September 15, 1884: White Stockings outshine Eclipse at Louisville’s ‘lit’ Southern Exposition

The social calendars for many a Louisvillian in the mid-1880s were anchored by two annual marquee events: the Kentucky Derby and the Southern Exposition. The Derby, which grew to become the signature event in American horse racing, was held on the first Friday in May at Churchill Downs.1 The Southern Exposition was a regional fair held annually from 1883 to 1887, showcasing local goods and marvels of the Gilded Age.

The social calendars for many a Louisvillian in the mid-1880s were anchored by two annual marquee events: the Kentucky Derby and the Southern Exposition. The Derby, which grew to become the signature event in American horse racing, was held on the first Friday in May at Churchill Downs.1 The Southern Exposition was a regional fair held annually from 1883 to 1887, showcasing local goods and marvels of the Gilded Age.

One of the key attractions at the 1884 Southern Exposition was a mid-September interleague exhibition game between the National League’s Chicago White Stockings and the American Association’s Louisville Eclipse. The game was played before what may have been the largest crowd to attend a “base ball match” in nearly two decades.

As described by its organizing committee, the Southern Exposition served “to exhibit the products and resources of the Southern states to Northern and Eastern manufacturers and the implements and machines of the great industries of the former.”2 The centerpiece of the Exposition was a 900-foot-long, 600-foot-wide exhibit hall, built along with several smaller buildings on 45 acres of land adjacent to Louisville’s Central Park. The interior of the exhibit hall and building exteriors throughout the exposition grounds were illuminated with a combination of 75 arc lights and 46,000 incandescent light bulbs, the latter manufactured by the Edison Electric Light Company and installed under the supervision of Thomas Edison himself.3 The lighting allowed for evening attendance throughout the exposition grounds, a first for such a large venue. At its debut, the Southern Exposition boasted more electric lights than all of New York City.4

Officially opened by President Chester A. Arthur on August 1, 1883, the Exposition welcomed 971,000 visitors over 100 days.5 Envisioned at first as a one-time event, the Exposition proved so profitable that it was held again in 1884, with a number of changes. At the center of the Exposition building, Edison workmen installed a 35-foot-tall water fountain illuminated by dozens of colored light bulbs, a dazzling sight known as an “electric fountain.”6 Also, to the south of the hall, a three-sided amphitheater with covered seating for 15,0007 was constructed surrounding a large parade ground. There, on Monday, September 15, Chicago’s Whites and the hometown Eclipse would be on display.

An amateur club when formed in the 1850s,8 the Eclipse evolved into a professional nine that was a charter member of the American Association when it debuted in 1882.9 Louisville sat in third place as Chicago came to town, five games behind the first place New York Metropolitans, with 20 games remaining in their quest for their first Association crown.

The White Stockings, NL champions from 1880 to 1882, were out of contention for the 1884 pennant, 24½ games behind the front-running Providence Grays. Coming off an Eastern swing through New York and Philadelphia, they were on their way back to the friendly confines of Lake Front Park. A change in Lake Front ground rules for the 1884 season gave batters a home run instead of a double for balls hit over the short porch in right field, only180 feet from home plate. That enabled Chicago to launch a major-league record 142 home runs by year’s end.10

Leading up to the game, the Louisville Courier-Journal shared one anonymous Kentuckian’s opinion that “the Louisvilles are the equals of any club in America.”11 The newspaper predicted that the game would feature “the attendance of a larger number of ladies than were ever seen at a base ball game in Louisville.”12 The morning of the game, the Courier-Journal offered yet another enticement to see Eclipse battle the “Chicago League Champions.” The exposition entrance fee, which included admission to the “immense amphitheater,” was only 25 cents, half the usual charge.13

