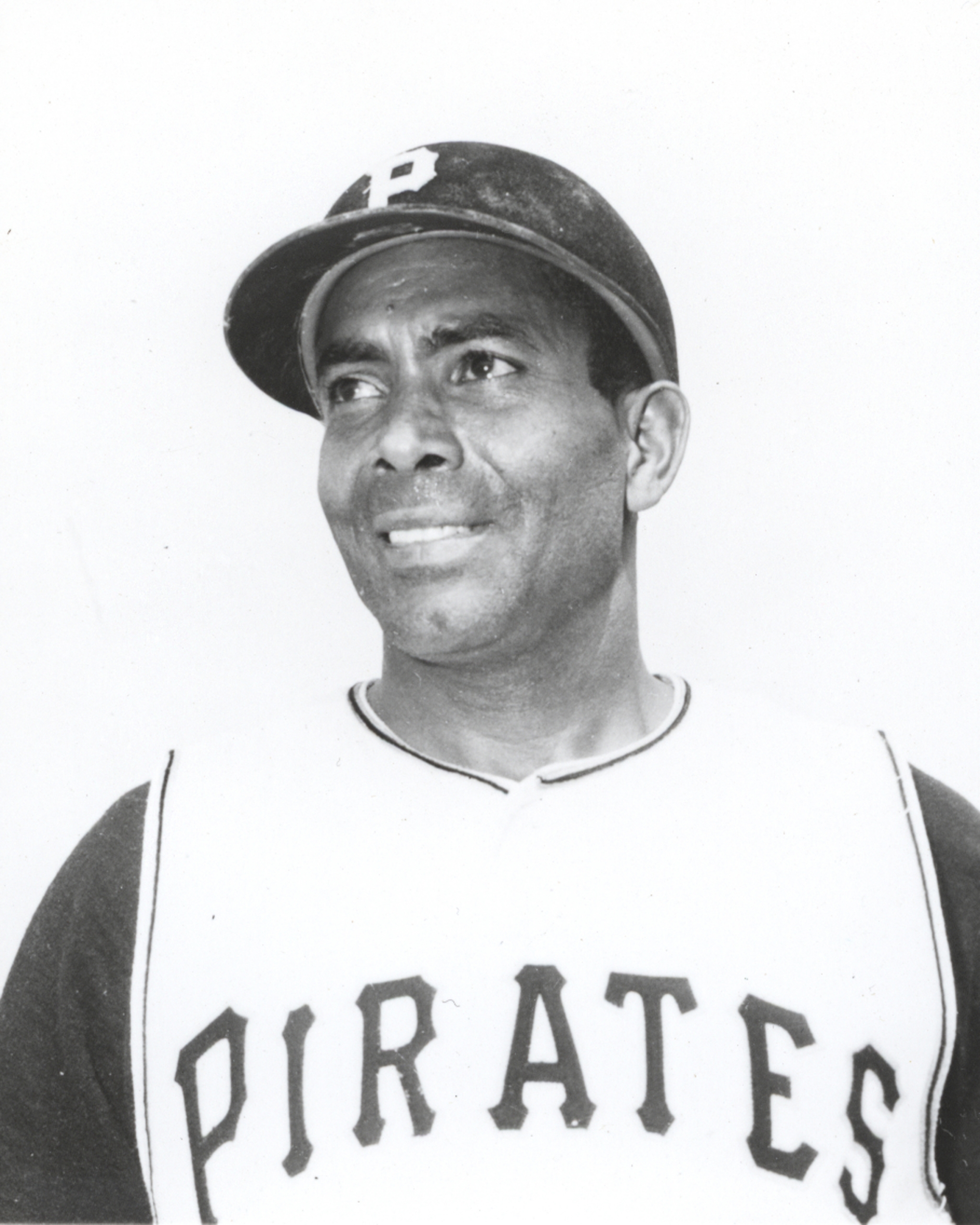

Diomedes Olivo

In Homer’s Iliad, Diomedes was one of the strongest Greek warriors. He was also the youngest — unlike his namesake, Dominican pitcher Diómedes Olivo. Olivo made his big-league debut with the 1960 Pirates at the age of 41. As of 2018, he was still the second-oldest “rookie” in major-league history, behind only Satchel Paige. Like Paige, Olivo had already been a durable star pitcher for many years. And as both Roberto Clemente and Danny Murtaugh are said to have remarked, the man may have been in his 40s, but his arm was 20.1

