October 5, 1935: Defense dooms Cubs in Game 4

With the Detroit Tigers seizing a two-games-to-one lead in the 1935 World Series on the Chicago Cubs after a wild extra-inning affair in Game Three, managers Charlie Grimm and Mickey Cochrane were compelled to shuffle their lineups. “The two managers, reckless in their manipulation of talent in the turbulent concluding innings, forced themselves into a new setup for the fourth of the series today,” wrote Irving Vaughan of the Chicago Tribune in previewing the day’s contest.1

With the Detroit Tigers seizing a two-games-to-one lead in the 1935 World Series on the Chicago Cubs after a wild extra-inning affair in Game Three, managers Charlie Grimm and Mickey Cochrane were compelled to shuffle their lineups. “The two managers, reckless in their manipulation of talent in the turbulent concluding innings, forced themselves into a new setup for the fourth of the series today,” wrote Irving Vaughan of the Chicago Tribune in previewing the day’s contest.1

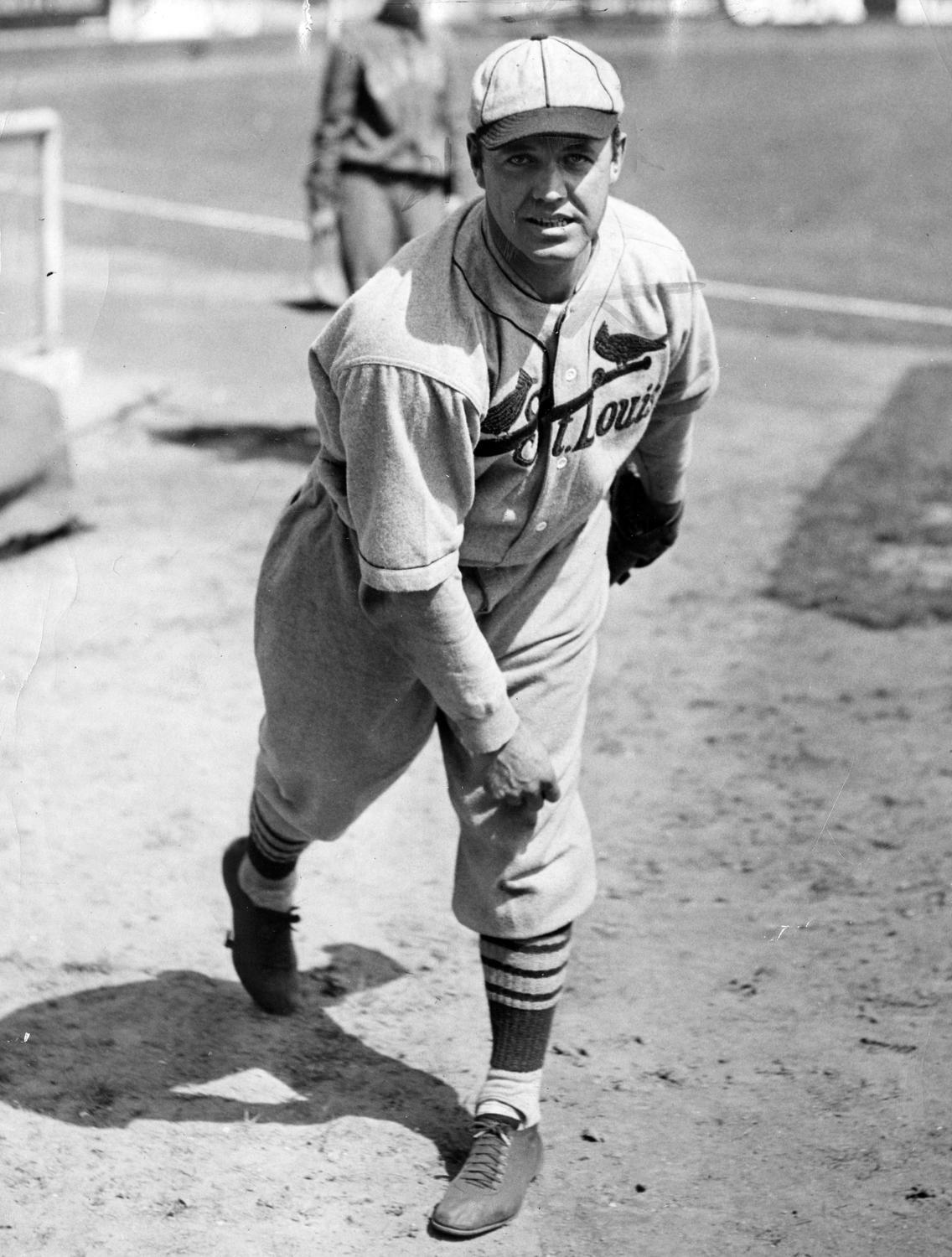

The fourth game pitted two veteran pitchers who had yet to prove themselves capable of World Series success. Grimm handed the ball to Tex Carleton, a winner 11 times during the regular season but who had appeared only once during the Cubs’ incredible 21-game winning streak in September. Carleton had also faced the Tigers in Game Four of the 1934 fall classic while a member of the St. Louis Cardinals, but he was pulled in the third inning by Cardinals skipper Frankie Frisch while permitting three runs as part of a 10-4 thrashing by Detroit. The following afternoon, Carleton relieved Dizzy Dean as the Cardinals lost again in Game Five.

