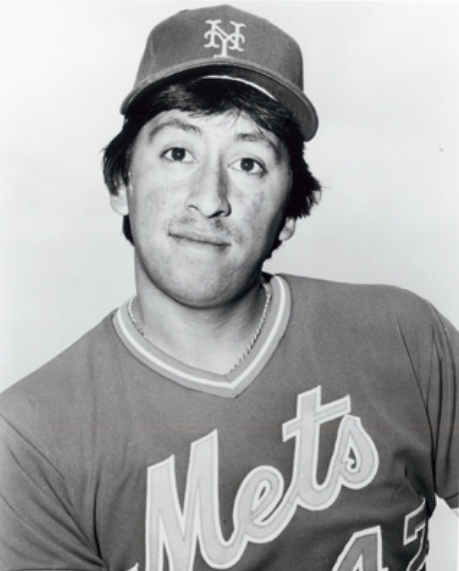

Jesse Orosco

Jesse Orosco appeared in 1,252 regular-season games during his career, the most of any major-league pitcher. As of Opening Day 2015, the active hurler with the most appearances was LaTroy Hawkins with an even 1,000, so Orosco’s record endured for at least some time. The lefty spent most of his 24 seasons in the majors as a specialist. From 1988 until 2003 (when he was 46), Orosco averaged 0.8 innings per game.

His finest moments, however, came during his years as a closer with the New York Mets in the 1980s. When the Mets won the National League pennant in 1986, Orosco won three games in the Championship Series against Houston. He leapt for joy after finishing the grueling 16-inning Game Six that clinched the series. He was also on the mound when Game Seven of the World Series against Boston ended, once again hurling his glove skyward. “If you ever get a chance to throw the last pitch, that’s a dream come true,” said Orosco in 1987.1

Jesse Russell Orosco was born on April 21, 1957, in Santa Barbara, California. His father, Raymond Orosco, was a native of Austin, Texas. Ray’s parents, who were of Mexican origin, moved their family from Texas to Michigan before settling in the town of Goleta, right next to Santa Barbara, in the 1940s.2 Ray worked in construction, including at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He had a chance to play professional baseball but chose family life instead.3

Ray’s wife, Tomasa Mata, was born in Mexico and came to California when she was young. Jesse was the fifth of her seven children.4 He had an older brother named Raymond Jr. and five sisters.5

Tomasa Orosco tried for a while to make a right-hander out of little Jesse when he was first sitting up to eat. “We would give him his plate,” she said, “and he would reach for the spoon with his left hand. I took it away and put it in his right hand. But he immediately switched back to the left hand. Finally we just let him go. We realized we had a left-hander.”6

The southpaw showed talent at a young age. “Ever since I was a little tot, my plan was to play in the majors,” he said in 1999.7 Previously, his mother had said, “Jesse started at 6 years old on a baseball team with the Boys’ Club in Santa Barbara. He was supposed to be 7 years old. But my husband and the manager of the Boys’ Club got him in. He was a good pitcher then.”8

As Sports Illustrated wrote in 1983, “Raymond Orosco Sr. had a powerful influence on his son’s life. He had founded and funded, pitched and played first base for a semipro team called the Santa Barbara Jets. ‘He bought the bats and balls and uniforms,’ says Tomasa, who kept score at the Jets’ games. ‘I sewed on all the words.’ Jesse and Raymond Jr. were batboys, while the five Orosco daughters sold sno-cones and tickets to raise money for the churches and charities the team supported.”9

Ray Orosco also managed the Jets. In addition, he sponsored and played for a team called the Goleta Merchants. Furthermore, he maintained Laguna Park Stadium in Santa Barbara.10 When Jesse was a boy, the Santa Barbara Rancheros (a Mets farm club) played there from 1961 through 1963; then the Santa Barbara Dodgers were there from 1964 through 1967.11

Orosco, who grew to a height of 6-feet-2, went to Santa Barbara High School and went on to Santa Barbara City College. In 2000 the city’s Athletic Round Table made him a member of its Hall of Fame.

