Ed Bauta

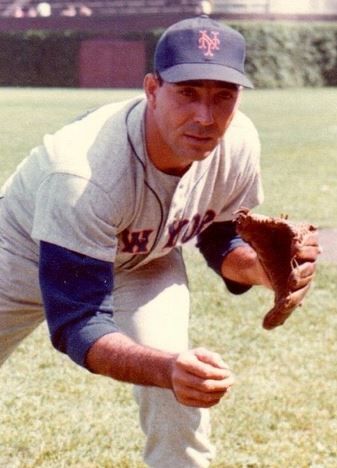

From 1960 through 1964, Cuban righty Ed Bauta pitched in one full major-league season and parts of four others with the St. Louis Cardinals and New York Mets. Bauta wasn’t a strikeout artist, averaging between five and six K’s per nine innings throughout his recorded pro baseball career. He relied on a sinker, thrown from varied arm angles – three-quarters and below. Fellow pitcher Harry Fanok, a teammate with St. Louis in 1963 and in the minors, described Bauta vividly. “Eddie was pretty tall [6-feet-3] and gangly. When he pitched, he looked like a giant spider. It looked like he had four legs and three arms, all of which came sort of sidearm or even submarine-style in his delivery. He had to be effective – he was always in spring training camp or being called up from Triple-A for another shot.”1

From 1960 through 1964, Cuban righty Ed Bauta pitched in one full major-league season and parts of four others with the St. Louis Cardinals and New York Mets. Bauta wasn’t a strikeout artist, averaging between five and six K’s per nine innings throughout his recorded pro baseball career. He relied on a sinker, thrown from varied arm angles – three-quarters and below. Fellow pitcher Harry Fanok, a teammate with St. Louis in 1963 and in the minors, described Bauta vividly. “Eddie was pretty tall [6-feet-3] and gangly. When he pitched, he looked like a giant spider. It looked like he had four legs and three arms, all of which came sort of sidearm or even submarine-style in his delivery. He had to be effective – he was always in spring training camp or being called up from Triple-A for another shot.”1

All of Bauta’s 97 appearances in the majors came in relief. He also pitched mainly out of the bullpen in the U.S. minors, where he appeared as late as 1973. Yet Bauta also found success as a starter in the Mexican Pacific League (winter ball) and the Triple-A Mexican League (summer). His best season came in 1973 for the Poza Rica Petroleros: 23-5, 23 complete games, seven shutouts. He also had a magnificent Caribbean Series in February 1974, as both starter and reliever.

Until he died in 2022, Bauta still got fan mail and baseball card autograph requests mentioning two notable moments in Mets history. He pitched in the final regular season game at the Polo Grounds (September 18, 1963) and was the losing pitcher as the Mets christened Shea Stadium (April 17, 1964). In between, he also became the last big-leaguer to hurl at the Polo Grounds, getting the final three outs for the National League in the Latin American Players’ Game (October 12, 1963).

Eduardo Bauta Gálvez was born in Florida, Cuba, on January 6, 1935. He was the first child of Pablo Bauta and Alicia Gálvez de Bauta. His siblings included Eneida, Pablo, and Norma. Eduardo’s birthday is Three Kings Day, a national holiday in many Spanish-speaking lands.

The work ethic that helped propel Bauta to the majors came from long hours of farming and sugar cane cutting in his homeland. Florida is in Camagüey Province, which is known for production of livestock, sugar cane, and other agricultural products. Pablo Bauta Sr. worked in the cane industry, ensuring that oxen did their work along six lanes. Ed Bauta dropped out of school at 10 to help his father, and did this until age 20. Bauta also picked yuca, the root of the cassava plant.

Bauta recalled, “I played baseball when time allowed. I would cry when it rained and my baseball games were called off.” He never played either Little League baseball or the equivalent of American Legion ball. Rather, he pitched in pickup and community-based games.2

Bauta’s favorite team in the Cuban winter league was the Almendares Blues, a.k.a. the Alacranes (Scorpions). “I was an almendarista de rabia [rabid Almendares fan],” he remembered. “I listened to their games on the radio at night.” Bauta never saw a game in this league while he was growing up, because his hometown of Florida was too far from Havana, where the circuit was based. Bauta never set foot in Havana until he pitched winter ball in Cuba. In the 1940s, it took 10 hours to drive from his part of the country to the capital city, mostly on two-lane roads. Even with the modern highway, it’s still a six-hour trip.