Crowds began arriving at 1:30 P.M., two hours before game time. Once the amphitheater was filled, spectators “continued to pour into the grounds until every available foot of space around the guard ropes on all sides was occupied.”14 The Courier-Journal declared that “such a mass of enthusiastic spectators was never seen in the West.”15 Sporting Life estimated the crowd at 20,000 and called it the largest ever assembled on a Louisville ball ground.16 The Chicago Tribune agreed that no bigger crowd had witnessed a ballgame in Louisville, yet declared that only 2,500 attended.17 The Cincinnati Enquirer put the crowd size at 22,000, minimum.18

A crowd of this size for a game of base ball hadn’t been reported by any newspaper19 since the aborted opening game of the 1866 national championship series between the Athletics of Philadelphia and the Atlantics of Brooklyn. During the first inning of that contest, many of the reported 30,000 spectators spilled onto the field and couldn’t be persuaded to give players enough room for the game to go on.20

While newspaper reporting of ballgame attendance figures in the nineteenth century was spotty, nearly a dozen games between the 1866 national championship and this one were described as played before crowds of “up to 20,000,” “20,000,” or “20,000 or more.” A list that includes the June 1870 match at Brooklyn’s Capitoline Grounds when the undefeated Cincinnati Reds fell to the Atlantics, the first-ever National League championship (regular) season match between the Boston Red Stockings and Chicago White Stockings in 1876, and the inaugural game at the original Polo Grounds in 1880.21

A decade before the Southern Exposition, 20,000 had also gathered to see the White Stockings take on the Philadelphia Whites in an exhibition close by another large fair, the St. Louis Exposition of 1874. But that game never happened, as Philadelphia backed out, unwilling to make the trip.22 This time, with an opportunity to show hometown fans they could compete with the former NL standard-bearers, Chicago’s opponent would have no travel issues.

One member of the Eclipse, though, likely saw the exhibition game as an opportunity lost: Joe Gerhardt, the club’s second baseman. The team’s manager one year earlier, Gerhardt was entitled to a one-third share of the receipts from the saloon at its home ballpark, Eclipse Park. Gerhardt had exacted the lucrative deal from his replacement, Mike Walsh, during preseason contract negotiations, as an enticement to stay with Louisville in the face of an Association-stipulated $1,800 maximum salary.23 At home games, Gerhardt frequently worked behind the counter in between innings, boosting his earnings while personally serving “a horde of wide-eyed hero worshippers with their drinks.” He wouldn’t be doing that at the Exposition.24

Despite its spacious design, the grounds, according to the Courier-Journal, “were no means good.”25 In the middle stood a 125-foot-tall open framework iron tower that held ten 2,000-candlepower electric arc lights to illuminate the parade grounds for nighttime events.26 No mention is made of any spectators spilling onto the field in order to see the game, as occasionally happened for well-attended games in the nineteenth century – a benefit of playing this game on a vast parade ground.

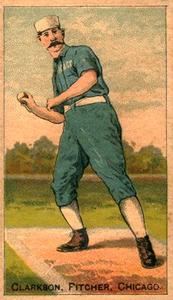

Louisville took the field with its regular pitcher, and the Association’s most dominant hurler, eventual 52-game winner Guy Hecker. Chicago captain Cap Anson elected to start his number-three pitcher, slender (5-feet-10, 155 pounds) John Clarkson on his way to a 10-win season.27

The crowd was enthusiastic from the start, with applause that went around the grounds “to thrilling effect.”28 The play was sloppy at times, particularly on the part of the visiting White Stockings, who “fielded like a lot of school-boys,” committing 10 errors.29 This was no surprise; unlike Louisville, which boasted the highest fielding percentage of any Association team in 1884, Chicago topped the NL in errors that season, with 595 or 5.3 per game. Chicago persevered, winning 11-7, on the strength of home runs by Anson, Clarkson, leadoff batter Abner Dalrymple, and NL batting champ-to-be King Kelly.

Typically Chicago’s right fielder in 1884, Kelly spent this game shuttling around the diamond. After starting in right field, he replaced catcher Silver Flint when Flint got sick in the middle of the game. (As Flint was being tended to, Chicago infielders Ned Williamson and Fred Pfeffer gave the crowd an impromptu throwing exhibition; each heaving a ball over the top of the iron light tower.30) When play resumed, Kelly split a finger catching Clarkson’s first pitch to him, and had to switch places with Anson, who’d been manning first base.

