Joseph Creamer

Prior to his untimely death in July 1918, Dr. Joseph Creamer did much good in his life, being especially revered for his longtime free medical care of East Side Manhattan indigents. But Creamer’s virtues were interred with him. To the extent that he is remembered at all today, it is for a single, regrettable act committed as team physician for the 1908 New York Giants: an attempt to bribe the umpires prior to the playing of the pennant-deciding Giants-Cubs contest, a do-over game necessitated by Merkle’s Boner several weeks earlier. Although Creamer was plainly acting as someone else’s agent, little effort was devoted to identifying who was behind the bribe effort. Rather, the team physician was designated the affair’s fall guy, banned for life from entering a major-league ballpark by the National Commission. Shortly thereafter, the bribery inquiry was closed by officialdom, with no further action taken.

Prior to his untimely death in July 1918, Dr. Joseph Creamer did much good in his life, being especially revered for his longtime free medical care of East Side Manhattan indigents. But Creamer’s virtues were interred with him. To the extent that he is remembered at all today, it is for a single, regrettable act committed as team physician for the 1908 New York Giants: an attempt to bribe the umpires prior to the playing of the pennant-deciding Giants-Cubs contest, a do-over game necessitated by Merkle’s Boner several weeks earlier. Although Creamer was plainly acting as someone else’s agent, little effort was devoted to identifying who was behind the bribe effort. Rather, the team physician was designated the affair’s fall guy, banned for life from entering a major-league ballpark by the National Commission. Shortly thereafter, the bribery inquiry was closed by officialdom, with no further action taken.

In recent years, the Creamer bribe attempt has been revisited by baseball authors chronicling the tumultuous 1908 season. David W. Anderson and Cait Murphy, but particularly Angelo J. Louisa and Floyd Sullivan, have applied much-needed, but ultimately inconclusive, forensic analysis to the largely forgotten scandal. Virtually no attention in these decades-later post-mortems, however, is paid to the life of Dr. Creamer, the officially designated villain. This profile endeavors to fill that void.

Joseph Marie Creamer III was a man with distinguished bloodlines. His family tree was populated by generations of physicians, attorneys, and government officials, both in the Canadian Maritime Provinces and Brooklyn. He was born on September 21, 1876, in Charlottetown, the capital of Prince Edward Island, Canada, the oldest of three children born to Joseph Marie Creamer Jr. (1852-1900) and his wife, the former Catherine Reddin (c. 1857-1934).1 The children’s maternal grandfather was Dennis O’Meara Reddin, a distinguished attorney and the first Roman Catholic appointed to the high-court bench in Nova Scotia. Like the Reddins, the Creamer family was Nova Scotian of Irish Catholic descent. Physician grandfather Joseph Marie Creamer (1830-1893) emigrated to Brooklyn in 1850, where he married Ellen Tuttle, whose forebears extended back to colonial New York and included the third US vice president, Aaron Burr, and Alexander Tuttle, the first tax collector for the village of Williamsburg (now part of Brooklyn). In time, the original Dr. Creamer was appointed police surgeon for Brooklyn, and thereafter chief of autopsies for the Brooklyn Coroner’s Office. He also took up providing free medical care to the indigent, and was a benefactor of various Catholic charities.2 Three of Dr. Creamer’s sons (Joseph Jr., Alexander, and Henry) followed him into the medical profession, while a fourth (Frank) later became the Kings County (Brooklyn) sheriff.

Our subject’s father, Joseph Marie Creamer Jr., was a medical prodigy, completing his degree studies at the Medical Department of New York University before he was old enough for licensure to practice medicine in New York. Consequently, Brooklyn-born Dr. Creamer Jr. moved to Canada, initiating his professional career on Prince Edward Island, where he met and later married Catherine Reddin. The couple began their family with the birth of sons Joseph Marie III (September 1876) and Francis Alexander (January 1880) in Charlottetown. Sometime in the early 1880s, the Creamers relocated to Brooklyn, where the arrival of daughter Caroline in 1884 completed the family. There, Dr. Creamer Jr. joined his father’s medical practice, and also became active in Brooklyn Democratic Party politics. In time, he assumed the post of Brooklyn autopsy surgeon, and was thereafter elected Eastern District coroner in 1892.3 The following January, Dr. Creamer Sr. died, succumbing to cold-related pneumonia contracted after making patient house calls in inclement winter weather. Ironically, the identical fate awaited Dr. Creamer Jr. in February 1900. He was only 47, and sadly predeceased by his physician sons Alex and Henry.

