Showdown: Babe Ruth’s Rebellious 1921 Barnstorming Tour

This article was written by T.S. Flynn

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

A day after the New York Yankees lost the 1921 World Series to their landlords, the New York Giants, the squad gathered at the Polo Grounds to divide $87,756.67, the losers’ share of the postseason proceeds. During the meeting, each player also received a letter signed by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis reiterating Article IV, Section 8(b) of the rules governing Organized Baseball: “Both teams that contest in the world’s series are required to disband immediately after its close and the members thereof are forbidden to participate as individuals or as a team in exhibition games during the year in which the world’s championship was decided.”1

A day after the New York Yankees lost the 1921 World Series to their landlords, the New York Giants, the squad gathered at the Polo Grounds to divide $87,756.67, the losers’ share of the postseason proceeds. During the meeting, each player also received a letter signed by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis reiterating Article IV, Section 8(b) of the rules governing Organized Baseball: “Both teams that contest in the world’s series are required to disband immediately after its close and the members thereof are forbidden to participate as individuals or as a team in exhibition games during the year in which the world’s championship was decided.”1

On that same morning, an item had appeared in the Bridgewater (New Jersey) Courier-News: “Carl Mays’ All Stars — with ‘Babe’ Ruth and probably [Bob] Shawkey, [Bill] Piercy, [Wally] Schang and other Yankees — are booked to play the Meadowbrooks in Newark tomorrow afternoon.”2 Ruth was under contract to play in 17 additional exhibitions during the fall and early winter of 1921, headlining a tour originating in New York and Pennsylvania before moving westward to locales including Oklahoma, Missouri, Texas, and Utah.

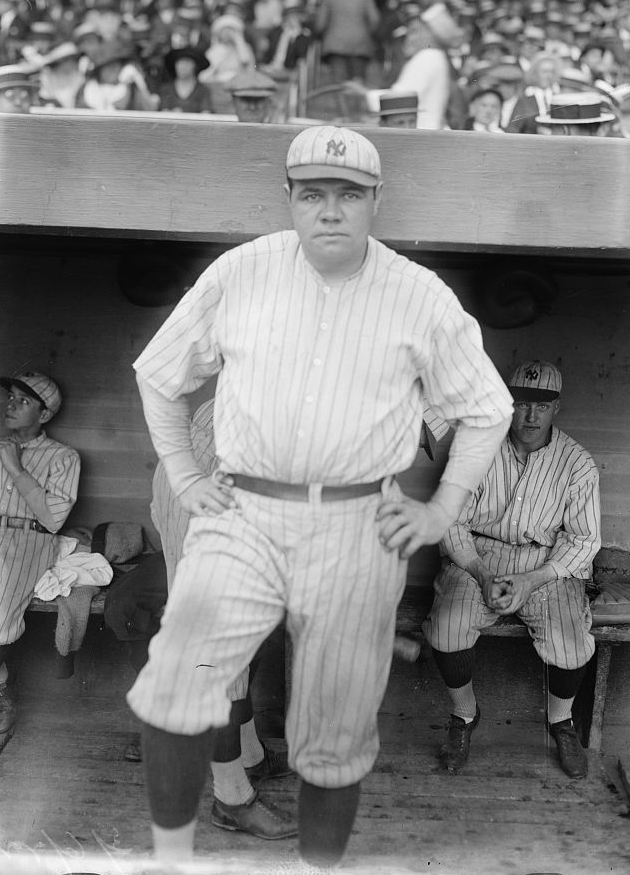

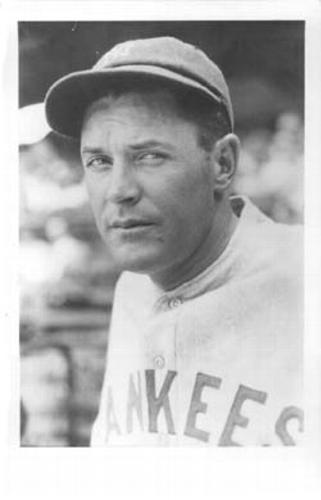

The World Series had been a disappointing conclusion to The Babe’s spectacular regular season, his second with the Yanks. He broke Roger Connor’s career record of 138 home runs on July 18 — a record since 1897 — when he blasted a 560-foot shot at Detroit, his 36th round-tripper of 1921.3 He finished the season leading all of baseball with 59 home runs (breaking his own record of 54, set in 1920), 12.9 WAR, 1.359 OPS, 177 runs, and 457 total bases (79 more than runner-up Rogers Hornsby).