“Guayubín” (as Olivo was called, for his hometown) earned elite status among his nation’s hurlers during the 1950s. He didn’t even turn pro until his late 20s, but after he did, he pitched in at least six other nations: Puerto Rico, Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Colombia. His pro career — both summer and winter — spanned from 1947 to 1964.

In the majors the lefty’s lifetime record was just 5-6, with a 3.10 ERA in 85 games (1960; 1962-63). During the 1962 season, at the age of 43, Olivo was a revelation to Stateside fans. His fastball was still lively, and “the way that guy throws a curve is murder,” said one unnamed player.2 Although Pittsburgh called Olivo up too late for him to be eligible for the 1960 World Series, he joined Virgil Trucks in throwing batting practice for the team during the Series.3

Diómedes Antonio Olivo Maldonado was born on January 22, 1919 (but rumors persisted that he was actually older). His parents were Arcadio Emilio Olivo Báez and Juana Ramona Maldonado Mejía. “Mamá Juana,” as she was known, died in 1983 at the remarkable age of 103. She had five other children besides Diómedes: sons Arcadio, César Blas, and Federico; daughters Zena and Lucrecia. Federico — known as Chichí (or Chi-Chi in the US) — was also a star pitcher at home who had a short major-league career (1961; 1964-66).

Guayubín (full name San Lorenzo de Guayubín) is the second largest city in Monte Cristi Province, in the northwestern corner of the Dominican Republic. For this reason, Olivo earned another nickname, La Montaña Noroestana: The Northwestern Mountain. Emilio “Cuqui” Córdova, the dean of Dominican baseball writers, made that the subtitle of his short book about Olivo, which became the definitive biography in 2006.

Arcadio Olivo was a cattle rancher. During spring training in 1960, Diómedes recalled through interpreter Román Mejías, “When I put the cows away, I go into town to play. I start when I am 5 or 10 with pickup teams at home in Guayubín.”4 Olivo never picked up more than a smattering of English, relying on teammates such as Mejías, Clemente, Julián Javier, and Al McBean to get his message across. What didn’t need translation, though, was his lively, cheery personality.

In 1990 a Dominican named Dr. José de Jiménez contributed a short but incisive overview of Olivo’s life and career to SABR’s Baseball Research Journal. He wrote, “By 1940 or so the owner of a baseball team in Puerto Plata, a neighboring province, was interested in his services. Since no one knew him in Puerto Plata, the comments among fans and sportswriters included: ‘A great pitcher from Guayubín was signed;’ ‘The pitcher from Guayubín has arrived.’ From that moment on he was baptized as Guayubín Olivo.”

In 2010 Dominican sportswriter Rafael Peña chronicled Olivo’s early years in Dominican ball, noting that he first played in the nation’s capital, Santo Domingo, in 1944.5 That year Olivo was named to the Dominican national team that went to Caracas, Venezuela, for the seventh Amateur World Series. Two years later the Dominicans went to Barranquilla, Colombia, for the Central American and Caribbean Games. Olivo’s standout performance included a 13-inning win over Colombia, in which he allowed just one run on four hits.6

Professional baseball had been on hiatus in the Dominican Republic since 1937, and it did not resume until the summer of 1951 — yet there was still an active club scene. On September 28, 1947, Olivo pitched a no-hitter for Escogido against archrival Licey, the team for which he would later play 11 seasons. That winter he joined Aguadilla of the Puerto Rican Winter League, serving as both pitcher and outfielder. He was a robust man (6-feet-1, 195 pounds) who always took great pride in his hitting.

