Kansas City Royals team ownership history

This article was written by Daniel R. Levitt

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

Over its first five decades, the Kansas City Royals have had only three ownership regimes. Pharmaceutical entrepreneur Ewing Kauffman landed the Royals expansion franchise for the 1969 season and believed that the team could and should be competitive in a previously unprecedented time frame. He was willing to innovate and spend to boost the Royals chances of swiftly building a championship squad, and while it took longer than expected to win that first pennant, the Royals were soon recognized as a model franchise. Twenty-four years later, when he couldn’t find a local buyer, Kauffman set in motion an arrangement that upon his death contributed the team to a local charitable foundation to make sure it remained in Kansas City.

A board named by Kauffman ran the franchise — unsuccessfully on the field — for roughly six years before David Glass, the head of the board, purchased the team outright. For the first decade of his ownership, the on-field woes and meager payroll generally lingered, and Glass remained a strident spokesman on behalf the of small-market teams. Eventually, the youth movement that had moved forward in fits and starts was reinforced with higher-priced veteran talent, and the Royals won back-to-back pennants in 2014 and 2015.

The Royals came into existence as the American sports landscape was shifting. After decades of stability, the 1950s and ’60s saw a flurry of long-standing baseball teams moving to new cities and baseball expanded three times, adding two AL teams in 1961, two NL teams in 1962, and two in each league in 1969. The 1969 expansion was precipitated when Charlie Finley moved the Kansas City Athletics to Oakland in October 1967. Facing legal pressure, the American League responded by awarding franchises to Kansas City and later Seattle. Unlike more recent expansions in the 1990s, baseball chose the cities first, and then searched for ownership groups.

Four groups presented to the American League’s owners at the December 1967 winter meetings. Alex Barket, president of Civic Plaza National Bank, proposed individual ownership, with Tudie Patti, vice president of the Metropolitan Construction company, in a subordinate role. Another bidder was a syndicate headed by John Latshaw, vice president of E.F. Hutton & Co., who offered two different possible ownership structures, depending upon the owners’ preference. A third group was led by Richard Stern, president of Stern Brothers, an investment bank, and Crosby Kemper, retired chairman of City National Bank. Stern and Kemper planned to sell up to 75 percent of the team’s ownership to the public. The fourth entry and putative favorite was Ewing Kauffman, founder and head of Marion Laboratories, a Kansas City-based pharmaceutical company.1

On January 11, 1968, the league announced that it was awarding the team to Kauffman. “I’ve always said it was the greatest trade in the history of baseball [getting Kauffman instead of Finley as the city’s franchise owner],” said sportswriter Joe McGuff.2 The Royals initially cost Kauffman roughly $6 million: $5,250,000 for the players taken in the expansion draft, $50,000 for the franchise rights, and roughly $600,000 to the players pension fund. Of course, there were also many other costs associated with starting a franchise. Kauffman estimated that he would spend $200,000 to $300,000 operating the club in 1968 without any incoming revenue. Overall, “We expect tax losses of $1.8 million,” Kauffman said, “but once we get in the new stadium I anticipate we will improve our operation.”4

On January 11, 1968, the league announced that it was awarding the team to Kauffman. “I’ve always said it was the greatest trade in the history of baseball [getting Kauffman instead of Finley as the city’s franchise owner],” said sportswriter Joe McGuff.2 The Royals initially cost Kauffman roughly $6 million: $5,250,000 for the players taken in the expansion draft, $50,000 for the franchise rights, and roughly $600,000 to the players pension fund. Of course, there were also many other costs associated with starting a franchise. Kauffman estimated that he would spend $200,000 to $300,000 operating the club in 1968 without any incoming revenue. Overall, “We expect tax losses of $1.8 million,” Kauffman said, “but once we get in the new stadium I anticipate we will improve our operation.”4

Kauffman’s earlier lobbying and natural sales skills helped him in winning over the owners. More important, perhaps, were his demonstrated financial capabilities and his stated intention to own the franchise himself. When asked about his connection with gambling due to his racehorses, Kauffman stated that he never bet on baseball or football, and earned a chuckle when he said he would continue to gamble but only at golf and cards.

Kauffman had both the net worth and the liquidity necessary to purchase and bankroll an expansion franchise. Marion Laboratories had a market value of roughly $156 million, and Kauffman and his family owned 31 percent of the company.5 Moreover, he had become a sportsman in the old-fashioned sense of the word, owning a stable of several racehorses and enjoying the associated lifestyle. Sportswriter and local booster Ernie Mehl had pushed Kauffman to pursue the franchise, telling him, “We need to show the American League there is somebody in Kansas City that is somewhat interested in baseball and financially can afford it.”6 With encouragement from his wife, Muriel, Kauffman entered the sweepstakes to own Kansas City’s expansion team.

With his typical forethought, Kauffman had traveled to Anaheim to meet with California Angels owner Gene Autry and team President Bob Reynolds, who had been through the process with their 1961 expansion team. While on the trip, Kauffman also met Cedric Tallis, an Angels executive who greatly impressed him. As Kauffman finalized his bid for his team, he invited Tallis to join his group as its general manager. Kauffman not only thought Tallis a smart baseball man, but liked that he had been the principal executive overseeing the creation of the Angels’ new ballpark.

Like many successful owners, Kauffman could be highly demanding, both publicly and privately. Yet he was one of the few also celebrated by the community and his players for his generosity and obvious care for their well-being. His compelling personality along with his ability to connect with a diverse range of individuals made him one of baseball’s more beloved owners.7

Kauffman grew up on a farm just southeast of Garden City, Missouri. After some tough years farming, the family moved to Kansas City, where his father’s sisters and parents helped them buy a house. When he was 11, Kauffman was diagnosed with endocarditis, a heart ailment, for which the treatment at the time was absolute bed rest for an entire year. As awful as this must have been for a young boy, Kauffman read up to 20 books a week and learned to quickly perform complicated mathematical calculations in his head. He recovered fully and later played football in high school. Kauffman also exhibited an early aptitude for sales. During World War II, Kauffman joined the US Navy, where he excelled as a navigation officer. His service time was also extremely profitable. Over his enlistment he won roughly $90,000 playing poker and would often send a large percentage to his wife to save for after the war.8

By this point Kauffman had matured into an interesting, complex individual. He was extremely competitive, hardworking, and driven, and very much believed in people having to earn their rewards. But he also was generous and caring. His extraordinary sales skills came from the former tempered by his obvious openness and genuineness in wanting to help the clients he was selling to.

After taking a job as a pharmaceutical salesman after the war, Kauffman decided to strike out on his own. In June 1950 he took what remained of his savings and launched Marion Laboratories. Though it didn’t have any research capabilities at the time, Kauffman imagined that “Laboratories” added a gravitas to the corporate name. He built a solid management team to support his sales staff, and the company prospered throughout the 1950s: By 1959 Marion achieved $1 million in annual sales. In February 1962 Kauffman married for a second time, tying the knot with Muriel McBrien. Muriel would become a force in her own right in the Kansas City community.

As the company flourished in the early 1960s, Kauffman wanted to take it public to bring in additional capital and create liquidity for his shares and those of many of his longtime employees. By 1965 company revenues were almost $5 million and net income had surpassed the $500,000 target set by his investment bankers. Initially, the company went public as over-the-counter stock, eventually listing on the New York Stock Exchange in 1969.

While pursuing the franchise, Kauffman told the owners he would bring in professional management, just as in his pharmaceutical business. Tallis, awarded a four-year contract and with a new major-league team to build, received the same memo. “Outside of finances, he will run the club,” Kauffman told reporters.9

“Kauffman did not dabble in day-to-day team management,” wrote his biographer. “He had decided early in his involvement with baseball that he would either have to trust the executives he hired or fire them. That had been his policy at Marion Laboratories, where he understood the pharmaceutical business.”10 That said, Kauffman would get involved if he felt he needed to. To increase ticket sales, he mirrored his Marion sales-recognition programs on the baseball side, creating an exclusive booster club with high-test perks for local businessmen who sold at least 75 season tickets.

At the ballpark he was equally attentive. “I’d have taken out the kid [Hedlund] and brought in Moe [Drabowsky] a little sooner than [manager] Joe [Gordon] did,” Kauffman remarked after one game in 1969. After learning that Drabowsky wasn’t “completely warmed up,” Kauffman backpedaled, “That’s why he’s the manager and I’m the owner.”11 But he remained attentive and unafraid to demand explanations from his senior management.

