Boston Brotherhood/Reds team ownership history

This article was written by Charlie Bevis

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

An ownership history for Boston’s Players League franchise (1890) and American Association franchise (1891).

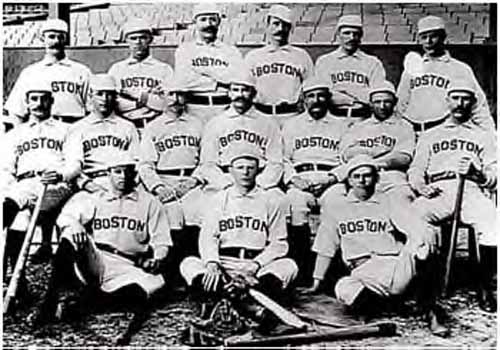

Competing against the firmly entrenched Boston ballclub in the National League, the Boston Brotherhood/Reds club won consecutive championships, in the Players’ League in 1890 and in the American Association in 1891. The club disbanded when it was bought out in the NL-AA merger, which was consummated in December of 1891.

Under the corporate name of the Boston Ball Club, the Brotherhood/Reds club was a stock company organized on November 29, 1889, to compete in the newly established Players’ League for the 1890 season. The club raised $20,000 in capital, through the sale of 200 shares of stock priced at $100 each, and received a corporate charter from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts on December 14, 1889.1 A diversified group of 26 stockholders initially financed the club, with the largest individual holding a 15 percent ownership interest.2

During the 1890 season, the Boston Ball Club was known in Boston as the Brotherhood club, based on the league’s organizer, the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players, which mandated that players constitute at least half of a club’s board of directors.

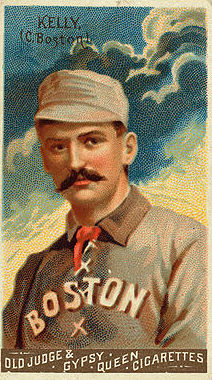

At the first corporate meeting, the stockholders elected Charles H. Porter as president, Frederick E. Long as treasurer, and Julian B. Hart as secretary; on the board of directors were four stockholders (Porter, Hart, Charles A. Prince, and an unidentified fourth man) and four ballplayers (Dan Brouthers and Mike Kelly, initially; later joined by Arthur Irwin and Hardie Richardson).3

Porter, the titular head of the organization, gave the new ballclub credibility since in 1873 he had been president of the Boston club in the National League.4 Long had been the treasurer of Boston NL club from its formative years through 1880. Hart, a local businessman, was the day-to-day executive and public face of the club. Prince was general counsel of the New York & New England Railroad.

Unlike the financing of other clubs in the Players’ League, the investors in the Boston Ball Club were baseball fans first, not primarily capitalists looking to turn a quick profit. Among the officers and directors, Hart held the largest stake with 28 shares, followed by Long with 10, Prince with 5, and Porter with 2.5 The other 22 stockholders included super-fan Arthur Dixwell (35 shares, the largest stake in the club); businessmen Frank Foss (10) and John Haynes (9); sporting-goods merchants George Wright (5) and John Morrill (5); and ballplayers Irwin (12), Brouthers (10), Richardson (10), Kelly (5), and Bill Nash (5).6

Most of the nonplayer investors in the Boston Brotherhood club had been regular spectators during the 1889 season of the Boston NL club. Several were also disgruntled former minority stockholders of the Boston NL club, which made them highly motivated to achieve success with the Brotherhood club. The minority stockholders had filed a lawsuit in 1888 seeking to force the controlling-interest triumvirate of stockholders to provide an accounting of the club’s finances, but they lost in court and had to sell their shares at below-fair-value prices to the majority group.7

Many of the ballplayers signed by the Boston Brotherhood club jumped their contracts with the Boston NL team, led by the highly popular Kelly. This exodus created a superior product to attract baseball fans to the Brotherhood games played at the Congress Street Grounds, in comparison to the diluted product fielded by the Boston NL team. The Congress Street Grounds was a new double-decked ballpark designed to seat 14,000 people, located a short walk from Boston’s central business district.8