Ruth had revolutionized baseball, altering the game with his prodigious power and personality, and it was widely believed that he’d end his spectacular season by carrying his club to its first World Series championship. But the Yankees lost the best-of-nine series to the Giants in eight games. An infected boil on Ruth’s elbow limited his participation to the first five games and one desperate pinch-hitting appearance in the bottom of the ninth inning of the final game. He grounded out to first. Two outs later, both the Series and Ruth’s two-year, $40,000 contract with the Yankees ended. He intended to negotiate a new contract during the offseason, but first he planned to make some dough plying his trade in small towns across America.

The Newark exhibition was canceled when Schang and Mays bowed out, unwilling to test Landis’s resolve. Ruth, unswayed, phoned the commissioner to discuss his offseason plans. “He’s an obstinate man,” the Babe said when asked about the call. “He hung up on me twice.”4 Ruth insisted he’d play as planned the following day, October 16, in Buffalo. He and teammates Bill Piercy and Bob Meusel, along with former teammate and roommate Tom Sheehan, were scheduled to compete against a squad calling themselves the Polish Nationals. As was customary on tours such as this, local semipros would fill out the rogue Yankees’ roster.

Fundamentally, Ruth considered the barnstorming ban unfair. Players on third- and fourth-place teams were allowed to tour despite receiving World Series shares, he argued, and although the rule had been on the books for years, its enforcement was uneven. When Ruth and other Red Sox barnstormed after the 1916 World Series, their punishment had been individual fines of $100. When World Series participants barnstormed in 1919 and 1920, the leagues took no action.5

But Landis was uninterested in debating the rule’s history or fairness in 1921. “The rule was drawn up some time ago and applies only to teams which take part in a world’s series. It is a rule and as such must be enforced,” the commissioner insisted.6 “If the Babe defies the order, it will be a personal issue between Ruth and me to determine which man is the bigger in baseball.”7

Riding a wave of popularity and emboldened by the support of most big-league owners following his lifetime banishment of the 1919 Black Sox, Landis saw Ruth’s rising popularity as a threat to the balance of power in the game. Kansas City sportswriter Alport Hager claimed, “No living American — or dead either, for that matter — has received more publicity than Babe Ruth, unless it be our presidents and possibly ‘Billy’ Sunday. There is not a ‘burg’ in the country from coast to coast, a mining town in Alaska or a hamlet in Canada, where his name is unknown. The Cuban school boys, where the game is popular, know more about Ruth than they do of Cuba Libre.”8

Less well known was the origin of the barnstorming ban and the central role Cuba played in its establishment. In December of 1910 the Detroit Tigers and the World Series champion Philadelphia Athletics (with notable exceptions manager Connie Mack, second baseman Eddie Collins, and third baseman Home Run Baker) toured Cuba and played exhibition games against Havana and the defending island champions, Almendares.

Upon learning of the trip, American League President Ban Johnson said, “I was not in favor of the Athletics tour to Cuba, but the news did not reach me in time to ask them not to go through with it. You see, for the world’s series games we ask raised prices from the fans, because this is the most important of all games. Then for the champions to put themselves on display in exhibition clashes does not quite appeal to me. The Athletics, by defeating the Cubs, are supreme in baseball, but, being off their stride now as a result of the long layoff, these Cubans probably will beat and outplay them. The Athletics can gain nothing by winning and it would certainly injure their standing to be beaten.”9 And beaten they were. The A’s lost the first game on the tour to Detroit, 6-2, before playing each Cuban team five times. The Mackless Men won just four of those games, going 2-3 against each Cuban squad.10

While Johnson, and later Landis, publicly expressed concern for the integrity of the World Series as the reason behind the barnstorming ban, the public and press were unconvinced. News reports from the 1910 Athletics tour made clear that the depleted roster affected the outcome of the games, and fans didn’t confuse the results of exhibitions with sanctioned championship contests.