In 1977 the St. Louis Cardinals made Orosco their seventh-round pick in the January phase of the amateur draft. He did not sign, but he did the following January, when the Minnesota Twins took him in the second round. Orosco played rookie ball in the Appalachian League in 1978. He was impressive in 20 relief outings, posting a 1.12 ERA and striking out 48 batters in 40 innings. He then put up a 0.26 ERA in the Instructional League and earned the label of top southpaw prospect in Minnesota’s farm system.12

Orosco became a Met in February 1979. He was the player to be named later in the deal that sent Jerry Koosman, one of the heroes of the Mets’ 1969 World Series champions and 1973 NL pennant winners, to the Twins. Despite his lack of experience, Orosco went to spring training with the big club as a nonroster invitee. Mets beat writer Jack Lang said, “He is a couple of years away.”13

Nonetheless, Orosco made it all the way to New York. It did not hurt that two veteran lefties, Kevin Kobel and Bob Myrick, were on the disabled list — but later that summer, Jack Lang wrote that the franchise’s parsimony at the time was also a factor. “[General manager Joe] McDonald and the people at the Mets who count pennies shoved Neil Allen, Mike Scott and Jesse Orosco down [Joe] Torre’s throat. … They just weren’t ready this year.”14 Torre, who was then the Mets’ manager, allegedly vowed that he would never again rush a young pitcher the same way.15

The rookie pitched well in limited opportunities during April and early May, but he then hit a rocky patch. The Mets gave Orosco two starts in June but sent him down to Triple-A Tidewater after obtaining veteran lefty Andy Hassler. Orosco started in 15 out of his 16 appearances for the Tides. He stepped down to Double-A for all of 1980, but was back in the bullpen, starting just once in 37 outings. Returning to Tidewater in 1981, he was a part-time starter (10 starts in 47 appearances). New York recalled Orosco in September 1981, and he did not appear again in the minors until 2000, when he served an injury-rehab assignment.

During this period, Orosco also gained experience in winter ball. For three seasons (1980-81 through 1982-83), he played in Venezuela for Tiburones de La Guaira. In 69 total games, he was 6-6 with a 1.92 ERA and five saves. He also pitched in the playoffs each year; the Sharks became league champions in 1982-83.

In 1982 the Mets focused Orosco on the bullpen for good — his two starts that summer were his last in the majors. George Vecsey of the New York Times quoted Bill Monbouquette, who was New York’s pitching coach in 1982: “He’d go four innings and his ball would drop into the 70s. We thought Jesse should be a relief pitcher, and we could see Jesse was pitching defensively. It wasn’t exactly fear of the bat, but he was nibbling. You’re not going to get the calls from the umpire that way and you’re not going to finish off the batter that way.” Monbouquette added, “We dug into him. It wasn’t exactly an ultimatum, but we told him he could be a good relief pitcher if he learned to attack the hitters.”16

The key part of “we” was George Bamberger, a former pitcher and pitching coach, who managed the Mets from 1982 until June 1983. As Vecsey wrote that month, “Orosco believes Bamberger turned him around, kept him in the majors, taught him a slider, taught him tenacity.” Technical teaching from “Bambi,” including a higher arm angle on the slider, was certainly important — but the confidence he instilled was something for which Orosco was even more thankful.17

On August 16, 1982, Raymond Orosco Sr. died of a heart attack on his construction job.18 He was just 55. Tomasa recalled, “At the funeral Jesse told me, ‘Mom, Dad got me this far, and I’m going to work harder for him and you.’ But I didn’t know he was going to work this hard.”19 The southpaw continued to develop with the Mets that summer. His won-lost record was 4-10, but he posted a 2.72 ERA in 54 games, striking out 89 men in 109⅓ innings.