The death of his grandfather, father, and brothers left our subject the only surviving doctor in the Creamer family. Raised in Brooklyn, the youngest Joseph Marie Creamer attended local schools before matriculating to St. John’s College (now University), then located in Brooklyn. At the completion of his undergraduate studies, Joe entered Long Island Medical College (now SUNY Downstate Medical Center). He was licensed in New York following his medical school graduation in 1897, and immediately joined his father’s practice.4 Two summers later, young Dr. Creamer narrowly avoided a premature death of his own, being pulled semiconscious and near-drowned from ocean surf off East Moriches, Long Island.5 The following year, he got a chance to employ his own lifesaving skills, but with unhappier results. In the crowd at the Broadway Athletic Club for the fight between heavyweight contenders Joe Choynski and Kid McCoy, Creamer was summoned to the side of spectator Byron Sabin, stricken by a heart attack, the fatal effects of which the young physician could not reverse.6 Informatively, Joe’s attendance at the Choynski-McCoy bout reflected a lifelong interest in boxing. An excellent schoolboy athlete, Creamer was a tall, burly (6 feet, 200 pounds) young man, and reportedly “settled many [playing field] disputes with his hands.”7

Although only 23 years old and a professional novice, the unexpected death of his father in February 1900 left Dr. Joseph M. Creamer III in charge of a large and thriving medical practice. Soon thereafter, he moved his office to East Side Manhattan. There, in addition to seeing his paying clientele, Joe continued the Creamer family tradition of supplying charity care to the needy. Indigent patients were treated by young Dr. Creamer at free clinics stationed at Bellevue, St. Luke’s, and Polytechnic Hospitals. During the ensuing years, Creamer combined steadily growing vocational expertise with a love of sport to expand his practice to include servicing the medical needs of Manhattan athletic clubs and other indoor sports venues. He also began attending to the health and fitness of high-profile professional boxers, particularly one-time world featherweight champion Terry McGovern.8 Later, he undertook special examination of Battling Nelson for the New York Evening World, pronouncing the lightweight champ a physical marvel with the slow heart rate and lung capacity of a world-class marathon runner.9 When professional boxing was temporarily outlawed in New York,10 Creamer turned his attention to other sports, becoming physician in attendance for bicycle races, pedestrian walking contests, and other indoor athletic events at Madison Square Garden. In keeping with another family tradition, young Dr. Creamer was a loyal Democrat, but unlike his great-grandfather (Alexander Tuttle), grandfather (Dr. Joseph M. Creamer), and father (Dr. Joseph M. Creamer Jr.), Joseph M. Creamer III neither sought nor held a politically bestowed office — at least in his early career.11

For the 1908 season, the by-now 31-year-old Creamer was retained as club physician by the New York Giants. But the circumstances of his hiring remain murky. When the details of the Giants-Cubs game umpire bribe attempt were publicly exposed the following spring, Chicago Tribune sportswriter Harvey Woodruff asserted that Creamer “was a close friend of [Giants manager John] McGraw,” and was hired as New York team physician for the1908 season without the knowledge or assent of club boss John T. Brush.12 Modern McGraw biographer Charles C. Alexander concurs, stating that Dr. Creamer was hired as Giants team physician “at McGraw’s instigation.”13 But when Brush himself inquired into Creamer’s hiring, he attributed it to club secretary Fred Knowles, not McGraw, maintaining that he (Brush) had been unaware of the physician’s retention until after the season — when Creamer presented a $2,840 bill for services rendered.14 Whatever the state of Brush’s understanding of the situation — and the usually attentive but chronically ill club boss was in poor health much of the 1908 season — Creamer’s association with the Giants was no secret to readers of Sporting Life, being regularly mentioned in the reportage of New York correspondent William F.M. Koelsch.15