Almendares became champion of the Cuban league in the 1948-49 season. The Blues went on to win the first Caribbean Series in February 1949, defeating three other regional winter-ball champs. The team’s leader was Fermín “Mike” Guerra, whom Bauta called “a good catcher and a fine manager.” His favorite player, however, was slugger Roberto Ortiz. He was six years old when Ortiz made his big-league debut for the 1941 Washington Senators. Ortiz was a native of Central Senado, a plantation in a different part of Camagüey. Bauta called the 6-foot-4, 200-pound outfielder un guajiro grandísimo (one huge peasant).3 Ortiz later starred in a 1951 film about his life titled Honor y Gloria that was shown in Cuba’s best movie theaters.

In his teens, Bauta was in demand as a pitcher in Camagüey province. His big break came in December 1955, when Howie Haak, a Pittsburgh Pirates scout in the Caribbean, and Napoleón Heredia, his Cuban translator, watched him in a two-day tryout in the province’s main city, also called Camagüey. “I was in the (sugar cane) fields with an Afro-Cuban co-worker, and he asked me to pitch an amateur game against Camagüey…I struck out 14,” stated Bauta. “A midweek money collection was set up by the guajiros in Florida; I got $6 by Wednesday to go.4 Bauta hitched a ride to Florida, then took the bus 28 miles northwest to Camagüey city. He had a glove, but borrowed a uniform and cleats from a neighbor for his tryout. Bauta caught the first day and pitched the second day, standing out in a group of 153 prospects. Weeks later, a telegram came in notifying Bauta of a $500 bonus and his 1956 pro contract. Roberto Ortiz translated the pact into Spanish, a gesture of sentimental value to Bauta.

Bauta’s first two minor-league seasons were with the 1956 Clinton Pirates of the Midwest League (Class D) and the 1957 Grand Forks Chiefs of the Northern League (Class C). He got $3 in daily meal money; managers and players rode in vans to the games. As a part-time starter, Bauta’s stats were not imposing – yet he was the only prospect from either club to make the majors.

Bauta’s first experience in his homeland’s league came in the 1957-58 winter season, when he joined the practice squad of the Marianao Tigres. He remembered star pitcher Bob Shaw (Cuban League MVP that year), outfielder Solly Drake, as well as local hero Minnie Miñoso, who had the adjoining locker. “Minnie was very nice to me, a real gentleman,” said Bauta. Marianao repeated as league champion, but Bauta did not pitch in any regular season or postseason Cuban League games, nor did he travel to Puerto Rico for the Caribbean Series in February 1958.5

The Lincoln Chiefs of the Western League (Class A) came next. Bauta roomed with Dominican second baseman Julián Javier. “Big Ed” (as his teammates called him) pitched 74 innings in 48 games, all but one in relief. He went 7-6 with a 3.04 ERA. He recalled Al Jackson and Dave Wickersham as fine starters and U.S. Virgin Islander Elmo Plaskett as a talented hitter, but a bit lazy. Monty Basgall, the team manager, was a good baseball man, said Bauta.

Bauta advanced in 1959 to Triple-A Salt Lake City of the Pacific Coast League, where meal money was $5/day. The Bees went 85-69 under Larry Shepard to win the PCL title outright, with no postseason. Bauta put up numbers of 7-8, 3.86 in a campaign that included 10 starts, 29 relief appearances, and 112 innings. He bonded immediately with his roommate, Carlos Bernier, who had dropped out of school by age 11 and cut sugar cane in Puerto Rico. Another interesting teammate was pitcher Dick Hall, fluent in Spanish from playing winter ball in Mexico and marrying a lady from Mazatlán. Hall had an accounting degree and did the taxes for all his Latin American teammates, including Bauta and Bernier.

