Georgia’s 1948 Phenoms and the Bonus Rule

This article was written by Wynn Montgomery

This article was published in Summer 2010 Baseball Research Journal

In the summer of 1948, two of the nation’s premier major-league pitching prospects were Georgia boys—Willard Nixon of Lindale and Hugh Radcliffe of Thomaston. Both were multisport stars with a special talent for baseball. Both were big, strong, righthanded pitchers who had dominated opposing batters wherever they had pitched. Both attracted the attention of almost every major-league baseball club. And as a result, each had to make a difficult, life-altering decision because of the “bonus rule” that was in effect at the time.

EVOLUTION OF THE BONUS RULE

A few players had received sizable signing bonuses during the 1930s. For example, the Yankees paid Charlie Devens $20,000 in 1932 and Tommy Henrich $25,000 in 1936.[fn]Brent Kelley, Baseball’s Biggest Blunder: The Bonus Rule of 1953–1957 (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Books, 1997).[/fn] Henrich, however, was not an untried player, having spent three productive years in the minor leagues. Despite such early bonuses, most baseball historians identify Dick Wakefield as the first member of the group that would be forever known as the “Bonus Babies.” In 1941, the Detroit Tigers signed Wakefield out of the University of Michigan for $52,000 and a new car.

As the sportswriter (and later novelist) Paul Hemphill observed: “Once bonus fever set in, there was no stopping it.”[fn]Paul Hemphill, “Whatever Happened to What’s-His-Name?” True (June 1972). Collected in Paul Hemphill, Lost in the Lights: Sports, Dreams, and Life (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2003).[/fn] Perhaps not, but the owners certainly tried. Steve Treder suggests in The Hardball Times that the motivation behind the bonus rule was twofold. Club owners were interested in competitive balance and sought a way to keep the richer clubs from cornering the market on top prospects. These moguls also wanted to hold down their labor costs, both for new signees and for the increasingly disgruntled established stars, who resented making less than untried “phenoms.”[fn]Steve Treder, “Cash in the Cradle: The Bonus Babies,” The Hardball Times (11 November 2004).[/fn]

The size of signing bonuses continued to creep upward as the Yankees (again!) paid Bobby Brown $60,000 in 1946. Earlier that year, baseball’s majorleague owners proposed restrictions that, according to John Drebinger of the New York Times, “virtually outlaw bonus payments” because the “heavy and complicated restrictions . . . make it unlikely that any Major League club will care to take the risks involved except in very rare cases.”[fn]John Drebinger, New York Times, 3 February 1946.[/fn] The proposed restrictions on bonus payments received approval from the minor leagues (the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues) and took effect in 1947.

This original bonus rule stipulated that any player signed by a major-league team for a salary/bonus package exceeding $6,000 had to be placed on the major-league roster before the end of the season or be declared a free agent, claimable by any other majorleague (or higher-classification minor-league) team. Similar restrictions applied to minor-league clubs, with a sliding scale for the amount at which the bonus rule kicked in. This scale ranged from $4,000 for triple-A teams down to $500 for Class E teams. The rule also specified that a bonus player retained this designation throughout his career.

The new rule may have slowed the bonus bandwagon, but it certainly did not bring it to a halt. A significant new bidder did, however, hop aboard. In 1947, the Philadelphia Phillies, under new ownership, shelled out bonuses to two high-school pitchers— $15,000 to Charlie Bicknell and $65,000 to Curt Simmons. The latter bonus was by far the better of the two investments; both were sizable when compared to the average ballplayer’s annual salary of approximately $11,000.[fn]Michael J. Haupert, “The Economic History of Major League Baseball,” in EH.Net Encyclopedia, ed. Robert Whaples; “The Century in Dollars and Cents,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer (2002), www.seattlepi.com/specials/moneyinsports/sportstimeline.pdf.[/fn] (The median annual family income at that time was $3,031.)[fn]U.S. Census Bureau’s Historical Income Tables-Families, www.census.gov.[/fn]

The following year, the Phillies again were major investors in the bonus market. The Boston Braves paid the highest premium for a single player—$65,000 to Johnny Antonelli—but Philadelphia signed three young pitchers for a combined bonus total of $85,000. Bob Miller, out of the University of Detroit Mercy, received $20,000; Robin Roberts, from Michigan State University, pocketed $25,000; and Georgia schoolboy Hugh Radcliffe accepted the Phils’ offer of $40,000.

Few believed that the bonus rule was the solution to the spending problem, and many openly criticized its intent, its effectiveness, and its impact on the young players who fell under its restrictions. It is not surprising, considering his team’s heavy investment in young talent, that Philadelphia Phillies owner Bob Carpenter called the rule “the most unfair piece of legislation in baseball.” Carpenter, who had opposed the adoption of the rule and led several unsuccessful efforts to have it repealed, elaborated on his objections, saying: “It is not only unfair to the clubs who are willing and eager to improve their positions, but doubly unfair to the players themselves. There is no doubt that the necessity of keeping youngsters on the Major League roster has retarded their progress.” He went so far as to label the rule more than unfair, calling it “unAmerican” and asking: “Have you ever heard of any business other than baseball which penalizes a club for making improvements?”[fn]Salt Lake City Desert News, 20 October 1949.[/fn]

Carpenter was not alone in his criticism of the bonus rule. Connie Mack, owner and manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, observed that “the bonus rule hurts the player, the club, and all baseball.”[fn]Frank Eck, Massillon (Ohio) Evening Independent, 2 July 1948.[/fn] Baseball Commissioner “Happy” Chandler called the rule a “restrictive yoke,”[fn]Charleston (W.V.) Daily Mail, 4 December 1949.[/fn] and American League President Will Harridge labeled it “a long-range boomerang to promising youngsters.”[fn]New York Times, 3 April 1948.[/fn] Leaders of independent minor league teams, such as the Atlanta Crackers’ Earl Mann, recognized that the rule would undermine their ability to compete for new young talent and actively campaigned against it.

The criticism was not unanimous, however. Warren Giles, Cincinnati’s president and general manager, maintained that “if a player is worth a substantial bonus, he should have sufficient ability to play in the majors at the time he signs and not have to spend several years developing.”[fn]Portsmouth (Ohio) Times, 4 June 194).[/fn] The varying opinions and the intensity of those feelings made the bonus rule a topic of discussion at every owners’ meeting and resulted in frequent tinkering with its finer points.