Orosco viewed the game of September 10, 1982, as a key juncture in his career. At St. Louis, with two outs in the seventh inning, he relieved Craig Swan with runners on first and second and the Mets leading 1-0. He got the third out, and the Mets added an insurance run. In the ninth inning, Keith Hernandez — who came to New York the following summer — hit a home run. Two outs later, Gene Tenace walked. “Any other manager might have taken me out,” Orosco said. But Bamberger told him that it was his game to save, and Jesse retired Ozzie Smith to finish it.20

Other teams again wanted Orosco in trade, but the Mets did not want to deal him. It was a wise choice. Orosco’s work paid off even more handsomely in 1983, when he had his best overall season and perhaps the best of any reliever in Mets history. “Strikes, confidence, concentration — I’ve got it all right now,” he said that May. “I’m sky-high!”21 He pitched a career-high 110 innings in 62 games, posting a remarkable 1.47 ERA. His 13 wins — which included both ends of a doubleheader on July 31 — were also a single-season best, and he lost just seven while posting 17 saves. Orosco was named to the NL All-Star team and struck out the only batter he faced, Ben Oglivie. He finished third in the voting for the NL Cy Young Award.

Orosco was an NL All-Star again in 1984, though he did not get into the game. His 31 saves were by far his best one-season total, and he was 10-6 with a 2.59 ERA.

In December 1984, Orosco married Leticia Banda, a native of East Los Angeles. He met her one day while he was in the bullpen at Dodger Stadium. “It was the first game I ever went to,” Leticia remembered in 1988. “My girlfriend dragged me there. I was just a spectator and we met by chance.”22 The Oroscos had three children: Jesse Jr., Natalie, and Alyssa. Jesse Jr. became a 38th-round draft pick of the Arizona Diamondbacks in 2008. He pitched in the low minors in 2008 and 2009, and continued in independent leagues as late as 2011.

Orosco’s save total dipped to 17 in 1985. Early that year, he had some elbow problems and struggled before righting himself (he finished the season at 8-6, 2.73). That August, manager Davey Johnson said, “I might have babied him a little too much earlier. He had a time, earlier on in the season, when he was successful only about half the time on his save situations. He wasn’t winning the matchups he would normally win.”23

That remark showed how bullpen management was continuing to evolve in the 1980s. At that point, bullpens were smaller and not as specialized as they became over time. The distinction between setup men, situational relievers, and the closer had not yet developed fully. Doug Sisk, a righty, got 11 saves in 1983 and 15 in 1984. Then in 1985, rookie Roger McDowell, also a righty, emerged. McDowell equaled Orosco’s 17 saves. In his book about the 1985 season, Bats, Davey Johnson referred to how McDowell replaced Sisk as his number one right-handed short man. It was not uncommon then to see co-closers.

At that time, top relievers were also still often deployed as “firemen” rather than coming in with bases empty at the start of the ninth. Against Philadelphia at Shea Stadium on August 13, the Mets were up 4-1 in the eighth inning, but the Phillies loaded the bases with three singles off Rick Aguilera. Orosco came in with nobody out. He retired Ozzie Virgil on a harmless sacrifice fly, got Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt to pop out, and struck out Von Hayes. A scoreless ninth inning followed.

Orosco was unflappable on the mound. Looking back in 2014, he said, “I had nerves a lot of the time, but I embraced the pressure and loved it.”24 The calm that Orosco projected influenced perceptions. Davey Johnson later said, “I don’t think he looks at every situation as life and death, and that’s what a reliever has to do.”25

The McDowell-Orosco tandem remained very effective in 1986. McDowell had 22 saves and Orosco had 21 — marking the third of six times as of 2015 that a big-league team has had two pitchers with 20 or more saves in a season.26

A unique instance of how Johnson juggled the two — and an indication of Orosco’s athleticism — came on July 22 in an extra-inning game at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium. Orosco was on the mound in the 10th inning when Eric Davis of the Reds slid hard into Ray Knight while stealing third base. A fight broke out between them and it erupted into a 15-minute bench-clearing brawl. Knight and Kevin Mitchell were ejected, so Gary Carter had to fill in at third base. Darryl Strawberry had previously been ejected too. Thus, one out later, Orosco went to right field and McDowell relieved him. With two out in the 11th, Orosco returned to the hill to face lefty Max Venable, prompting a protest from Reds manager Pete Rose, who contended that Orosco should not have been allowed to warm up. Jesse finished out that inning and threw a scoreless 12th. He then went back to right field for the 13th inning — cleanly handling a liner from Tony Pérez — and the 14th, when McDowell (who had earlier played both right and left field) got three outs to end the game.