Olivo said in 1960 that he turned down an opportunity to join the Chicago White Sox in 1948 because he didn’t speak English and didn’t want to come to the United States and play in the minor leagues.7 Pittsburgh sportswriter and broadcaster Myron Cope expanded on this theme in a feature for Sports Illustrated in the summer of 1962. “Back home in Guayubín . . . Olivo owns 500 acres of pasture, 50 cows and 200 acres on which he plans to build a small housing development. He labored hard over the decades, milking cows and pitching baseballs, and though he received occasional feelers from big-league clubs, he turned them down. For one thing, he had no taste for working his way up through the minors; then, too, he feared being shipped to a segregated southern town and felt his ignorance of English would make life doubly hard.”8 Olivo was a coffee-colored man who was termed a “Negro” by US standards.

Instead, his travels took him to Colombia during the summer of 1948, when pro baseball began in that nation. He joined Tejedores (Weavers) de Filtta, an industrial team sponsored by a woolen mill in Barranquilla. In his debut, on June 27, he took a perfect game into the ninth but finished with a two-hitter.9 Colombian baseball historian Raúl Porto said Olivo went back to Filtta in both 1949 and 1950. He was a league all-star in both ’48 and ’49, leading the circuit in strikeouts both years. In 1949, the Tejedores were league champion.

Olivo also played ball in Venezuela during this period. One glimpse comes from May 1950, when the lefty was with Gavilanes, one of three teams in La Liga Occidental, in the western state of Zulia. The Sparrowhawks had a rivalry with Pastora, another team based in the oil city of Maracaibo.10 Negro Leaguers like Max Manning and Terris McDuffie (the latter Olivo’s teammate) were also in the league.11 Sandalio “Sandy” Consuegra, then a Washington Senators farmhand, had also signed with Gavilanes the previous winter. The Cuban spent his $3,000 signing bonus, though, and when he asked Senators owner Clark Griffith to refund it in the spring, Griffith sent Consuegra back to Havana, delaying his big-league debut.12

Olivo remained in Puerto Rico for six more winters. In the 1950-51 season, Aguadilla sold him to San Juan after he suffered seven straight defeats.13 This was a good break because the Senadores were a winning ballclub and the Tiburones (Sharks) were not — in fact, San Juan absorbed Aguadilla for the 1951-52 season. That team won the Puerto Rican championship and went to the Caribbean Series as a result. The tournament was held in Panama City (it is not certain whether Olivo ever played in the Panamanian winter league). The Dominican relieved in two games for Puerto Rico, which went winless, and became the first man from his country to pitch in the Caribbean Series.14

Olivo was among the league leaders in wins (9) and ERA (2.07) for San Juan in 1952-53. That season he conceived a child with a Puerto Rican woman named Crucita Rondón. The boy, Gilberto Rondón, was born on November 18, 1953, in the Bronx, New York. Gil inherited a bit of his father’s talent, as he pitched 19 games for the Astros in 1976 and four for the White Sox in 1979. In later years he became a pitching coach, and one of his stops was with the Nicaraguan national team. He told Nicaraguan baseball historian Tito Rondón (they jokingly called each other “cousin”), “My mom had a thing for ballplayers, and one day she saw Guayubín Olivo, and decided she had to have him, and I was born!” However, Olivo married his wife, Olga Chávez Gómez, in 1953.15 They had three children: Pedro, Olga (known as Titi), and Guillermo.