Bauta had pitched in just one game for Marianao in the winter of 1958-59 (striking out two in two innings). During the 1959-60 season, however, he really emerged: 6-4 with a 2.00 ERA in 103 innings across 25 outings, including three complete games. Bauta recalled that the entire team had a good laugh when Marianao manager Napoleón Reyes had a tantrum following a loss. Reyes, who weighed close to 280 pounds, kicked the team’s dirty uniforms in the clubhouse and fell down. By 1959, Bauta was married to his first wife. His son, Ed Bauta Jr., was born in 1960.6

Bauta started the 1960 season with another Pirates Triple-A club, the Columbus Jets, managed by Cal Ermer. Late that May, however, Jets GM Harold McKinley Cooper called Bauta with the news that he and Julián Javier had been traded to St. Louis for pitcher Vinegar Bend Mizell and utilityman Dick Gray The Pirates had Bill Mazeroski at second and were in need of a starting pitcher.

Bauta was actually a “player to be named later” and did not officially join the Cardinals organization until the second week in June. Just before the trade, he got hurt while swinging the bat on a lark. He’d accepted a dare from Columbus teammate Pidge Browne that he could hit at least one ball out of the infield if Browne made 10 pitches – and on the second pitch, he wrenched his right knee while taking a big cut. Bauta said, “June was spent in the St. Louis Cardinals training room with Bob ‘Doc’ Bauman.”7

Had he stayed with Pittsburgh, Bauta might have been able to pitch for a World Series champion that year, but once his fluid-filled knee got well enough, the move to St. Louis led to his major-league debut. It came at Chicago’s Wrigley Field on Wednesday, July 6, 1960 – and was a rough outing. George Altman hit three-run homers off Bauta in the seventh and eighth innings. Bauta stated “me cayeron a palos,” – i.e., “I was shelled.” He added that manager Solly Hemus told him not to worry, that it was his first game and that “tomorrow is another day.”8 Bauta pitched scoreless ball in his next six outings, but he gave up five runs in two subsequent appearances to finish with a 6.32 ERA (he received no decisions). He did not pitch again after September 2.

The 1960-61 season in Cuba was the last for Bauta and the nation’s professional league because Fidel Castro dismantled it and focused on amateur baseball. Bauta pitched in 24 games for Havana, going 4-4 with a 3.53 ERA in 95 innings for manager Tony Castaño.9

Bauta became angry when his winter salary was slashed from $1,000/month to $500/month. “The [Cuban] government cut our salaries in half, claiming their half would go to revolutionary causes,” said Bauta. “This was not right. I saved money by living in the same Havana house with José Tartabull. We took the bus together to the Gran Estadio, where all league teams played.”10

Bauta began 1961 at Portland in the PCL. A teammate, pitcher Dick Hughes, observed that the Cuban’s funny throwing motion made him effective. Off the field, the “very hairy” Bauta was “loosey-goosey, a happy-go-lucky type.”11

Portland was a significant stop for Bauta because he roomed with Craig Anderson, who became his longest-lasting friend from baseball, and played for Vern Benson, his favorite manager. They originally bonded because of Benson’s small-town North Carolina roots (Bauta called the skipper “un buen guajiro”) and because Benson had helped Havana win the 1952 Caribbean Series.

“I had the utmost respect for [Benson],” said Bauta, and the skipper returned the feeling by helping the pitcher get back to the majors. In 35 games for Portland, Bauta was 9-1 with a 1.95 ERA in 60 innings. After the Cardinals replaced Solly Hemus as manager with Johnny Keane in early July, Benson was promoted to the big-league coaching staff and put in a good word for Bauta.12

In two-plus months with St. Louis in 1961, Bauta was second on the club with five saves, behind Lindy McDaniel’s nine. He got his first win in the majors at home against the Dodgers on August 23. His longest effort was five scoreless innings at Crosley Field on September 9. He finished 2-0 for St. Louis with a 1.40 ERA in 19.1 innings.

In the winter of 1961-62, Vern Benson became manager of the Santurce Cangrejeros in the Puerto Rican Winter League. Under a working agreement with St. Louis, he brought Bauta, Bob Gibson, and Craig Anderson to Santurce. Benson’s own experience playing in Venezuela and Cuba helped determine which imports could be most helpful to the Crabbers.