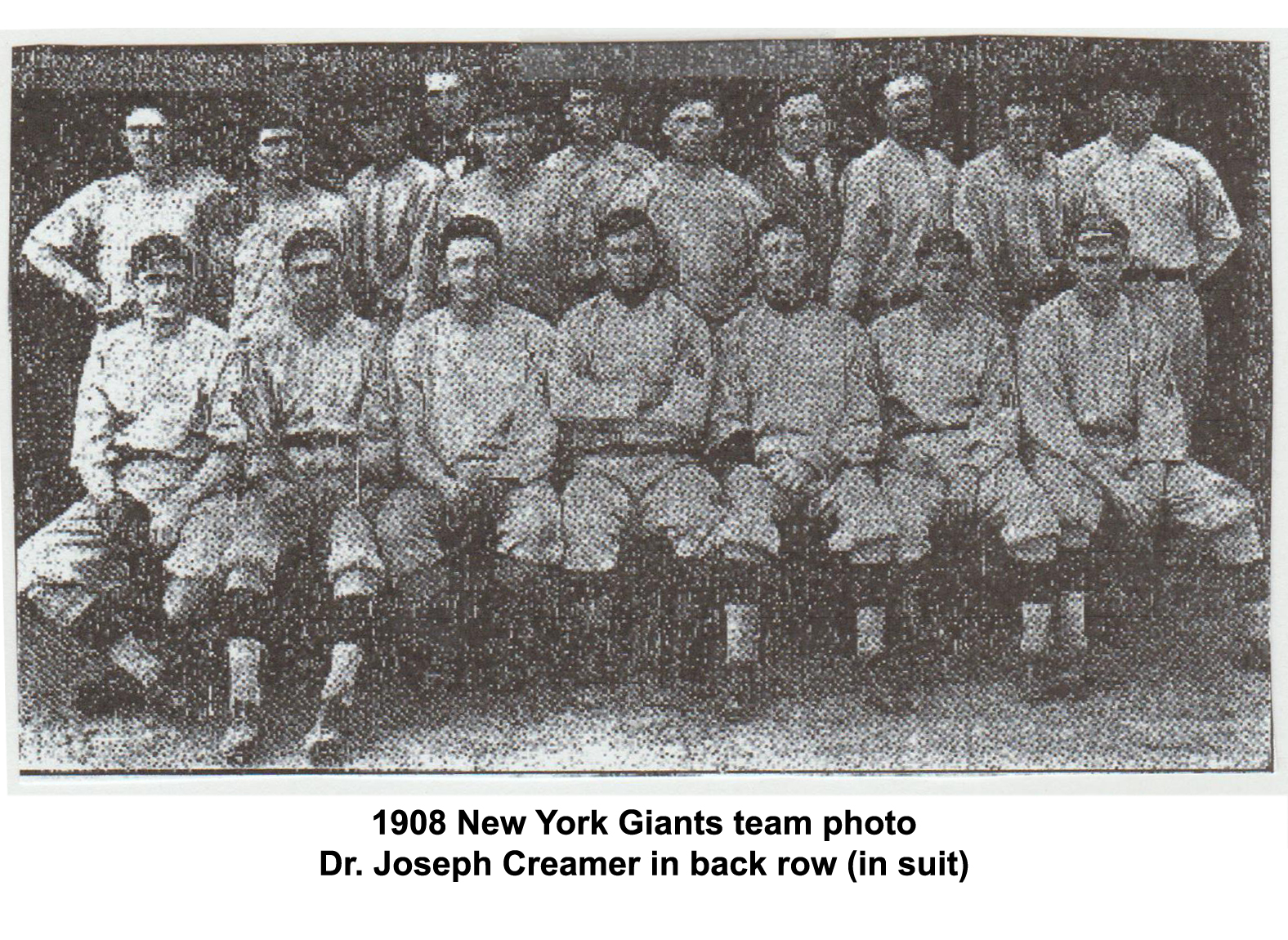

With a tight three-way (New York-Chicago-Pittsburgh) National League pennant race nearing the finish line, a variously captioned wire service article published nationwide revealed that Giants manager McGraw was counting on Dr. Creamer, the team physician, to get injured stars Roger Bresnahan and Mike Donlin back into the lineup.16 A late-season Giants team photo, meanwhile, included Dr. Creamer, standing in the back row between catcher Art Wilson and pitcher Dummy Taylor.17 In the end, the pennant was decided by the replay of a previously tied Giants-Cubs game, that contest’s highly controversial deadlock the result of cancellation of a game-winning New York run by umpire Hank O’Day, who called a force out on Giants baserunner Fred Merkle for neglecting to touch second base.