In 1949, for example, the rule was modified to allow certain bonus players signed after March 31 that year to be optioned once during their first year. The “bonus” level for triple-A and double-A teams was increased to the major-league level of $6,000. This latter change was a partial response to a proposal from George M. Trautman, president of the NAPBL, that all leagues have the same limit to prevent clubs from signing players at a higher level to avoid the bonus designation and thus requiring them to face stiffer competition than they were ready for.

By late 1949, however, the handwriting was on the wall—or at least in the New York Times. In a column entitled “End of a Noble Experiment,” Arthur Daley compared the bonus rule to Prohibition, noting that it was “as lofty in its idealistic motivations . . . and as impractical in its application.” Daley added that the rule “didn’t work and produced more ills than it was supposed to cure.”[fn]Arthur Daley, New York Times, 4 September 1949.[/fn] Daley and others reported that just as bootleggers had circumvented Prohibition’s restrictions, owners were adept at finding ways around the bonus rule. Some of these ruses included signing prospects’ fathers to scouting contracts, paying off mortgages on prospects’ family homes, and treating prospects and their families to lavish entertainment.

Daley also noted that “bonus players, per se, breed discontent”[fn]Ibid.[/fn] and cited the situation in Boston in 1948 as the most egregious example. Johnny Antonelli, the 18-year-old who received the largest signing bonus that year, had joined the Braves in midseason, but manager Billy Southworth was unwilling to use an unproven rookie in the heat of a close pennant race. Consequently, the youngster faced only 17 batters in four innings, and his resentful teammates refused to vote him a share of the team’s World Series earnings. Following the season, Johnny Sain, whose 24–15 record earned him The Sporting News’ Pitcher of the Year honors, demanded and got a raise. Clubhouse dissention, due at least in part to resentment of the Bonus Baby, continued to plague the Braves in 1949, eventually causing Southworth to step down for the final third of the season.

When the end for the controversial bonus rule finally came in December 1950, its demise was overshadowed by a more newsworthy event: Major-league owners approved its elimination at the same meeting where they voted not to retain “Happy” Chandler as commissioner. The minor leagues ratified elimination of the bonus rule in early December, and Arthur Daley penned its obituary, concluding that “the bonus rule never did achieve its purpose. It didn’t halt extravagant spending. It retarded the development of kids it was supposed to help and in some instances ruined them. It destroyed team morale. It led to sharp practice and chicanery. It was a bad rule.”[fn]Arthur Daley, New York Times, 15 December 1950.[/fn]

Writing 22 years later, Paul Hemphill, in an article appropriately titled “Whatever Happened to What’s-His-Name?” focused on the adverse impact the rule had on the young players. He said: “Forced to sit in big league dugouts—gaining no experience, ostracized by jealous teammates, eventually the source of humor for fans and press—they waited while their potential, assuming they ever had any, stagnated and often disappeared.”[fn]Hemphill, “Whatever Happened to What’s-His-Name?”[/fn]

Apparently, the club owners did not fully share these assessments of the failure of their initial attempt to limit bonus payments. Only two years after killing the first bonus rule, they approved an even more stringent variation on the theme. In 1952, led by Branch Rickey, the owners passed a new bonus rule (Rule 3k), which lowered the bonus threshold from $6,000 to $4,000 and required that players signed for more than this amount be immediately placed on the signing team’s major-league roster for two years. This new rule, labeled “baseball’s biggest blunder” by Brent Kelly in his 1996 book of the same name, remained in effect for five seasons (1953–1957) and suffered from (and perhaps exacerbated) the shortcomings of the rule it replaced.

While this rule was in effect, every major-league team signed and carried on its roster at least one Bonus Baby. In all, 57 untried youngsters garnered this designation[fn]Steve Treder, “Cash in the Cradle: The Bonus Babies,” The Hardball Times, 11 November 2004.[/fn] and the financial rewards that accompanied it. Few of them gained the stardom that their signers envisioned, although the list does include three Hall of Famers—Al Kaline, Harmon Killebrew, and Sandy Koufax.

What happened after the rule was eliminated suggests that it did have some dampening effect on the amounts spent on bonuses. In 1958, the first year following rejection of the second bonus rule, majorleague teams paid some $6 million dollars in bonuses, compared to approximately $5 million during the preceding decade.[fn]Kelly, Baseball’s Biggest Blunder.[/fn] The owners reacted by implementing an unrestricted draft of first-year players. This concept, which had been discussed for several years but always rejected, allowed teams to draft any first-year player not protected on a major-league roster for a standard draft amount. The drafting team was then required to place the drafted player on its roster for a full year.

The first year–player draft did help to reduce the number of signing bonuses, but the amounts of these bonuses continued to creep upward. The owners tweaked the details of the first-year draft and continued to discuss (and reject) an unrestricted free-agent draft—a concept which finally earned approval in 1965 and remains in place today.

The history of baseball owners’ efforts to control the amounts paid to untried but highly touted young players suggests that there may be no ceiling on such payments and no viable way to create one. The two young Georgians who were courted in 1948 were among the first players who had to consider how bonus rules would affect them—both their immediate financial status and their long-term future. As we will see, they chose different paths and achieved different results.