Many of the ballplayers signed by the Boston Brotherhood club jumped their contracts with the Boston NL team, led by the highly popular Kelly. This exodus created a superior product to attract baseball fans to the Brotherhood games played at the Congress Street Grounds, in comparison to the diluted product fielded by the Boston NL team. The Congress Street Grounds was a new double-decked ballpark designed to seat 14,000 people, located a short walk from Boston’s central business district.8

The Boston Brotherhood club outdrew its crosstown NL rival during the 1890 season, if reported attendance can be believed. Both Boston clubs fudged their attendance figures, either by rampant distribution of complimentary tickets or by exuberant inflation of turnstile counts. The accepted season attendance numbers show that about 50,000 more people attended the Brotherhood games in Boston (197,000) than the NL games (147,000). The Boston Brotherhood team cruised to the pennant in the first and only year of the Players’ League.

As the epicenter of professional baseball in Boston during the first half of the 1890 season, the Brotherhood club was able to raise an additional $10,000 in capital in August of 1890 through a supplemental offering of 100 shares of stock.9 W.H. Keyes, the contractor who built the Congress Street Grounds, was the largest new stockholder, buying 25 shares, while Prince added 20 shares to his initial 5-share stake to now hold 25 shares.10 Prince and Keyes were now the third largest stockholders. Neither Dixwell (with 35 shares) nor Hart (with 28 shares) purchased any shares in the supplemental offering, so the ownership interest of these two largest stockholders declined to 12 and 9 percent, respectively, with 300 total shares now outstanding.

At the October annual corporate meeting of Boston Brotherhood club, Prince was elected president, Hart re-elected secretary, and Irwin was named treasurer to replace Long; the stockholder directors were Prince, Dixwell, Haynes, and Timothy Daly and the ballplayer directors were the existing slate except that Nash replaced Irwin (now an officer).11 The four stockholder directors held a combined 87 shares, or 29 percent of the 300 shares.12

The Boston Brotherhood club was reportedly the only Players’ League club to make a profit in 1890. Prince announced at the annual meeting that “the report of the treasurer showed the club to be in an excellent financial condition.”13 The actual tabulated profit turned out to be a scant $138, on a cash accounting basis, after expensing the $41,486 in construction costs to build the Congress Street Grounds.14

Prince now headed an organization that seemed capable of toppling the venerable Boston NL club. “Had the Boston Players’ League club only been competing against the local National League club, it may have forced it out of business,” this author noted in his book Red Sox vs. Braves in Boston: The Battle for Fans’ Hearts. “However, the PL club was competing against the cartel of National League owners, who were bound and determined to destroy the Players’ League and do whatever was necessary to save the National League.”15 Unfortunately, profit-maximizing capitalists controlled most of the Players’ League clubs (Boston being the notable exception), which made them easy targets for a buyout by the NL or ascension into NL ownership. From the ballplayers’ perspective, the capitalists betrayed the worker ideals of the Players’ League.

To fight against the National League, Prince, who considered himself a budding magnate and not a mere lawyer, became president of the Players’ League in November of 1890.16 One month later, in December, when prospects faded to keep the Players’ League alive, Prince arranged for the transfer of the Boston Brotherhood club to the American Association, a major league that was on its last legs.

While Prince negotiated with a joint conference committee of and AA officials, he and Dixwell bought out the shares of many smaller investors in the Brotherhood club. In November the Boston Globe reported that Dixwell and Prince were the largest stockholders in the Brotherhood club, with Dixwell having “$10,000 sunk in this scheme,” which would represent 100 shares.17 By early January of 1891 the Globe noted that “Dixwell has disposed of his stock in the local P.L. club to President Charles A. Prince.”18 At this juncture, Prince owned at least a plurality of the stock and may have held more than 50 percent of the stock for a majority ownership position. Dixwell returned to being the best-known baseball fan in Boston. In 1901 he assisted the Boston club in the new American League to successfully unseat the monopoly of the Boston NL club.19

In mid-January of 1891, as part of the deal for Prince to abandon his demand for an expensive buyout of the Boston Brotherhood club, the Boston NL club agreed to accommodate its transfer to the American Association, under four conditions: (1) all former ballplayers of the Boston NL club had to be returned to the control of the NL club, (2) admission to the Boston AA games had to be 50 cents (the same as for NL games), (3) the Boston NL club exclusively had the home games on the Decoration Day holiday (the AA club had the less lucrative Independence Day games), and (4) the Boston AA team could not bill itself as “Boston,” but rather “must have a distinct name, like the Blues.”20

Prince agreed to abide by all the stipulations made by the rival Boston NL club. The name “Reds” was chosen to identify the Boston AA club, which Prince hoped would rekindle fond memories of the old Boston Red Stockings club of the 1870s. As it turned out, the Boston NL club was most interested in retaining the services of Kelly (although he balked at returning), so several players on the Brotherhood team returned to play for the Boston Reds in 1891.