Though Kauffman allowed his baseball men to build his team, he was unafraid to think unconventionally and push to implement his ideas. He kept a copy of Earnshaw Cook’s Percentage Baseball on his desk, the first serious statistical look at the game written by an outsider. He even followed up by meeting with Cook to discuss his concepts. Kauffman also introduced one of baseball’s first computer systems, which by the end of the 1971 season contained statistics like “the nature of every pitch thrown by a Royal … what happened to every ball hit … [and] even the humidity.” One writer who witnessed Tallis and his staff reviewing some of this information exclaimed: “I felt I had walked in on a conclave of madmen. Here were six or seven grown men around a table piled high with computer cards, mulling over every pitch thrown and every ball hit in what is supposed to be a game.” This information was fed to the manager so that it could be applied. Thirty years before Michael Lewis wrote Moneyball, Kauffman believed that statistical analysis could provide a competitive advantage when added to traditional evaluation methods.12

Kauffman also had new ideas on how the team should find talent. He had publicly stated that he wanted a pennant within five years, a wildly aggressive prediction given the history of the four previous expansion franchises. To accomplish this goal, Kauffman realized that the usual methods of finding young players would not be sufficient: The amateur draft offered all teams equal access to top prospects, Latin and Caribbean countries were being scouted (though untapped opportunity was later to be uncovered there), and Japan was not yet considered a source for major-league players.13

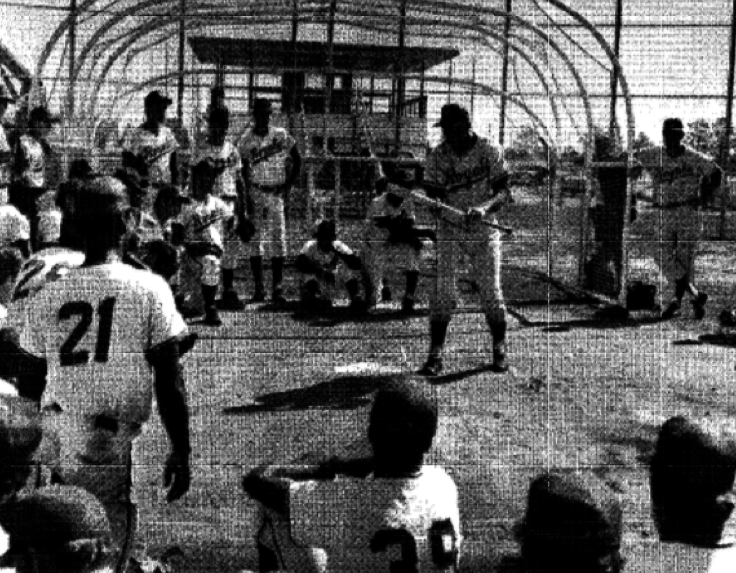

Kauffman’s brainstorm was to create the Kansas City Baseball Academy, a school operating outside the traditional farm system at which undrafted athletes with little baseball background could learn the game. Kauffman’s academy applied a scientific approach to scouting and training: Figure out which raw skills best translated into baseball success and then how to best develop and hone those skills to create ballplayers. To house it, Kauffman purchased a 121-acre site in Sarasota, Florida. The complex cost roughly $1.5 million and required a further $600,000 or so in annual operating expenses.

Kauffman took a direct, personal interest in the Academy. When he heard that prospective prospects were not given an eyesight test, he went out and brought in specialists to help develop tests.14 Kauffman took special interest in what skills were needed to make a great hitter and how to enhance those skills. After testing established players in his own organization and a few other stars such as Johnny Bench, Pete Rose, and Tony Perez, Kauffman said, “We have boys in the academy who have faster reaction times than Bench, but his ability to track a moving object is the most tremendous that any of us have ever seen. … I think the ability to track an object can be taught and improved on and we will have classes to teach this.15

In mid-June 1971 the Academy faced its first public test when a team of its cadets was placed in the seven-team, rookie-level Gulf Coast League, pitting the recruits against drafted ballplayers in other organizations. The team finished 40-13 and led the league in batting average and ERA. This early validation of his concept was one of Kauffman’s greatest thrills in baseball.

Jim Lemon demonstrates bunting at the Kansas City Royals Baseball Academy in the late 1960s. (THE SPORTING NEWS)

Yet the Academy had detractors within the organization, as many in the front office begrudged the huge allocation of resources to something outside of their traditional farm system, which in tandem had built a first-rate scouting and development system. By 1973, while the Academy had produced several prospects, it had become clear that Kauffman’s brainchild needed to be revamped. The Royals’ original thesis — that great young athletes with little baseball background could be molded into major-league baseball players — had not proven out. Despite all its creative ideas and intense testing, the Academy could not create enough ballplayers from raw, unskilled athletes. The top prospect in the Academy, infielder Frank White, had significant previous baseball experience. The other noteworthy problem with the Academy was the huge cost. When Marion Laboratories stock collapsed during 1974 due to the recession and concerns over forthcoming FDA approval for a new drug (between February and August the stock price dropped from $52 per share to $11), Kauffman decided to shutter the academy and integrate its facilities into the overall minor-league system.16

Nevertheless, Kauffman felt that the Academy was to some degree succeeding at its mission and grew nostalgic over time that it could have offered a fresh source of players. He would later say his greatest regret in baseball was closing the Academy. “If I knew then what I know now,” Kauffman later lamented, “I would have kept it going. And we would have had a dynasty here. It really worked.”

That the Academy did not succeed in turning multiple-sport athletes into major-league-quality baseball players testified to the fact that traditional scouting was already finding most — though not all — of the potential major leaguers in the US. However, Kauffman’s philosophy of always looking for new sources of talent is one of the foundations of successful organizations. Of the Academy’s innovations in scouting and player development, some were transferred to the Royals farm system and many others were carried by the Academy’s coaches and trainers as they migrated within the organization and to other teams. Like most successful organizations, Kauffman’s Royals showed a sincere willingness to experiment with new ideas and methods. As a result, they found a few valuable players and learned useful player development and scouting lessons.

Kauffman had benefited from one of Finley’s constant complaints, an inadequate municipal stadium, a complaint echoed by football’s Kansas City Chiefs. By the mid-1960s, the civic leadership recognized that they would need something better than Municipal Stadium to house the football Chiefs and a major-league baseball team. With the fanfare over the Astrodome in Houston, initial designs contemplated a multipurpose domed stadium. As concerns about the design and costs grew, however, the current layout of two stadiums within one complex began to take shape, and in 1967 a bond issue was approved to finance their construction. The original plans included a rolling roof, which eventually was dropped due to cost overruns and construction delays.18 The $43 million sports complex was scheduled to open in 1972. To accommodate the team until the new stadium was ready, Kauffman signed a lease at Municipal Stadium.19

Within a couple of years, Kauffman was taking a financial hit on the new ballpark, which was costing more than expected, some of which he needed to cover. Revenues were also hurt for a year as construction delays deferred the opening until 1973, and attendance in 1972 fell to just over 700,000. It would jump to a then-team record 1,345,341 in 1973, the Royals’ first year in the new ballpark.

The 1972 season was marred by a players strike that began during spring training and lingered into the season, canceling a week’s worth of games. As the players union had never taken such an action before, the events stunned many longtime baseball people, and Kauffman developed into a semi-hawk on player issues. He was a paternalistic owner in the best sense of the word, offering free career counseling and financial advice to his players and occasionally handing out hundred-dollar bills to players in the locker room after a tough game, telling them to take their wives out for dinner.20 But Kauffman had spent a lot of money to acquire and build the franchise, which was still not profitable, stating that he had invested roughly $19 million in the franchise: Beyond the initial investment, he had sunk $5 million into Royals Stadium and annual losses were significant. For example, in 1971 the team lost $2.2 million; $600,000 was depreciation, a noncash charge, but the other $1.6 million was operating losses.21 Kauffman couldn’t see why the players should be allowed any more of the overall baseball revenues.

In response to Marvin Miller and the players association filing to arbitrate the McNally–Messersmith challenge to the reserve clause in the fall of 1975, Kauffman filed suit, supported by the other major-league clubs, arguing that the reserve clause was not arbitrable under the collective-bargaining agreement. The court allowed the arbitration to move forward, telling Kauffman he could come back if he wanted to dispute the decision. When Kauffman led the owners back into court to overturn the famous Seitz decision that invalidated the reserve clause, the court ruled that the arbitrator’s ruling would stand. Kauffman’s frustration with free agency can be seen in his reaction to it: Through 1980 the only free agent signed off another team was utility infielder Jerry Terrell.