“I hoped the game would last 20 innings,” Orosco said. “We were having a lot of fun.”27 Though born of necessity, Johnson’s maneuvering would have made Paul Richards proud.28 Orosco never got another chance to play a different position, but he often helped himself with his fielding on the mound — his reflexes were excellent.

Only twice during the 1986 regular season did Orosco pitch as many as three innings in a game. His third three-inning effort that year came in Game Six of the NL Championship Series against Houston, the 16-inning battle royal. Ideally, it would have been a straightforward one-inning save, but Billy Hatcher’s home run extended the game. “Orosco watched the ball sail into the left-field foul pole, fighting his anger. ‘I told myself, ‘It’s not over. Not yet.’”29

By the time that outing was done, Orosco was running on fumes, having faced 14 batters and thrown 54 pitches. When the last batter, Kevin Bass, came to the plate, Doug Sisk (a.k.a. “Doug Risk”) was warming up. The only other available option was Randy Niemann, who didn’t appear at all that postseason. As coach Bud Harrelson wrote, “This was going to be Orosco’s game, win or lose.”30

“I was tired,” Orosco confirmed when interviewed for an episode of the MLB Network show MLB’s 20 Greatest Games. “I was just trying to make those pitches. In that time of the moment, you just have to reach back and get everything you have inside you and go for it.”31 Of course, the situation imposed mental as well as physical demands. “Was Orosco nervous? Could any human not be? ‘Sure I was,’ he said. ‘But I told myself, ‘You have the ball. You have the power. Don’t let these guys down.”32

Orosco was the first reliever to win three games in a postseason series, and he remains the only one to do so. He had no decisions in the 1986 World Series, but he did get two saves. In Game Seven he entered with the tying run on second and nobody out in the eighth inning. He later admitted to being nervous again. “I wasn’t thinking about baseball. I was looking for the bathroom. … I just told myself, ‘Stay within yourself, this is no time to fold.’”33 The image of him after recording the last out — on his knees with arms and face thrust to the heavens — is one of the most memorable in Mets history.

Less well remembered, though, is how Orosco drove in the final run of the Series. In a rare plate appearance — just his eighth of the year — he came up with runners on first and second. On NBC-TV, Joe Garagiola said, “I’d almost bet the house that he’s gonna bunt.” Orosco did show bunt on the first pitch, a ball. He had squared on the second pitch too — but drew back his bat and chopped a single, prompting Vin Scully to say, “Joe, you just lost your house!”34

“We didn’t have anything going on in the early ’80s, took our licks the first few years,” Orosco said upon his retirement. “That was great, that was very memorable, to go from the worst to the best.” Only Mookie Wilson and Wally Backman had longer consecutive service in the Mets organization, and they both first reached the majors in 1980.35

Whether Orosco’s glove ever came down after he threw it up to celebrate the end of the Series was the subject of jokes. What really happened, though, was that he donated it as part of a drive to support New York City policeman Steven McDonald, an avid Mets fan who’d been paralyzed by a gunshot while on duty.36 Orosco also became known for buying and donating hundreds of tickets so that children from broken homes could enjoy a day at a big-league ballpark.37

The 1987 season was not a happy one for Orosco. He had 16 saves (the last time he reached double digits in this category) but was 3-9 with a 4.44 ERA. His performance brought him into disfavor with Davey Johnson — his agent, Alan Meersand, described it as “a real cold war” — and with the New York fans, who went so far as to subject him to death threats.38 Orosco asked for a trade, and that December he went to the Los Angeles Dodgers as part of a three-way deal that also involved the Oakland A’s.