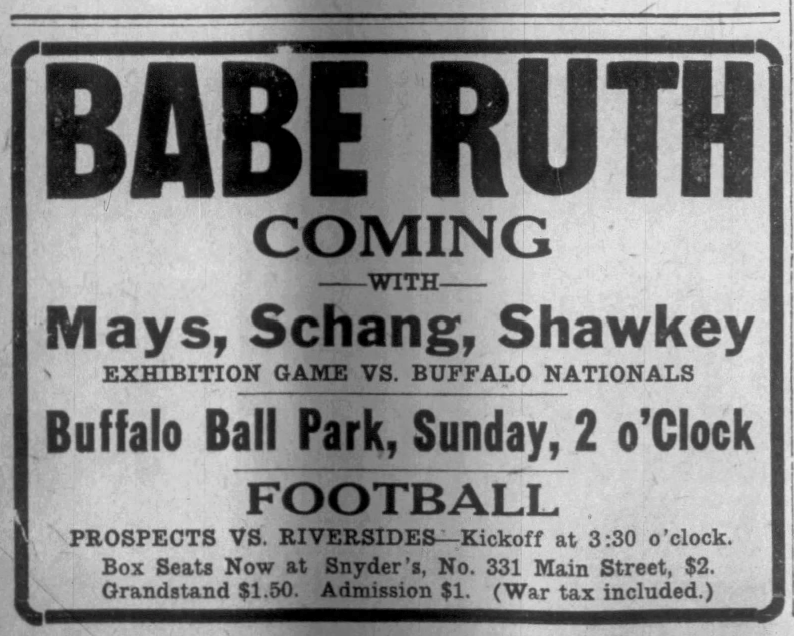

“Babe Ruth Coming” advertisement that appeared in the Buffalo Courier, October 15, 1921.

During the escalation of The Babe’s barnstorming brouhaha of 1921, John B. Foster, writing for the Washington Evening Star, suggested another reason for the prohibition: “The rule against barnstorming by world series contestants was passed because certain players in the past met objectionable characters and engaged with them on the diamond to the detriment of base ball. The players have not always been careful what they have done. They have gone into games with ineligible players, with players of outlaw leagues and with negro teams, which doesn’t find favor with the owners.”11 In fact, the 1910 Havana club that took three of five from the A’s was “an exclusively negro team … native Cuban with the exception of three or four American negroes, secured from the crack Leland Giants, of Chicago [Grant Johnson, Pop Lloyd, Pete Hill, and Bruce Petway].”12 Likewise, Almendares was “practically an exclusively native team, but two or three of its men [were] white Cubans.”13

Organized Baseball’s opposition to barnstorming became codified in the American League in 1910, shortly after the Athletics and Tigers returned from their tour. In 1916 the rule was expanded to cover both leagues. Players who toured during the offseason often earned more income from barnstorming than from their regular-season salaries, thereby calling into question the market value for their services. By 1921 Organized Baseball had already weathered three attempts by players to unionize (1885, 1900, and 1912),14 and conditions were ripe for another effort. “[Babe Ruth’s 1921 outlaw tour] lends credence to the fact that a new baseball players’ organization is in the making, and that Ruth, Meusel, and the others have been selected as the rebels to make the fight for the men against the existing powers in the game.”15

Organized Baseball’s opposition to barnstorming became codified in the American League in 1910, shortly after the Athletics and Tigers returned from their tour. In 1916 the rule was expanded to cover both leagues. Players who toured during the offseason often earned more income from barnstorming than from their regular-season salaries, thereby calling into question the market value for their services. By 1921 Organized Baseball had already weathered three attempts by players to unionize (1885, 1900, and 1912),14 and conditions were ripe for another effort. “[Babe Ruth’s 1921 outlaw tour] lends credence to the fact that a new baseball players’ organization is in the making, and that Ruth, Meusel, and the others have been selected as the rebels to make the fight for the men against the existing powers in the game.”15

His demands ignored, Landis confronted the perceived threat with the full power of his office, contacting Organized Baseball operators across the country and warning them not to open their ballparks to Ruth or any other ineligible players during the offseason. Any team failing to comply would face a season-long suspension.