On the field, the Royals backslid in 1972 after a surprising 1971 season, and the impatient Kauffman decided to fire manager Bob Lemon over Tallis’s objections. As justification, Kauffman publicly mentioned a mishandled August benching of Amos Otis and Freddie Patek for not hustling and also suggested that he wanted to hire someone younger. This last comment exposed Kauffman to age-discrimination protection, causing him to have to pay Lemon an extra year’s salary. Kauffman’s impatience and unrealistic expectations were also laid bare. “Starting in 1974,” he bragged, “we expect to win (the American League championship) five out of ten years.”22

Kauffman further exasperated Tallis by hiring Jack McKeon, the manager at Triple-A Omaha, with whom Tallis had quarreled in the past. In particular, McKeon was a vocal advocate for the Baseball Academy, and hence a favorite of Kauffman’s. McKeon would go on to a successful career in baseball as both a manager and general manager, but in 1972 he owed his allegiance to Ewing Kauffman alone. The impatient Kauffman had journeyed a long way from the putatively hands-off owner of 1969.

Despite a strong second-place finish in 1973, principally due to a number of great trades and smart drafting by Tallis and the front office, Kauffman became frustrated with his mounting financial losses. Between the financial drain of the Academy and the Royals’ top-notch minor-league system, the team reportedly lost hundreds of thousands of dollars annually. Notwithstanding a strong season on the field, the opening of their new ballpark, and a near-doubling of attendance, Kauffman lost roughly $900,000 in 1973.23 Late in the season he hired Joe Burke to run the financial side of the Royals to help stem the red ink. Burke had spent years in the front office of the Washington Senators and, after the club’s move to Texas, two years as the club’s GM. Kauffman was clearly preparing for a change in his GM.

Municipal Stadium served as home of the Kansas City Royals from 1969 to 1972. (COURTESY OF THE KANSAS CITY ROYALS)

By the middle of the 1974 season, as the Royals hovered near .500, “Kauffman’s irritation with the costs of owning a baseball team was beginning to show.”24 He had sunk somewhere around $20 million into the club and had yet to turn a profit in any season, and his net worth was sinking due to the Marion stock slide. Kauffman bounced Tallis and promoted Joe Burke to general manager, giving him full control over both the baseball and business sides. In another cost-saving move, after the season Kauffman directed Burke to join the newly formed Major League Scouting Bureau, enabling the Royals to lay off 20 full-time and 50 part-time scouts.25 A couple of years later, as the impact of this decision began to be felt in the farm system, Kauffman reversed course and began rebuilding his scouting staff. As with the sales employees at Marion, he offered the Royals scouts better perks and profit-sharing, but they “were expected to generate more leads and baseball talent than [their] rivals.”26 In late July 1975 Burke and Kauffman again changed managers, firing McKeon and bringing on Whitey Herzog. Herzog had managed for Burke in Texas and at the time was the third-base coach for the California Angels.

After four seasons of pursuing the Oakland A’s, in 1976 the Royals finally broke through with a 90-72 record and won the division title before losing a tightly contested ALCS with the Yankees. Of the eight expansion teams that began play in the 1960s, the Royals attained and sustained success the quickest, and Kauffman’s willingness to hire good baseball people and put money into his team was a big reason.

The team won division titles in 1977 and 1978 as well, again losing to the Yankees in the ALCS both years. Despite his success, Kauffman and Muriel never really warmed to Herzog, and the manager felt as though he was tolerated only as long as he was winning. Once when Angels owner Gene Autry asked Muriel how his “old friend Whitey was,” she responded, “Who gives a shit?”27 After falling to second place in 1979, Kauffman and Burke jettisoned Herzog, bringing in Jim Frey. Under Frey in 1980 the team finally beat the Yankees in the ALCS to win the pennant. “That was my greatest thrill in baseball,” Kauffman remembered. “And the moment was made all the more memorable because it had come at the expense of the New York Yankees.”28

After a disappointing 1981 season, Kauffman promoted John Schuerholz to GM and Burke to president. The team still boasted a talented nucleus, led by third baseman George Brett, and remained competitive in the early 1980s. The Royals finally won the World Series in 1985, bolstered by three young pitching aces.

The Kansas City Royals celebrate their 1985 World Series championship after defeating the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games. (COURTESY OF MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL)

For Kauffman, 1981 was something of a watershed year. He turned 65 and had a tumor removed from his chest along with part of a rib. On the baseball front, the Royals slumped as Kauffman believed Frey lost control of his players (Burke replaced him with Dick Howser), and the long players strike began to sap baseball’s appeal for him.29

Kauffman began considering bringing in a partner willing to buy a 49 percent interest in the team with rights to acquire full ownership down the road. In January 1983 he signed a letter of intent with a man named Michael Shapiro, and for $100,000 granted him an option to buy 49 percent of the franchise, including the cable-television rights, for $11 million and requiring a $12 million letter of credit. Once the deal became public, local reporters began digging into Shapiro’s background. It turned out he had gone to high school in Kansas City and was now living in Los Angeles and rumored to be associated with Hollywood. After some investigation, Shapiro was apparently not the bigwig he advertised. It seemed he was merely working in the accounting department at one of the studios. And sportswriter Joe McGuff learned he had been involved with a rodeo, and “(Shapiro) had ruined it.” Kauffman canceled the deal when Shapiro could not come up with the required deposit by the February 16 deadline.30

Later that spring Kauffman cut a similar deal with Memphis real-estate developer Avron Fogelman, but this time without the cable television rights. The two stipulated the value of the franchise at $22 million, and Fogelman paid $11 million for a 49 percent interest. Kauffman retained an option to sell the remaining 51 percent to Fogelman between 1988 and 1991. If Kauffman had not sold by the end of that period, he would become obligated sell to Fogelman. In early 1988 the two recut the agreement. Fogelman paid $220,000 to bring his share up to 50 percent and Kauffman’s sale obligation went away; he could now remain a partner in the team indefinitely. Their partnership agreement was extended through 2012 with the provision that if Kauffman died before then, Fogelman could purchase his 50 percent for $11 million.31 His frustration with baseball’s economics blinded Kauffman — like many others — to the massive increase in franchise values that was about to occur.

As Kauffman aged, and with some of Fogelman’s purchase capital now infused into the team, the Royals became more willing to pursue free agents to maintain its competitiveness, particularly toward the end of the decade. But several high-profile signings — notably Mark Davis, Storm Davis, Kirk Gibson, and Mike Boddicker — did not live up to the hype.

In 1989 Kauffman found himself forced to reorganize his businesses. As the pharmaceutical industry evolved, Marion’s executive leadership team felt a merger with another drug company was required for its long-term survival. Kauffman hated to surrender control of the company he had built from his basement, but he acquiesced to the recommendation. Later that year Marion Laboratories merged with Merrell Dow, a subsidiary of Dow Chemical, to create Marion Merrell Dow and a nice but unwelcome payday for Kauffman. In 1988 Forbes estimated his net worth at $740 million, an amount certainly increased through the merger; now much of that was liquid as well.32

At the same time, Fogelman’s real-estate empire was unraveling in the commercial real-estate lending and liquidity crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Fogelman was under tremendous pressure from his lenders and needed his equity in the franchise to bail himself out. Fearful the franchise would get caught up in Fogelman’s messy finances and an out-of-town buyer would get Fogelman’s purchase option, Kauffman agreed to recut their deal again. Under the new agreement, Kauffman loaned Fogelman $34 million and effectively regained full ownership of the team. In addition he would have to cover roughly $20 million in failed real-estate investments awarded to players George Brett, Dan Quisenberry, and Willie Wilson, originally backstopped and advocated by Fogelman as part of their contract extensions. Moreover, Kauffman would have to fund $5 million to cover the previous year’s asset contribution defaulted on by Fogelman, and the entire $7 million in operating losses for the current year, typically split between the two partners. Not surprisingly, Kauffman said, “I feel like I have been taken advantage of.”33 Kauffman used the uncertainty created by Fogelman’s troubles to leverage a more attractive new 25-year lease on the ballpark and lock the team to Kansas City for the foreseeable future.

By the early 1990s Kauffman was aggressively spending on his roster while at the same time seething at the players union. In 1990 as the two sides battled over the collective-bargaining agreement, Kauffman said, “If they don’t settle soon, it would be my nature to withdraw everything offered and close the season down. You cannot keep giving and giving and giving.”34 Nevertheless, he still desperately wanted to win, and by 1993, after signing David Cone and Greg Gagne, Kansas City had the fourth highest payroll in the game.

Kauffman’s health had also begun to fail, and he began to fear for his mortality. He wanted to sell the team to a local ownership committed to keeping the team in Kansas City, but no one stepped up to the roughly $90 million price tag he hung on the franchise. Instead, he tasked Marion CFO and his longtime financial adviser Michael Herman to devise a structure that would allow the team to be owned in trust until baseball’s economics changed and a satisfactory buyer could be found who would keep the team in Kansas City.