When pro ball returned to the Dominican Republic in the summer of 1951, Olivo came back home and joined the Licey Tigres. He won the Triple Crown of pitching that year, going 10-5 (in a 54-game schedule), striking out 65, and posting a 1.90 ERA in 128 innings. The 1951 season was tarnished, however, by an out-of-character incident on July 22. Olivo, after arguing a ball-and-strike call with umpire Willis Thompson, threw a ball at the ump’s head, knocking him cold. He was ejected from the stadium and went to jail overnight. Originally, the star pitcher was going to be suspended for the season, but after Licey lobbied intensely, and Olivo himself wrote a public letter of apology in the magazine La Nación, the punishment was reduced to just six games.16

Olivo led the Dominican league in ERA again in both 1952 and 1954. Highlights of the 1954 season included breaking up Negro Leaguer Johnny Wright’s no-hit bid on May 22. His ninth-inning pinch single made a winner of Ewell Blackwell, who was still hanging on (The Whip’s major-league career ended in 1955). One week later Olivo threw a no-hitter of his own over Escogido, which had Hall of Famer Ray Dandridge and another powerful Negro Leaguer, Bob Thurman (who joined the Cincinnati Reds the next year).

After the 1954-55 season ended in Puerto Rico, Olivo came back home to face Japan’s leading team, the Yomiuri Giants, as part of the Giants’ Caribbean tour. The Dominicans took four of five games, losing only the opener as Olivo allowed the two tying runs in the ninth inning and five more in the 10th.17

Shortly thereafter, Olivo played in the US minors for the first time. The absence of Dominican summer ball was clearly a factor. Havana of the International League signed him, as owner Bobby Maduro stocked his team with players who had performed all around the Caribbean.18 However, Olivo pitched just 13 innings in seven games for the Sugar Kings before going to the Mexican League. “My finger is smashed in a car door one day,” he recalled in 1960. “It grow big, but they pitch me. Then they sell me to Mexico City.”19

Olivo spent 1955 through 1958 with the Mexico City Diablos Rojos, with an aggregate record of 34-21. His 15-8, 2.65 performance helped the Red Devils win the league championship in 1956. However, he pitched just five games in Mexico in 1957. The Nicaraguan League (which played in the summers in 1956 and 1957) lured him and Cuban teammate Vicente López away.20 Tito Rondón and his fellow local historian Carlos Mena recalled how Olivo was part of a group called The Lost Squadron that was supposed to reinforce the Bóer club but took weeks to arrive. When they finally did, it inspired Nicaraguan poet Óscar Pérez Valdivia to write verses in their honor. Olivo pitched very well for the Indios, going 8-5, 2.16 in 23 games (16 starts). It was too late for Bóer, though, which lost the championship to León (there were no playoffs). López and Olivo then went back to Mexico.21

Olivo continued to pitch at home after the Dominican season switched to the winter. Myron Cope’s Sports Illustrated story opened with a recollection from a teammate. “In 1959 Dick Stuart, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ nonconformist first baseman, returned from the Dominican Republic Winter League and described to Pirate brass an elderly left-handed pitcher he had seen there. ‘I told them I’d been hitting against this guy for three years down there and I got two hits off him,’ says Stuart. ‘I told them, ‘Sign this guy!’ But you know how it is with me. Anything Stuart says around here, they say forget it.”22

Olivo joined the Poza Rica Petroleros in Mexico for the summer of 1959, which was one of his best as a pro. He was 21-8 with a 3.02 ERA, helping the Petroleros become the league’s champion by leading the league in victories and in strikeouts, with 233 in 247 innings. He set a league record by striking out 16 in a seven-inning game (the opener of a doubleheader).23 He followed up with a typically capable winter for the Tigres (7-6, 2.33).