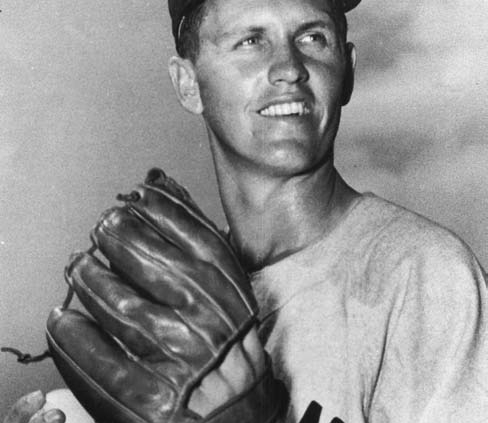

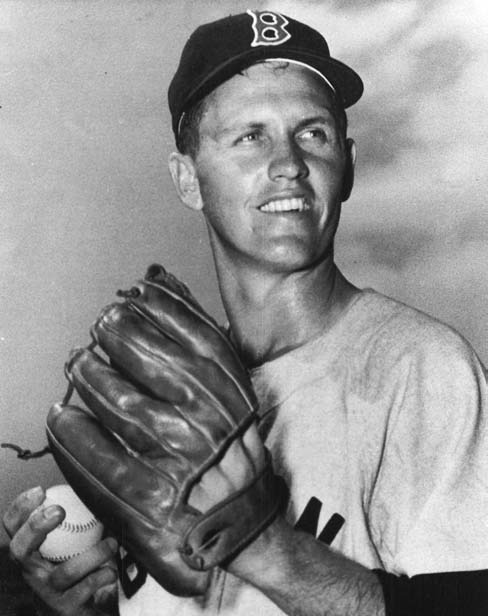

WILLARD LEE NIXON: COLLEGE MOUND ACE

Willard Nixon was the older and more experienced of the two Peach State phenoms. He was born in Taylorsville, Georgia (near Rome), in 1928 and lived in that area all of his life. By the time he graduated from high school, where he excelled in football and basketball, he was a veteran of four seasons of textile ball, first as part of an informal effort to “keep baseball alive despite wartime conditions”[fn]Langdon B. Gannon, Rome News Tribune, 22 April 1943.[/fn] and later in the Northwest Georgia Textile League (NWGTL).

Willard Nixon was the older and more experienced of the two Peach State phenoms. He was born in Taylorsville, Georgia (near Rome), in 1928 and lived in that area all of his life. By the time he graduated from high school, where he excelled in football and basketball, he was a veteran of four seasons of textile ball, first as part of an informal effort to “keep baseball alive despite wartime conditions”[fn]Langdon B. Gannon, Rome News Tribune, 22 April 1943.[/fn] and later in the Northwest Georgia Textile League (NWGTL).

Nixon’s textile-league experience was with the team representing Pepperell Mills. He played his first game in 1943 when he was only 14 and was used sparingly during that season. He pitched a two-hit, nine-inning shutout in an exhibition game early in 1944, but he fared less well against Pepperell’s regular opposition and again saw limited action during the remainder of the season. In 1945, Willard became the acknowledged “ace” of the Pepperell pitching staff. He compiled a 6–1 record and earned two complete game victories when Pepperell swept a best-of-three postseason tournament. The final victory came just two days after he had intercepted a pass and returned it for a touchdown to spark McHenry High to a 19–9 win over Trion High.

He opened the 1946 NWGTL season with three shutouts and 33 2?3 consecutive scoreless innings and compiled a regular-season record of 12–3. When Pepperell became league champions by winning two postseason series, Nixon was the workhorse—and the show horse—of both. He pitched in six of the ten games and played left field when he was not on the mound. He won the deciding game of each series and batted .519 (19 for 37) for the postseason, including a game-tying solo home run in the final game.

In 1947, the Detroit Tigers offered Willard a contract following his graduation from McHenry High, but he chose instead to accept a grant-in-aid from Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University). In his Auburn debut, Willard faced only 19 batters in five innings against Mercer University to earn his initial collegiate victory. He compiled an 8–2 season record and led Auburn to a second-place finish in the powerful Southeastern Conference.

College baseball in 1947 was a far cry from the attraction it has now become; it was then a minor sport that attracted few fans. As Nixon himself said in a 1974 interview, it “was just something students came out to watch if they didn’t have anything else to do.”[fn]Owen Davis, The Auburn Bulletin, 28 August 1974.[/fn] Willard had played before larger crowds—and perhaps faced better players—back home in the textile league. It was, however, a bigger stage, and his performance placed him in a brighter spotlight than ever before. Johnny Bradberry, sports editor of the Atlanta Constitution, reported that “folks are calling Nixon the best pitching prospect in the Southeastern Conference since Spud Chandler.”[fn]This quotation comes from an undated newspaper clipping in one of the many scrapbooks (this one labeled 1947) maintained by Mrs. Nancy Nixon, Willard’s widow. After graduating from the University of Georgia, Spurgeon Ferdinand “Spud” Chandler pitched for the New York Yankees for 11 years (1937–47), compiling a 109–43 record—the highest winning percentage for any pitcher in history with 100 or more games.[/fn]

When the collegiate season ended in May, Willard rejoined his Pepperell team, which had started its NWGTL season in April. He soon benefited from a record-setting performance by Pepperell third baseman “Shorty” Hall, who hit four home runs in four consecutive innings off four different pitchers. Pepperell (and Nixon) won that game 25–4, and Hall became the subject of a Ripley’s Believe It or Not cartoon. Willard’s 1947 NWGTL record was 8–1, and he again was the undisputed star of the postseason. He pitched in five of the six games, winning three, “saving” one, and losing one. He batted “only” .364, but three of his four hits were for extra bases, yielding a 1.000 slugging percentage.

Willard returned to Auburn and, in the Tigers’ 1948 conference opener, struck out 20 Ole Miss batters to set a new Auburn and SEC record. In his next outing, Nixon was perhaps even better. He tossed a no-hitter against the University of Tennessee, striking out 18 batters and walking four. When he next faced the Vols, only a “scratch” eighth-inning single deprived him of a second no-hitter. In that game, Nixon contributed four hits, including a 370-foot home run, and the Rome News Tribune observed that “folks in Knoxville think that [Nixon] is the greatest college player of all time.”[fn]Rome (Ga.) News Tribune, 29 April 1948.[/fn]

Others held similar opinions. Danny Doyle, his Auburn coach, called Nixon “the greatest prospect I’ve ever coached,” adding that “the team wouldn’t have been much without him.” Teammate Erskine (Erk) Russell, who later became a legendary football coach at the University of Georgia and Georgia Southern University, recalled, “I never thought about losing when Willard was pitching. He was so good that you just knew when he pitched you were going to win.”[fn]Inside the Auburn Tigers (a monthly magazine for Auburn fans), August 1983.[/fn]

Auburn won the SEC Eastern Division title, and Nixon pitched the final regular season game in front of scouts from 14 major-league teams. He finished the season with 145 strikeouts (an SEC record that would stand for 39 years) and a 10–1 record. He also led Auburn in hitting with a .448 batting average.