Kauffman, Herman, and the tax lawyers eventually came up with a convoluted, tax-advantaged proposal. Upon his death, the team was to be donated to the Greater Kansas City Community Foundation. A five-person limited partnership would purchase Class A voting stock to run the team, and the foundation would receive Class B nonvoting stock. Kauffman also funded enough cash to cover annual operating deficits, estimated in excess of $3 million per year, and additional expenditures associated with free agents. As part of the bargain with the community, local leaders and charities would be required to come up with $50 million to help subsidize operating losses. When the team was eventually sold, they would get their money back. Kauffman also suggested reducing payroll to minimize losses until a buyer could be found and baseball’s economics recalibrated.35

Two potential stumbling blocks existed: the baseball owners and the IRS. Baseball’s owners did not want one of their franchises owned by a charitable foundation but eventually agreed as long as there was a deadline set as to when the franchise had to be sold. The tax issue came down to “whether retaining a baseball franchise in Kansas City is a charitable activity.” If not, the estate tax on the franchise might have forced an immediate sale. The alternative of donating the franchise to his Kauffman Foundation would have been problematic due to the limitations on the use of the foundation’s charitable funds to cover operating losses on a noncharitable entity and the prospect that the foundation would be required to quickly sell to the highest bidder. In 1995 the tax authorities affirmed that the transaction was, in fact, tax-exempt. The foundation would have six years to sell the team, after which a buyer would not be required to keep the team in Kansas City.36

Kauffman died on August 1, 1993, from bone cancer. He had a private funeral and burial three days later. A month before his death, Royals Stadium was renamed Kauffman Stadium in his honor. The franchise was turned over to the five-person limited partnership of Kauffman’s handpicked members. Longtime friend and Walmart CEO David Glass, whom Kauffman had first met years earlier when he was still actively engaged in pharmaceutical sales and calling on Glass’s drugstores, became managing partner.37 The other four partners were Herman, who became team president; Lou Smith of the Kauffman Foundation and president of the Kansas City office of Allied Signal; Larry Kauffman, Ewing’s son; and Gene Budig, chancellor of the University of Kansas. When Budig was named AL president in June 1994, McGuff took his spot. Glass paid $250,000 for his controlling shares, the other five paid $50,000 each. Under IRS rules, these Class A shareholders were limited to a profit on their investment not to exceed 15 percent per year.38

Kauffman died on August 1, 1993, from bone cancer. He had a private funeral and burial three days later. A month before his death, Royals Stadium was renamed Kauffman Stadium in his honor. The franchise was turned over to the five-person limited partnership of Kauffman’s handpicked members. Longtime friend and Walmart CEO David Glass, whom Kauffman had first met years earlier when he was still actively engaged in pharmaceutical sales and calling on Glass’s drugstores, became managing partner.37 The other four partners were Herman, who became team president; Lou Smith of the Kauffman Foundation and president of the Kansas City office of Allied Signal; Larry Kauffman, Ewing’s son; and Gene Budig, chancellor of the University of Kansas. When Budig was named AL president in June 1994, McGuff took his spot. Glass paid $250,000 for his controlling shares, the other five paid $50,000 each. Under IRS rules, these Class A shareholders were limited to a profit on their investment not to exceed 15 percent per year.38

David Glass had loved baseball since his youth and would now be running a big-league team. He had worked his way from a small-town Midwestern boy to become the CEO of Wal-Mart, America’s largest retailer. Author Bob Ortega described his approach: “Glass veiled his driving ambition and his great confidence in his own abilities behind a cool, deliberative, and circumspect manner.”39

Glass grew up in Mountain View, a town of a few thousand in southeastern Missouri. Like most kids at that time and place, he worked to help support the family while he went to school. Glass was not a particularly driven high-school student but showed a strong aptitude for math. He played multiple sports, including baseball, and became a huge Cardinals fan. After a couple of adventures post-high school, Glass joined the Army and married Ruth Roberts. After his stint in the military, Glass enrolled in Southern Missouri State University in Springfield, where he received a degree in business administration. Marriage, the Army, and college seemed to have focused his ambition, and after college Glass joined Crank Drugs, a Springfield-based drugstore chain.40

Glass first met Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton in 1964 at the grand opening of one of Walton’s early stores. Walton had heard good things about Glass’s financial abilities at Crank and invited Glass to the event. The gala turned into a farce when watermelons stacked outside started exploding in the 115-degree heat and the juice began mixing with excrement from the donkeys brought in to give rides to children. The mess and the stench became part of Wal-Mart lore. Not surprisingly, Glass shied away from Walton’s approach.41

As Wal-Mart expanded over the next decade, Walton continued to keep an eye on Glass. Finally, in 1976 when Walton offered him the role of executive vice president of finance and distribution, effectively the number-four position at the company, Glass accepted. Over the next several years Glass became CFO, and finally, in 1988 he was named CEO.

When he became CEO, Glass moved the company beyond simply better merchandising and expense control to propel Wal-Mart’s expansion. “I guess the single biggest difference between my approach and [Walton’s],” Glass said, “is that a long time ago I had strong belief that technology would ultimately drive this business to be the size that it is. I’ve championed our efforts in technology and the systems and sophistication that we’ve been able to achieve, everything from the logistics aspects to all the financial aspects of it.”42 By the time he retired 12 years later, the company had grown from 1,200 Wal-Mart discount stores to about 2,500, plus 456 Sam’s Club warehouses, and another roughly 1,000 stores worldwide. Sales had increased from $16 billion to $165 billion.43

As the 1980s drew to a close, Glass’s net worth (estimated at $400 million to $500 million in 1991) had grown well beyond the amount needed to comfortably buy a baseball franchise, and he was searching for one to either buy or invest in. In this pursuit Glass made unsuccessful runs at the Royals, Minnesota Twins, and San Diego Padres. In 1991 Glass was part of an investment group led by longtime St. Louis GM Bing Devine and Walton, who were trying to buy the Houston Astros. Owner John McMullen reportedly targeted a $100 million price, and Devine’s group couldn’t forge a deal. Coincidentally, McMullen sold the team the next year for $117 million to Drayton McLane Jr., who had sold his grocery wholesale business to Wal-Mart in 1990.44

Once he became chair of the Royals board, Glass declared he did not plan to meddle in the baseball operation. “I get to do the fun part of it. I get to say yes or no on important decisions. Being a baseball fanatic for all of my life, I do have fun with it. But it doesn’t require much time.” 45

Glass quickly became a hawk on labor matters and a strong proponent of revenue-sharing. He rationalized his aggressive support of revenue-sharing by highlighting the difference between baseball and other businesses: “In business you go out and do the best job you can and you don’t have to worry about competitors. Whoever does the best job wins. But in professional sports, you have to worry about your competitors. You want to beat your competition, but you also want to make sure you keep them strong.”46

Glass was instrumental, for example, in gaining August Busch III’s reversal and acceptance of revenue-sharing in early 1994. Glass was one of the owners who urged Busch to change his mind. Several of these men, including Glass, had leadership positions with the beer company’s largest customers. When Busch changed his position, one writer noted this relationship between Busch and men who called him. “Gosh, I don’t deserve any credit for it,” Glass said, playing his role down. “St. Louis deserves the credit for bringing in fresh proposals.”47

Though Kauffman’s legacy had accounted for operating deficits by creating a pool to fund them, the Glass-led partnership was extremely frugal with its spending so as not to risk depleting the reserve. The front office felt outfielder J.D. Drew was the best player in the 1998 draft but did not select him due to financial constraints. Players either traded away or allowed to leave as free agents because of salary concerns included David Cone, Tom Gordon, Jose Offerman, and Tim Belcher.48

In the aftermath of the 1994-95 strike, the board realized they would have difficulty finding a purchaser willing to pay a reasonable price and hesitated to put the team formally on the market. In the meantime, they were approached by a group led by George Brett and his brothers. Brett, who had retired after 1993 as a future Hall of Fame third baseman and the greatest player in Royals history, was now director of player development for the Royals and a fan favorite. When he “made some commotion about wanting to see the books,” some in the community felt he wasn’t getting fair shake.49 In fairness to the board, they reportedly couldn’t engage in a sale of the team without a formal marketing process and hadn’t yet even engaged an investment banker.50

Glass was a logical buyer and several people close to Kauffman, including his daughter Julia, thought he wanted Glass to eventually buy the team.51 Glass’s interest in baseball was well-known, and he did little to quash the speculation. “I think that’s a possibility,” Glass said early in his chairmanship regarding the possibility he would buy the team. “I wouldn’t say that would be totally out of the question.”52

With the deadline for Kauffman’s succession plan looming in the not-too-distant future (January 1, 2002), Glass and the other board members formally put the team up for sale in late 1997. In September, Glass had announced he was not going to pursue purchasing the franchise. He had received some stinging criticism over his oversight of the team, particularly the implication that he had been purposely trying to keep the price down, so he could buy it cheaply.53 The process dragged on for nearly a year with no buyer willing to step up to the minimum $75 million asking price.