Louisville mustered only three hits off Clarkson, who, as hinted in the Courier-Journal, delivered the ball with his arm above the shoulder, a pitching motion allowed in the NL but banned by the AA.31 A pair of light-hitting Eclipse regulars each registered a rare extra-base hit. Catcher Dan Sullivan, who compiled an anemic .233/.262./.289 slash line across a five-year career, doubled, and shortstop Tom McLaughlin, who hit only two regular-season home runs in his five years in the big leagues, clubbed a bottom-of-the-ninth three-run homer. Former NL batting champ Pete Browning, the Louisville slugger who legend holds broke out of a batting slump earlier in the season after using a custom bat turned for him by 17-year-old apprentice Bud Hillerich, found no hits in the model he used for this game; he went 0-for-5.

Long before the game ended, the size of the crowd shrank noticeably. Once defeat seemed certain for Eclipse, many departed in order to get a seat at an evening concert in the Exposition’s music hall.

Two years passed before a larger crowd witnessed a game of base ball; not on a parade ground, but on a former polo field, in New York City.32

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Stew Thornley and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Bryan S. Bush, Louisville’s Southern Exposition, 1883-1887 (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2011), Bob Bailey’s SABR biography of Eclipse Park, and Philip Von Borries’ SABR biography of Pete Browning. He also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for pertinent information.

Notes

1 Not until 1931 was the Derby contested on the first Saturday in May, as it has been ever since. The winner of the 1884 renewal, Buchanan, was ridden by Isaac Murphy, a Black man born into slavery who was a member of the inaugural class of jockeys inducted into the National Racing Hall of Fame in 1955.

2 Bryan S. Bush, Louisville’s Southern Exposition, 1883-1887, 22.

3 “Exposition Light,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 3, 1883: 6.

4 Susan Page Davis, “The Southern Exposition 1883-1887,” Heroes, Heroines and History website, August 23, 2013, https://www.hhhistory.com/2013/08/the-southern-exposition-1883-1887.html.

5 Louisville’s Southern Exposition, 1883-1887, 50.

6 Two years later, an electric fountain provided by a British engineer was installed as a centerpiece of the new St. George Grounds on Staten Island, New York, the final home of the American Association New York Metropolitans. “Fairyland on Staten Island,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 17, 1886: 348.

7 “No Fireworks,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 22, 1884: 6.

8 “Another Base Ball Club,” Louisville Daily Journal, August 20, 1858: 3.

9 Illustrating the long-standing significance of horse racing to the city of Louisville, the name Eclipse came not from the awe-inspiring alignment of celestial bodies but from a legendary eighteenth-century racehorse of the same name. The legacy of Eclipse continues to be prominent outside the world of horse racing into the twenty-first century; Mitsubishi Motors’ Eclipse sport sedan, manufactured from 1989 through 2011, was, like the American Association nine, named after the racehorse.

10 Chicago’s record was not broken until the 1927 New York Yankees of Murderer’s Row fame. The average number of home runs hit per game at Lake Front Park during the 1884 season (3.52) remains a major-league record.

11 “A Great Club,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 13, 1884: 5.

12 “Amusements,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 14, 1884: 3; “The News,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 15, 1884: 1.

13 “Twenty-Five Cent Day at the Exposition,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 15, 1884: 8; “Today’s Attractions,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 15, 1884: 8.

14 “Base Ball at the Ex,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 16, 1884: 5.

15 “Base Ball at the Ex.” This claim trumped one made two weeks earlier by the Courier-Journal, when it called the crowd on hand for a military drill competition held on the parade ground “the largest outdoor audience ever assembled in the West.” That competition was capped off by an evening fireworks display, accompanied by music from Cappa’s Seventh Regiment band, the same band that under the direction of John Philip Sousa, later played the “Star-Spangled Banner” at the April 1923 opening of the original Yankee Stadium. “The Biggest Yet,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 29, 1884: 6.