Every team except the Chicago White Sox and the Philadelphia Athletics bid for Nixon’s services, and two days after the season ended, he signed a contract with the Boston Red Sox. Mace Brown, in the first year of his long scouting career with the BoSox, proudly declared that Willard Nixon was “the greatest college pitcher” he had seen and predicted that “he can’t miss being a big leaguer.”[fn]Undated clipping in Nancy Nixon’s 1948 scrapbook.[/fn]

Nixon reportedly was offered bonuses of as much as $30,000, but, knowing that such a bonus would limit his time in the minor leagues, he chose to take less money. He later explained his decision, saying, “Although nobody in the world needed the money more than I did, I just didn’t think I was good enough to start at the top. I was afraid I might get that money and go up to the majors and flop. Then that bonus money might be all I’d ever get out of baseball.”[fn]Roger Birtwell, Boston Globe, 14 March 1949.[/fn]

Willard Nixon had been a successful pitcher in two different and very competitive environments, but, until he was invited to Cleveland by Lou Boudreau toward the end of his college career, he had never even seen a major-league game. He wanted to be sure that he had time to fully test his skills against other professional players before joining a major-league team. That way, he would earn his place on a major-league roster.

HUGH FRANK RADCLIFFE: SCHOOLBOY STRIKEOUT KING

Hugh Radcliffe gained national attention in April 1948, when he struck out 28 opposing batters in a nine-inning high school baseball game. Radcliffe, pitching for Robert E. Lee Institute, faced 33 Lanier High batters, who managed to make contact with only 10 of his pitches for seven foul balls, two infield grounders that his teammates booted, and the lone hit that he surrendered—another infield roller that Coach J. E. Richards said “should have been fielded, but the boys are too accustomed to watching Radcliffe play the game by himself.”[fn]Thomaston Times, 23 April 1948.[/fn] Four times, a third strike eluded the R. E. Lee catcher. Three times he was able to throw the batter out at first base, but the fourth batter reached first safely, giving Hugh the opportunity to record an “extra” strikeout to complete his one-hit, two-walk shutout of a team that had won a pennant the previous year.

Hugh Radcliffe gained national attention in April 1948, when he struck out 28 opposing batters in a nine-inning high school baseball game. Radcliffe, pitching for Robert E. Lee Institute, faced 33 Lanier High batters, who managed to make contact with only 10 of his pitches for seven foul balls, two infield grounders that his teammates booted, and the lone hit that he surrendered—another infield roller that Coach J. E. Richards said “should have been fielded, but the boys are too accustomed to watching Radcliffe play the game by himself.”[fn]Thomaston Times, 23 April 1948.[/fn] Four times, a third strike eluded the R. E. Lee catcher. Three times he was able to throw the batter out at first base, but the fourth batter reached first safely, giving Hugh the opportunity to record an “extra” strikeout to complete his one-hit, two-walk shutout of a team that had won a pennant the previous year.

Following this game, the opposing coach predicted, “Radcliffe has the physical equipment and pitching know-how to be a truly great pitcher.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn] One of the players who faced Hugh that day was Inman “Coot” Veal, who was destined for a six-year major-league career. He described Hugh’s curveball as the best he ever saw, noting that it “broke straight down at your feet.”[fn]Thomaston-Upson Sports Hall of Fame.[/fn] The Atlanta Journal waxed poetic in an editorial, gushing: “Georgia, home state of Ty Cobb and Nap Rucker, of Sherrod Smith and Carlisle Smith, of Rudy York and Johnny Mize and Spurgeon Chandler, of Luke Appling and Martin Marion and Hugh Casey, should be proud of the towering R. E. Lee Institute athlete whose feat we confidently predict will never be equaled.”[fn]Atlanta Journal, 22 April 1948. Most of the names in this list will be familiar to all baseball fans. The two Smiths are the least well known; both had long but relatively undistinguished major-league careers. Carlisle, who was better known as “Red,” was not born in Georgia, nor was Martin (Marty) Marion, who was a prep star at Atlanta’s Tech High. The Journal’s choice of players with whom to compare Radcliffe was less insightful than the prediction that the record would not fall; no one has yet matched or topped that standard.[/fn]

This record-setting game was the capstone of a youthful athletic career that had made Radcliffe a local legend in and around Thomaston, Georgia, where oldtimers still call him by his dual first names—“Hugh Frank.” He earned All-State honors in football, track, basketball, and (of course) baseball. His high-school coach called him “the best high school punter he ever saw,” and he once booted a football 78 yards in the air. He won the district pole-vaulting championship with a record jump of 11’4″ despite a sprained ankle. He was the starting guard on the R. E. Lee basketball team, and many observers believed that he had enough talent for a pro career in that sport.[fn]Ibid.[/fn] His American Legion baseball coach said, “[Hugh] can play any position on the field well; he can even catch.”[fn]Florence (S.C.) Morning News, 17 August 1946.[/fn]

This versatile athlete had first attracted the attention of professional baseball scouts in 1946, when he led Thomaston’s American Legion team to the state championship and then to the regional crown before losing to New Orleans, the eventual national champion, in the sectional playoffs. These sectional games attracted as many as five thousand fans, giving Hugh and his teammates their first experience playing before such large crowds.

Radcliffe finished his senior year at R. E. Lee with 210 strikeouts in 81 2?3 innings—an average of 2.6 strikeouts per inning. He tossed two seven-inning no-hitters, and in his three nine-inning games, he averaged 24+ strikeouts and threw two one-hitters. He allowed only 16 hits and three earned runs for the season while compiling a 9–0 record.[fn]Hagerstown (Md.) Daily Mail, 4 June 1948.[/fn] He accomplished all this with a pitching arsenal that included a 95 mph fastball, a “diving” sinker, and two different curve balls—a “wide-sweeping” one and the overhand “bottomless” version that Coot Veal described.[fn]Thomaston-Upson Sports Hall of Fame.[/fn]

Hugh led his team into the state championship tournament, where on June 2 (one day after graduating) he pitched his last high-school game. He went the full nine innings and struck out 24 batters, matching his season average, but R. E. Lee made nine errors and lost 8–6. The next day, after considering offers from 14 major-league scouts (including Branch Rickey himself and fellow Georgian Spud Chandler), Hugh Radcliffe accepted a $40,000 bonus from the Philadelphia Phillies. A rival scout reported later that Johnny Nee, the Phillie scout who won the “Radcliffe Sweepstakes,” had “told everybody he had no limit. His club . . . told him to sign Radcliffe and to go as high as he had to to get him.”[fn]Wayne Minshew, “Scouting Big League Talent Has Changed with the Years” Baseball Digest, July 1976.[/fn]

According to the local paper in an article looking back at Radcliffe’s career, the youngster “was just as eager as any teen-ager to get to the top as fast as possible, particularly on an ‘earn as you learn’ basis.”[fn]Thomaston Times, 17 June 1955.[/fn] He had had no more exposure to major-league baseball than the slightly older Nixon, but with the unbridled confidence of youth he must have been sure that he had the talent needed to succeed. He had achieved amazing things on the diamond, and a bevy of experienced baseball men were bidding for his services. Surely, their expectations were reasonable. How could he turn down that kind of money?