Local promoters and Ruth’s tour managers, Connie Savage and Charles W. Lynch, scrambled to find a suitable replacement venue in Buffalo. With just hours to spare, the game was moved to Legionnaire Park, a venue ill-equipped for a large crowd. Many fans stayed home, but the teams still played. “Piercy pitched, Meusel played at shortstop, Sheehan covered right field and Babe decorated first base,” his elbow still heavily bandaged.16 Ruth and Meusel hit back-to-back home runs in the sixth inning, and the barnstormers won the contest, 4-3.17

Landis spent the day traveling from New York to his office in Chicago. After the game, Ruth told local newspapermen, “I am doing this with full knowledge of what it may mean and am not worrying about the consequences. I believe I am right, and that it is time a move of this kind was made for the ball players. The interests of organized base ball are served when a man gives them full effort and carries out every phase of his contract for the season’s period. When the bell rings after the world series why should I or any other player be kept from earning money?”18

The money at issue was significant. Ruth and the other barnstorming Yankees were promised a big payday for the Buffalo game, “but when the scene shifted to a sandlot field, Babe’s $4500 guarantee faded. Babe probably didn’t have much more than carfare when the day’s work was over.”19

“Back in Chicago, [Landis] said he had a number of questions to attend to before the matter of the great swatter’s defiance of his order concerning exhibition games.”20 Ruth and his teammates continued the tour, beginning with games in the New York towns of Elmira (October 17) and Jamestown (October 18). Yankees owners Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast Huston issued a statement to the press: “It is regrettable that the rule … has been violated so defiantly by some of the Yankee players. Judge Landis has no alternative but to meet the situation firmly.”21 The commissioner’s hard line had escalated the situation and created a dilemma. Suspending Ruth for the 1922 season — or even for a significant portion of it — would deal a serious financial loss to Ruppert and Huston, two of the commissioner’s “staunchest supporters.”22

“Fate of Swatting Babe” headline appeared in the Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 18, 1921.

Ruth responded to the escalating public-relations battle with his most effective weapons: his popularity and baseball skills. He dazzled fans in Elmira with a pair of home runs and exhibited charitable largesse when he insisted that hundreds of “small boys hanging wistfully around the outside of the park [be] let in” free of charge.23 After leading his club to a 6-0 victory, The Sultan of Swat addressed the barnstorming hullabaloo: “I know I am right and Landis is wrong and that we will fight it out. I think the trouble with Landis is that he is getting a little too big headed over his job.”24 When asked what he’d do in the event of a long suspension, Ruth laid out his plan: “I will continue to play baseball next year, that’s a cinch. If I organize my own team, however, it won’t be a team of outlaws. By that I mean players who have been thrown out of the game for gambling and things like that. I won’t have anything to do with those former Chicago White Sox players who were mixed up in that world series scandal. But my team would be formed of good, clean fellows, players who are straight, but who have jumped from the American League.”25

The next day, the barnstormers played through persistent rain in Jamestown, winning 14-10. “The game was played on the Coloron grounds on the shore of Chataqua [sic] Lake, and for the first time in history the ball was knocked into the lake, Ruth doing the trick during an exhibition of batting which preceded the game. During the game Ruth got a couple of two-baggers, but failed to get a home run.”26 Before departing for Warren, Pennsylvania, where the barnstormers were scheduled to play the following afternoon, Ruth reasserted that he was right in his fight with Organized Baseball. “He cited the case of George Sisler, of the St. Louis Browns, who is now said to be playing ball in the west. ‘Sisler shared in third club money … but he is not molested by Judge Landis. Meusel, Piercy, and Sheehan are going to stick with me and we are going right along with our schedule until early in November, when I begin a vaudeville engagement at Mount Vernon, N.Y.’”27

On the fourth day of the tour, Babe Ruth’s All-Stars defeated the Warren Independents, 5-3, in front of 2,000 fans. Ruth hit a home run and even pitched an inning but, heeding the advice of Christy Walsh, “the manager of a syndicate handling his writings,” he refused to discuss the Landis matter after the game.28

Hornell, New York, hosted the fifth exhibition of the tour, on October 20. After breakfast in the small town, Ruth hired a car to drive him to St. Ann’s Cemetery to visit the grave of Tommy Padgett, with whom he had roomed and played ball at St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, in Baltimore. Padgett signed with the Class-D Hornell Green Sox in 1914 shortly before Ruth signed to play for the Double-A Baltimore Orioles. Padgett’s baseball career lasted two seasons. He enlisted in the Army at the outbreak of the Great War and was wounded while serving overseas. Upon recovery, he returned to Hornell and found work as a railroad brakeman. During his third day on the job Padgett fell between two freight-train cars “and was cut to pieces.” Ruth spent 30 minutes at his fallen pal’s gravesite.