Before arriving in Puerto Rico, Bauta met with fellow Cuban players in Miami to discuss whether they should remain in the U.S. or return to Cuba. Tony Taylor led this group, which included Tony González, Cookie Rojas, Luis Tiant, and Zoilo Versalles. Bauta remembered it as an emotional meeting. Attendees felt that the Cuban government was more interested in establishing the amateur Cuban National League after Castro had abolished the professional winter league. By 1962, the Castro regime required Cuban pro baseball players who wished to travel home to do so via Mexico. There were other political complications too: the U.S. had embargoed trade with Cuba and banned travel there. The Cuban big-leaguers continued their baseball careers in the U.S., along with winter ball in various Latin American circuits.13

Bauta was reunited with Julián Javier when the second baseman joined Santurce (the Dominican winter season was cut short in October 1961, in the aftermath of Rafael Trujillo’s assassination). Bauta made $1,100/month in Puerto Rico and his hotel across from Sixto Escobar Stadium was fine. However, he pitched only through Three Kings Day 1962 for the Crabbers, going 4-3 with a 3.92 ERA in 25.1 innings. He left after developing a sore/tired arm, and Benson sent him to St. Louis for treatment. Bauta affirmed that muscle problems in his pitching arm stemmed from getting up and warming up “so many times in the majors and minors.” He thought his sinker, which had good movement, would have been more effective had he been used strictly as a starter from age 21 on.14

Bauta’s roster spot was taken by Orlando Peña, whom Santurce claimed after he’d been released by San Juan. Bauta noted that his fellow Cuban threw a spitball, which was never part of his own repertoire. Santurce won the league title and 1962 Inter-American Series behind the pitching of Anderson, Gibson, and Peña.

Bauta’s arm bounced back in the spring, and he spent the first half of 1962 with St. Louis. He won his only big-league decision that year on May 26, when Curt Flood’s game-ending single gave the Cardinals a 4-3 win over Milwaukee. Bauta’s ERA was 1.04 after this game, but it soared in June and reached 5.01 after allowing six earned runs in two innings versus Pittsburgh on June 30. He gave up two home runs by Smoky Burgess_top and was sent to Triple-A Atlanta.

Joe Schultz, Atlanta’s manager, was the right tonic for Bauta. Both drank a lot of beer on the team bus during July and August. “I really liked him (Schultz),” said Bauta. “Joe got in trouble for drinking beer on the bus and allowing players to drink beer! He bought beer for himself, and the players chipped in for part of the expenses.”15

Bauta called his catcher with the Crackers, Tim McCarver, “the best I ever pitched to, no question. He knew how to frame a pitch…very smart, easy to work with.” Atlanta also had Valmy Thomas, who’d caught Bauta with Santurce.16

Harry Fanok was with Atlanta that year too and had another colorful memory of Bauta from a visit to Columbus. Several players, all casually dressed, were outside the hotel when out the door strolled “ole Eddie, dressed to kill! He had a suit and tie that was outstanding, Versace, or damned close, and a shiny pair of Florsheims going on as well…looking like the first coming of Antonio Banderas!”17

Bauta’s 5-2 ledger, with a 1.96 ERA in 46 innings, helped Atlanta get to the postseason. The Crackers won the International League title in 1962, and Bauta got a ring and a gold watch. They also beat Louisville in the Little World Series. Yet the success was bittersweet for Joe Schultz because news of his firing broke before the season ended.

Ahead of the 1962-63 winter season, Commissioner Ford Frick issued a mandate that prevented Latinos from playing winter ball in countries other than their own. This unfairly hampered Cubans, including Bauta, who worked instead in the men’s clothing department of a Sears Roebuck store in Boise, Idaho.18 Several years later, the policy was relaxed under Frick’s successor, William Eckert – most likely through the efforts of Cuban baseball man Bobby Maduro, whom Eckert hired in December 1965. The edict had been loosely enforced, however; Bauta pitched one winter in the Dominican Republic (1963-64) and another in Nicaragua (1965-66).

The 1963 season was Bauta’s only full one in the majors. With St. Louis, he was 3-4 with a 3.93 ERA in 38 games for Johnny Keane. Bauta roomed with Julián Javier and enjoyed pitching to Tim McCarver. Bauta’s third save, on May 30, lowered his ERA to 1.69. On June 19, he pitched four-plus scoreless innings against the Mets for his third win.

On July 28, however, Bauta blew a save at Wrigley Field. Three days later versus Cincinnati, he allowed three earned runs in two innings. That sealed his fate. On August 5 (an off-day), Bing Devine told him he was traded to the Mets for lefty Ken MacKenzie.

