September 21, 1938: Storm of the Century hits Boston’s Braves Field

“Peace in our time” dominated international headlines everywhere on September 21, 1938. The words were spoken by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain after he signed a pact with Hitler giving Nazi Germany control over the German-speaking Sudetenland section of Czechoslovakia. In the Northeastern United States, a more immediate disaster was headed its way – the worst hurricane in New England history, one for which residents were totally unprepared.

“Peace in our time” dominated international headlines everywhere on September 21, 1938. The words were spoken by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain after he signed a pact with Hitler giving Nazi Germany control over the German-speaking Sudetenland section of Czechoslovakia. In the Northeastern United States, a more immediate disaster was headed its way – the worst hurricane in New England history, one for which residents were totally unprepared.

One survivor of the storm recalled 50 years later “(W)e had no warning whatsoever.” Earlier in the day a Coast Guardsman had commented, “Gee, it’s a strange day.”1 Typically these storms would come up the Atlantic seaboard and then veer out to sea. Not this one; it slammed into land with a triple punch – 100-plus-mph winds, Noah’s Ark-type rain and abnormally high tides.2 “Hurricanes are tropical children, the off-spring of ocean and atmosphere, powered by heat from the sea. They are driven by their own fierce energy,” a government publication noted.3

One survivor of the hurricane reminisced that he was sent home early from grammar school, simply being warned “to be careful.”4 No one knew of the danger from fallen wires and downed trees. Movie star Katharine Hepburn spent the morning in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, “swimming and playing nine holes of golf.”5 She nearly drowned as the venerable family home, Fenwick, was carried away.

Meanwhile, in Boston, Paul Shannon wondered that morning in the Boston Post “if the Bees and Cards may play two today at the Bee-hive (aka National League Park) if the weatherman relents. The outfield looks like a swamp.”6 In fact, because of rainouts, the entire National League schedule that Wednesday afternoon was for doubleheaders, all in the four Northeast cities. (American League teams that day were playing in what was then called “the West” – Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and St. Louis – where conditions were drier.) Hank Greenberg led the majors with 53 home runs and Mel Ott paced the senior circuit with 33. Jimmie Foxx had an amazing 161 RBIs in just 141 games. The first-place Yankees lost their fifth straight, to Monty Stratton and the White Sox. The Boston Bees were in fifth place in the National League, 12 games behind the first-place Pittsburgh Pirates, and the St. Louis Cardinals were 2½ games behind the Bees.

On that fateful Wednesday, September 21, Bees president Bob Quinn opened the ballpark gates with some reluctance to accommodate the few fans who had shown up.7 The Bees were 69-69 in an annual struggle to finish above .500. Their lineup could be called “modest.” Only Al Lopez (2), Vince DiMaggio (2) and Lou Fette (1) ever made an All-Star game, and then it was mostly in wartime. Lopez did make the Hall of Fame but it was not because of his .241 batting average in Boston. Nor were these still the once-powerful Gas House Gang Cardinals – Dizzy Dean, Frankie Frisch, and Leo Durocher were gone but Joe Medwick and Pepper Martin were still on hand and Johnny Mize and Enos Slaughter had arrived. In the first game of the twin bill, Medwick’s eighth-inning homer off Jim Turner drove in three runs and Paul Dean scattered seven hits to shut out the Bees, 4-0. Shannon’s comment was: “Seldom has a more listless performance been given by the locals.”8

By the time Game Two began, the storm and winds (and even snow) were much stronger. Boston hurler Lou Fette (10-13) and St. Louis rookie Mort Cooper (1-0) were the starters. Each gave up a single and no runs. Hal Epps led off for the Birds by beating out an infield roller, which was followed by a Boston error, but Fette pitched out of the jam. Third baseman Joe Stripp “connected for the home team”9 in the second, but by now “the elements were doing weird things with balls hit into the air.”10 Bees rookie Ralph McLeod, who had gotten his first big-league base hit in the first game as a pinch-hitter, remembered in a 1995 interview, “Part of the fence blew down. They had to stop the game and make up new ground rules. Balls hit to center ended up foul in left. The hurricane game was cut short at Braves Field (sic), the umps called it when Fletch’s pop fly was blown into the right field stands.”11