Besides promising the proceeds of the day’s game (above the guarantee), The Bambino pledged 20 percent of his personal share to the local children’s home.29 The weather didn’t cooperate. “Hours of rain converted the diamond into a sea of mud in which the big Bambino floundered and slipped and fell. Only three innings were played, and Ruth was permitted to bat half a dozen times. He didn’t knock a single pitch out of the infield, but Bob Meusel cracked one over the race track fence, breaking a record that had stood for ten years.”30 To assuage the large crowd that had rousingly welcomed the ballplayers to Hornell, Ruth spoke at a local theater that evening, giving “a brief talk on baseball in general.”31 He said the Yankees would have won the World Series if his arm had been healthy, but he declined to comment on the showdown with Landis, other than to announce that the barnstorming tour would end in two weeks.32

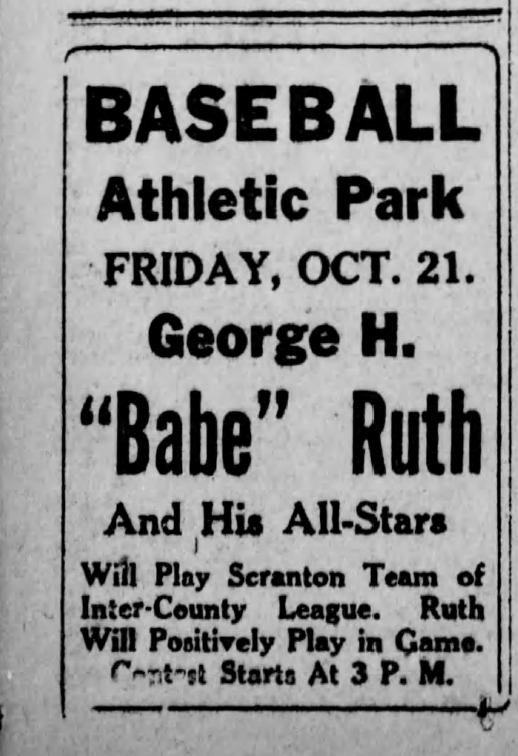

After spending the night in Hornell, the rogue Yanks planned to cross back into Pennsylvania, where they were scheduled to play a team of semipros from the Inter-County League at Scranton’s Athletic Park on Friday, October 21. As with the first five games of the tour, the price of admission would be $1. Rumors had appeared in newspapers around the country that Landis would impose a long suspension for Ruth, perhaps as lengthy as a full season. Promoters, in turn, proposed a yearlong barnstorming tour or a third major league for Babe to call home,33 promising the star as much as $1,000 per day.34

The financial outlook for the current tour was less promising. The Burlington (Vermont) Daily News reported, “From pretty good authority, we learn that Babe Ruth’s Stars have not been packing ’em along the line thus far. The attendance for the first three days was reported to have been about 1,500 a game at $1 a head. The actual paid attendance at one of the games was 1,102 persons. … Unless the Babe can draw an average attendance of at least 2,000 at $1 each, it is impossible to see where the Ruth tour will weather things financially. He will be barred from the real parks in cities represented in organized baseball, and the kerosene oil circuit will not come across a dollar a smash.”35

“Baseball Athletic Park” advertisement appeared in the Scranton Republican, October 17, 1921.

After his theater appearance in Hornell, The Babe spoke by phone with Huston. The Yankees co-owner “pointed out to Ruth the consequences of his actions and told him that the New York American League Club, by losing Ruth’s services during part of next season, would be the real sufferer in the controversy.”36 Ruth did not want to hurt the club or his teammates, and he indicated a willingness to cancel the tour after the next day’s game in Scranton. The hassles associated with the unavailability of minor-league ballparks and the increasingly bad weather probably influenced the decision. It was a good time to cut the tour’s compounding losses and prepare for his vaudeville engagement.