NIXON AND RADCLIFFE: PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL CAREERS

Immediately after signing professional contracts, the two young Georgians were sent north to join minorleague teams. Nixon went to the Scranton (Pennsylvania) Red Sox in the Class A Eastern League, and Radcliffe reported to the Wilmington (Delaware) Blue Rocks in the Class B Interstate League. He arrived the same day that fellow “Bonus Baby” Robin Roberts was promoted to the major-league club.[fn]Doug Gelbert, The Great Delaware Sports Book (Montchanin, Del.: Manatee Books, 1995).[/fn]

Radcliffe left his first start in the seventh inning, trailing 5–0, but went on to compile a respectable 7–3 record. Nixon’s debut, one day before his twentieth birthday, was more impressive. He struck out the first batter he faced and pitched an eight-hit shutout against the Wilkes-Barre Barons. Local sportswriter Chic Feldman exclaimed that “the door to a glittering future opened at the stadium last night and in strode Willard Nixon, blond and beautiful (both physically and baseballically).”[fn]Chic Feldman, Scranton Tribune, 17 June 1948.[/fn] He closed the regular season with five consecutive victories to end the season with an 11–5 mark, and his final victory clinched the league championship for Scranton. His final game came in the postseason, and it was a “masterful two hitter”[fn]Chic Feldman, Scranton Tribune, 22 September 1948.[/fn] in frigid weather.

Despite his winning record and acceptable ERA (4.12), the Phillies did not put Radcliffe on the major league roster at the end of the season. Sportswriter Jeff Moshier speculated that the “Phillies already were overburdened with bonus men.”[fn]Jeff Moshier, Saint Petersburg Independent, 22 November 1949.[/fn] Perhaps the major league decision makers also were concerned about Hugh’s control problems; he walked 82 batters in 92 innings. Whatever the reasoning, Hugh Radcliffe was still in the minor leagues at the end of the 1948 season, making him available to be drafted by other teams. He was among “the most publicized and highest paid” of the 270 “bonus tag” players whom big-league clubs left exposed to the draft in 1948,[fn]Saint Petersburg Times, 9 November 1948.[/fn] but there were no takers.

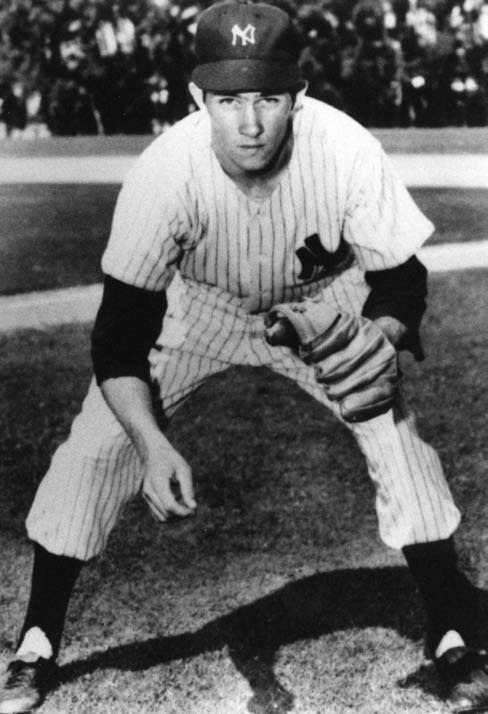

Both Nixon and Radcliffe started their sophomore seasons at the triple-A level. Nixon was assigned to the Louisville Colonels of the American Association; the Phils sent Radcliffe to the Toronto Maple Leafs in the International League. Neither of the youngsters fared well at that level. Nixon recorded three losses and a “no decision” in four games for Louisville and was demoted to the Birmingham Barons in the double-A Southern Association. Radcliffe saw limited duty in Toronto, appearing in only nine games and compiling a 1–1 record and a 1.91 WHIP in a mere 22 innings. The Phils’ brass said that injuries prevented Hugh from playing more, but others accused them of using the youngster sparingly “in hopes that he would escape the draft.”[fn]Jeff Moshier, Saint Petersburg Independent, 22 November 1949.[/fn] If that were their plan, it did not work; the New York Yankees drafted Hugh Radcliffe in November.

After being reassigned to double-A ball and following a slow start at that level, Willard Nixon had an outstanding 1949 season. He lost his first three games for the Barons, making him 0–6 for the season, but he then won 14 of his final 18 decisions to finish the regular Southern Association season at 14–7, and at least two of his losses were due to poor defensive support. A local sportswriter described his pitching as “phenomenal after a shaky start.”[fn]Naylor Stone, Birmingham Post, 13 September 1949.[/fn] He also had the highest batting average (.345) on the team.

The highlight of the 1949 season for Willard Nixon came on Monday, August 15, at Ponce de Leon Park in Atlanta. With a large contingent of fans from his home town among the 4,996 in the stands and even more watching the game on television at the American Legion clubhouse in Lindale, Willard dominated the Atlanta Crackers. The final score was 5–4, and Nixon had pitched all nine innings and driven in all five Baron runs. As Langdon B. Gammon reported: “He was the whole show, producer and star.”[fn]Langdon B. Gammon, “Lindale News,” Rome News Tribune, 15 August 1949.[/fn]

Two years after making their decisions regarding immediate riches versus the potential for delayed gratification, the two young pitching prospects from Georgia each had experienced some success and some tribulation. Neither was yet in the major leagues, but one remained with his original suitor, while the other was facing an uncertain future with a new organization.