On October 8, 1908, the two clubs met at the Polo Grounds to settle the NL pennant, with the game being umpired by Bill Klem and Jimmy Johnstone. Behind some timely hitting and yeoman relief work by staff ace Three Finger Brown, Chicago prevailed, 4-2. The Cubs then went on to capture their second straight World Series crown, dusting the AL champion Detroit Tigers in five games. The defeated Giants, meanwhile, had not dispersed to their homes. Rather, they remained in New York to attend a celebrity-studded benefit held in their honor at the Manhattan Academy of Music. With the premises filled beyond capacity and the entertainment portion of the bill not yet ready to go on, master of ceremonies Joe Humphreys hauled an impromptu speaker before the crowd: Giants team physician Joe Creamer. Unprepared and visibly uncomfortable, Creamer admitted that “I’m only a stall. I’m trying to keep you quiet until things begin to happen.” He continued, awkwardly, “I’m not in the .300 batting class, so be kind enough to let me reach first base.”18 Someone in the boisterous throng then called out, “Slide for it, Joe!” whereupon “the physician slid and was declared safe.”19 Creamer was then rescued, relieved on stage by entertainer Nat Willis. Later during the festivities, John McGraw delivered a brief speech thanking attendees and promising them a Giants pennant next season. Thereafter, Mike Donlin, Roger Bresnahan, Joe McGinnity, and a dozen other Giants players were presented tokens of esteem, with Dr. Creamer receiving a gold watch fob.20

After the baseball season, Creamer resumed the duties of his regular medical practice. He also continued to serve as physician in residence for sporting events at Madison Square Garden. By this time, however, disquieting rumors about an attempt to bribe the umpires of the pennant-deciding Giants-Cubs game had begun to circulate. In-depth exposition and analysis of ensuing events is beyond the scope of this profile.21 Suffice it to say that a National League owners committee, curiously chaired by Giants boss John T. Brush, was ultimately tasked with inquiring into allegations made by umpire Bill Klem, and generally confirmed by fellow umpire Jimmy Johnstone. The two asserted that Giants team physician Joseph Creamer had offered them bribe money to call close plays New York’s way or otherwise assist the Giants to victory. The Brush committee dragged out the proceedings, with no names being revealed and little other information reaching the public until the following April. Then, Chicago Tribune sportswriter Harvey Woodruff ripped the lid off the thus-far-suppressed scandal.

In an article published on April 24, Woodruff identified the “mysterious stranger” previously under investigation and now barred from entry into any major-league ballpark as a “Dr. Creamer — without first name or initials,” as specified in the debarment notice quietly transmitted by the National Commission to all major-league club offices.22 Woodruff further identified the banished doctor as the New York Giants team physician and “a close friend of [Manager] McGraw,” but hastened to add that no charge was made that Creamer had acted on behalf of the Giants.23 In a follow-up article the next day, Woodruff quoted from an affidavit submitted to National League President Harry C. Pulliam in which umpire Klem alleged that Dr. Creamer had met Klem underneath the Polo Grounds grandstand, “holding a bunch of greenbacks in his right hand.” Creamer then said, “Here’s $2,500 which is yours if you will give all close decisions to the Giants and see that they win sure. You know who is behind me and needn’t be afraid of anything. You will have a good job the rest of your life.”24 Creamer then “mentioned the name of a well known politician who, by the way, does not know Creamer except in a casual way.”25 Klem rejected the bribe offer on the spot, and thereafter reported the incident to NL President Pulliam, who later obtained corroboration of the bribe attempt from umpire Jimmy Johnstone.26

Woodruff’s April 25 article also included Creamer’s adamant denial of the allegation. “It is a job to ruin me,” protested Creamer. “I never saw Klem or Johnstone to speak to [them] that day or any other day. I did not go outside the grandstand to meet them before the game in question, and I have never tried to bribe anybody in my life. … I cannot understand why the umpires have mixed me up in this unless it is a conspiracy of some kind.”27 The Woodruff article, however, undermined Creamer’s profession of innocence by also citing Creamer friends who “said he was being used as a tool and had been deserted by the real conspirators, said to be three members of the New York team.”28

The Woodruff expose was promptly republished elsewhere, with some accounts adding that Creamer “was a staunch Tammany man and always has been regarded as one of Big Tim Sullivan’s henchmen.”29 Then, as today, two aspects of the affair were widely accepted: (1) Creamer’s denials were not credible, as no reason existed for umpires Klem and Johnstone to invent the bribe-attempt story or to falsely identify Giants team physician Creamer as the bribe purveyor, and (2) Creamer was not acting for himself. As American League President (and National Commission member) Ban Johnson later observed, “Dr. Creamer was made the goat, a poor fellow who was, at most, acting as a messenger boy.”30 Years later, it was revealed that the “three members of the New York team” identified during Brush committee closed-door proceedings as providing the bribe money were future Hall of Famers John McGraw, Christy Mathewson, and Roger Bresnahan.31 But in late April 1909, the umpire bribery story had no staying power in the press. Even Woodruff did not pursue it. Nor were baseball fans, fixated on a new baseball season, much interested in the matter. Given that, the game’s establishment was more than content to let the contretemps die a quiet death, leaving Creamer its only casualty.32