Both contemporary and modern-day research supports the proposition that the Boston Reds in the American Association were a continuation of the Brotherhood club in the Players’ League. “The Boston people said that it was folly to refuse to allow the Association club a berth in Boston,” the New York Times reported in January of 1891. “The Players’ League team of that city was immediately elected a member of the Association.”21 Economic historians James Quirk and Rodney Fort report that the genesis of the Boston club in the Association was that the team “moves into AA from PL in PL-AA-NL agreement.”22

Prince was the acknowledged singular owner of the Boston Reds during the 1891 season, apparently having a controlling interest in the club’s stock, as newspapers rarely reported the existence of other officers or directors. By August Prince did have “considerably more than a controlling interest” in the Boston Reds, when he resigned as president and was succeeded by Hart to administer Prince’s interest for the remainder of the season.23

Despite the original agreement not to undercut NL admission prices, Prince implemented a 25-cent admission policy at the Congress Street Grounds for the game on July 18, since he believed “it pays to cater to the masses.”24 In August the “popular prices” were instituted for the team’s remaining home games. The Reds won the championship of the American Association and attracted 170,000 spectators in 1891, just a few thousand customers short of outdrawing the rival NL club (184,000 in attendance).

Hart became vice president of the American Association after the season was over, as he tried to salvage that organization as a viable major league. When his efforts failed, he left baseball to focus on his business interests. Hart died on September 17, 1939, in New York City and is buried near Boston.25

With the impending demise of the American Association, Prince negotiated hard to salvage some value from his stock investment in the Boston Reds, as he sought a $50,000 buyout of the Boston ballclub.26 In early December he gave up the fight. “I am sick of the sport,” Prince wrote in a letter to his AA comrades. “I have not the time or inclination to continue this war, knowing the disasters that must follow. A change must come, and the sooner the better for those with money invested, as well as for the future prosperity of the national pastime

On December 17, 1891, an agreement was reached for the AA to merge into the NL, with four AA clubs to transfer into the NL and the Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia clubs to be absorbed by the NL clubs in those cities.28 Prince accepted a financial settlement of $37,500 for the Boston Reds, to be paid from a fund raised from all the NL club owners, not solely by the Boston NL club.29 “Prince was one of the wise ones who saw what was coming and decided to sell out,” the Boston Daily Advertiser reported, “which he did at an extremely low price.”30 The settlement included the grandstand at the Congress Street Grounds and the existing lease for the underlying land, owned by the Boston Wharf Company.

Before the Boston Reds stockholders could be paid, though, Prince had to round up the stock certificates of all 300 shares to transfer them to the NL fund. On January 9, 1892, when only 267 shares could be collected, the NL fund paid Prince “$30,000 in long-term notes, holding back $7,500 until all the stock is turned in,” according to a Boson Globe report, which noted, “of this money, Mr. Prince will take out what the club owes him personally, said to be close to $30,000.”31

Prince’s speculative stock investments included not just the Boston Brotherhood/Reds ballclub but also railroad stocks. With his delusions of grandeur, Prince embezzled an estimated $1 million from friends and family in an attempt to profit on the merger of his employer, the New York & New England Railroad, with the competing Boston & Maine Railroad before those merger prospects collapsed in May of 1893.32 Prince left the United States in disgrace and lived the rest of his life in exile on the island of Noirmoutier, off the coast of France, until his death in 1942.33

CHARLIE BEVIS is the author of seven books on baseball history, most recently “Red Sox vs. Braves in Boston: The Battle for Fans’ Hearts, 1901–1952” (McFarland, 2017). A member of SABR since 1984, he has contributed more than five dozen biographies to the SABR BioProject as well as several to SABR books. He is an adjunct professor of English at Rivier University in Nashua, New Hampshire.