After facing major-league hitters during spring training, both players started the 1950 season at Triple A. Nixon went back to Louisville, and the Yankees assigned Radcliffe to the Kansas City Blues. At the time, Casey Stengel said that both he and young Eddie Ford had “excellent prospects of climbing back fast.”[fn]New York Times, 30 March 1950. Eddie Ford, better known as “Whitey,” climbed back and began his Hall of Fame career on July 1.[/fn]

Although both Georgia youngsters were now in the American Association, they did not face off as mound opponents. The junior Georgian pitched in only two innings in two games for the Blues, compiling a losing record (0–1) and a WHIP of 4.00. On May 6, he was reassigned to Binghamton in the Class A Eastern League, three days before Nixon faced Kansas City for the first time. Hugh prospered a bit in the lower classification, appearing in 25 games and managing a winning record (9–8), although his ERA (4.14) and his WHIP (1.71) remained high.

While Radcliffe’s triple-A performance earned him a demotion, Nixon proved that his earlier difficulties at that level were a clear case of premature promotion. This time around, he got off to a fast start, winning his first three games. On July 2, he won his sixth consecutive game, bringing his record to 11–2. On July 6, he was promoted to the parent club. His 97 strikeouts led the American Association, and he was batting .345. Just over two years after signing with the Red Sox, Willard Nixon had gotten the minor-league seasoning that he thought he needed. He joined the Big Sox in New York and received his major-league baptism immediately. On July 7, he pitched the last two innings of a 5–2 Red Sox loss to the Yankees. He allowed one run on three hits, walked three batters, and struck out none—not especially impressive, but manager Steve O’Neill was happy with the results. He noted that Nixon “fired the ball hard and had those Yankees refraining from taking toe holds.”[fn]Arthur Sampson, Boston Traveler, 13 July 1950.[/fn] By season’s end, Willard had appeared in 22 games and compiled a winning (8–6) record.

Willard Nixon was in the big leagues to stay. He spent the next eight years with the Red Sox, although he never achieved the stardom that many baseball experts continued to predict for him. Early in his career, he struggled to control his pitches and his temper; later, he often pitched despite a painful shoulder. His best two years came in 1954–1955, when his overall 23–22 record was overshadowed by his mastery over the powerful New York Yankees, which earned him a spot on the cover of The Sporting News [fn]The Sporting News, 4 May 1955.[/fn] and the nickname of “Yankee Killer.” He beat the Yankees four consecutive times in 1954, yielding no more than one earned run in any game, and he won his first two games against them in 1955—a streak of six straight wins over the Bronx Bombers. Although his dominance over the Yankees did not continue and while he was not as successful against many of his lesser opponents, Willard would have finished his career with an overall winning record had he not tried to pitch through arm trouble in 1958. He compiled a woeful 1–7 record that year, dropping his career record to 69–72. He returned to the minors in 1959 with the triple-A Minneapolis Millers in an attempt to “pitch [his] way back to the majors,”[fn]Tom Briere, Minneapolis Tribune, 12 April 1959.[/fn] but after nine seasons in the majors, his big-league career was over.[fn]Thirty other American League pitchers made their major–league debut in the same year as Nixon, and only three (Lew Burdette, Whitey Ford, and Ray Herbert) pitched longer and won more games. Two fellow 1950 Red Sox rookie pitchers (Dick Littlefield and Jim McDonald) equaled his longevity, but neither matched his record. The average career for 1950’s other 25 American League rookie pitchers was 3.6 years.[/fn]

Hugh Radcliffe, by contrast, was destined to be a career minor leaguer. Following his winning 1950 season in Binghamton, the Yankees gave him a contract for another year, and he joined the team in Phoenix [fn]This is the only time that the Yankees have gone west for spring training. Yankees co-owner Del Webb, a resident of Phoenix, swapped training sites with the New York Giants, who came east to use the Yankees’ usual site in St. Petersburg, Florida.[/fn] for spring training. After a successful start in an intrasquad game,[fn]In an interview on October 21, 2009, Radcliffe recalled that he pitched the first five innings of a game that pitted the Yankees rookies against each other and gave up only one hit—a triple to Mickey Mantle, who was experiencing his first spring training.[/fn] he struggled and was farmed out to Kansas City after giving up seven runs to Cleveland in a two-inning outing that included five walks and a wild pitch. He spent only a month in Kansas City, appearing in three games and compiling a 1–0 record, before being assigned to Beaumont in the double-A Texas League, where he won six, lost eight, and amassed a 1.74 WHIP. In September, he was one of 12 minor leaguers “recalled” by the Yankees but not asked to report immediately. In January 1952, the Yankees announced his “outright release,” leading the New York Times to say it was “the end of the trail” for “bonus baby” Hugh Radcliffe.[fn]New York Times, 31 January 1952.[/fn]

This pronouncement proved to be premature, as Hugh signed on with Kansas City. He did not play for the Blues, however. He was assigned and reassigned three times, opening the 1952 season back in Beaumont, spending six weeks with the Tyler East Texans[fn]On July 15, 1952, Hugh Radcliffe participated (as a pinch-runner) in a 20-inning Tyler loss (3–2) to the Texarkana Bears.[/fn] of the Class B Big State League, and then going back to Class A Binghamton for the last month of the season. Hugh was taking the “journeyman ballplayer” appellation literally: his travels took him to three teams at three different classifications, for a combined record of 9–7 and WHIP of 1.54. Following the season, Hugh said that he had asked the Beaumont club to send him to a team where he could be part of the regular rotation. He added that he had learned more in the last half of the season than in four years of professional baseball, having “turned from a thrower to a pitcher.”[fn]Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 21 November 1952.[/fn] He admitted later, however, that while with this club, he suffered the injury that effectively ended his hopes of a big-league career. He said that he had been put into a game on a chilly night without proper warmup, and his arm “went bad” and was never the same.[fn]Thomaston Times, 17 June 1955.[/fn] He was still the property of the Kansas City club and was eligible for the draft, but only a major-league team could claim him; none did.

Before he threw a pitch in 1953, Hugh Radcliffe had been the property of four minor-league clubs—Kansas City, Birmingham (Double A, Southern League), Syracuse (Triple A, International League), and Natchez (Class C, Cotton States League). With this last club, Hugh saw more action than in any of his other minorleague seasons. He appeared in 33 games, winning 13 and losing an equal number. His ERA was 3.74, and his WHIP was 1.51. At the end of the season, Birmingham reclaimed and reserved his rights.

Birmingham assigned Hugh to Winston-Salem (Class B, Carolina League) before the 1954 season started. He appeared in only three games, losing his only decision, before being returned to the Barons on May 1. Four days later, the Barons released him, and his trail truly came to an end. The $40,000 bonus baby had spent seven years in the minor leagues, playing for eight different teams in eight different leagues at every minor-league classification above Class D. He had managed an overall winning record (46–42) although with only two winning seasons. He had constantly struggled with his control, averaging 6+ walks per nine innings pitched over his career.