Bauta felt that he should start for the Mets, but this was not to be. He hinted that the Mets management treated him like a commodity – someone to warm up frequently and use infrequently. Even so, he greatly admired his new manager. “I adored Casey Stengel,” said Bauta. “He knew more [baseball] than anyone else in baseball. Sometimes, on the plane, he was drinking vodka and spoke to me. He spent most of his time with the 40 (New York) writers after home games.”19 After the trade, Bauta had a 5.21 ERA in 19 innings across nine games, with no decisions.

The only Met fluent in Spanish besides Bauta was a U.S. Virgin Islander, Joe Christopher. Bauta was most comfortable with Latinos such as Bernier; in particular, he missed Javier. When his good friend Craig Anderson rejoined the team that September, though, it was a positive for Bauta. Anderson started the Mets’ final game in the Polo Grounds on September 18, and Bauta relieved in the sixth after Christopher pinch-hit for Roger Craig. He pitched two scoreless innings in a 5-1 loss to the Phillies attended by 1,752.

The following month, Bauta was one of 16 Cubans present at the Polo Grounds for the stadium’s baseball finale: the charity game pitting Latin American players from the AL, with manager Héctor Lopez, versus the NL squad, managed by Roberto Clemente. “I was married, living in New York City, at an apartment near the Polo Grounds,” said Bauta. As for his performance that day, he was still remorseful 55 years later. “I did not pitch well – we were up 5-0 in the ninth; I gave up two runs; felt like I LOST it for the National League…wanted to shut out the American League.”20 Orlando Cepeda may have said it best: “It didn’t matter that it was for charity and that it wasn’t a ‘real’ all-star game. When you put on your uniform, you played hard and tried even harder to win. And that’s what everybody did in that game.”21

Bauta spent the 1963-64 winter season playing for Estrellas Orientales in the Dominican Republic, where he’d had his car shipped from New York. He showed he had the mettle to start, which he did 14 times in 18 appearances. He threw six complete games, including three shutouts, and finished with a 2.94 ERA in 107 innings. His 7-5 record was notable because Estrellas (24-35) finished last. Bauta visited with Dick Hughes (Licey), Julián Javier (Aguilas Cibaeñas), and Minnie Miñoso (Escogido). He also got together with Vern Benson, who was Licey’s manager. “He loved to fish on a boat. When we played at San Diego [in 1961] and Santo Domingo, we fished. I got seasick and vomited both times!”22

Bauta was again part of history on April 17, 1964, when Shea Stadium had its grand opening in front of 50,312 fanatics. He relieved Jack Fisher in the seventh and gave up RBI singles to Donn Clendenon and Bill Mazeroski in the Pirates’ 4-3 win. History repeated itself on May 3, when Bauta blew a one-run lead at Cincinnati, allowing two eighth-inning runs. Stengel summoned Bauta from the bullpen for the final time in the majors on May 9, at Shea. He allowed three inherited runners to score, and gave up another run on three hits in one and two-thirds innings. Tim McCarver, the last big-league hitter he faced, grounded out. Bauta (0-2, 5.40 in eight games) kept it simple: “I lost two in relief; Casey called me into his office and sent me to Buffalo.”23

Bauta won eight of 12 decisions with Buffalo, starting once in 42 games, with a 3.00 ERA. Whitey Kurowski’s team made the IL playoffs, though the Bisons lost to Syracuse in seven. Craig Anderson also pitched for Buffalo in 1964. Winter-league coverage in The Sporting News showed no action for Bauta in 1964-65.

Bauta’s 1965 summer season began with Buffalo, but after appearing in 35 games (2-6, 3.52), he was loaned to Triple-A Rochester in the Baltimore system. He enjoyed Rochester, going 3-1, 3.24 in 12 games. He noted that manager Darrell Johnson “made an effort to know me, but got mad when I did not try to hit a batter after two of our guys were drilled, and took me out of the game.” Bauta said that he never threw at a hitter and tried to tell Johnson he was not sure how to do it. He bore no malice on the field.24

Bauta then pitched in Nicaragua in the winter of 1965-66. “Oriental de Granada was the military (Somoza’s) team,” said Bauta, referring to the nation’s future dictator, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, then commander of the National Guard. “I met him before one of our home games.” There were two teams in Managua – Bóer and Cinco Estrellas – plus Leones de León and Oriental. “A lot of Cubans played in Nicaragua; Angel Scull was my teammate,” said Bauta. “My manager was Cuban Wilfredo Calviño. I loved Granada.”25 Though many Cubans plied their trade in Nicaragua, Bauta did not socialize with them, opting to enjoy a new country and its amenities on his own.