Howie Haak, the trailblazing scout who opened up all of Latin America, “prevailed upon General Manager Joe L. Brown to take the gamble” in signing Olivo.24 Myron Cope wrote, “Even after the Pirates persuaded Diomedes to sign a contract . . . he failed to report to spring training. The Pirates finally sent a wire: REPORT TO TRAINING CAMP AT ONCE. The other day Diomedes explained through an interpreter that it was the wire that convinced him he was wanted in the U.S.”25

Olivo was impressive in camp, surprising many with his hard stuff and “no trick deliveries.”26 Yet at the beginning of the 1960 season, Pittsburgh decided to keep righty Paul Giel instead. They returned Olivo to Poza Rica, which in turn sold his contract to the Pirates’ top farm club, Columbus in the International League. He pitched well (7-9, 2.88 in 42 games, including 12 starts), and so Pittsburgh called the 41-year-old vet up that September. He made his big-league debut on September 5 — becoming the sixth player (and third pitcher) from the Dominican Republic in The Show.

Olivo pitched in four games for the Pirates that month, with three of those appearances being mop-up duty. His most significant outing came on September 27 at Forbes Field, in a 16-inning win over Cincinnati. He pitched the 10th through the 13th innings, striking out six of the 19 men the Bucs’ pitchers fanned that night.

Although Olivo’s visa was due to expire on October 1, it was extended so he could be on hand for the 1960 World Series.27 After the Pirates defeated the Yankees, the team awarded him a very modest $250 in cash for his September and postseason batting-practice services (Virgil Trucks, who joined the team in August, got $500). That winter Olivo again won the Triple Crown of pitching for Licey. He had 10 victories (against six losses), struck out 160 men — a league record that still stood as of 2018 — in 142 innings, and posted a 1.58 ERA.

Despite this performance, Olivo found himself back at Columbus in 1961. The Pirates had traded for another veteran lefty, Bobby Shantz, the previous December; Olivo was one of the last three men manager Murtaugh cut in spring training. He pitched very well in Triple-A, though, going 11-7 with a 2.01 ERA and 20 saves in 66 games. The Jets won the regular-season pennant (though they were knocked out in the playoffs) and manager Larry Shepard was still talking about the veteran’s importance to the club nearly four years later.28 The IL Writers’ Association voted Olivo as the league’s most valuable pitcher.

Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo was assassinated on May 30, 1961, and the atmosphere in the country remained extremely tense. A nationwide strike and street fighting crippled attendance, and the Dominican League halted the 1961-62 season after the games of December 3.29 Olivo then spent another short stretch in Puerto Rico with San Juan.

Before the 1962 season Baseball Digest issued this scouting report on Olivo: “Superb relief pitcher — perhaps the best in International League. Baffling prospect: Some say he’s as old as 45 — but still pitches with great effectiveness.” Danny Murtaugh kept Olivo with the Pirates that year, and he got his first big-league win at Wrigley Field on April 16. He thrived on frequent work, appearing 62 times, and formed an effective lefty-righty tandem with Elroy Face. He went 5-1 with a 2.77 ERA, also picking up seven saves. Murtaugh frequently used Olivo in a way that would become much more common in the future: as a lefty specialist to get one or two outs. Yet he could also pitch in long relief and got one start, in the season finale.

Dominican League play remained suspended altogether in 1962-63, but exhibition games were still taking place, and Olivo participated.30 He also tended to his farm, although that December cattle rustlers made off with seven of his steers!31 Meanwhile, on November 19 the Pirates traded him to the St. Louis Cardinals along with Dick Groat for pitcher Don Cardwell and infielder Julio Gotay. Olivo started the 1963 season with St. Louis, but things did not go well, as he went 0-5 with a 5.40 ERA in 19 appearances. Manager Johnny Keane also used the vet in a specialist role, giving him just 13⅓ innings total. One of those outings came against the New York Mets at the Polo Grounds on June 7. Ron Taylor had weakened in the ninth inning, putting two runners on. Duke Snider was coming to the plate, and another lefty, Ed Kranepool, was on deck. The Mets won, 3-2, as the Duke hit a three-run homer to end the game.