On March 3, 1988, during spring training, an Orosco prank became memorable. He daubed eye black inside the cap of another new Dodger, ultra-intense outfielder Kirk Gibson, who wiped his forehead and smudged the stuff all over his arm. As their teammates laughed, Gibson left angrily. But when he returned to camp the next day, he said, “I’m the best teammate you’ll ever have, you just don’t realize it yet.” As Gibson further recalled in 2010, “From that point on, we went out there and got after it. We were world champions and nobody picked us to do so.”39

On the way to winning the other World Series ring of his career, Orosco was 3-2, 2.72 in 55 games. He picked up nine saves, third on the team behind Jay Howell and Alejandro Peña. Howell, who had come to Los Angeles in the same three-way deal, was originally viewed as Orosco’s righty co-closer. 40 As it developed, though, Dodgers manager Tom Lasorda reduced Jesse’s role. In the playoffs, Orosco faced his old team, the Mets. He allowed two earned runs in 2⅓ innings across four games, getting no decisions. He did not appear in the five-game upset of the Oakland A’s.

After the 1988 season, the Dodgers let Orosco — “widely perceived to be over the hill,” according to Peter Gammons in Sports Illustrated — walk into free agency.41 He signed with the Cleveland Indians and spent three seasons there. He was most effective in 1989, striking out 79 men in 78 innings with a 2.08 ERA. His second year with the Tribe, 1990, was the last time in his career that his innings pitched total exceeded his number of appearances. However, “everything seemed to hit the wall for me in my second year in Cleveland,” Orosco recalled in 1994. “One day I almost quit and didn’t go to the park. My wife talked me into hanging with it.”42

As the Toledo Blade wrote in 1996, those were “lean times for the franchise. Eventually, the veteran reliever got his wish and was traded to Milwaukee after the 1991 season.”43 To illustrate Orosco’s discontent, after the deal Alan Meersand quipped, “Terry Anderson [the American journalist who’d been held captive in Lebanon for nearly seven years] wasn’t the last hostage freed — it was Jesse Orosco, from the bondage of the Cleveland Indians.”44

Orosco spent three seasons with the Brewers too. He loved it in Milwaukee — how he was treated and how manager Phil Garner told him what his role would be. “I felt like part of the team again,” he said. He revived his career in 1992 as a setup man and re-emerged as a closer in the second half of 1993, getting eight saves after Doug Henry lost the job.45

General manager Sal Bando viewed Orosco as an interim solution, though, saying, “It’s unrealistic to ask Jesse to be that guy all year.”46 Thus the veteran was back in his situational role in 1994. It was a down year for him — his ERA was 5.08 in 40 appearances, and he blew all four of his save chances. Even in August, a few days after the historic players’ strike had begun, the Milwaukee press wrote that he was not expected back.47 He became a free agent that October.

Five years with the Baltimore Orioles then followed. Orosco signed in April 1995, not long after the crippling strike had ended. He led the American League with 65 appearances that year, a figure that is quite low by today’s standards.48 Two years later, he reached a personal single-season high with 71. The Orioles reached the postseason in both 1996 and 1997, managed by Davey Johnson. In both years Orosco pitched in the AL Division Series and AL Championship Series.

By that time, the tension between Johnson and Orosco was a thing of the past. When Baltimore hired Johnson, Orosco noted how the skipper was central to the Mets’ turnaround in the mid-1980s.49 During the 1996 playoffs, both men expressed their faith in each other.50

Approaching his 40s, rigorous offseason conditioning and his knowledge of hitters kept Orosco in the game. Ray Miller, Baltimore’s pitching coach in 1997, said, “He’s got a great body and excellent agility.” Miller added, “He’s very relaxed under pressure and very confident. No matter how old a guy is, that’s what you want to see out there.”51