Both these Peach State natives expressed some regrets as they looked back over their professional baseball careers. For obvious reasons, Nixon’s regrets were fewer. He summed up his playing days by saying, “I didn’t get the most out of my ability, but I’m happy with [my career]. Baseball’s been good to me. I wouldn’t have had anything if it hadn’t been for baseball.”[fn]Undated article in Nancy Nixon’s scrapbook.[/fn] Radcliffe openly rued his decision regarding the bonus money. In 1955, the year after his career ended, he said: “If I had it to do over, I wouldn’t be a bonus boy. They bring the bonus boys up too fast and they don’t get the chance that some of the other players get. If I had had a chance to come up a little slower, and had had a little time to spend with a few pitching coaches, I think I’d be up there winning today.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn] In his later years, Hugh Frank was more philosophical; looking back in 2009, he said, “I’m kinda glad I didn’t make it. I would have had to raise my family up there and wouldn’t have gotten to spend as much time with them.”[fn]Interview with Hugh Frank Radcliffe, 21 October 2009.[/fn]

LIFE AFTER BASEBALL

Both Willard Nixon and Hugh Frank Radcliffe had long, productive lives after their baseball days had ended. Both found careers beyond the ballpark. Both raised families. Both found pleasure in active hobbies. Both retained legendary status in their hometowns. As with their baseball careers, they took somewhat different paths, but now the results were much more similar.

The first year of professional baseball was the last year of bachelorhood for both young men, and they found lifelong partners. Willard and Nancy Nixon had been married for more than 51 years when he passed away in 2000; together they raised three children. Hugh and Marge Radcliffe have now been married for more than 60 years and have raised four children.[fn]Ibid. Hugh said that he named one of his sons “Rip” after Raymond Allen (Rip) Radcliff, who had a 10-year major-league career (1934–43). He mistakenly thought they shared a common spelling of their last names.[/fn]

| WILLARD NIXON | HUGH RADCLIFFE | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Team | League | G | IP | W-L | ERA | Team | League | G | IP | W-L | ERA | |

| 1948 | Scranton | EL (A) | 18 | 132.0 | 11–5 | 2.52 | Wilmington | ISL (B) | 16 | 96.0 | 7–3 | 4.12 | |

| 1949 | Louisville | AA (AAA) | 4 | 23.0 | 0–3 | 5.09 | Toronto | IL (AAA) | 9 | 22.0 | 1–1 | INA | |

| Birmingham | SA (AA) | 22 | 177.0 | 14-7 | 3.41 | ||||||||

| 1950 | Louisville | AA (AAA) | 13 | 117.0 | 11–2 | 2.69 | Kansas City | AA (AAA) | 2 | 2.0 | 0–1 | 18.00 | |

| BOSTON | AMERICAN | 22 | 101.3 | 8–6 | 6.04 | Binghamton | EL (A) | 25 | 150.0 | 9–8 | 4.14 | ||

| 1951 | BOSTON | AMERICAN | 33 | 125.0 | 7–4 | 4.90 | Kansas City | AA (AAA) | 3 | 11.0 | 1–0 | 3.27 | |

| Beaumont | TL (AA) | 22 | 113.0 | 6–8 | 3.90 | ||||||||

| 1952 | BOSTON | AMERICAN | 23 | 103.7 | 5–4 | 4.86 | Beaumont | TL (AA) | 10 | 52.0 | 1–3 | 3.63 | |

| Tyler | BSL (B) | 8 | 45.0 | 3–2 | 4.60 | ||||||||

| Binghamton | EL (A) | 9 | 56.0 | 5–2 | 3.54 | ||||||||

| 1953 | BOSTON | AMERICAN | 23 | 116.7 | 4–8 | 3.93 | Natchez | CSL (C) | 33 | 183.0 | 13–13 | 3.74 | |

| 1954 | BOSTON | AMERICAN | 31 | 199.7 | 11–12 | 4.06 | Winston-Salem | CL (B) | 3 | INA | 0–1 | INA | |

| 1955 | BOSTON | AMERICAN | 31 | 208.0 | 12–10 | 4.07 | |||||||

| 1956 | BOSTON | AMERICAN | 23 | 145.3 | 9–8 | 4.21 | |||||||

| 1957 | BOSTON | AMERICAN | 29 | 191.0 | 12–13 | 3.68 | |||||||

| 1958 | BOSTON | AMERICAN | 10 | 43.3 | 1–7 | 6.02 | |||||||

| 1959 | Minneapolis | AA (AAA) | 26 | 98.0 | 6–2 | 3.58 | |||||||

| Minor-League Totals (4) | 83 | 547.0 | 42–19 | 3.14 | Minor-League Totals (7) | 140 | 730.0 | 46–42 | 3.85 | ||||

| Major-League Totals (9) | 225 | 1234.0 | 69–72 | 4.39 | Major-League Totals (0) | 0 | 0.0 | NA | NA |

Even before he retired, Nixon became one of the most popular and successful amateur golfers in Northwest Georgia and maintained this status until failing health forced him off the links. Radcliffe also became an avid golfer and fisherman and retired to Florida so that he could pursue both hobbies, which he is again enjoying after recovering from a bout with cancer.[fn]Ibid.[/fn] Hugh’s decision to retire to Florida reflects another major difference in the lives of these two Georgians. Willard Nixon arranged his life so that he never lived more than 10 miles from his birthplace; Hugh Radcliffe never lived in Thomaston after he graduated from high school, although he did return often to visit family members[fn]Hugh came from a large family. He had ten siblings, and one of them did make it to the major leagues. His older sister, Emma Lou Radcliffe Boss (1922–2007), spent 17 years as an administrative assistant to Hank Aaron and the Atlanta Braves.[/fn] and to participate in ceremonies honoring his accomplishments.