Apart from embarrassment, the umpire bribery incident appears to have had negligible effect on the fortunes of Dr. Creamer. He retained the hospital affiliations where his free clinic work was performed, and his private medical practice continued to thrive. Creamer also remained physician in residence for Madison Square Garden sporting events. And when New York reinstated professional boxing in 1911, Creamer was appointed supervising physician by the New York State Athletic Commission. Four years later, nationwide newspaper coverage was accorded Dr. Creamer’s physical examination of heavyweight champion Jess Willard and challenger Frank Moran prior to their March 1916 title bout.33 Things also went well in Creamer’s personal life. In October 1909 he married Josephine McAleenan, the daughter of a prominent Manhattan attorney. In time, he became the father of three daughters (Anna, born 1911), Catherine (1912), and Jacqueline (1914). In addition to the Manhattan brownstone that served as the Creamer family residence, Joe acquired a summer residence in the exclusive New Jersey Shore community of Deal. About the only dark cloud on the Creamer horizon was a health concern. Barely 40, he was already afflicted with heart disease.

In May 1918 Creamer suffered a stroke. While he convalesced at his summer home in Deal, a second stroke two months later proved fatal. At the time of his death on July 28, 1918, Dr. Joseph Marie Creamer III was 41. Obituaries extolled the deceased’s charity medical care of the poor and noted his prominence as a boxing physician. No mention was made of the umpire-bribery incident of a decade earlier.34 Survivors included his wife, Josephine, and their three young daughters, his mother, Catherine Reddin Creamer, his brother, Frank, and his sister, Caroline. Following a private Requiem Mass said at St. Mary’s of the Assumption Church in Deal, Creamer was interred in the McAleenan family vault at Calvary Cemetery, Woodside, Queens. Buried with Dr. Creamer was something else: a definitive answer to the question of who was behind the attempt to bribe the umpires of the pennant-deciding Giants-Cubs game of 1908.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin. It was originally published in the SABR Deadball Era Committee newsletter, The Inside Game, Vol. XIX, No. 2 (Spring 2019).

Sources

The primary sources of the biographical information provided herein were contemporaneous newspaper articles and Creamer family posts accessed via Ancestry.com. Information on the 1908 umpire-bribery attempt and ensuing investigation was taken from contemporary reportage and the commentary and analysis of Angelo J. Louisa and Floyd Sullivan in “The Strange Death of Harry C. Pulliam,” Mysteries from Baseball’s Past: Investigation of Nine Unsettled Questions, Louisa and David Cicotello, eds. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010); Cait Murphy, Crazy ’08: How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History (New York: Smithsonian Books, 2007), and David W. Anderson, More Than Merkle: A History of the Best and Most Exciting Baseball Season in Human History (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000).

Notes

1 Various sources, including certain of Creamer’s July 1918 obituaries, state that Joseph Marie Creamer III was born in Brooklyn in 1870. These data are incorrect, refuted, among other things, by the fact that Creamer’s parents were not married until July 1875 (in St. Dunstan’s Cathedral in Charlottetown); the birth of younger brother Frank in Charlottetown in January 1880; Dr. Creamer Jr.’s maintenance of his medical practice in Charlottetown until the early 1880s, and by the designation of Joseph M. Creamer III as a naturalized (as opposed to native-born) citizen on the 1910 US Census.

2 As per the obituaries published for Dr. Joseph Creamer in the New York Evening Telegraph, January 8, 1893, and Ellen Tuttle Creamer in the Brooklyn Eagle, May 4, 1905.

3 As per “Dr. Joseph Creamer Dead,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 23, 1900.

4 Biographical information derived from obituaries published for Dr. Joseph M. Creamer III in New York and New Jersey daily newspapers in late July 1918.

5 See “Saved Sheriff Creamer’s Nephew,” New York Times, July 30, 1899.

6 See “Drops Dead at Prize Fight,” Chicago Tribune, January 13, 1900.

7 As noted in “Doc Creamer Dies,” New York Sun, July 29, 1918.

8 As reported in the Oshkosh (Wisconsin) Daily Northwestern, May 27, 1903, and Oakland Tribune, April 7, 1907.

9 See Bozeman Bulger, “N.Y. Doctor Tells Why Nelson Is Physical Marvel,” New York Evening World, November 6, 1903.

10 The Lewis Law prohibition of professional boxing matches did not extend to the amateur and club member bouts held at the NYC athletic clubs serviced by young Dr. Creamer.

