Ed Williamson grave marker dedication ceremony held in Chicago

The SABR 19th Century Grave Marker Project completed its latest grave marker installation on Saturday, November 6, 2021, a dedication ceremony at Chicago’s Rosehill Cemetery to honor 19th-century home run king Ed Williamson.

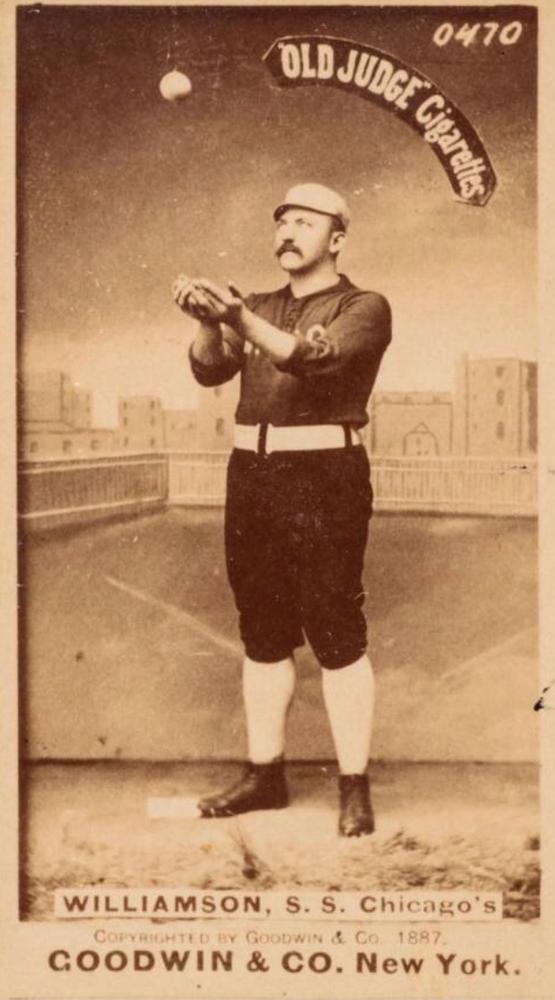

Edward Nagle “Ned” Williamson was a talented and powerful third baseman during the 1880s for the Chicago White Stockings, now known as the Cubs. In 1883 the team moved into a new ballpark near the shore of Lake Michigan. Due to the park’s unusual dimensions — the distance to the right and left field foul lines was less than 200 feet — balls hit over the fence were considered ground-rule doubles. Williamson promptly set a new National League record with 49 doubles. In 1884, those balls were allowed to be home runs and Williamson slugged a record-setting 27 homers. It was the most home runs ever hit by a National League ballplayer in the 19th century and was the major-league single-season record for 25 years, until Babe Ruth hit 29 homers in 1919.

Ed Williamson died on March 3, 1894, at the age of 36. He was buried in Chicago’s Rosehill Cemetery, and his grave remained unmarked for more than a century.

A sizable crowd of baseball historians, Cubs fans and even a few token White Sox fans showed up on November 6 to pay their respects. As project chair, I welcomed the crowd and gave a few introductory remarks before turning it over to Dave Stevens, a historian and author, who spoke about Williamson and his friendship with fellow ballplayer John Montgomery Ward. Dave wrote an article about Ed for a 2001 SABR publication, called “The Home Run King without a Headstone.” He was happy that, two decades after the article was published, we finally ruined his great headline.

Chicago SABR Vice-Chair Richard Smiley gave an excellent, compelling story about Ed’s life and career. He mentioned that many of Ed’s contemporaries called him the best all-around baseball player they ever saw. It’s an accurate description, too. Ed wasn’t the best at any one particular aspect of baseball — though you could make the argument that he was the best defensive third baseman of his era. What he did do was be very good at every aspect of the game. He was a good hitter, he had patience at the plate, and he could hit for power — regardless of the dimensions of his home ballpark. He was an outstanding fielder and had a cannon for an arm. In spite of his size, he was a good baserunner too. And he could play practically any position on the field. His versatility was invaluable, and though he was sometimes overshadowed by the Hall of Famers and other superstars who were on his Chicago White Stockings teams of the 1880s, he was a key part of one of baseball’s first great dynasties.

I thanked a few people in my opening remarks, and I would like to repeat those thank-yous now. This was my first time taking the lead for a grave marker project, and the one thing I came away with is that it’s much easier to do it when you have a good team. Thank you to the other members of the project: Ralph Carhart, John Thorn, Peter Mancuso and Bob Bailey. Since I first started doing the detective work into Ed Williamson’s whereabouts and later became chair of the Project, they have all given me good advice, words of encouragement and valuable resources.

Ralph, as the past chair of the committee, walked me through all the details and steps when I didn’t know what I was doing. It’s a privilege to associate with some of great experts and good people.Thank you to my new friends in the SABR Chicago chapter, especially Bill Pearch and Richard Smiley. They enthusiastically jumped into this project and helped create a very successful dedication. Thank you to everyone at SABR HQ who helped promote this event, and the writers like Jordan Bastian and Tony Andracki who boosted the signal as well.

Thank you to David Stalker, who made a beautiful grave marker for Ed, as he has done for all the other markers that the Grave Marker Project has placed. Thank you to the Chicago Cubs, who expressed gratitude and interest in what we do. It’s wonderful to see a major-league team be so aware of and appreciate its own history.

Thanks to @sabr’s 19th Century Grave Marker Project for dedicating a gravestone to Edward “Ned” Williamson!

Williamson played 11 seasons for the Chicago White Stockings. He died in 1894 and was buried in an unmarked grave at Rosehill Cemetery. https://t.co/67tn6huEGh pic.twitter.com/KNL2IPhy10

— Chicago Cubs (@Cubs) November 7, 2021

Lastly, thank you to the staff of Rosehill Cemetery, particularly my contact Diedre. This would have all come to a screeching halt if the cemetery had refused our request or been unwilling to search its records. Instead, Diedre went into the cemetery archives to pore over the original internment records, eventually locating Ed’s present location. Rosehill is a beautiful cemetery, and its grounds hold the final resting places of captains of Chicago industry, mayors, aldermen, a vice president, Civil War veterans and other war heroes, actors and — this being Chicago — gangsters.

There’s a strong baseball connection there as well, as it’s the final resting place of Jack Brickhouse, Jerome Holtzman, participants in the Black Sox Scandal, and several other ballplayers as well. Some are marked, some are not. For those who wish to pay their respects, Ed Williamson is easy to find in Section 6, by the fence on Peterson Avenue.

The 19th Century Grave Marker Project identifies 19th-century baseball notables who either lack a grave marker or whose headstone is in dire disrepair, and then rectify those issues. Since 2016, the project has placed grave markers for baseball pioneers James Whyte Davis and Hicks Hayhurst, and players Andy Leonard, Pud Galvin, and Bob Caruthers. Its most recent project was a grave marker for Luis Castro, the first Latin-American ballplayer to play in the major leagues.

- Video: Click here to watch highlights from the dedication ceremony on Facebook (SABR Emil Rothe Chicago Chapter)

- Photos: View more photos of the dedication ceremony at RIPBaseball.com

- Related link: Click here to learn more about the 19th Century Grave Marker Project

Originally published: October 28, 2021. Last Updated: November 8, 2021.