage.2

Officially, the previous year’s “world series” between the White Stockings and Browns had been a draw,3 but in reality, it was a train wreck brought on by poor planning.4 Pregame festivities delayed Game One so long it was halted by darkness after eight innings, deadlocked. Controversial calls by umpires – either uncertain or unscrupulous – triggered a Browns forfeit in Game Two and a near-riot in Game Four.5 Game Five in Pittsburgh drew little interest from fans (only 500 attended), and Game Six in Cincinnati drew little interest from its participants. (The teams committed 17 errors combined.)

The Series’ Game Seven finale6 was assumed to be a makeup for the earlier forfeit, until Chicago said it wasn’t – after losing it.7 The contest was so filled with errors, misplays, and lousy pitching that the Cincinnati Enquirer called it “one of the poorest games ever played [here].”8

Anson had planned to start Clarkson in Game Seven, but the 53-game winner was still asleep in his hotel room when the team left for the ballpark. He managed to get to the field just five minutes late, but when he got there, Anson told him, “You need not take off your coat, as you are not going to play.”9 A tired McCormick started in his place, with disastrous results.10

Neither side wanted the same in their 1886 rematch. Once it became clear that the two teams would repeat, Browns owner Chris Von der Ahe challenged White Stockings President Al Spalding to “a series of contests to be known as the world’s championship series,” and suggested “it would be better from a financial standpoint to play the entire series on the two home grounds.”11 The magnates agreed to a six-game series played in Chicago and then St. Louis, with a deciding seventh game, if needed, at a neutral site. They also agreed to randomly select each game’s umpire from a board of agreed-upon NL and AA arbiters, play by the rules of the home team’s league, and award all gate receipts to the team that won the Series.12

The rules now set, the Series was to open on Monday, October 18, in Chicago.

On the eve of the opening game, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported heavy betting at poolrooms in St. Louis, Chicago, and “other cities having a membership in either the League or American Association.” “Both teams are as evenly matched as any two clubs that ever faced each other on the diamond,” 13 the newspaper added, a sentiment matched by the odds-makers, as “all the wagers were made on an even-money-basis.”14

Shooting pool himself that day, Anson told one reporter, “We’re going to beat the Browns in these games just as sure as I’m going to make a point on this [shot]” – which he did. He assured his listener that “We will play the St. Louis Club on a square basis, and if we beat ’em, we beat ’em; if we don’t, we don’t, and that’s all there’s to it.”15

The Browns left St. Louis that night “full of confidence and beer,”16 after their four-game sweep of the NL Maroons in the St. Louis postseason city series.17 They arrived in Chicago the next morning accompanied by several hundred fans in Pullman cars “with banners floating and trumpets sounding.”18 They also brought with them the glass-enclosed, solid silver Wiman Trophy, emblematic of their American Association championship.19

A crowd estimated at 3,000 by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and 5,000 by the Chicago Tribune was entering West Side Park as the teams warmed up in a chill wind beneath a clearing sky.20 A decorative “Champions, 1886” was written in large lettering in front of each team’s bench, both foul lines, and behind the pitcher’s box. The home team entered behind a brass band, along with their mascot, young Willie Hahn, “dressed in the costume of the club.”21 Anson won the pregame toss and elected to have his White Stockings take the field first. The Association’s Jack McQuaid umpired.22

As expected, Clarkson strode to the pitching box, Chicago’s most reliable starter over the last three weeks of the season.23 Leading off for the Browns was their captain, Arlie Latham, despised by many Chicagoans for his incessant taunting of opposing players.24 He called for a high ball and after mostly bunting foul what the Chicago Inter-Ocean estimated at 20 pitches and the New York Times nine, struck out “amidst the most vociferous applause.”25

Pitching for the Browns was right-hander Dave Foutz, a two-way player who split time between the pitching box, first base, and the outfield. He’d quietly won a league-leading 41 games, with a league-low 2.11 ERA, and had been the winning pitcher in Game Seven of the 1885 World Series.

Foutz’s impressive résumé meant little to the White Stockings, who scored twice in their half of the first inning. Leadoff batter George Gore took a six-ball walk, then was forced at second on a grounder by Kelly. “Tricky Mike” stole second and came home on a triple by Anson over the right fielder’s head. An opposite-field single down the right-field line by cleanup hitter Fred Pfeffer plated Anson, giving Chicago a two-run lead.

