In Memoriam: Willie Mays

The actress and noted Giants baseball fan Tallulah Bankhead once said, “There have only been two geniuses in the world – Willie Mays and Will Shakespeare.”

In baseball’s never-ending attempts to somehow order its gods, Willie Mays is the only contender whose proponents rarely use statistics to make their case. It is as if Mays’ 660 home runs and 3,293 hits somehow sell the man short, that his wonderful playing record is almost beside the point, as John Saccoman writes in his SABR biography of the “Say Hey Kid.”

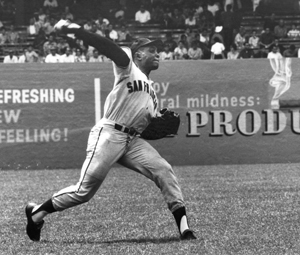

With Mays it is not merely what he did – but how he did it. He scored more than 2,000 runs, nearly all of them, it would seem, after losing his cap flying around third base. He is credited with more than 7,000 outfield putouts, many exciting, some spectacular, a few breathtaking. How do you measure that? An artist and a genius, for most of his quarter-century in the major leagues, you simply could not keep your eyes off Willie Mays.

Mays died at the age of 93 on June 18, 2024, just two days before his San Francisco Giants were scheduled to play a major-league game at Rickwood Field in Mays’ home state of Alabama. The game was designed to be a tribute to the Negro Leagues, where Mays got his start as a teenager with the Birmingham Black Barons.

Willie Howard Mays Jr. was born on May 6, 1931, the son of a talented semipro ballplayer who reportedly put a baseball in the youngster’s crib. At the age of 16, Mays signed his first professional contract with the Chattanooga Choo-Choos, a farm club to the Black Barons. He was promoted to the Negro American League in 1948 and helped Birmingham win the pennant. In the final Negro League World Series, Mays’s walk-off single won Game Three against the Homestead Grays.

After two more seasons with the Black Barons, Mays was signed by the New York Giants. Scout Ed Montague said, “This was the greatest young player I had ever seen in my life or my scouting career.”

Mays was part of an early wave of African American players who fought through bigotry following decades of segregation in professional baseball. He made his National League debut in 1951, just a few years after the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s shameful color line. His first NL hit was a towering home run off future Hall of Fame pitcher Warren Spahn. He won Rookie of the Year honors and had a front-row seat for the Giants’ historic run to the World Series.

Mays was drafted into the US Army in 1952 and lost most of the next two seasons for military service. But he picked up right where he left off when he returned to the Giants in 1954, leading New York to a World Series championship on the strength of “The Catch,” arguably the most famous play in the history of the fall classic. As Mark Simon writes, Mays’s unparalleled standard of defensive excellence made his memorable catch and throw from deep center field at the Polo Grounds almost seem routine.

Mays won the first of his two NL Most Valuable Player awards in 1954 and also made his first of a record-setting 24 All-Star teams. The Gold Glove Awards hadn’t been created by Rawlings yet, but once they were in 1957, Mays won 12 in a row, more than any other outfielder ever has.

The Giants moved to San Francisco in 1958 and Mays built a new legion of fans on the West Coast, teaming up with future Hall of Famers Willie McCovey, Orlando Cepeda, and Juan Marichal to contend for the NL pennant nearly every year. Mays continued surpassing milestones, recording a four-home run game in 1961, smashing his 600th career home run in 1969, and joining the 3,000-hit club in 1970.

In 1972, Mays returned to New York when he was traded to the Mets, who later honored him by retiring his number 24. With the Mets, Mays was a veteran presence who homered in his first at-bat with the team and helped inspire them to a surprising National League pennant.

In retirement, Mays worked first for the Mets and then the Giants as a team ambassador and “goodwill” coach. He was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979. He also mentored future stars like his godson Barry Bonds — the son of his former teammate Bobby Bonds — and Ken Griffey Jr.

At his induction ceremony in Cooperstown, Mays was humble and eloquent, saying, “This country is made up of a great many things. You can grow up to be what you want. I chose baseball, and I loved every minute of it.”

(Photos: SABR-Rucker Archive, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Related links:

- Read Willie Mays’s SABR biography, by John Saccoman

- Read essays from Willie Mays: Five Tools in the SABR Research Collection

- Read about Willie Mays’ greatest games at the SABR Games Project

Originally published: June 18, 2024. Last Updated: June 18, 2024.