Boston first baseman Elbie Fletcher’s recollections, while vivid, also do not seem entirely accurate. “In a September 1938 afternoon game against the Cubs (sic), Fletcher noticed that the wind was whipping up stronger than usual and the sky was getting dark, but they kept on playing. Then a big billboard behind the left field fence blew down and infield dirt was whirling around pretty good. Occasionally someone’s hat would blow off, but they still kept at it. Then a Cub hitter lifted a pop fly over first base that Fletcher called for, then the shortstop was calling for it, then the left fielder and finally it blew right out of the park, an infield fly home run. At that point the umpires called the game, and it wasn’t until Fletcher left the ballpark that he realized the enormity of the storm.”12 Both of these versions, told decades after the game, smack of the anecdotal, told in an old boys’ way of storytelling, more for humorous hyperbole than for accuracy. So not even first-person accounts are always entirely reliable. (The “billboard behind the left field fence” presumably was the “part of the fence” mentioned by McLeod.)

Baseball Digest also rendered an inaccurate report, writing that “the game was called when Elbie Fletcher hit a popup that was blown wildly into the stands.”13 A more reliable description came from Herb Davis of Douglas, Massachusetts, who wrote that the game was called “when Bees second baseman Tony Cuccinello called for a popup behind second base only to have catcher Al Lopez make the catch at the backstop.”14 Three Boston dailies, the Globe, Herald, and Post reported unanimously that “the game was called with one out in the top of the third” by umpire Beans Reardon, which means that the Cardinals were batting, not the Bees. All records were erased so there is no definitive account of the game. The Herald featured a picture of four nattily dressed Cardinals, Piere (sic) Lanier, Paul Dean, Morton Cooper, and Max Macon, “taking refuge under Beehive on day of big wind,” as “storm interrupts finale.”

The Bees did win the next day’s makeup game; in fact they won both tilts that day, 6-5 and 4-1. The Cardinals made major-league history by leaving Boston right after the game – by chartered airplane. This was the first time that a major league club chose to fly during the season.15 Interestingly, the Giants than arrived in The Hub by overnight boat, arriving early Friday morning – for two more doubleheaders, on both Saturday and Sunday. The voyage was necessitated because the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad was out of commission after the hurricane.