Pfeffer was thrown out at second, though when is unclear. The Chicago Tribune wrote that he was gunned down trying to stretch his run-scoring single into a double, while the St. Louis Post-Dispatch said he made the out trying to swipe second base, two batters later.

A pair of Browns reached base in the second on a muffed third strike and a walk to fleet-footed Curt Welch, but a double play in between prevented a rally from developing. Over the next three innings, Clarkson retired the visitors in order, using his arsenal of overhand fastballs, side-arm drop curves, and changeups.26

Cross-gripping Yank Robinson collected the first hit for St. Louis leading off the sixth.27 Latham singled with two out, but Clarkson retired Bob Caruthers to end the threat.28 A standout two-way player, Caruthers, nicknamed Parisian Bob, won 30 games that year, and had the greatest offensive season for any nineteenth-century major-league pitcher. He hit .334 with 26 stolen bases, but even more impressively, led the American Association in on-base percentage (.448) and OPS (.974), with an eye-popping OPS+ of 201 (statistics compiled retroactively).

Despite having more traffic on the bases than Clarkson, Foutz also threw goose eggs in the middle innings. The Browns’ defense cracked in the sixth, gifting Anson’s lads a run on a passed ball and a Latham error after Pfeffer had singled leading off. Chicago led, 3-0.

Captain Charlie Comiskey collected the Browns’ second hit of the game in the seventh and advanced on an error by Gore but went no farther. Clarkson worked around a one-out triple to Robinson in the eighth, striking out light-hitting Doc Bushong and getting Latham to pop out to Anson at first base.

Chicago doubled its lead in the eighth. After Anson singled leading off, shortstop Bill Gleason fumbled a bunt from Pfeffer, putting runners on first and second.29 Big Ned Williamson, who’d set a new major-league single-season home-run record two years earlier,30 followed with a triple to center field, bringing both runners home. Second baseman Robinson threw wild trying to get Williamson at third, allowing him to score on the play as well.

In the top of the ninth, St. Louis tried in vain to avoid a whitewash. Caruthers reached on an error and Comiskey singled for his second hit of the day, but Clarkson squelched the comeback by fanning Welch. Clarkson had the first World Series win of his career, erasing a bit of the sting from how his previous postseason had ended.

The Chicago Daily News called the game “an overwhelming defeat for the Browns.”31 The Boston Globe said, “The Chicagos played in good form and fielded splendidly.”32 In the Chicago Inter-Ocean’s game story the next day, headlined “Coated with Calcimine,” the win was marked with a sonnet that mocked Browns fans and players alike, most notably Latham.33

The Browns were sanguine about the loss. Catcher Bushong offered that “the Chicagos never played a better game of ball in their lives.” “It was Clarkson who won the game.” “There was no batting him. He wouldn’t let us hit him, and he wouldn’t let us get more than a foot from the bases.”34 A cigar-smoking Robinson vowed to “get even some day.”35

“Der Prowns”36 would soon get even, and eventually win the Series, but on this chilly day in the Windy City, it was John Clarkson who basked in glory.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Stew Thornley and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Statscrew.com for pertinent information. He also relied on previews of the 1886 World Series and summaries of this game published in the Chicago Tribune, Chicago Inter-Ocean, Chicago Daily News, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and The Sporting News.

Notes

1 “The Sluggers Blanked,” Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1886: 2.

2 For example, the Chicago Tribune and The Sporting News referred to the “championship of the world series” in several stories describing the impending matches; The Sporting News used the shorter “World’s Series” as the title of its final series preview, published the morning of Game One, and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch applied the term “world series” in its summary of Game One. “A Challenge from the Browns,” Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1886: 10; “Spalding Is Willing,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1886: 1; “The Dates Selected,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1886: 1; Calumet, “The World’s Series,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1886: 1; “‘Doc’s’ Dictum,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 19, 1886: 7.

3 Major League Baseball recognizes each of the postseason championships between the National League and American Association champions, from 1884 through 1890, as World Series. The 1885 postseason championship series was the first to be explicitly identified in the press as a “world’s series.” World Series Summary, MLB World Series.com website, http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/postseason/mlb_ws.jsp?feature=index, accessed November 15, 2022; “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, October 20, 1885: 3.