Only two serious bidders eventually came forward. One, led by Kansas City Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt and Western Resources, a large Topeka-based natural gas and electric utility, offered $27 million at closing and another $25 million at a future date. Moreover, the offer was subject to $70 million in improvements to Royals Stadium being approved within five years, with the buyer controlling the process and timing of the request to governmental bodies. Apparently, some tax implications also prevented them from making a more aggressive bid. A second offer came from a syndicate headed by Miles Prentice, a New York attorney, for close to $75 million. The Royals board suggested that Prentice up his price to $75 million and add some local Kansas Citians to his group, which he did, including Julia Kauffman. In November 1998 the board finally reached an agreement to sell the franchise to Prentice for $75 million. But baseball Commissioner Bud Selig lobbied against Prentice’s group due to concerns that the syndicate was too large and didn’t have deep-enough pockets. Selig’s campaign was enough to sink Prentice’s bid when it finally came up for formal approval a year later.54

Board member McGuff complained, “What I am so frustrated about is that it took so long to get to this point.”55 In response, the board put the franchise back on the market. This time around, they received four bids for the team, including one from Glass himself.

Now 64 years old, Glass had decided to refocus his efforts on purchasing the Royals. Much of the ill-feeling toward his perceived manipulation of the process had evaporated and most observers were frustrated and exasperated with the lack of legitimate buyers. Once it became clear that he was close to buying team outright, he stepped down as the CEO of Wal-Mart. Making it official on January 14, 2000, Glass said he wanted to spend more time with baseball, “a great passion all my life.”56

In March Glass reached an agreement with the board to purchase the franchise for $96 million. Baseball’s owners approved him unanimously. “When we talk about the global issues in baseball his judgment is very well-respected,” Phillies Chairman Bill Giles said. “Of all the small-market people in baseball, he’s probably the most respected. People listen when he speaks.”57 Once approved, Glass said, “I know that Ewing Kauffman wanted me to wind up owning the team. He said that to me more than once.” Adding, “I think [getting back to the postseason] can be done fairly rapidly.”58

On April 18, 2000, David Glass formally became the owner of the Royals. At the time he purchased the team, Glass was obviously an extremely wealthy man but did not show up on the Forbes 400 list of richest Americans or the “near misses,” indicating that Forbes, anyway, believed his net worth was less than the $620 million cutoff. In late 1999 his stock and stock options in Wal-Mart were estimated at a value of $323 million, and of course he had numerous other assets as well, including Glass Enterprises, a real-estate and investment firm.59 To purchase the team, Glass sold 2 million Wal-Mart shares, or around 40 percent of his holdings, valued at roughly $111 million.60

Several months before the purchase, he offered his thoughts on what ownership under a Glass regime would look like. “I am very competitive and despise losing,” Glass said. “I would work very hard to make sure we have a team in Kansas City that is competitive, that is fun to watch. The fun goes out of it when you lose all the time.” That acknowledged, however, Glass was very definitive on his approach to economic issues. “Fiscal responsibility on the part of all owners is one of the prerequisites for baseball to regain some of its competitive balance. I would not be the type of owner who would fund major losses. … The goal of this franchise should be to break even.” This would not bode well for future payroll. In 1999, with one of baseball’s lower payrolls, the Royals recorded a profit for the first time in the 1990s.61

Moreover, Glass was coming from a Wal-Mart culture that valued minimizing expenses among its core values. “Often that meant keeping expenses down. Little counted more to Sam Walton than that,” wrote Wal-Mart researcher Robert Slater. His philosophy was to manage every penny, nickel, and dime; if you did, the dollars would take care of themselves. The more he kept costs low, the more savings he could pass on to his customers.”62

With the purchase, Glass established a board of directors consisting of his wife, Ruth, his two sons, Dan and Donald, his daughter, Dayna Martz, GM Herk Robinson, and Julia Kauffman. In particular, his son Dan was going to have a role in running the team and was shortly named team president.63

In his new role, Dan would be groomed to take a more active role in overseeing the franchise. “He will spend time in all areas, learning the business side as well of the baseball side of the business,” Glass said. “He’s been involved with the baseball organization for about five years –all on the baseball side. It’s always been my thought that this is a family commitment to own the team for the foreseeable future. Some day I’m not going to be around, and I look for him to run it for the family at some point.”64 Now with stable ownership, the new leadership also needed to build out its organization.

Dan had actually spent close to seven years in the organization. He originally joined the Royals in 1993, the year David took over as head of the Royals board, as a baseball operations assistant. Three years later he was named assistant director of player personnel, and his duties gradually expanded to include contract negotiations, involvement in the development of the Latin American program, and arbitration preparation. Dan also made his home in the Kansas City area, removing some of the stigma of his dad’s out-of-town ownership.65

To implement his vision, in June the senior Glass promoted Robinson to chief operating officer, and his assistant Allard Baird to general manager. Baird was clearly in a difficult position: try to build a winning team with a payroll toward the bottom of the sport and a limited budget with which to sign top draft picks. Moreover, despite Glass’s sophistication in improving the systems at Wal-Mart, as one reporter noted, “few teams were more mom-and-pop than the Royals.” According to one report, the Royals did not provide their scouts with company cell phones.67 “I have to approach it a little differently than some teams,” Baird acknowledged, “because we’re always in a development mode.”68 He needed to find quality players less expensively. “We might like a player, but then we can’t afford him. It’s natural to think, ‘Well if you want to compete, you’ve got to step it up.’ What do you step it up to? We know our boundaries, so we’ve got to work harder.”69

One of Baird’s strategies was sign youngsters out of the Dominican Republic. “Our approach is to go younger,” he said. “Sixteen- or seventeen-year olds. High risk, high reward. Rely on development. The failure rate will be higher, no question, but we can work with that.” Adding, “If you don’t have money to spend you project … and as long as your owner understands the risk factor, it’s okay.”70 Specific tactics included a “caravan” approach where Royals scouts traveled throughout the Dominican Republic holding tryout camps so as to scour the countryside, and more radically, looking for talent in South Africa.71

Although the 2002 collective-bargaining agreement increased revenue-sharing, many small-market teams remained reluctant to increase payroll. As sports economist Andrew Zimbalist has pointed out, this was not an illogical response. “The owner will offer a player a salary up to the player’s expected incremental contribution to team revenue,” he wrote. “The fact that the owner receives a revenue-sharing transfer from MLB does not increase the value of a player’s incremental contribution. It does the opposite.”72 And Glass seemed to have taken this lesson to heart, particularly given the team’s struggles on the field in 2001 and 2002. According to one report in September 2002, he alerted his front office that they might be directed to “slash payroll this winter.”73 In the event, the Royals cut payroll by just under $7 million or 14 percent.

By 2001 both the Chiefs and Royals were campaigning to improve their stadiums at the Truman Sports Complex. They were approaching 20 years old and were well behind the new generation of stadiums, particularly in terms of upkeep and available revenue streams. For example, the Royals received $1.5 million in luxury-box revenue while another small-market franchise, the Indians, received $13 million from Jacobs Field.74 Kauffman Stadium was very visionary when it was built,” Dan Glass said. “The infrastructure is there. “We just need to get the amenities up to the standards of Major League Baseball. We’re not asking for a new stadium like the Cardinals.”75

His father, however, was much more circumspect and made it clear the family was distancing itself from having to pay for the improvements, estimated to be around $300 million, $150 million for Arrowhead and $150 million for Kauffman. “My family has $100 million invested in this franchise. I could take that same $100 million and make 10 percent somewhere else,” the senior Glass said. “But I’ve chosen to forgo that amount of money. In a roundabout way, that’s a contribution to baseball in Kansas City. I believe that we are already contributing.”76 He added, “If the team is bad, people don’t really care if you have a state-of-the-art stadium. If you were playing in a cow pasture with wooden bleachers, I would still want to pay for the team — and not the stadium — first and foremost.”77 Under the existing economics he was hitting his target of at least breaking even under the current stadium situation — though the team was not competitive –making something less than $5 million in 2000 and around $1.5 million in operating income in 2001.78

After several years of negotiations, in November 2004 a bi-state bond issue to finance much of the cost of the proposed renovations was voted down overwhelmingly. Two Kansas counties, Wyandotte and Johnson County, and two Missouri counties, Platte and Clay, voted against the proposal. Only voters in Jackson County, Missouri, the county housing the stadiums, came out in favor.79