Keane gave Olivo just two more chances to pitch before the Cardinals sent the 44-year-old down to Triple-A Atlanta in early July. There he enjoyed a late-career highlight, throwing a seven-inning no-hitter on July 22 in the opener of a doubleheader against Toronto. It could have been a perfect game except that he walked Bubba Morton on four pitches with two out in the seventh. Not only that, Olivo singled and scored the game’s only run in the third inning.

Olivo wrapped up his pro career with one final season in Dominican winter ball. He was 9-3, 2.37 in 18 games for Licey. In 2006 his son Guillermo said, “The saddest day of my father’s life was when he played his last game with Licey in 1964. He always felt most comfortable when they called on him to pitch with this team.”32 Olivo’s totals with Licey from 1951 through 1964 were 86-46, 2.11 in 198 games and 1,166⅓ innings pitched. That ERA is second only to Juan Marichal’s 1.87 in league history, but Olivo pitched nearly twice as many innings. The Dominican League named its equivalent of the Cy Young Award for him.

After retiring as a player, Olivo spent seven years scouting for the Cardinals and then one more with the Mets in 1971. He signed at least one major leaguer, Pedro Borbón, Sr.33 He most likely also signed his nephew, Milcíades “Mike” Olivo, who played pro ball from 1964 through 1975, getting as high as Triple-A for a few years. Mike and Chichí Olivo were both part of the Licey team that won the 1971 Caribbean Series for the Dominican Republic, led by player-manager Manny Mota. Forty years later, Mota and Diómedes Olivo remained Licey’s two leading idols.

As of 1977, Olivo was undersecretary of state for sports in the Dominican Republic.34 In an odd coincidence, he and his brother Chichí died less than two weeks apart. José de Jiménez wrote, “On February 15, 1977, at 57 [sic] years of age, [Diómedes] Olivo looked young and strong. That afternoon he went to play softball and early in the evening, reading some comments about the death of his brother Chi-Chi . . . Olivo suffered a sudden heart attack, dying a few minutes later.

“His death was a national catastrophe, the whole country was mourning, there was no music anywhere, the sky was cloudy. . . . The president of the Dominican Republic, Dr. Joaquín Balaguer, sent a telegram of condolence to his widow. To be frank: we all cried.”

In the spring of 1960 Julián Javier (then a Pirates farmhand) discussed Olivo’s stature in the Dominican Republic. Javier said, “His name means something down there like [Willie] Mays and [Mickey] Mantle mean in the United States. If we had Hall of Fame in Dominican, Olivo would be in it.”35 The Dominican Sporting Hall of Fame was established in 1967, and in 1973 it inducted Guayubín Olivo. Judging by the number of stories that are still written about him, his legend at home has not lost any luster since.

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Eddy Olivo Cruz for providing the family tree compiled by his second cousin, Emilio Olivo (nephew of Diómedes Olivo). Continued thanks to Raúl Porto (Colombian information) and to SABR member Tito Rondón.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, http://www.pabellondelafamadeportedom.com, and the following:

Córdova, Cuqui. Guayubín Olivo: La Montaña Noroestana. Issue 5 of Historia del Béisbol Dominicano (Santo Domingo: Revista Historia del Béisbol, 2006).

De Jiménez, José. “The Great Dominican, Diómedes Olivo.” Baseball Research Journal, Volume 20. Society for American Baseball Research: 1990: 91-92.

Crescioni Benítez, José A. El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997).

Bjarkman, Peter C. Baseball with a Latin Beat (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1994).

Bjarkman, Peter C. Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005).

Notes

1 “Pirate Profiles,” Evening Standard (Uniontown, Pennsylvania), April 3, 1962: 20.

2 United Press International, “Buc Rookie’s Oral English Sparse, but His Baseball ‘English’ Is Most Fluent,” Daily Courier (Connellsville, Pennsylvania), July 7, 1962: 7.