However, Bauta suffered severe arm fatigue in early January 1966, which he attributed to constant warming up in 1964 and 1965.26 After taking 1966 off, in 1967 he pitched for Triple-A Jacksonville (0-1, 6.50 ERA) and Double-A Williamsport. He enjoyed Jacksonville’s nightlife too much, but performed superbly at Williamsport: 4-3, 0.77 ERA. By then 32, Bauta watched Mets prospects Gary Gentry, Jon Matlack, and Jim McAndrew being groomed.

Bauta’s first foray into Mexico was in 1967-68 with the Ostioneros de Guaymas of the Sonora-Sinaloa Winter League (renamed the Mexican Pacific League or LMP in 1970-71). Miguel “Pilo” Gaspar, Guaymas manager, and Francisco “Gallo” Rodríguez, the GM, picked Bauta up in Tucson, Arizona, for the 325-mile trip south to Guaymas. The border patrol agent in Nogales, Arizona, was demanding about letting vehicles cross. José “Chepe” Velarde, a Mexican umpire, suggested that the group rent a Red Cross ambulance, and put Bauta on a stretcher. The GM and manager put on male nurse outfits, for an authentic look. They activated the ambulance siren before arriving in Nogales. A mentholated balm covered Bauta’s neck and chest. When the Nogales agent opened the ambulance door, he saw Bauta in a cadaver-like state, and yelled, “Continue on your way, this man is gravely ill!” Further down the road, the group moved into their other vehicle, which was being driven by a real male nurse!27 Guaymas (58-26) won the 1967-68 league title with Ronnie Camacho, who replaced Gaspar, at the helm.

The Mets asked Bauta to take another step down in 1968, to Class A. For Visalia in the California League, he posted marks of 11-6 with a 2.16 ERA. Unusually for him, he struck out 128 in 96 innings, while allowing just 13 walks.

From 1969 to 1974, Bauta pitched in the Triple-A Mexican League with Poza Rica Petroleros. He stayed in Mexico for winter ball with the Culiacán Tomateros, 1969-70 league champions. He also returned to the U.S. for two stints with the Triple-A Eugene Emeralds in 1972 and 1973.

With Poza Rica in 1969, Bauta went 8-16, though he posted a sharp 2.67 ERA thanks to five shutouts. For the Petroleros in 1970, skipper Dave Garcia used Bauta 46 times in relief and gave him eight starts; he ended up at 9-8, 3.13. Bauta made 21 relief appearances for Poza Rica in 1971, going 3-1, 2.50.

A fine 1972 season with the Petroleros followed – 12-10, 1.91 ERA, six shutouts. Thus, Bauta earned a minor-league contract with the Philadelphia Phillies that August. The chance came courtesy of Rubén Amaro Sr., who had played with and managed Bauta at Culiacán and had recently become a scout for the Phillies. According to Bauta, Amaro (whose father, Santos Amaro, was Cuban) had a soft spot for him.28

Bauta was assigned to Philadelphia’s top farm club, Eugene, and he pitched in 12 games for the Emeralds in 1972 (2-3, 3.24). Mike Schmidt was the Phils’ top prospect at Eugene, and Bauta remembered him as “very serious.” The Cuban vet socialized with three Puerto Rican pitchers: Jesús Hernaiz (then aged 27), Manny Muñiz (24), and Luis Peraza (30).29

After pitching in the PCL playoffs, Bauta then took part in the Kodak World Baseball Classic at Honolulu Stadium in Hawaii. He was a member of the winning team, the Caribbean All-Stars, and was the tournament’s busiest pitcher, going 1-1 with a save in five games. Attendance was very poor, though, so the competition was not held again.30

Bauta went 23-5 in 30 starts for the Petroleros in 1973, completing 23, with seven shutouts sparking a 2.25 ERA. His 228 innings were the most he ever pitched. Bauta and George Brunet led Poza Rica (79-53) to their first postseason in years. They were also best friends and drinking partners. “I loved it in Mexico,” Bauta said. “Started out earning $500 a month; increased to $1,500 a month in 1973 when I kept winning. Flames from oil fields would get very hot…kept cool by drinking beer.”31