11 That would change a decade later, Dr. Creamer’s 1911 appointment as supervising physician of the New York State Athletic Commission being a political sinecure.

12 See Harvey Woodruff, “ ‘Dr. Creamer’ Barred from All Major League Ballparks,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1909.

13 Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw (New York: Viking Press, 1988), 137.

14 See William F.M. Koelsch, “New York Notes,” Sporting Life, November 14, 1908. See also, Angelo J. Louisa and Floyd Sullivan, “The Strange Death of Harry C. Pulliam” in Mysteries from Baseball’s Past: Nine Unsettled Questions, Louisa and David Cicotello, eds. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010), 53.

15 See e.g., “New York Notes,” Sporting Life, June 13, August 22, and September 19, 1908. See also, J.C. Morse, “Boston Briefs,” Sporting Life, September 12, 1908.

16 See e.g., “Crippled Giants Have Hard Row to Hoe,” Sacramento Bee; “Giants Manager Says Team Is Injured,” Charleston (South Carolina) Evening Post, and “M’Graw in Hard Luck,” Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, all published September 30, 1908.

17 See e.g., New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 28, 1908.

18 As reported in “Baseball Throng Welcomes Giants,” New York Times, October 19, 1908. Interestingly in light of future events, the gala’s souvenir program contained photos of prominent Tammany Hall figures/Giants supporters, including Big Tim Sullivan and his cousin, Little Tim Sullivan.

19 Ibid.

20 See “Series with Tigers Planned for Giants,” Washington (DC) Evening Star, October 19, 1908. The players also received shares of a $3,700 fund collected from attendees and other gala subscribers.

21 Those seeking detailed commentary and analysis of the affair should consult Louisa and Sullivan, cited in endnote 14, above.

22 Woodruff, Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1909.

23 Ibid.

24 Harvey Woodruff, “East Hears of ‘Dr. Creamer,’” Chicago Tribune, April 25, 1909.

25 Ibid. Although the context is garbled, it appears here that Woodruff injected his own purported knowledge of the NYC political scene, rather than Klem’s.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 See e.g., “ ‘Dr. Creamer,’ Who Doctored Giants, Barred from Parks,” (Springfield) Illinois State Journal, April 25, 1909. That East Side Manhattan resident Creamer and Big Tim (Timothy Daniel) Sullivan, a New York state senator from East Side Manhattan and Tammany power broker, would have been acquainted is more than likely. Creamer was also a neighbor and sometime physician to Little Tim (Timothy Paul) Sullivan, Big Tim’s cousin and another influential Tammany Hall insider. When Little Tim died in late December 1909, Dr. Creamer informed the press of the cause of death (Bright’s disease and endocarditis). See “Little Tim Sullivan Dead at Forty,” New York Times, December 23, 1909. But evidence that Creamer served as a Sullivan “henchman” is nonexistent, unless one accepts the much embellished account of the bribery incident provided by Bill Klem in a 1951 magazine article. See W.J. Klem and W.J. Slocum, “Umpire Bill Klem’s Own Story,” Collier’s, March and April 1951. The writer does not.

30 See W.A. Phelon, “Chicago Chat,” Sporting Life, December 18, 1909.

31 See Louisa and Sullivan, 57-58, and Cait Murphy, Crazy ’08: How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History (New York: Smithsonian Books, 2007), 285, citing the minutes of the National League winter meeting in February 1909.

32 Again, for more thorough detail and analysis of the affair than provided herein, see Louisa and Sullivan, 50-60.

33 Se e.g., “Doctor Declares Both Boxers Fit to Fight,” Boston Herald; “Physician Examines Willard and Moran,” Charlotte Observer; “Doc Gives Jess and Frank a Once Over,” Colorado Springs Gazette, all published March 21, 1916. Willard retained the crown via a 10-round decision.

34 See e.g., the Creamer obituaries published in the Trenton Evening Times, July 29, 1918, and New York Tribune and New York Times, July 30, 1918.

Full Name

Joseph Marie Creamer

Born

September 21, 1876 at Charlottetown, PEI (CA)

Died

July 28, 1918 at Deal, NJ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.