On August 17, 1999, Orosco broke the record for games pitched in the major leagues, then held by Dennis Eckersley. Appearance number 1,072 came at Baltimore’s Camden Yards. In the stands was Tomasa Orosco, along with Leticia, Natalie, and Alyssa. Twelve-year-old Jesse Jr. served as batboy and sat beside Ray Miller, who had become manager. Orosco retired lefty swinger Todd Walker on two pitches and his work was done for the night. Jesse Jr. ran out to greet his father, who noted the anniversary of Ray Orosco Sr.’s death the previous day.52

In December 1999 the Orioles traded Orosco to the Mets for Chuck McElroy. The veteran waived his 10-and-5 rights, in part because Baltimore’s new manager was Mike Hargrove, and they had not seen eye to eye in Cleveland. Orosco never got a chance to pitch for New York again — although he was excited about the opportunity — because the Mets sent him on to the St. Louis Cardinals for Joe McEwing the following March.53 He got into just six games that year for St. Louis, three in April and three in June. A sore elbow landed him on the disabled list twice; the torn flexor muscle wound up requiring surgery. It was the only serious injury of his career.

In the spring of 2001, Orosco returned to Los Angeles. Teammate Mike Fetters, whom Orosco had mentored with the Brewers, said, “As soon as I heard his arm was fine, I knew he was going to make this team because nothing about Jesse has changed from his first day in the big leagues until now, he’s just more polished.”54

As it turned out, the Dodgers released Orosco at the end of March 2001 — but in late April, they re-signed him to a minor-league contract. He pitched in 10 games for Triple-A Las Vegas and was back with LA by late May. He appeared 35 times for the Dodgers over the remainder of 2001 and 56 more in 2002, after he signed another one-year deal. That April, he said, “They’re joking about me still being in the big leagues, and I’m glad I’m still around so they can joke about it. I’ve probably heard them all by now. … It doesn’t bother me at all because it’s all in good fun.”55

Orosco and the Dodgers parted ways after the 2002 season. That November he signed with the San Diego Padres, an attractive team because they were close to his home. In spring training 2003, Jeff Pearlman — author of the ’86 Mets chronicle The Bad Guys Won — described for Sports Illustrated how Orosco had adapted as a pitcher over the years. “When his velocity dropped off, he depended more on his slider, and when his slider began to flatten, he picked up a split-finger changeup that has become his out pitch.”56 A little later that season, another article noted Orosco’s “wicked changeup” while also observing that he used a cutter more often and knew how to spot his “still decent” fastball. “You always need to make adjustments in this game,” he said.57

Orosco got into 42 games as a Padre in 2003, recording the last two of his 144 major-league saves. That July the New York Yankees obtained the 46-year-old. Jesse was reunited with his first big-league skipper, Joe Torre, and his pitching coach with the Mets in the mid-1980s, Mel Stottlemyre. “He continues to pitch and he continues to have a passion for it,” said Torre.58

Orosco pitched 4⅓ innings in 15 games for the Yankees before they traded him to his original organization, Minnesota. He made his last eight appearances in the majors with the Twins that September. They included his last of 87 big-league wins (against 80 losses) on September 24.

In November 2003, Orosco signed a minor-league deal with the Arizona Diamondbacks. That winter, though, he found that he’d lost the excitement to get going. He told Leticia, “I just don’t think I have it in me to get prepared this year.” In January 2004 he retired.59

For most of the following decade, Orosco enjoyed a life of leisure, watching his children grow up and playing lots of golf. In 2011, however, he wanted to get back in baseball. He didn’t seek a coaching job in the minors or indie ball, so he took a position with the San Diego branch of the Frozen Ropes baseball and softball training centers, close to his home in Carmel Valley.60 Daughter Natalie later joined the clinic as a softball instructor. As of 2015, though Jesse was no longer with Frozen Ropes, he remained active in teaching kids how to pitch.61

Jesse Orosco frequently said that he would have been happy playing just several years in the majors. He didn’t make it to age 50, as was often speculated, or to 47, his longstanding uniform number. But only five men have pitched in more seasons as a major leaguer.62 His arm was a great natural gift, but he worked very hard to stay in shape. Affordability was also a factor; the most Orosco ever made in one season was $1.215 million. A strong mental approach — with a boost from his supportive family — helped a lot too.