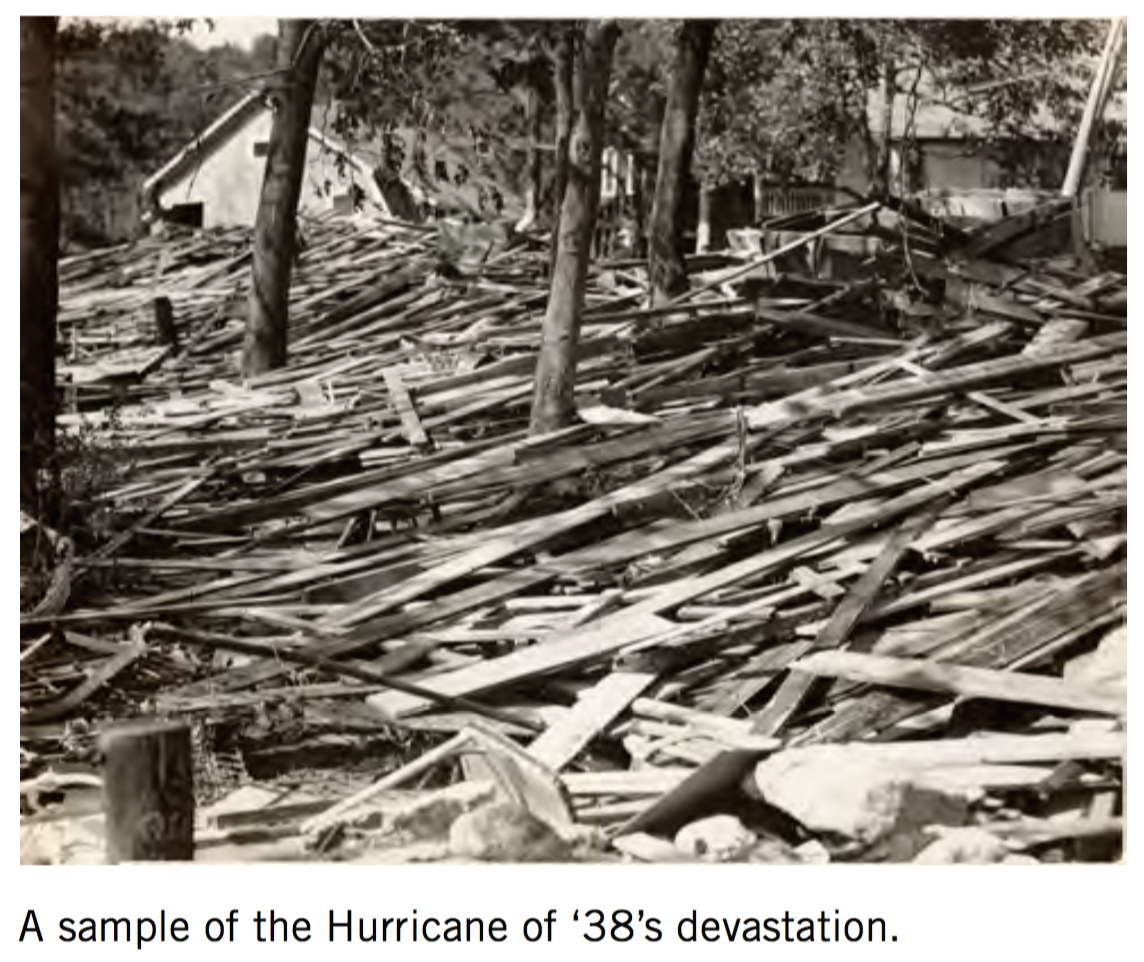

Aftermath of the storm: Almost 700 lives were lost. Property damage was estimated at $306 million, the equivalent of $4.6 billion in 2014 dollars. In 1938 the minimum wage was 25 cents an hour.16 War did start, in September 1939, but life and baseball went on, and the Cubs, not the Pirates, won the pennant after Gabby Hartnett’s “Homer in the Gloamin’.”

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, box scores for this game can be seen on baseball-reference.com, and retrosheet.org at:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN193809210.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1938/B09210BSN1938.htm

Notes

1 James Nestor, quoted in the Providence Journal-Bulletin, September 21, 1988, 1.

2 The Storm, a publication of the Blue Hill Observatory (Green Hill Books, Randolph Center, Vermont, 1988).

3 Hurricane, the Greatest Storm on Earth, US Department of Commerce, 1973, 3.

4 Recollection of Leonard Levin, mentioned to author.

5 Jennifer Steadman, “Katharine Hepburn, Fenwick and the Hurricane of 1938,” WNPR News, June 27, 2014.

6 Paul Shannon, Boston Post, September 21, 1938, 14. According to the Globe, the Braves reported the attendance as 1,356, “but that must have indicated ushers, players, press et al.”

7 Shannon.

8 Shannon.

9 Gerry Moore, Boston Globe, September 22, 1938, 22. Despite the inference, Stripp’s hit was a single, not a home run.

10 Moore.

11 Dick Thompson, “An Afternoon With Ralph McLeod,” The National Pastime, Volume 16, 1996. McLeod did not elaborate on “new ground rules.”

12 Steve Wallace blog, “Boston Blow-Up.”

13 Baseball Digest, January-February 2007, 10.

14 Herb Davis, letter to Baseball Digest, January-February 2007, 10.

15 Burt Whitman, Boston Herald, September 23, 1938.

16 The Storm, Blue Hill Observatory.

Additional Stats

St. Louis Cardinals 4

Boston Bees 0

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.