Huston, delighted by Ruth’s acquiescence, arrived in Scranton by train the next morning and checked into the Hotel Casey at about 9 o’clock. “Ruth, at the head of a delegation of one dozen men — players on his outlaw team and men he carried along in building up his outlaw organization — reached Scranton at 10:15. They immediately went to the Hotel Casey, where a short time after registering Ruth left the party and went to the room occupied by Colonel Huston. … The conference [to arrange for the cancellation of the tour] lasted close to one hour, after which Ruth dressed for the ball game at Athletic Park, and Colonel Huston prepared for his return to New York.”37 The barnstormers lost on the field that afternoon, falling to Scranton’s Inter-County team, 8-6, their first defeat of the tour. Ruth and Meusel spent the evening with their Yankees teammates Mike McNally and Wally Schang, Cleveland Indians catcher Steve O’Neill, and featherweight boxing champion Johnny Kilbane. The athletes “made merry at a quiet dinner held in honor of the home run king.”38

On the morning of October 22, Ruth met with the sporting editor of the Scranton Republican to officially announce the cancellation of the tour. He declined to address the details of the confab with Huston, saying only that the tour had ended and that the other barnstorming players supported the decision. “Asked whether he ‘surrendered to organized baseball, the home run king answered that he wouldn’t exactly call it ‘surrendering.’”39 At 3:47 P.M., Ruth departed Scranton on a train bound for his home in New York City.40

In a syndicated newspaper column published on October 24, Ruth wrote, “The best argument I heard at Scranton the other day as to why I should abandon barnstorming was that ‘Wise men change their minds, fools never.’ I never expect to be in Solomon’s class, but I am glad that Col. Huston prevented me from getting in the other classification. … The reason I started barnstorming was to do something, according to my way of thinking, that would help baseball players as a whole. The reason I stopped was to show my appreciation of Col. Ruppert and Col. Huston, who brought me to New York at an enormous expense and who have treated me fair and square ever since.” Ruth added that he had “nothing but the highest regard and respect for [Landis] and the difficult position he holds.”41

Landis remained silent on the matter for more than a month. Finally, on December 5, he suspended Ruth and Meusel from Opening Day to May 20. Besides forfeiting six weeks of the season, the two Yankees were ordered to return their World Series shares. Since Sheehan and Piercy hadn’t been on the Yankees’ World Series roster, they received no punishment for participating in the tour.42 On December 20 Piercy was traded to the Red Sox with Rip Collins, Roger Peckinpaugh, Jack Quinn, and $100,000 for Bullet Joe Bush, Sad Sam Jones, and Everett Scott. Sheehan pitched in St. Paul in 1922, earning 26 of the Saints’ 107 regular-season wins.

Fans petitioned Landis throughout the winter, begging him to rescind or shorten the suspensions for Ruth and Meusel, but Landis remained obstinately silent on the matter throughout the winter. Ruth quit the vaudeville tour early, in February, and traveled to Hot Springs, Arkansas, to relax for two weeks before joining the Yankees spring-training camp in New Orleans.43 Huston met The Bambino in Hot Springs and they quickly came to agreement on Babe’s new $52,000 annual contract. In late March Landis arranged to meet with Ruth in New Orleans. After emerging from their hourlong meeting, Landis told the press he’d make a statement after the Yankees’ exhibition game that afternoon. With expectations raised, a flock of newsmen gathered for the announcement. John Kieran reported, “The Judge cleared his throat, gave a tug to the front of his coat amid a silence like that which reigns in the depths of northern forests, he snapped out: ‘I have nothing whatever to add to my former statement.’”44

Attempting to offset the financial impact of the Babe’s suspension, the Yankees embarked on a preseason exhibition tour of Texas, attracting “huge crowds from Galveston to San Antonio to Dallas.”45 Landis had won the barnstorming battle with Ruth, but American League attendance figures for April and May of 1922 proved that Ruth was the bigger man in baseball. Fans bought fewer than half the tickets to Yankees games at home and on the road than they had in 1921.46 Landis continued to rule the game with a heavy hand and an appetite for photo opportunities. Before officially ending their suspensions, the commissioner required formal applications for reinstatement from Ruth and Meusel. Finally, on May 20, 1922, the two chastened Yanks returned to the game and were welcomed by 40,000 fans at the Polo Grounds. Legendary sportswriter Heywood Broun compared Ruth’s return to that of the Prodigal Son. He was gifted not with a fatted calf but a silver bat, silver cup, and a floral wreath in the shape of a baseball diamond.47

T.S. FLYNN is an educator and writer in Minneapolis. His articles on Oil Can Boyd, J.R. Richard, the 1921 World Series, and the 1925 World Series have appeared in SABR books. He has written short fiction, essays, articles, and reviews for a variety of publications, including Hobart, The Classical, and the Peoria Journal Star.

Sources

In addition to the sources identified in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Giants and Yankees Warned Against Barnstorming Trips,” New York Tribune, October 15, 1921: 14.