16 “Two Noteworthy Games,” Sporting Life, September 24, 1884: 2.

17 “Chicago, 11; Louisville, 7,” Chicago Tribune, September 16, 1884: 3.

18 “Twenty-two Thousand People Present,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 16, 1884: 2. On September 17, the Indianapolis News mentioned that 22,000 had attended a game in Louisville (presumably this one), calling the large crowd “testimony to the love of out door sport as positive as any that the English ever gave.” “Current Comment,” Indianapolis News, September 17, 1884: 2.

19 Based on the author’s review of multiple newspaper archives, including those of the New York Clipper, Sporting Life, newspapers.com, and genealogy.com. The author did find a letter to the editor in the Boston Watchman and Redeemer, dated August 2, 1871, in which a Chicagoan claimed 25,000 witnessed a recent game in that city, a crowd the letter-writer said “daily papers” estimated at 30,000. The letter-writer was almost certainly referring to a National Association contest between the White Stockings and the Mutuals played at Lake Front Park on July 28, which both the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Republican described as played before a crowd that was unusually large. Those publications estimated attendance was only 12,000 or 11,000, respectively. J.C., “Chicago Correspondence,” Boston Watchman and Reflector, August 10, 1871: 6; “White Stockings vs. Mutuals,” Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1871: 4; “Top of the Heap,” Chicago Republican, July 29, 1871: 4.

20 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 2, 1866: 4.

21 Based on the author’s review. The full list of games identified by the author in which one or more newspapers reported attendance of “up to 20,000,” “20,000,” or “more than 20,000” follows. Not included in this list is an unspecified game referenced in a widely published critique of baseball fanatics dated May 8, 1876, in which the writer referred to attending a game with 20,000 “more or less demented” and “feeble-minded” spectators. “Making the Home Base,” Pittsburgh Gazette, May 31, 1876: 2.

|

Date |

Location |

Visitor |

Home Team |

Reference(s) |

|

August 31, 1868 |

Athletic Grounds, Philadelphia |

Atlantics |

Athletics |

“Base Ball,” Portland (Maine) Press, September 1, 1868: 3. |

|

June 21, 1869 |

Athletic Grounds, Philadelphia |

Cincinnati Reds |

Athletics |

“Philadelphia,” Bedford (Pennsylvania) Gazette, July 2, 1869: 2. |

|

July 4, 1869 |

Capitoline Grounds, Brooklyn |

Athletics |

Atlantics |

“Charley Fulmer,” New York Clipper, January 22, 1887: 713. Contemporary accounts put the crowd at 15,000. |

|

June 13, 1870 |

Union Grounds, Brooklyn |

Cincinnati Reds |

Mutuals |

“Telegraphic Summary,” Baltimore Sun, June 14, 1870: 1; “Base Ball,” Washington Morning Chronicle, June 14, 1870: 1. |

|

June 14, 1870 |

Capitoline Grounds, Brooklyn |

Cincinnati Reds |

Atlantics |

“The Cincinnati Club in the Metropolis,” New York Clipper, June 25, 1870: 92; “The Tour of the Red Stockings,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 15, 1870: 4. |

|

June 22, 1870 |

Athletic Grounds, Philadelphia |

Cincinnati Reds |

Athletics |

“Great Base Ball Excitement – Athletics vs. Red Stockings,” Pittsburgh Gazette, June 23, 1870: 1; “The Tour of the Red Stockings,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 23, 1870: 8. |

|

July 4, 1870 |

Capitoline Grounds, Brooklyn |

Chicago White Stockings |

Atlantics |

“The National Game,” Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1870: 4. |

|

October 3, 1873 |

Union Grounds, Brooklyn |

Boston Red Stockings (NA) |

Atlantics (NA) |

“Base Ball,” Boston Globe, October 3, 1873: 1. |

|

May 30, 1876 |

South End Grounds, Boston |

Chicago White Stockings (NL) |

Boston Reds (NL) |

“White Stockings vs. Boston,” Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1876: 8; “Chicagos,” Fall River Evening News, June 3, 1876: 2. Tribune headline said 20,000 but story implies only 15,000. |