In 2004, Hugh Frank Radcliffe was among the first 15 athletes inducted into the Thomaston–Upson County Sports Hall of Fame. Willard Nixon had received a similar honor in 1971, when the Rome–Floyd County Sports Hall of Fame inducted its inaugural class of seven. Nixon was also elected to the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame in 1993. That honor has so far eluded Radcliffe, but in 1998, the Georgia House of Representatives passed a resolution commending his athletic achievements in four sports and especially honoring “the golden day he struck out 28 batters.”[fn]Georgia House of Representatives, HR 1258.[/fn] Radcliffe’s most recent honor came in 2008, when the clubhouse at Thomaston’s Silvertown Ballpark (the site of his historic performance) was named in his honor.

HUGH RADCLIFFE: POSTER BOY FOR THE EVILS OF THE BONUS RULE—OR NOT?

The two heroes of this story faced similar situations, made very different decisions, and achieved very different results. The intriguing question is the degree to which their decisions to accept or reject large bonuses impacted their upward mobility.

Willard Nixon thought he needed minor-league experience before he would be ready to pitch in the majors. In two and a half years, he got that experience, moving smoothly through Classes A, AA, and AAA. His only slip during that climb came when he was promoted from Class A to Triple A before he was ready. When he faltered at the higher level, he went to Double A and pitched well.

In contrast, after the pitching-rich Phils chose not to protect their investment in Hugh Radcliffe by adding him to the big-league roster, they promoted him all the way to triple-A Toronto to ensure that only another major-league team could draft him. He had been somewhat successful in Class B, but he skipped Class A and AA and spent his entire sophomore year at the triple-A level, getting little opportunity to prove himself there.

Radcliffe’s belief that he would have done better if he had rejected the bonus offer, of course, echoes the concerns voiced by opponents of the bonus rule, but can we be sure that his “bonus boy” status is what prevented him from becoming a major leaguer? In spite of a reasonably successful first season, no other major-league club saw enough potential to add him to their roster after the Phillies exposed him to the draft. If his limited use at Toronto was truly a ruse to keep other teams from noticing him, then his bonus status certainly retarded his progress. If he was kept at the triple-A level to reduce the number of teams who could draft him, his bonus status hurt him further. Radcliffe himself believes to this day that the Phillies “tried to hide me.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn] If such were not the case, there seems to be little justification for not using him more in 1949, either in Toronto or at a lower minor-league classification.

There is little doubt, therefore, that Hugh Radcliffe’s development suffered because he was a bonus baby, but other factors may have kept him in the minors while his fellow Georgian advanced to the majors. Radcliffe had the disadvantage of being selected by teams that had an abundance of pitchers. The Phillies had signed a bevy of bonus-level pitchers and reaped the benefits in 1950 when the “Whiz Kids” won the National League pennant behind the starting pitching of three Bonus Babies—Curt Simmons, Robin Roberts, and Bob Miller. The Yankees of the early 1950s dominated the American League, winning five consecutive pennants between 1949 and 1953, with a pitching staff built around Vic Raschi, Allie Reynolds, Eddie Lopat, and (later) Johnny Sain and Whitey Ford.

While he got less minor-league training than Nixon, Radcliffe probably needed it more. He had pitched extremely well, but typically against players younger than he was. During the summer between his junior and senior years in high school, Hugh did pitch for Swainsboro in the semipro Ogeechee League,[fn]62. The Ogeechee League, which derived its name from Georgia’s Ogeechee River, operated in middle and southern Georgia during the 1940s and 1950s. Teams represented small towns such as Glenville, Greenwood, Louisville, Metter, Millen, Statesboro, Swainsboro, Sylvania, Thomson, and Wrightsville. According to an article (23 April 2009) in the multititled Louisville News and Farmer & Wadley Herald & Jefferson (County) Reporter, the Louisville team bore the name “Mudcats” long before Columbus’s Southern League team adopted that nickname and retained it even after moving to North Carolina.[/fn] where most of his opponents had played college ball. He also pitched “a few games” for the local textilemill teams,[fn]Interview with Hugh Frank Radcliffe, October 21, 2009.[/fn] but he was 19 years old throughout his dominant final year in high school; most high-school seniors are a year younger than that. In contrast, Willard Nixon had pitched extensively in the textile leagues against men who were five to ten years his senior, and he had prospered against that competition.

Both players suffered from sore arms during their careers, but here again there was an important difference. Nixon hurt his arm after proving that he could pitch at the major-league level. Radcliffe’s injury came while he was struggling in the minors, effectively sidetracking any hope that he could succeed in the majors.

There seems to be little doubt that the 1948 bonus rule played a role in Hugh Frank Radcliffe’s failure to reach the major leagues. The Phillies certainly got little (if any) benefit from their $40,000 investment. There is some irony in the fact that the younger of the two players we have considered, the one who was perhaps most in need of minor-league seasoning, opted for the route that made such seasoning least likely. Yet he got minor-league experience anyway, although perhaps not in the proper sequence. Other factors also helped to keep the youngster in the minors, so the overarching lesson here may be that paying large sums for “can’t miss” (but untried) pitchers was just as risky in 1948 as it is today—and as it will likely be in 2048.

WYNN MONTGOMERY, author of the biography of Willard Nixon for SABR’s BioProject, has seen ballgames in every major league city except Arlington, Texas, and in almost fifty minor-league parks. He is coeditor, with Ken Fenster, of The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State, the 2010 SABR convention journal.

Sources

My most valuable resource for the portion of this article dealing with Willard Nixon was Mrs. Nancy Nixon, who freely shared with me her memories and her extensive collection of scrapbooks (one for almost every year he played, 1945–59) and related materials that chronicled her husband’s career. Several unattributed quotations were found in unlabeled articles in those scrapbooks. Hugh Frank Radcliffe himself graciously participated in a telephone interview and shared his memories with me, as did his long-time friends Jim Fowler and Charles Gordy. Steve Densa, Minor League Baseball’s media relations director, provided Radcliffe’s “player record card.” In addition to these resources and the specific publications cited above, the following additional sources were invaluable during the preparation of this article.

Libraries (Newspaper Archives and Staff) and Organizations

- Auburn University Library (especially Joyce Hicks)

- Boston Public Library

- Rome/Floyd County Public Library (especially Dawn Hampton)

- Upson Historical Society (specifically Penny Cliff and Patty Morgan)

Online

- Baseball Reference www.baseball-reference.com

- Newspaper Archive www.newspaperarchive.com

- New York Times www.nytimes.com

- Paper of Record http://sabr.org/paperofrecord

- Retrosheet www.retrosheet.org, for box scores and play-by-play descriptions

- SABR research tools www.sabr.org