Notes

1 Abstract of the Certificates of Corporations Organized Under the General Laws of Massachusetts During the Year 1889 (Boston: Wright & Potter, 1890), 6.

2 Robert B. Ross, author of The Great Baseball Revolt: The Rise and Fall of the 1890 Players League, has graciously shared a complete list of stock ownership (beyond the details in his book) from his notes taken of the records in the Frederick Long Papers at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown.

3 “Players Organized; Boston’s New Club Elects Officers,” Boston Globe, November 30, 1889; “Director Hart Returns Unsuccessful,” Boston Globe, February 11, 1890; “Off the Diamond,” Boston Globe, April 21, 1890. The fourth nonplayer director likely was Dixwell, who had the largest stock holding.

4 “Our New Nine,” Boston Daily Advertiser, December 2, 1889.

5 Robert B. Ross, The Great Baseball Revolt: The Rise and Fall of the 1890 Players League (University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 98; stock holding of Prince is from the stock list in the Frederick Long Papers.

6 Stock list in the Frederick Long Papers.

7 “Against the Triumvirs,” Boston Globe, December 22, 1887; John C. Haynes et al vs. Boston Base Ball Association, “Court Calendar: Supreme Judicial Court — Oct. 6,” Boston Daily Advertiser, October 8, 1888.

8 “New Grounds of Players’ League Club,” Boston Globe, December 11, 1889.

9 Ross, The Great Baseball Revolt, 100.

10 Stock list in the Frederick Long Papers. Mysteriously, Long’s list accounts for only 85 of the 100 new shares purchased.

11 “Directors Were Pleased,” Boston Globe, October 21, 1890.

12 Stock holdings of the four directors (initial + supplemental = total): Prince (5+20=25), Dixwell (35+0=35), Haynes (9+10=19), and Daly (5+3=8).

13 “Boston P.L. Club Meets,” Boston Daily Advertiser, October 21, 1890.

14 Frederick Long Papers, quoted in Ross, The Great Baseball Revolt, 184.

15 Charlie Bevis, Red Sox vs. Braves in Boston: The Battle for Fans’ Hearts, 1901-1952 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017), 37.

16 “Charles A. Prince Elected President of the Players’ Organization,” Boston Globe, November 12, 1890.

17 “The Three Bell Wethers,” Boston Globe, evening edition, November 13, 1890.

18 “Base Ball Notes,” Boston Globe, January 11, 1891.

19 Bevis, Red Sox vs. Braves in Boston, 57-58.

20 “Two Clubs Here; Papers Are Signed and Boston Is in the Association,” Boston Globe, January 17, 1891.

21 “End of the Baseball War; The Players’ League Practically Dead, and the Association at Last Secure[s] the Desired Franchise in Boston,” New York Times, January 17, 1891.

22 James Quirk and Rodney Fort, Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Sports (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 383.

23 “New Head for Association,” Boston Globe, August 6, 1891.

24 “Reduced the Price; Twenty-Five Cents Each for the Next Two Games,” Boston Globe, July 18, 1891.

25 Death notice, New York Times, September 18, 1939; “Live Tips and Topics,” Boston Globe, September 20, 1939; records of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts (Glen Avenue, Lot 5759).

26 “Baseball Magnates Struggling with the Peace Problem,” Boston Globe, December 17, 1891.

27 “Plot and Counterplot; Prince Sick of Fighting the National League,” Boston Globe, December 14, 1891.

28 “Baseball Consolidation: A Single National League with Twelve Clubs to Be Formed,” New York Times, December 17, 1891.

29 “Champions Sold; Boston Reds Disposed of for $37,500,” Boston Globe, December 18, 1891.

30 “New Baseball League,” Boston Daily Advertiser, December 31, 1891.

31 “Mr. Prince Receives the First Payment,” Boston Globe, January 10, 1892. Since it is unknown what he paid Dixwell and the smaller investors for their stock positions, it is unclear if Prince made or lost money on his investment in the ballclub.

32 “Mr. C.A. Prince: His Absence Likely to Be a Long One,” Boston Daily Advertiser, June 3, 1893; “Prince Exiled: The Ex-Magnate Will Never Come Back to America,” Sporting Life, July 22, 1893.

33 Alumni file of Prince in the Harvard University Archives.