3 Lester J. Biederman, “Olivo, Trucks New York-Bound, Too,” Pittsburgh Press, October 6, 1960.

4 Associated Press, “Old Buc Rookie Has Been Around,” Evening Sun (Hanover, Pennsylvania), April 1, 1960: 16.

5 Rafael V. Peña. “Guayubín Olivo.” Blog of Asociación de Cronistas Deportivas de Santo Domingo — Filial Nueva York, May 14, 2010. (http://acdny.blogspot.com/2010/05/guayubin-olivo.html)

6 Cuqui Córdova, “La crónica de los martes,” Listín Diario (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), December 9, 2008.

7 Red Smith, “Can Youthful Pirates Grow Up in 1960?”, New York Herald Tribune, August 7, 1960.

8 Myron Cope, “An Elderly Diomedes In The Big Show,” Sports Illustrated, July 16, 1962.

9 Córdova.

10 Alexis Salas H. Los Eternos Rivales: 1908-1988 (Caracas, Venezuela: Seguros Caracas, 1988, 112).

11 “Sulia [sic] State League Opens,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1950: 48.

12 The Sporting News, April 19, 1950: 52. Jack Hand, Associated Press, “Cuban Talent Pays Off For Senators,” Danville (Virginia) Bee, June 22, 1950: 22.

13 Santiago Llorens, “Yankee Rookie Tops Star Poll in Puerto Rico,” The Sporting News, January 3, 1951: 25.

14 Bienvenido Rojas, “Serie del Caribe: Olivo, primer criollo en lanzar,” Diario Libre (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), January 26, 2007.

15 Bob Broeg, “He Comes on Strong,” Baseball Digest, July 1963: 32.

16 Rafael Baldayac, “José Offerman revive caso Guayubín Olivo,” La Información (Santiago, Dominican Republic), January 28, 2010.

17 Robert K. Fitts. Wally Yonamine (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 183.

18 Pedro Galiana, “Cubans Rolling on Warm-Up in Winter Loops,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1955: 29.

19 “Sportswriters Chat with Olivo via Mejias,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 2, 1960: 15.

20 Miguel A. Calzadilla, “Trautman Probes Reports of Raids,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1957: 36.

21 Miguel A. Calzadilla, “Sultans Renew Cincy Pact,” The Sporting News, August 21, 1957: 46.

22 Cope.

23 “Ramon Lopez in Whiff Show,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1964: 35.

24 Harry Keck, “How Old Is Olivo? ‘About 42,’ He Says,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1962: 17.

25 Cope, op. cit.

26 Les Biederman, “Olivo, Pirates’ 40-Year-Old Rookie, Dominican Hill Ace,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1960: 15.

27 “Spanish Rolls, Pirate Olivo To See Series,” Pittsburgh Press, September 6, 1960.

28 “Sam Jones to Lead Pennant Push by Jets, Shepard Says,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1965: 35.

29 “Political Turmoil Forces Dominican League to Fold,” The Sporting News, December 13, 1961: 34.

30 Associated Press, “Alou Fined for Winter Activities,” Baltimore Sun, February 5, 1963: 17.

31 Associated Press, “Olivo Is Victim,” Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), December 19, 1962: 29.

32 Nathaneal Pérez Neró, “El Licey bautiza ‘dogout’ con el nombre de Guayubín Olivo,” Diario Libre (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), December 12, 2006.

33 Questionnaire received by Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee. Caveat: in retrospect, Nelson has not been able to confirm the other two names listed on the questionnaire, Larry Dick and Monchín Pichardo, as being Cardinals scouts. However, Pichardo became president and general manager of Licey in 1963-64, and Borbón Sr. spent his entire Dominican career with Licey.

34 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, March 5, 1977: 54.

35 Biederman, “Olivo, Pirates’ 40-Year-Old Rookie, Dominican Hill Ace.”

Full Name

Diomedes Antonio Olivo Maldonado

Born

January 22, 1919 at Guayubin, Monte Cristi (D.R.)

Died

February 15, 1977 at Santo Domingo, Distrito Nacional (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.