|

September 29, 1880 |

Polo Grounds, New York |

Washington Nationals (NL) |

New York Metropolitans |

“Metropolitans 4; Nationals, 2,” Boston Globe, September 30, 1880: 3. |

|

September 10, 1882 |

Sportsman’s Park, St. Louis |

Cincinnati (AA) |

St. Louis Browns (AA) |

“Cincinnati 9 – St. Louis 1,” Cincinnati Commercial, September 11, 1882: 8. |

|

May 13, 1884 |

Washington Park, Brooklyn |

Baltimore Orioles (AA) |

Brooklyn (AA) |

“Baltimore Beaten by Brooklyn,” Indianapolis Journal, May 14, 1884: 2; “Base Ball,” Indianapolis News, May 14, 1884: 3. |

|

May 15, 1884 |

Washington Park, Brooklyn |

Baltimore Orioles (AA) |

Brooklyn (AA) |

“A Redeemed Pitcher,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 16, 1884: 3. |

|

May 30, 1884 (game 2) |

South End Grounds, Boston |

New York Giants (NL) |

Boston Red Stockings (NL) |

“Won One, Lost One,” Boston Journal, May 31, 1884: 2. |

22 Chicago and Philadelphia had reportedly agreed to travel to St. Louis during an offday in the middle of a two-game National Association championship season series between the two teams in Chicago. The day after the postponed St. Louis match, the two teams held an exhibition in Chicago to mark the third anniversary of that city’s Great Fire. “Base Ball,” St. Louis Republican, October 9, 1874: 4; “Whites and Philadelphias,” Chicago Tribune, October 10, 1874: 12.

23 John J. McCloskey,” Gerhardt’s ’84 Salary Was $1,800 and Third of Bar Receipts,” Louisville Courier-Journal, February 4, 1934: 35. Modern databases, as well as several contemporary sources, identify Walsh as the Eclipse manager during the 1884 season, but multiple accounts assert that Gerhardt handled manager responsibilities that season. An umpire before he assumed Louisville managerial responsibilities in 1883, Walsh has been called the first salaried umpire in major-league history. “Picked Up,” Louisville Courier-Journal, March 4, 1884: 8; “Notes,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 13, 1884: 5; Tommy Fitzgerald, “Louisville Started Umpires and Bats,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 24, 1939: 51.

24 “Gerhardt’s ’84 Salary Was $1,800 and Third of Bar Receipts.” On game day at the Southern Exposition, Gerhardt was likely grieving a loss far greater than what he might have earned had the game been played at Eclipse Park; five weeks earlier his infant son had died of cholera. “Deaths,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 7, 1884: 5.

25 “Base Ball at the Ex.”

26 Louisville’s Southern Exposition, 1883-1887, 56; “Exposition Affairs,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 8, 1884: 8.

27 A year later Clarkson would collect 53 wins as Anson’s ace. Only Old Hoss Radbourn of the 1884 Providence Grays ever topped that total in a single major-league season.

28 “Base Ball at the Ex.”

29 “Base Ball at the Ex.”

30 “Notes,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 16, 1884: 5.

31 “Notes.” Hecker presumably followed the American Association rule, which required that pitches “pass below the line of [the pitcher’s] shoulder.” “The American Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 23, 1882: 645.

32 The next game identified by the author with reported attendance of over 22,000 was the second game of a May 31, 1886, doubleheader at the original Polo Grounds. Officially listed as having an attendance of 26,000, contemporary accounts claimed as many as 31,000 were there. “The Polo Grounds Packed,” New York Sun, June 1, 1886: 3; “No Room for the Players,” New York Tribune, June 1, 1886: 8; “Winning Even Honors,” New York Times, June 1, 1886: 2.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Stockings 11

Louisville Eclipse 7

Southern Exposition Parade Ground

Louisville, KY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.