The bottom line, though, was effectiveness. During his career, batters hit just .223 against Orosco, with an on-base percentage of .309, a slugging percentage of .335 — and not that marked a difference between lefties and righties.63 He summed it up nicely in 1999: “What I’m most happy about is the fact that I’ve been able to be out there every day. The manager knows I’ll be there. There have been some ups and downs but I’ve been pretty consistent over the course of more than 1,000 games.”64

Sources other than those cited in Notes:

purapelota.com (Venezuelan statistics).

frozenropes.com.

ancestry.com.

Notes

1 George Vecsey, “Sports of the Times: Jesse Orosco and the Law of Gravity,” New York Times, February 23, 1987.

2 Obituary of Jesse Orosco’s aunt, Simona Orosco Manriquez, Santa Barbara News-Press, November 19, 2014.

3 Richard A. Santillán, Mexican American Baseball in the Central Coast (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Press, 2013), 66.

4 Gordon S. White Jr., “Orosco, a Golden Arm in Met Bullpen,” New York Times, August 10, 1983.

5 E.M. Swift, “Oh, what a relief he is,” Sports Illustrated, September 5, 1983.

6 White, “Orosco, a Golden Arm in Met Bullpen.”

7 David Ginsburg, “Baltimore’s Orosco just keeps throwing strikes,” Associated Press, June 29, 1999.

8 White, “Orosco, A Golden Arm in Met Bullpen.”

9 White, “Orosco, A Golden Arm in Met Bullpen.”

10 Santillán, Mexican American Baseball in the Central Coast, 66.

11 Barney Brantingham, “The Short, Happy Life of Laguna Ball Park,” Santa Barbara Independent, May 5, 2011.

12 Jack Lang, “Mets’ Farm Crop Fails to Yield Bat Prospects,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1979: 36. Bob Fowler, “Fast-Dealing Twins’ Target: Ivie,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1979: 43.

13 Lang, “Mets’ Farm Crop Fails to Yield Bat Prospects.”

14 Jack Lang, “Mets Get Two Vets to Replace Kid Hurlers,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1979: 27.

15 Swift, “Oh, what a relief he is.”

16 George Vecsey, “Orosco Says Thank You,” New York Times, June 15, 1983.

17 Vecsey, “Orosco Says Thank You.”

18 Vecsey, “Orosco Says Thank You.”

19 Swift, “Oh, what a relief he is.”

20 Vecsey, “Orosco Says Thank You.” Jack Lang, “All-Star Orosco Credits Bamberger,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1983: 15.

21 Bruce Lowitt, “Mets rally past Cincy,” Associated Press, May 9, 1983.

22 Dick Young, “Vegas bookie picks Washington,” New York Post, January 4, 1985. Sam McManis, “They Wanted Out to Escape Doubts,” Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1988.

23 “Mets trip Phils for 9th in row,” Associated Press, August 14, 1985.

24 Facebook Q&A with Jesse Orosco, organized by the New York Mets, August 15, 2014.

25 Josh Robbins, “Orosco Still Has Something Left,” Orlando Sentinel, May 13, 2002.

26 The other pairs: Eddie Fisher and Hoyt Wilhelm (1965 Chicago White Sox); Greg Minton and Gary Lavelle (1983 San Francisco Giants); Tom Henke and Duane Ward (1991 Toronto Blue Jays); Norm Charlton and Rob Dibble (1992 Cincinnati Reds); Matt Lindstrom and Brandon Lyon (2010 Houston Astros).

27 “Tuesday night fights,” Associated Press, July 24, 1986.

28 Indeed, “the proviso prohibiting pitchers from assuming a position other than pitcher more than once in the same inning was added to Rule 3.03 largely to thwart managers like Paul Richards.” David Nemec, The Official Rules of Baseball Illustrated (Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2006), 39.