4 See Paul E. Doutrich, “Champions, Tantrums and Bad Umps: The 1885 ‘World Series,’” Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2017, https://sabr.org/journal/article/champions-tantrums-and-bad-umps-the-1885-world-series/.

5 Bad calls in Game Four aggravated future evangelist Billy Sunday so profoundly that he “leaped off the Chicago bench with fist clenched and charged toward the umpire.” Doutrich, “Champions, Tantrums and Bad Umps: The 1885 ‘World Series.’”

6 The tour was initially planned as a set of 16 exhibition games in eight cities, with two contests each in St. Louis, Chicago, Philadelphia, Louisville, Baltimore, Cincinnati, Brooklyn, and New York. Browns owner Chris Von der Ahe and White Stockings President Al Spalding ultimately agreed to a less ambitious tour that dropped Brooklyn, New York, and Baltimore and added Pittsburgh. The Series was cut back to seven games after the Game Six debacle. “The Browns and the Chicagos,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 26, 1885: 3; “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 1, 1885: 8.

7 David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994), 104.

8 “World Beaters,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 25, 1885: 10.

9 “World Beaters.”

10 The Beer and Whisky League.

11 Von der Ahe’s challenge to Spalding was published in full in the Chicago Tribune and summarized in several other newspapers. “A Challenge from the Browns,” Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1886: 10.

12 Spalding and Von der Ahe separately elected to distribute half of the gate receipts to their ballplayers should they win the Series. “For the World’s Pennant,” Boston Globe, September 28, 1886: 1; Calumet, “The World’s Series,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1886: 1; “Anson’s Pets,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 18, 1886: 1.

13 “The Browns-Chicagos Series,” St. Louis Globe Democrat, October 17, 1886: 11.

14 “Even Money,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 18, 1886: 7.

15 Anson interestingly prefaced this remark by pointing out that his men were sober; a nod to Spalding’s ongoing battle to keep the White Stocking players from drinking to excess. The findings of a detective hired to follow players (including Anson) resulted in seven of them (but not Anson) being fined in July for drinking and keeping late hours. “Even Money,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 18, 1886: 7; Wendy Knickerbocker, “Billy Sunday,” SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/billy-sunday/.

16 “The Champions to Play,” Chicago Tribune, October 18, 1886: 2.

17 The Beer and Whisky League, 118; “Sporting,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 19, 1885: 6.

18 The St. Louis Globe-Democrat described one Pullman car as “tastefully decorated, long canvas streamers on each side of the outer panels bearing the legend, ‘St. Louis Browns – Champions 1886-87.’” “The Champions to Play”; “Sporting,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 18, 1886: 6.

19 The 26-inch-tall trophy “in the form of a batter at the plate” was put on display in the window of Spalding’s store on Chicago’s Madison Street “where it dazzles the eyes of the windy people who happen to pass by that way.” The trophy was created by New York Metropolitans owner Erastus Wiman as a goodwill gesture following his legal battle with the other Association club owners shortly after purchasing the franchise. The 1886 Browns were the first team to receive the trophy and the only Association champion to publicly display it. Bill Lamb, Erastus Wiman SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/erastus-wiman/; “’Doc’s’ Dictum,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 19, 1886: 7.

20 Newspapers reporting on the game varied in their description of how unpleasant the weather was. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch said fans’ “teeth were chattering with cold and their lips blue from the strong wind directly in their faces the game through.” “‘Doc’s’ Dictum.”

21 A resident of the neighborhood adjoining West Side Park, the youngster first began serving as the team mascot the previous season. At first no taller than the length of a bat, he was variously reported to be 5 to 9 years old. The Cincinnati Enquirer was so amused with reports of his age that they referred to him as Chicago’s “one-hundred-and-twenty-nine-year-old mascotte.” “Big Base Ball,” Decatur (Illinois) Daily Republican, October 1, 1885: 2; “Around Town,” Deadwood (South Dakota) Pioneer Times, October 11, 1885: 3; “Base-Ball Notes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 21, 1886: 10; “Chicago Against Detroit,” Freeport (Illinois) Journal, June 21, 1886: 1; John Thorn, “Some Superstitions of the Year 1886,” October 20, 2015, Our Game website, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/some-superstitions-of-the-year-1886-9af42bafcf71, accessed October 17, 2022; “Anson’s Pets.”