Bauta bested the Mexico City Diablos Rojos and their ace, Pedro Ramos, 1-0, in Game One of the first-round playoff series. Ramos and Bauta were both 38 when they faced each other that postseason. Ramos was from Pinar del Río, in the westernmost part of Cuba, known for tobacco growing. The veterans shook hands at game’s end.32 Mexico City then won three in a row to advance to the semi-finals, behind the pitching of Julio Navarro, Aurelio López, and Ramos.33

Bauta returned to Eugene in August 1973 (along with Brunet) and pitched well again: 3-0, 3.13 ERA in 23 innings. Jim Bunning, Eugene’s manager, told him he might join the Phils, but the call never came because they were the only team in the NL East that September to fall out of the hunt for the division title.

With Culiacán in the 1973-74 winter season, Bauta was 6-5 with a 2.00 ERA in 108 innings across 15 games. He joined the Ciudad Obregón Yaquis as a reinforcement for the Caribbean Series, hosted by Hermosillo, in February 1974. On February 1, he pitched 7.2 scoreless innings in relief versus Puerto Rico’s representative, Caguas, in a 2-1 loss. The Criollos, boasting a very strong lineup, went on to win the tourney. They had two Hall of Famers: Mike Schmidt and catcher Gary Carter (then a 19-year-old prospect). Their outfield had Jay Johnstone, Jerry Morales, and Otto Vélez. Their infield included Willie Montañez, Félix Millán, and Rudy Meoli.

Two nights later, Bauta went the distance in a 5-1 win. He threw a four-hitter against the defending champion Licey Tigres, managed by Tom Lasorda. After a first-inning run and three hits, Bauta allowed only a Bill Buckner single the rest of the way. On February 6, he pitched two relief innings, allowing an unearned run after a Steve Garvey infield hit and two errors.34

Bauta enjoyed drinking with Mexican slugger Héctor Espino during that Series. “Héctor was my Hermosillo roommate,” he said. “He drank a lot, but was a tremendous hitter. I was drunk before and after each of the [1974] Caribbean Series games.35 Nonetheless, Bauta was named to the All-Star team of that series as the right-handed pitcher: 1-0, 0.48 ERA, 11 strikeouts, one walk, and 18.2 innings. Espino was the All-Star first baseman and series MVP.36

Bauta pitched one final summer season with Poza Rica in 1974, going 9-15 with a 2.99 ERA in 26 starts and six relief outings.37 He pitched with Culiacán in the LMP in 1974-75, and retired after a season of semi-pro ball with El Mante, Mexico, in 1975.

Bauta relocated to Paterson, New Jersey, in 1975. While living in New Jersey, Bauta hooked up with Carlos Bernier, and in 1978 they attended a Jersey City A’s home game. The Class AA club featured Rickey Henderson, then an A’s prospect.

Bauta worked in the moving business – transporting furniture – until 1988. “This was tough on my knees,” he noted. “Had both knees replaced, got tired of the cold, and moved to Daytona Beach in 1988; have lived there ever since.”38

As of his 80s, Bauta no longer followed major-league ball. He was content to work out three times a week and walk his very special beagle, Puchi. He periodically visited Alicia Janeth, his daughter, in Cancún. He liked it that Craig Anderson was living in Dunnellon, Florida, 100 miles west of Daytona Beach. Bauta was content with his baseball achievements, knowing he pitched with dedication, honor, and dignity until age 40.

Bauta’s last few years were spent in assisted living at the Benton House, Port Orange, Florida, prior to relocating to Manahawkin, an unincorporated community in Ocean County, New Jersey, in the final portion of his life. Bauta passed away in Manahawkin, on July 6, 2022, at age 87.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Ed Bauta for May-September 2018 phone interviews. Craig Anderson had input as Bauta’s teammate with St. Louis, New York Mets, Santurce Cangrejeros, Portland and Buffalo. Dick Hughes shared memories on Bauta as his Portland/Atlanta teammate. Harry Fanok, St. Louis/Atlanta Crackers teammate, had colorful Bauta insights. Jorge Colón Delgado furnished Bauta’s Santurce pitching stats. Daimir Díaz Matos, Palma Soriano, Cuba, provided Roberto Ortiz research. Eduardo Almada shared a 1974 Caribbean Series summary, Bauta’s 1973-74 Culiacán stats, and the fabulous story on Bauta’s initial foray into Mexico. Monte Cely, Rogers Hornsby SABR Chapter, put Almada in touch with the author.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Articles

Markusen, Bruce. Cooperstown Confidential: The wild life of George Brunet, April 26, 2013. https://www.fangraphs.com/tht/cooperstown-confidential-the-wild-life-of-george-brunet.