2 “Mays and Ruth in Newark,” Bridgewater (New Jersey) Courier-News, October 14, 1921: 12.

3 Mike Huber, “July 18, 1921: Babe Ruth’s 560-Foot Blast Against Tigers Sets Career Home Run Record,” sabr.org/gamesproj/game/july-18-1921-babe-ruth-s-560-foot-blast-against-tigers-sets-career-home-run-record

4 “Babe Ruth and Pals Defy Landis, Play Proscribed Buffalo Game,” Buffalo Morning Express, October 17, 1921: 1.

5 Edmund F. Wehrle, Breaking Babe Ruth: Baseball’s Campaign Against Its Biggest Star (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2018), 75.

6 “Babe Ruth to Play at Buffalo Despite Judge Landis’ Edict,” Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), October 16, 1921: 15.

7 “Baseball Row in Its Climax Hits Buffalo,” Buffalo Morning Express, October 16, 1921: 59.

8 Alport Hager, “Playing the Game,” Kansan (Kansas City, Kansas), October 16, 1921: 27.

9 “No Barnstorming to Be Permitted,” Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), December 1, 1910: 8.

10 “Baseball Gets Big Boom in Cuba,” Central New Jersey Home News (New Brunswick), December 21, 1910: 7.

11 John B. Foster, “Public Sympathy is with Athlete,” Washington Evening Star, October 18, 1921: 24.

12 Cesar Brioso, personal interview, citing Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 by Jorge S. Figueredo (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003).

13 Joe S. Jackson, “Boston Nationals on List of Spring Visitors Here,” Washington Post, December 8, 1910: 8.

14 “History of the Major League Baseball Players Association,” mlbpa.org/history, 2014.

15 “Ruth’s Rebellion Is Seen as Big New War,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 18, 1921: 16.

16 “Ruth Is Fighting Organized Baseball, Not Judge Landis,” Buffalo Commercial, October 17, 1921: 6.

17 Ibid.

18 “Flouts Ban of Judge on Playing Exhibitions,” Washington Evening Star, October 17, 1921: 26.

19 “Ruth Is Fighting Organized Baseball, Not Judge Landis.”

20 “Ruth’s Rebellion Is Seen as Big New War.”

21 “Landis to Let ‘Gravitation’ Attend to Ruth,” Chicago Tribune, October 18, 1921: 17.

22 Damon Runyon, “Fate of Swatting Babe Hangs on Word of Itinerant Judge,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), October 18, 1921: 16.

23 “Ruth Plays at Elmira,” Pittsburgh Post Gazette, October 18, 1921: 11.

24 Ibid.

25 “Ruth Threatens to Organize His Own Baseball Team,” Mt. Vernon Register News (Illinois), October 18, 1921: 1.

26 “I Don’t Care, Says Ruth, Just Like Eva Tanguay,” Baltimore Sun, October 19, 1921: 11.

27 Ibid.

28 “Ruth’s Stars Defeat Warren,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, October 20, 1921: 10.

29 “Big Bambino Places Wreath on Mound of Boyhood Pal,” Buffalo Enquirer, October 20, 1921: 6.

30 “Ruth Blames Sore Arm for Yank’s Defeat,” Buffalo Commercial, October 21, 1921: 6.

31 “Rain Prevents Ruth Contest,” Elmira Star-Gazette, October 21, 1921: 19.

32 “Ruth Blames Sore Arm for Yank’s Defeat.”

33 “Third Big League in Making Says Report Movie Men Are Behind Project,” Oregon Daily Journal (Portland), October 22, 1921: 8.

34 “Bait Babe Ruth With Huge Sum of $250,000.” Burlington (Vermont) Daily News, October 22, 1921: 8.

35 Ibid.

36 Babe Ruth Repents; Quits Exhibitions,” New York Times, October 22, 1921: 16.

37 “‘Babe’ Ruth Ends Baseball Revolt,” Scranton Republican, October 22, 1921: 15.

38 Ibid.

39 “Babe Ruth Ends His Revolt Breaking Up Barnstorming Troupe,” Scranton Republican, October 22, 1921: 1.

40 Ibid.

41 Babe Ruth “Wanted to Help Players,” Pittsburgh Press, October 24, 1921: 19.

42 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 145.

43 Montville, 146.

44 Wehrle, 82.

45 Ibid.

46 Wehrle, 83.

47 Wehrle, 83-84.