Two years later, in 2006, after further talks, a new proposal was put on the ballot. In this rendition, the total cost of renovation would be $575 million: $425 million through public borrowing, $75 million from the Chiefs, $25 million from the Royals, and $50 million in state support though income-tax credits. To fund the $425 million, Jackson County voters elected to implement a three-eighths percent sales tax. Before the vote both teams signed a new 25-year lease, contingent on the referendum passing. Had it failed, the county was concerned that existing leases, signed in 1990, could be in jeopardy as they contained a clause requiring that the facilities remained in state-of-the-art condition. As additional incentive to the voters, Major League Baseball promised an All-Star Game to Kansas City between 2010 and 2014 if the vote passed. A second referendum proposed funding $170 million of a $200 million roof to cover Arrowhead that could also be rolled to provide protection for Kauffman, through a use tax on goods purchased by Jackson County businesses outside the state. This second ballot initiative failed, costing Kansas City the 2015 Super Bowl, which it had been promised if both votes passed.80

Construction of the stadium improvements commenced in October 2007, targeting completion in time for the 2008 home opener. During the season, additional construction was programmed for areas not directly affecting the games or the fan experience.81

When Glass formally acquired the franchise, some of the frustration over his trustee-type oversight during the 1990s gave way to cautious optimism that the Royals now had a single, dedicated owner who proclaimed his interest in building a winning franchise. Much of this goodwill dissipated, however, when the team traded two of its star young outfielders, Johnny Damon and Jermaine Dye, in 2001 as their free agency approached. In 2003 the team logged a surprise finish above .500, but it had outplayed its talent level, and in 2004 the Royals regressed. Once again the team traded its best young star and impending free agent, Carlos Beltran, at midseason. In May, in the midst of this disastrous 104-loss season, Herk Robinson retired after 35 years in the Royals organization. The next season the team fell even further, losing a franchise-record 106 games.

The combination of the Royals’ struggles on the field, their low payroll (the team ranked 29th out of 30 teams in 200582), and the lack of a larger financial commitment to the stadium remodel provoked disparagement of Glass and his ownership tenure. Moreover, the franchise value had increased since Glass purchased the team, helped most recently by the increased revenue-sharing codified in the latest collective-bargaining agreement. In 2004 Forbes valued the Royals at $171 million, a 12 percent increase over the previous year (and well in excess of the average increase of 3 percent). Additionally, the Royals showed an operating profit of $6.6 million, again ahead of the league average, which Forbes estimated as a loss of $1.9 million.83 Over the next few years, several observers ranked Glass among the worst owners in sports.84

Glass also had a generous side, often fulfilled behind the scenes, where he would help ex-players or the family of a scout.85 But his competitive drive was being tested against the commitment to firm fiscal restraint and the reality of baseball’s economics.

On the heels of the terrible 2004 and 2005 seasons, the club started horribly in 2006 — after the May 3 game the team was 5-20 — and Glass realized he was going to have to change his approach if he wanted to be competitive. The team won on May 4 to avoid tying the record of 13 straight road losses to open the season, but Glass went public with his discontent, saying “significant changes” were coming. “What’s happening is just unacceptable,” he said. “We’re going to change some things to make it better. I’ve got a bunch of balls in the air right now, and I’m going to catch some of them.” One Associated Press reporter noted that Glass seemed “uncharacteristically agitated.” Most observers felt his statements meant a replacement for GM Allard Baird was forthcoming.86

Unfortunately for Baird, it took longer for Glass to catch the balls than he might have hoped, leaving Baird uncertain as to his ultimate fate, and Glass subject to criticism over the team’s inability to make a move. Finally, on May 31, Atlanta Assistant GM Dayton Moore agreed to become Kansas City’s new GM. Further making the timing particularly bizarre, the amateur draft would be held on June 6. Moore, possessor of the Braves inside scouting information and subject to potential conflicts of interest, could not participate in the Royals draft and would not formally assume his GM duties until June 8. Glass reportedly asked Baird to run the draft even after being fired.87 Both sides quickly realized the awkwardness of this request, and Glass named Assistant GM Muzzy Jackson interim GM for the week and put him in charge of the draft, supported by personnel director Deric Ladnier.

A native of Wichita, Kansas, Moore was given near-complete control over baseball operations, whereas Baird had been subject to a tighter rein.88 This reportedly included a reluctance by ownership to trade veterans and return only prospects. For key trade chips Carlos Beltran and Jermaine Dye, Baird was reportedly required to land major-league-ready talent, a significant handicap as teams looking to bolster their major-league squad often would prefer to surrender prospects rather than weaken their major-league roster. In particular, Baird purportedly had a deal for top prospects worked out for Mike Sweeney, vetoed by Dan.89

Dan Glass, however, minimized his influence on baseball operations. “We try to run this organization the same way the Kauffman family did,” he said. “You hire good baseball people, and then you support them and let them make the decisions. … The only time I get involved is when there may be a lot of money involved, and I think that’s natural. My job is to provide support for the baseball people.” Regarding his disapproving a trade of Joe Randa to the Cubs a few years earlier, where the Royals were purportedly going to receive a prospect while covering much of Randa’s salary with the Cubs, Glass said, “It wasn’t like the trade was a done deal and I stepped in. There was a discussion about a possible deal, and there are always discussions about trades, especially at the winter meetings, and I had some concerns about the direction it was going.”90

The news conference to introduce Moore generated some controversy of its own. Two sports radio reporters, Rhonda Moss and Bob Fescoe, grilled Glass and his son Dan on their handling of the Baird firing. Glass, who clearly wanted the press conference to be about Moore and the future, “grew visibly shaken and chippy in his retorts.” In retribution, Glass revoked the media credentials of the two reporters for the rest of the season.91

On the hiring of Moore, Dan Glass said, “He’s absolutely the best man for this job. And my job is to support him and give him the resources he needs to do his job.”92 The Glass family generally adhered to their hands-off approach and allowed Moore to assemble the club and rebuild the front office as he saw fit. They also loosened their pocketbook somewhat to rebuild the team’s infrastructure, particularly in the scouting and draft spheres.93

During Moore’s first few years he received permission to sign a couple of high-priced free agents to return the team to respectability, landing pitcher Gil Meche after the 2006 season and outfielder Jose Guillen a year later. After a number of years ranked in the bottom five, the Royals bumped their payroll: The 2009 salary list of $76.8 million ranked 21st in baseball, a significant jump over 2006 at $47.7 million, 26th highest.94 The team’s results, however, did not match the increase in salaries. After the 2010 season Moore swapped 2009 Cy Young Award winner and impending free agent Zack Greinke (along with Yuniesky Betancourt) to Milwaukee for four valuable young players: Lorenzo Cain, Alcides Escobar, Jeremy Jeffress and Jake Odorizzi. It would prove to be a great trade, but also highlighted the Royals’ recognition that they were several years away from being competitive and still in a rebuilding mode. Nevertheless, Glass felt that he had the right man in Moore, and in 2009 he extended Moore’s contract through 2014.95

There would be no more high-dollar signings until Moore and Glass felt the team’s young major leaguers and prospects were ready to compete. Finally, after several years of false starts, Kansas City had built up a quality stable of young talent to validate this strategy.96 In the near term, however, Glass pared back payroll to the league’s lowest in 2011 at $35.7 million. For comparison, that season the Yankees’ major-league-high payroll topped $206 million. This retrenching as the team developed its prospects allowed Glass to earn substantial operating income (this is different from net income in that it does not include interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) over the next several years, totaling $73.2 million from 2009 to 2013.97

Kansas City finished 71-91 in 2011, but Moore believed he had assembled a core that could compete in a couple of years. He persuaded Glass to allow him to sign several of his young stars to long-term contacts. The team disappointed in 2012, winning only one more game than in 2011, but once again Moore prevailed and brought in two high-salaried veteran pitchers, James Shields and Ervin Santana, via trades. As a consequence, in 2013 the team’s payroll jumped to 16th at $87.4 million, and the Royals finally broke through, finishing 86-76, clearly a team on the rise.

