September 18, 1963: Mets lose to Phillies in their second ‘Last Game’ at the Polo Grounds

The Polo Grounds had been an important part of the New York sports scene since its original use in the nineteenth century as a field for polo players and then, in several different incarnations, as a home for professional baseball. The park “opened for baseball use September 29, 1880”1 and over the years a number of different New York-based ballparks called “the Polo Grounds” served as the setting for important baseball “final games,” including the last game played at the Polo Grounds by the New York Mets.

The Polo Grounds had been an important part of the New York sports scene since its original use in the nineteenth century as a field for polo players and then, in several different incarnations, as a home for professional baseball. The park “opened for baseball use September 29, 1880”1 and over the years a number of different New York-based ballparks called “the Polo Grounds” served as the setting for important baseball “final games,” including the last game played at the Polo Grounds by the New York Mets.

Before the Mets’ final game in this ballpark, other famous valedictory games had been played at the Polo Grounds too. For instance, the Giants played their last game in this ballpark on September 29, 1957. Sportswriter Red Smith described what happened after the Giants’ final game: “Clawing with fingernails and pen knives, the fans dug up home plate and the pitcher’s rubber. They even pried loose the plaque on the Eddie Grant Memorial in center field. Massed in deep center at the foot of the club house steps, the crowds sang ‘Auld Lang Syne,’ shouted for favorite players and yelled abuse at Horace Stoneham.”2

At the time, New Yorkers did not know that another baseball team would be formed and need a place to play. When the New York Mets took to the field in 1962, at first they did so at the Polo Grounds, which Smith described as that “grimy old slum beside the Harlem [River],” because they didn’t have their own ballpark.3 At the end of their first season, the Mets planned to bid goodbye to the Polo Grounds and use the field at Shea Stadium, their new home in Flushing, when the 1963 season arrived.

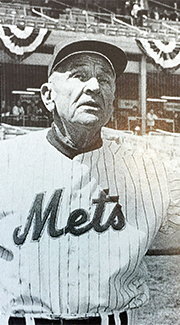

The Mets won the last home game of their inaugural season — a 2-1 victory over the Cubs on September 23, 1962 — in what they thought would be their last game at the Polo Grounds. Manager Casey Stengel “stood at the plate and gabbed into a microphone. Fans couldn’t hear his words but they applauded when he was done and [he] responded with a bow and then a jig. It was a comic leave taking with no sweet sorrow.”4

When construction on Shea Stadium was not yet complete at the start of the 1963 season, the Mets returned to the Polo Grounds for another season and thus, unexpectedly, marked a second final game there. Gordon White of the New York Times wrote: “There wasn’t too much fuss and bother about the affair. The quiet gathering seemed more akin to a crowd at spring training — there appeared to be more persons running around on the field than in the stands.”5

Before the game Stengel entertained the crowds and reporters who recalled “the good old days beneath Coogan’s Bluff.” After finishing filming a promotional film for the Mets, he said, “Didn’t you see me out there with those movie and newsreel guys? Why I was so choked up that I couldn’t stop crying. The place has its memories.”6

“A disappointing crowd of 1,752 mourners came to the wake on a dismal day with nary a Let’s Go Mets banner fluttering in the stands.”7 In the season leading up to this final game at the Polo Grounds, the Mets had improved their record from 1962 but it still seemed likely that they could finish their second season with fewer than 50 wins. They had a 49-102 record heading into their series with the Philadelphia Phillies.

The Mets’ opponents for their final game at the Polo Grounds were not in a nostalgic mood. Going into their two-game series against the Mets, the Phillies were tied for fourth place in the National League, 13 games behind the Los Angeles Dodgers. Although they had no chance to make the postseason, they were playing for money, since the first four teams in each league “share in the World Series loot” and the Phillies wanted to grab as much of it as they could.8 The Phillies won the first game, 8-6, and were hoping for a sweep before heading west, where they would finish their season against the Dodgers and the Giants, two of the best teams in the league.

Craig Anderson took the mound for the Mets. After a poor 1962 season with the Mets, the right-hander spent the season with their Triple-A team in Buffalo before being called up in September. Anderson had lost 16 times since recording his last win back on May 12, 1962. On that day he pitched in relief in both games of a doubleheader against the Milwaukee Braves and won both games.

Anderson retired the Phillies in order through the first two innings. After he retired the first two Philadelphia batters on groundouts in the third, pitcher Chris Short singled for the Phillies’ first hit. Tony Taylor followed with another single that pushed Short to third. But Anderson got out of the jam when Johnny Callison hit into a third groundout to leave the runners stranded.