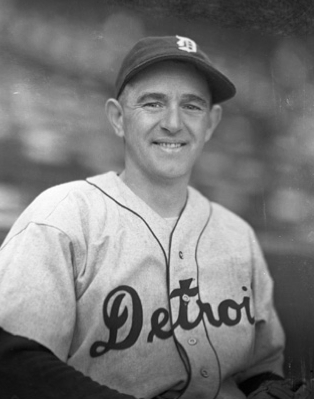

Cochrane, meanwhile, was turning to General Crowder. Crowder himself had appeared twice in the 1934 Series — including a loss in Game One against Dean, when Cochrane infamously had let word leak that he did not want to waste his own number-one starter, Schoolboy Rowe, against the St. Louis ace. Crowder had been on the losing end of the 1933 World Series as well while pitching for the Washington Senators, dropping Game Two to Hal Schumacher.

During batting practice, Rowe — victorious in relief the previous day in Game Three — had been greeted with angry booing from those in Wrigley’s outfield stands. The jeers from the ancestors of the future “Bleacher Bums” turned into cheers, however, when Rowe launched a total of nine baseballs into the seats as souvenirs.

As part of Cochrane’s makeshift order, he was forced to do without his slugging first baseman, Hank Greenberg, for the second straight day as Marv Owen once again moved over from third base while Flea Clifton took Owen’s spot at the hot corner.

Would this be the day that either Carleton or Crowder would finally shine in postseason play?

Both men were determined to make it so. But while each would pitch well, Crowder made an additional statement with his bat while the normally surehanded Chicago defense abandoned Carleton.

The Cubs starter escaped trouble early, enduring a flurry of Detroit baserunners but permitting only a lone run. This included a particularly perilous second inning in which shortstop Bill Jurges made a leaping snag of a Clifton liner with the bases loaded, “going into the air like a man springs,” wrote Charles Ward of the Detroit Free Press – spearing a ball and turning it into an inning-ending double play by throwing to Billy Herman at second to catch Pete Fox off the bag.2

Gabby Hartnett followed in the bottom half by leading off the Cubs’ turn with a home run, staking Carleton to 1-0 lead. The advantage was short-lived, however, as in the Tigers third, star second baseman Charlie Gehringer doubled home Crowder (who had led off with a single) to tie the game.

The two pitchers of past World Series misfortune were not about to let another opportunity slip away. Each shut down the opponents’ bats time after time; but the difference in the game came from misplays by the Chicago gloves in the Tigers’ sixth. “The assembled multitude saw Augie Galan let a fly ball trickle through his hands after he had set himself to make the catch,” wrote Vaughan. Clifton, hustling all the way, made it into second, and scored on the next play with Crowder batting. “A moment later they saw Bill Jurges stage a sandlot error on the easiest sort of roller … who reached down nonchalantly for the ball, but it wasn’t there.”3 An unnerved Carleton then balked Crowder to second, but was able to end the malaise with no further damage.

The Cubs appeared to be staging a rally in the bottom half, but Crowder got revenge for Hartnett’s homer as he fanned the Cubs catcher with the tying run on third and one out, followed by Frank Demaree popping out to Gehringer to end the inning.

Going the distance, Crowder had permitted only three Cubs hits until the ninth, when Demaree and Phil Cavarretta each hit the first pitch for singles after Hartnett opened the inning by hitting a screaming liner to Bill Rogell at short. But Rogell took care of the final two outs as well, turning a double play on a tapper off the bat of Stan Hack by flipping to Gehringer, who fired on to Owen to end the game. “(Crowder) made it easy for his fielders, also for himself, by refusing to let the Cubs get hold of anything with their bats,” an impressed Vaughan continued. “Except for the five hits, only one ball was driven to an outfielder.”4 The effort was nearly wasted by Cochrane’s men, however, as the Tigers left 13 runners on base with Carleton and reliever Charlie Root (who entered in the eighth) able to keep any further runners from crossing the plate.

Like Vaughan, the Detroit writer Ward had been equally moved by Crowder’s performance: “He grinned wearily and trudged off the field with his tired, slow-footed gait, happy in the thought that he had proved that he could do what everybody had said he couldn’t do — pitch winning ball in a World Series.”5

Cochrane, the veteran of so many October battles, claimed to have never seen a finer effort. “This was a game we had to win, and the General knew it,” the manager said. “In my opinion, it was one of the smartest games I’ve ever seen a pitcher work.”6 But the greatest source of inspiration for Crowder had come from his wife, who was bedridden back at their home in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for the past several months with a serious but undisclosed illness. “I’ve just prayed that boy would win one game — one game in the World Series,” a grateful Mrs. Crowder said. “For three years, that’s all I’ve been living for.”7

As for the Cubs, the spirit of their amazing streak to end the regular season seemed to be burning out. “A crowd of 49,350 draped itself around the Wrigley Field arena to see the Cubs finally lose the glamour with which they adorned themselves in their spectacular September pennant drive,” Vaughan wrote in conclusion.8

With no offdays scheduled during the Series, the Tigers would attempt to wrap up the 1935 crown the following afternoon in Game Five at Wrigley.

This article appears in “Wrigley Field: The Friendly Confines at Clark and Addison” (SABR, 2019), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more stories from this book online, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHN/CHN193510050.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1935/B10050CHN1935.htm

Notes

1 Irving Vaughan, “Cubs Lose, 6-5; Use Carleton Today,” Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1935.

2 Charles Ward, “Crowder Gives Tigers 2-Game Lead,” Detroit Free Press, October 6, 1935.

3 Vaughan.

4 Ibid.

5 Ward.

6 Grantland Rice, “Spring Promise,” New York Herald Tribune, October 6, 1935.

7 Doug Feldmann, September Streak: The 1935 Chicago Cubs Chase the Pennant (Jefferson, North Caolina: McFarland, 2002), 199.

8 Vaughan.

Additional Stats

Detroit Tigers 2

Chicago Cubs 1

Game 4, WS

Wrigley Field

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.