On the revenue side, Glass’s continued lobbying for additional revenue-sharing proved increasingly successful with each new agreement with the Players Association, and by this time smaller-market teams received significant revenue-sharing proceeds. Now with a chance to win, Glass was willing to boost payroll. The team also benefited from an almost fourfold increase in ticket revenue — up to $80 million — over the decade through 2015.98

The spending increase also came on top of one of baseball’s worst local television deals. After a short experiment with the team-sponsored Royals Sports Television Network, Kansas City had signed a contract in 2008 with the Fox Sports regional network. It runs through 2019 and reportedly currently pays the team $20 million per season. When the team signed the contract, the Royals were coming off a terrible run on the field and a season in which they recorded only a 2.8 rating. Once the Royals started playing well, viewership of the team’s games exploded. In 2015 the regional network reported a rating of 12.3, the highest in baseball, and the highest of any team since the 2002 Mariners. Even during 2017, their second consecutive season without a winning record since their World Series victory, the Royals logged the baseball’s second highest TV rating at 8.5.99 Glass can expect a significant increase in rights fees should these recent ratings continue.100

In 2014 as the team pursued its first postseason appearance in nearly 30 years, Glass reiterated his ownership philosophy: “Small-market teams are always limited. We’ve been willing, when we believed we had an opportunity to, to stretch and go beyond what logically made sense. Our objective, and Dan and I have discussed this before with the Royals, we’ve never viewed the Royals as something where we could make a profit. Our objective has always been to try to break even. I guess you’ll have a year where you might make a little. But you might have years where you lose money. Over a period of time, we’d like to come close to breaking even, at least. And you try to fit it into that framework. But if you have an opportunity to win, you consider doing almost anything.”101

Kansas City finally captured the American League pennant in 2014 and won the franchise’s second World Series the next year. During these and subsequent seasons, Glass continued to support payrolls in the middle of the pack. From 2015 to 2017 the Royals payroll ranged from $120 million to $130 million and ranked as high as 12th in 2015. True to his financially frugal background, upon winning Glass made sure to acknowledge it. “Don’t forget the business side,” he said, “because without them, there’s no baseball side.” He divvied up the credit individually as well: “I say it all the time, but it’s Dan [Glass], and Dayton, and Kevin [Uhlich, senior vice president of business operations] who do all the work.”102 By his actions, though, Glass clearly recognized Moore’s efforts. When Atlanta asked for permission to interview Moore for their GM position after the 2017 season, Glass refused.103

With their new-found success on the field, at the gate, and on television, the Royals looked also to boost revenue from other sources. After the 2016 season the team could not reach an agreement with long-term marketing partner Hy-Vee grocery stores due to their increased price for establishing a marketing relationship.104 The correlation between the recent on-field success and the jump in revenue quantified the extent to which a winning team and organizational credibility can generate significant additional revenues and TV viewership in Kansas City.

As of the spring of 2018, Forbes ranked the Royals as the 27th most valuable franchise in baseball, worth $1.015 billion, and the 2012 CBA defined Kansas City as the 27th largest market. The recent decline in attendance and escalation in payroll from the post-World Series bump led to an operating loss in 2017 of $17 million.105

After many years of finding their way, the Glasses eventually turned around a franchise that had degenerated into baseball’s most hapless: From 1994, the first season after the death of Ewing Kauffman, through 2012, the Royals had the worst winning percentage in baseball. With the 2015 World Series victory behind them, Kansas City was once again at a crossroads in its team building, and the Glasses and Moore were once again facing the challenge of rebuilding in one of baseball’s smallest markets.

Last revised: February 14, 2019

Photo credits

All photos courtesy of the Kansas City Royals except where listed.

Notes

1 Joe McGuff, “Four Kaycee Groups Seek Franchise,” The Sporting News, December 16, 1967: 29.

2 Gene Fox, Sports Guys: Insights, Highlights, and Hoo-hahs from Your Favorite Sports Authorities (Kansas City, Missouri: Addax Publishing, 1999), 82.

3 Jerome Holtzman, “A.L. Vote to Expand Marks 1967 History,” Official Baseball Guide For 1968 (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1968), 180-81; Sid Bordman, “Score Runs High in Selection of Kauffman,” Kansas City Times, January 12, 1968.

4 Bordman, “Score Runs High.”

5 Joe McGuff, “Kauffman Goal: Flag in Five Years; Royals’ Boss Weighs Daring Plan,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1969.

6 Roger D. Launius, Seasons in the Sun: The Story of Big League Baseball in Missouri (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2002), 93.

7 The principal source for Kauffman’s pre-baseball life is Anne Morgan, Prescription for Success: The Life and Values of Ewing Marion Kauffman (Kansas City, Missouri: Andrews and McMeel, 1995); also helpful were Phil Koury in Sid Bordman and Jim Reed, Expansion to Excellence: An Intimate Portrait of the Kansas City Royals (No other publication information presented), iii-viii, and Phil Koury, “Kauffman Puts Winning Record on Line,” Kansas City Star, January 14, 1968.

8 Morgan, 46-7.

9 Dickson Terry, “Kaycee ‘Will Never Lose This Team,’” The Sporting News, January 27, 1968: 23-24.

10 Morgan, 266.

11Mark Mulvoy, “KC is Back with a Vengeance,” Sports Illustrated, May 26, 1969.

12 Frank Deford, “It Ain’t Necessarily So, and Never Was,” Sports Illustrated, March 6, 1972.

13 Joe McGuff, “Kauffman Goal: Flag in Five Years; Royals’ Boss Weighs Daring Plan,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1969, 16.

14 Sam Mellinger, “Forty Years Later, Royals Academy Lives On in Memories,” Kansas City Star, August 2, 2014.

15 Joe McGuff, “Royals Junk Timetable,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1971.

16 Morgan, 176.

17 “Inside Mr. K,” The Squire, March 9, 1989.

18 David Mitchell, “Sports Complex Can’t Afford Upgrades Without Tax Dollars,” Kansas City Business Journal, June 15, 2001.

19 Holtzman, “A.L. Vote to Expand Marks 1967 History,” 180-81; Bordman, “Score Runs High.”

20 Denny Mathews and Fred White with Matt Fulks, Play by Play: 25 Years of Royals Radio (Kansas City, Missouri: Addax Publishing, 1999), 86.

21 Joe McGuff, “’Players Must Learn Facts of Life’ — Kauffman,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1972.

22 Joe McGuff, “ ‘Blame Me for Lemon’s Exit,’ Says Kauffman,” The Sporting News, October 21, 1972: 23; Joe McGuff, “Tallis-Kauffman Split Linked to Lemon Firing,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1974: 15.

23 Sid Bordman, “Royals Promote Burke to G.M. Post,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1974.

24 Morgan, 260.

25 Morgan, 261.

26 Stewart, 149.

27 Whitey Herzog with Kevin Horrigan, White Rat: A Life in Baseball (New York: Harper & Row, 1987), 111.

28 Morgan, 268.

29 Jonathan Rand, “Kauffman Finds Outlet in Baseball,” Kansas City Times, undated clipping.

30 “Lawyer Says Shapiro Held Up Royals Suit in Hopes of Settlement,” Kansas City Times, February 13, 1985; Gene Fox, Sports Guys, 86-88; Mike Fish, “Would-be Buyer of Royals Suing Co-owner Kauffman,” Kansas City Star, February 12, 1985.

31 Bob Nightengale, “A Partnership Is Anchored in K.C.,” The Sporting News, January 25, 1988: 48.

32 Morgan, 294; “Royals Co-owner Bails Out; Highest Bidder Gets Club,” USA Today, August 1, 1990.

33 Charles R.T. Crumpley, “Kauffman OKs Loan to Fogelman,” Kansas City Star, undated clipping.

34 “KC Owner Suggests Canceling Season,” Associated Press, March 11, 1990.

35 Doug Tucker, “IRS Clears Way for K.C. to Purchase the Royals,” USA Today, May 4, 1995; Scott McCartney, “Kansas City Royals Make a Pitch to IRS,” Wall Street Journal, July 15, 1993; Morgan, 310-311; Charles R.T. Crumpley, “Kauffman Went to Great Lengths to Keep Team Here,” Kansas City Star, November 1, 1998.

36 Scott McCartney, “Kansas City Royals Make a Pitch to IRS,” Wall Street Journal, July 15, 1993; Scott McCartney, “Kansas City Royals Score Big Victory with Pitch to IRS,” Wall Street Journal, May 8, 1995; Morgan, 312.

37 Gene Fox, Sports Guys, 90; Morgan, 315-317.

38 Morgan, 315; Fox, 89.

39 Bob Ortega, In Sam We Trust: The Untold Story of Sam Walton and How Wal-Mart Is Devouring the World (London: Kogan Page, 1999), 95.

40 Ortega, 95-99.

41 Robert Slater, The Wal-Mart Triumph (New York: Portfolio, 2004), 30; Ortega, 56-57.

42 “David Glass Builds on Wal-Mart Legacy,” USA Today, July 27, 1995.

43 “Wal-Mart CEO Glass Leaves After 12 Years,” Oneonta Star, January 15, 2000.

44 “Walton in Group Wanting to Buy Houston Astros,” Oklahoma Journal Record, August 3, 1991; “Houston Astros sold for $680 million,” May 16, 2011, cbsnews.com/news/houston-astros-sold-for-680-million; Constance L. Hays, “Wal-Mart Agrees to Sell Food Supplier,” May 3, 2003, https://nytimes.com/2003/05/03/business/wal-mart-agrees-to-sell-food-supplier.html.

45 “David Glass Builds on Wal-Mart Legacy,” USA Today, July 27, 1995.

46 “Keeping Royals All in the Family,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, May 24-30, 2000.