Short, a southpaw, started for the Phillies. He had started the season shakily and was just 1-8 on July 21. But over the next two months the lefty had gone 6-3 with an ERA of 2.30. Short had won his previous start, a four-hit complete-game victory over the Houston Astros, 3-2. It was his second complete-game win in a row.

Short got himself in trouble a few times early on as the Mets put runners in scoring position in each of the first three innings. He recovered each time and the Mets runners were left stranded. Twice Short ended a frame by striking out a batter. He later said he had to change his pitching stride due to the mound conditions: “In that first inning, I almost killed myself on that mound. They had slippery clay underneath the dirt. I kept shortening my strides so I wouldn’t step on it.”9

The Phillies finally got the best of Anderson in the fourth. Tony González reached base when Ron Hunt bobbled a groundball. It was “the opening they needed to score three unearned tallies”10 as Clay Dalrymple and Roy Sievers followed with singles before Bobby Wine’s two-strike triple cleared the bases. Stengel replaced Anderson with Roger Craig, who got the final out.

Jim Hickman led off the Mets’ half of the fourth with a home run, a shot that nicked the overhang in left field. It was his 17th round-tripper of the season, the most of any Met that season. It would turn out to be the only run the Mets would score all afternoon.

The Phillies added two more runs in the fifth. Taylor led off with a single and moved to second on a fielder’s choice. Wes Covington then singled Taylor home and was pushed to second on another fielder’s choice. Covington crossed the plate when Dalrymple singled. When the dust settled, the Phillies were ahead by four runs, 5-1. Craig was replaced by Ed Bauta, who pitched two scoreless innings before Larry Bearnarth took over for the last two frames, also keeping the Phillies in check.

But the five runs would be all Short would need. He shut down the Mets through the rest of the game, with the Mets getting hits in every inning but the seventh but never managing to bring a runner across home plate. With one out in the ninth, Rod Kanehl looped a single over the shortstop. Chico Fernandez hit a groundball single. Stengel sent Ted Schreiber to pinch-hit but he grounded into a double play to end the game.

The win kept the Phillies in the running for some of the postseason money. But manager Gene Mauch wasn’t just thinking about financial rewards: “I go out there expecting to win every game. I don’t see any reason why we can’t finish third. I just want us to finish as high as we can.”11

The small crowd that day did not represent the degree to which New Yorkers had already taken to their new ballclub. The crowd raised the Mets’ attendance to 1,080,108, fourth best in the National League. Gordon White wrote, “What seems more amazing is that this club, though still a sad bunch of major leaguers, drew 157,574 more fans than in 1962, when the newness of the Mets was the main factor in their good showing.”12

For the second time, the Mets had played their final game in the Polo Grounds. “On [this] last day,” wrote Red Smith, “the team and the customers and the script were tired. The weather was dismal. … Once more Nelson and Murphy held Stengel at the microphone. They played to an audience of cops, groundskeepers and news photographers. … From the public address system issued the canned strains of ‘Auld Lang Syne.’ The playing field was moist, but the eyes were dry.”13

Stengel perhaps summed it up best, saying, “It’s been a lot of fun in this park.”14

The Mets moved out of the Polo Grounds in January of 1964 and four months later the wrecking ball arrived. It was the same wrecking ball that had demolished Ebbets Field four years earlier. The wrecking crew wore Giants jerseys in homage to the team that had graced the ballpark for so many years.15

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org, for box-score, player, team, and season information as well as pitching and batting game logs, and other pertinent material.

baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYN/NYN196309180.shtml

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1963/B09180NYN1963.htm

Notes

1 Philip J. Lowry, “Polo Grounds (I) Southeast Diamond,” Green Cathedrals, Fifth Edition (Phoenix: SABR, 2020), 876 (ebook version of text for Mac).

2 Red Smith, “The Last Hurrah at Polo Grounds,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, September 19, 1963: 2D.

3 Smith.

4 Smith.

5 Gordon White, “Era of Mets Ends at Polo Grounds,” New York Times, September 19, 1963: 32.

6 Joe O’Day, “Baseball Sez Bye to PG; Phils Inter Mets, 5-1,” New York Daily News, September 19, 1963: 56.

7 O’Day.

8 Stan Hochman, “No Mere Sentimental Journey for Phils,” Philadelphia Daily News, September 19, 1963: 69.

9 Hochman.

10 Allen Lewis, “Phils Pin Mets Behind Short,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 19, 1963: 39.

11 Hochman.

12 White.

13 Smith.

14 O’Day.

15 Stew Thornley, “Polo Grounds,” in The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants (Phoenix: SABR, 2015), ebook.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Phillies 5

New York Mets 1

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.