22 McQuaid’s name was invariably spelled McQuade in contemporary accounts of the game. The magnates also agreed to implement in Game Two a novel umpiring scheme proposed by Spalding’s brother, J.W. Spalding. The co-founder of A.G. Spalding and Bros., Inc. proposed “elevating the position of the umpire” by having him serve solely to referee the decisions of two other umpires, one selected by each team. One of the team-selected umpires would call balls and strikes and plays at the plate, with the other making calls at the other bases. The referee would hear challenges to umpire calls from an “aggrieved party” and make a final ruling. “The Browns-Chicagos Series”; “Brokers’s Book Tells Spalding Story,” Golfdom, April 1964: 64, https://archive.lib.msu.edu/tic/golfd/article/1946apr64.pdf, accessed October 16, 2022.

23 Between September 18 and the season finale on October 9, Clarkson had a 5-2-1 record versus 2-3 for Flynn and 1-4 for McCormick.

24 For example, on the morning of Game One, Latham was referred to by the Chicago Tribune as “the monkey that covers third base for the Browns.” Two years later Latham’s habit earned him the nickname “The Freshest Man on Earth,” from a popular song of the same name. “The Champions to Play,” Chicago Tribune, October 18, 1886: 2; “Straight Hits,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 8, 1888: 7.

25 “Coated with Calcimine,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, October 19, 1886: 3; “The Browns Whitewashed,” New York Times, October 19, 1886: 9; “Anson’s Pets.”

26 Mike Bojanowski, “The Top 100 Cubs of All Time – #20 John Clarkson,” January 30, 2007, SB Nation website, https://www.bleedcubbieblue.com/2007/1/30/91847/7000, accessed October 16, 2022.

27 Chris Rainey, Yank Robinson SABR bio, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Yank-Robinson/.

28 Caruthers had been injured several days earlier, in the first game of the St. Louis city series, causing considerable concern among Browns fans that he might not recover in time to play in this game. “Sporting,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 18, 1886; The Beer and Whisky League, 118.

29 The Sporting News identified second baseman Robinson as making the error on Pfeffer’s bunt, but all other detailed game summaries attribute the error to the Browns shortstop, Gleason. “The Great Games,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1886: 2.

30 Williamson was listed at 221 pounds a month before the start of the season. His record of 27 home runs hit in 1884 stood for 35 years, until Babe Ruth hit 29 for the 1919 Boston Red Sox. “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, March 31, 1886: 3.

31 “A Victory for the Chicagos,” Chicago Daily News, October 19, 1886: 1.

32 “A Big Game at Chicago,” Boston Globe, October 19, 1886: 5.

33 “Coated with Calcimine.” The sonnet was as follows:

St. Louis came down like a wolf on the fold,

And their pockets were filled up with greenbacks and gold.

They told us great tales, amid smiles and frowns;

They bet all their greenbacks, and swore by their Browns;

But a basket of goose-eggs they got for their share,

For Williamson, Kelly and Anson were there.

Three-baggers, two-baggers, and Latham, take care;

For the Browns may play ball in a country town well,

But the Kings of the League you’ll find, Latham, are – well.

34 Bushong also revealingly said about Clarkson that “he won it by pitching in a way that he seldom does.” This implies that Clarkson had modified his pitching motion and/or pitch selection/velocity/location. No other newspaper account of the game mentions Clarkson pitching any differently than in the past, suggesting that what he did was so subtle that only a ballplayer (and maybe only an experienced catcher) would have noticed. “‘Doc’s’ Dictum.”

35 “‘Doc’s’ Dictum.”

36 “Der Prowns” was how Von der Ahe commonly referred to his team in his thick German accent. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat was so certain that the Browns would triumph in the Series that they printed a line under the masthead counting down the number of days until they “beat the Chicagos.” See, for example, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 19, 1886: 6.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Stockings 6

St. Louis Browns 0

Game 1, World Series

West Side Park

Chicago, IL

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.