47 John Helyar, “And We Thought They Sold Beer at Games to Wash Down Peanuts,” Wall Street Journal, January 31, 1994.

48 Joe Posnanski, “The Royals Decade,” January 1, 2010, https://joeposnanski.com/joevault/?p=50.

49 Fox, 90.

50 Fox, 90; Brandon Copple, “Home Stretch,” Forbes, June 12, 2000.

51 Julia was the biological daughter of Muriel and adopted by Ewing after they were married.

52 Fox, 90; Steven Rock, “Kauffman’s Daughter Happy That Glass Will Own Team,” Kansas City Star, April 17, 2000.

53 Fox, 90; Jerry Heaster, “Search for Dream Owner of Royals Striking Out,” Oklahoma City Journal Record, August 4, 1998; Jeffrey Flanagan, “Glass’ Thankless Task Almost Complete,” Kansas City Star, August 13, 1998.

54 Ronald Blum, “Royals Owners Approve Royals Sale,” Sun Sentinel, April 18, 2000; Brandon Copple, “Home Stretch”; “Baseball Rejects Prentice Bid for Royals,” November 11, 1999, https://a.espncdn.com/mlb/news/1999/1111/165380.html.

55 “Baseball Rejects Prentice Bid for Royals.”

56 “Wal-Mart CEO Glass Leaves After 12 Years,” Oneonta Star, January 15, 2000.

57 Steven Rock, “Potential Owner of Royals Has Business Savvy, Passion for Baseball and a Lot of Money,” Kansas City Star, November 27, 1999

58 “Owners Approve Sale of Royals,” April 17, 2000. cbsnews.com/news/owners-approve-sale-of-royals.

59 Rock, “Potential Owner of Royals.”

60 Steven Rock, “Glass Plans to Sell Stock to Pay for Team,” Kansas City Star, March 22, 2000.

61 Rock, “Potential Owner of Royals.”

62 Slater, 53.

63 “Family on Board,” New York Times, May 5, 2003; Ronald Blum, “Royals Owners Approve Royals Sale,” Sun Sentinel, April 18, 2000.

64 “Keeping Royals All in the Family,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, May 24-30, 2000.

65 mlb.com/royals/team/front-office/dan-glass; Jeffrey Flanagan, “Dan Glass ‘Proud’ to See Royals Back on Top,” November 13, 2015, https://mlb.com/news/royals-president-dan-glass-proud-of-team/c-157236190.

66 Sam Walker, “On Sports: The Front Office Blues,” Wall Street Journal, August 9, 2002.

67 Harvey Araton, “Restoration Project,” New York Times, July 9, 2012.

68 Mark Kind, “Profile: Allard Baird, ‘He’ll Tell You the Hard Things,’” Kansas City Business Journal, January 6, 2003.

69 Alan M. Klein, Growing the Game: The Globalization of Major League Baseball (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 38.

70 Klein, 40-41.

71 Klein, 43-44.

72 Andrew Zimbalist, May the Best Team Win: Baseball Economics and Public Policy (Washington: Brookings Institution, 2003), 103-104.

73 Zimbalist, 108-109, quoting Bob Nightengale, USA Today Sports Weekly, September 4-10, 2002.

74 Copple, “Home Stretch.”

75 David Mitchell, “Sports Complex Can’t Afford Upgrades Without Tax Dollars,” Kansas City Business Journal, June 15, 2001.

76 Steven Rock, “Glass Says He Won’t Put His Own Money Into a Stadium,” Kansas City Star, July 7, 2001.

77 Ibid.

78 Ibid.; Sam Walker, “On Sports: The Front Office Blues,” Wall Street Journal, August 9, 2002.

79 Clark Corbin, “Voters Nix Bistate Nlans,” November 4, 2004, https://bonnersprings.com/news/2004/nov/04/voters_nix_bistate/.

80 Yvette Shields, “Vote Due on K.C. Stadiums; County Legislators, Public Will Weigh In,” The Bond Buyer, March 22, 2006; “Voters OK Stadium Upgrades, Reject Rolling Roof,” Kansas City Business Journal, April 5, 2006; Joel Thorman, “Super Bowl 2015 Was Supposed to Be in Kansas City,” January 30, 2015, https://arrowheadpride.com/2015/1/30/7950913/super-bowl-2015-was-supposed-to-be-in-kansas-city.

81 “Royals Hold Ground Breaking Ceremony for Stadium Renovation,” October 3, 2007, https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/baseball2007-10-03-883213026_x.htm.

82 baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/2005-misc.shtml. For consistency, I use the payroll figures published at baseball-reference.com throughout this essay unless otherwise noted. They can differ from other published sources and “may not include every bonus a team paid in a season, or players called up or acquired mid-season.”

83 “MLB Valuations,” April 26, 2004, https://forbes.com/forbes/2004/0426/066tab.html#364c859d4a70.

84 Dave Zirin devotes a chapter to Glass in his book Bad Sports: How Owners Are Ruining the Games We Love; Rolling Stone put Glass at number 10 in their ranking of the worst owners in sports; ESPN’s page 2 staff ranked him number six in their list of the greediest owners in sports; and Bleacher Report listed him at number eight among the worst owners of all time. Dave Zirin, Bad Sports: How Owners Are Ruining the Games We Love (New York: The New Press, 2012), 133-140; Jeb Lund, The Worst Owners in Sports, Rolling Stone, November 25, 2014, rollingstone.com/culture/lists/the-15-worst-owners-in-sports-20141125/david-glass-kansas-city-royals-20141125; “Greediest Owners in Sports,” undated, https://espn.com/page2/s/list/owners/greediest.html; Ezri Silver, “The 20 Worst Owners in Sports History,” June 26, 2010, https://bleacherreport.com/articles/411966-the-20-worst-owners-in-sports-history#slide13.

85 Jason Whitlock, “Glass Kind, but Still the Worst Owner,” Kansas City Star, June 25, 2006.

86 Doug Tucker, “Royals Owner Vows to Make Changes,” Lincoln Journal Star, May 6, 2006; “Royals Fire GM Baird; Moore Hired,” ESPN, May 31, 2006, https://espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=2464544.

87 Peter Gammons, “Glass Abused Baird,” ESPN, June 2, 2006.

88 Despite some suggestions that Moore negotiated for complete control, Moore denied he ever demanded it. Dayton Moore and Matt Fulks, More Than a Season: Building a Championship Culture (Chicago: Triumph, 2015), 57.

89 Wally Fish, “Defending Allard Baird, Plus Other News,” December 20, 2009, https://kingsofkauffman.com/2009/12/20/defending-allard-baird-plus-other-news; Joe Posnanski, “The Royals Decade,” January 1, 2010, https://joeposnanski.com/joevault/?p=50.

90 “Dan Glass: Family Tries to Emulate Kauffman,” Kansas City Star, undated clipping.

91 Jason Whitlock, “This Glass Is Empty,” ESPN Page 2, June 6, 2006, https://proxy.espn.com/espn/page2/story?page=whitlock/060615.

92 “Dan Glass: Family Tries to Emulate Kauffman,” Kansas City Star, undated clipping.

93 Vahe Gregorian, “David Glass Reflects on Royals’ Rise and ‘Taking the Heat,’” Kansas City Star, October 16, 2014.

94 baseball-reference.com.

95 Tracy Ringolsby,” Glass Deserves Credit for Royals’ Success,” November 7, 2015, https://mlb.com/news/david-glass-plays-big-role-in-royals-success/c-156725516.

96 Along with the players picked up in the Greinke trade, the organization boasted first baseman Billy Butler, first baseman Eric Hosmer, third baseman Mike Moustakas, catcher Salvador Perez, outfielder Alex Gordon, outfielder Wil Myers, and pitchers Danny Duffy, Yordano Ventura, and Kelvin Herrera.

97 Information from Forbes in Sam Mellinger, “Royals’ ‘Break-Even’ Claim Is Plausible, but Front Office Can Still Do More,” February 14, 2014, https://kansascity.com/sports/mlb/kansas-city-royals/article339151.html.

98 Sam Mellinger, “The Small Market Changes That Helped the Small Market Royals Spend Big,” February 1, 2016, https://kansascity.com/sports/spt-columns-blogs/sam-mellinger/article57527133.html.

99 Maury Brown, “Here Are the 2017 MLB Prime Time Television Ratings for Each Team,” October 10, 2017, https://forbes.com/sites/maurybrown/2017/10/10/here-are-the-2017-mlb-prime-time-television-ratings-for-each-team/2/#e94204463ccd.

100 Max Rieper, “How Much Should the Royals Expect from Their Next Television Deal?” December 15, 2015, royalsreview.com/2015/12/15/9888970/how-much-should-the-royals-expect-from-their-next-television-deal; Blair Kerkhoff, “Royals Set TV Rating Record on Fox Sports KC,” October 5, 2015, https://kansascity.com/sports/mlb/kansas-city-royals/article37795596.html.