29 Bob Klapisch, “Clincher Is One for the Books,” in The Amazin’s (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2011), 111.

30 Bud Harrelson with Phil Pepe, Turning Two (New York: St. Martin;s Press, 2012), 203.

31 Episode 16, MLB’s 20 Greatest Games, originally aired April 17, 2011.

32 The Amazin’s, 111.

33 “Orosco Admits Nervousness,” Knight News Service, October 28, 1986.

34 The broadcast is preserved in various ways, one being The New York Mets 1986 World Series Collector’s Edition DVD.

35 It’s also noteworthy that Lee Mazzilli was the Mets’ first-round draft pick in 1973 and returned in August 1986 after being traded away in 1982.

36 Robert McG. Thomas Jr. and Gerald Eskenazi, “This Mitt Calls for a Big Hand,” New York Times, February 25, 1987.

37 “Jesse Orosco,” Santa Barbara Athletic Roundtable web page (sbroundtable.org/hall-of-fame/inductees/athletes/jesse-orosco/).

38 Sam McManis, “They Wanted Out to Escape Doubts,” Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1988.

39 Dylan Hernandez, “Arizona’s Kirk Gibson pulls no punches,” Los Angeles Times, July 3, 2010.

40 McManis, “They Wanted Out to Escape Doubts.”

41 Peter Gammons, “And Here We Go Again,” Sports Illustrated, December 19, 1988. Ben Walker, “Trade talks remain the highlights,” Associated Press, December 4, 1988.

42 Tom Haudricourt, “Team Player: Orosco thankful for opportunity to help Brewers,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 1, 1994: 1B.

43 “Ex-Indian Orosco struggles,” Toledo Blade, October 5, 1996: 26.

44 Tom FitzGerald, “Some memorable quotes from 1991,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 3, 1992.

45 Haudricourt, “Team Player: Orosco thankful for opportunity to help Brewers.”

46 Tom Haudricourt, “Construction ahead: Bando says bullpen will get overhaul,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 1, 1993: 1B.

47 Tom Haudricourt, “Brewers’ roster includes others with shaky futures,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 15, 1994.

48 No one has led either the American or National League with fewer than 75 appearances since 1995.

49 Brad Snyder, “O’s players won over by Johnson’s success,” Baltimore Sun, October 31, 1995.

50 Elliott Teaford, “Johnson Shows Faith in Orosco,” Los Angeles Times, October 6, 1996.

51 David Ginsburg, “Orosco: Still going strong…,” Associated Press, March 5, 1997.

52 Joe Strauss, “Orosco pitches in for record,” Baltimore Sun, August 18, 1999.

53 Ben Walker, “Newly arrived Met traded again,” Associated Press, March 19, 2000.

54 Jason Reid, “Colborn Likes What He Sees From Orosco,” Los Angeles Times, March 16, 2001.

55 Jason Reid, “Old Faithful,” Los Angeles Times, April 21, 2002.

56 Jeff Pearlman, “Old Reliable,” Sports Illustrated, March 10, 2003.

57 Tom Haudricourt, “Lasting Relief,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 21, 2003: 1C.

58 Mark Hale, “Seems Like Old Times — Newest Yankee Orosco Reunited with Mel, Torre,” New York Post, July 24, 2003.

59 “Lefty’s record: 1,252 pitching appearances,” Associated Press, January 21, 2004.

60 Brian Hiro, “Shooting the Breeze: A Q&A with former major league pitcher Jesse Orosco,” San Diego Union-Tribune, September 23, 2012.

61 Facebook Q&A with Jesse Orosco, August 15, 2014.

62 Nolan Ryan (27), Tommy John (26), Jim Kaat, Charlie Hough, and Jamie Moyer (25).

63 Lefty slash line: .210/.287/.301. Righty slash line: .229/.320/.353.

64 Ginsburg, “Baltimore’s Orosco just keeps throwing strikes.”

Full Name

Jesse Russell Orosco

Born

April 21, 1957 at Santa Barbara, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.