Books

Figueredo, Jorge S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland Publishers, 2007.

Johnson, Lloyd and Miles Wolff (editors), Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Third Edition, 2007.

Treto Cisneros, Pedro (editor), Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano, Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V.: 11th edition, 2011.

Van Hyning, Thomas E. The Santurce Crabbers, Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland Publishers, 1999.

Internet

http://history.winterballdata.com/?view_page=team&season_id=11&phase_id=1&team_id=4&s_ok=Ver+Equipo

https://martindihigoelmejor2013.cubava.cu/files/2015/12/Anuncio-del-filme-Honor-y-Gloria.jpg

https://supercuba.wordpress.com/2011/07/14/roberto-ortiz-el-guajiro-gigante/

https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/roster/t-cj11031/y-1960

Notes

1 E-mail, Harry Fanok to Rory Costello, July 16, 2018.

2 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, May 30, 2018.

3 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, July 13, 2018.

4 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, May 30, 2018.

5 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, May 30, 2018.

6 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, June 2, 2018. Bauta did not provide the names of his ex-wives (one Cuban, one American). Bauta told the author he has “fathered a number of children, at least five or six unofficially.”

7 Neal Russo, “Bauta Takes Bows as Boss of Redbirds’ Busy Bull Pen,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1963, 34. Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, May 30, 2018.

8 Ibid.

9 His final Cuban Winter League record: 10-8 with a 2.70 ERA in 200 innings across 50 appearances, including five complete games.

10 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, July 13, 2018.

11 Dick Hughes, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, July 14, 2018.

12 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, July 13, 2018.

13 Ibid.

14 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, June 29, 2018.

15 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, June 5, 2018.

16 Ibid.

17 E-mail, Harry Fanok to Rory Costello, July 16, 2018.

18 Russo, “Bauta Takes Bows as Boss of Redbirds’ Busy Bull Pen.”

19 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, June 2, 2018.

20 Ibid.

21 Robert Dominguez, “The forgotten all-star game,” New York Daily News, July 10, 2013.

22 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, May 30, 2018.

23 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, June 2, 2018.

24 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, June 5, 2018.

25 Ibid.

26 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, July 13, 2018. The Sporting News, January 15, 1966 edition mentioned that Oriental signed pitcher Scott Seger to replace Bauta.

27 E-mail, Eduardo B. Almada to Tom Van Hyning, August 13, 2018. Eduardo is the son of Mel Almada, first major-league player born in Mexico.

28 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, September 27, 2018.

29 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, June 5, 2018.

30 “Classic Comments,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1972, 31.Joe Marcin, “World Baseball Classic a Financial Fizzle”, Sporting News Baseball Guide, 1973.

31 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, June 5, 2018.

32 Ibid.

33 Tommy Morales, Cápsulas históricas, Mexican League News (/LMB/NEWS), August 3, 2015. Accessed at https://www.milb.com/lmb/news/calvi241o-y-el-diablos-rojos-de-1973/c-140736076, on July 31, 2018.

34 Eduardo B. Almada, Summary of “XVII Serie del Caribe 1974,” e-mailed to Tom Van Hyning, August 11, 2018.

35 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, June 29, 2018.

36 Summary of “XVII Serie del Caribe 1974.”

37 Bauta’s 1969-1974 Mexican Summer League record: 209 games, 112 starts, 59 complete games, 21 shutouts, two saves, 64-55, 2.55 ERA, 973.1 innings, 939 hits allowed, 475 strikeouts and 187 walks.

38 Ed Bauta, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, June 2, 2018.

Full Name

Eduardo Bauta Gálvez

Born

January 6, 1935 at Florida, (Cuba)

Died

July 6, 2022 at Manahawkin, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.