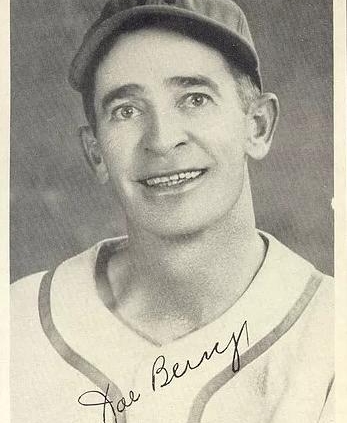

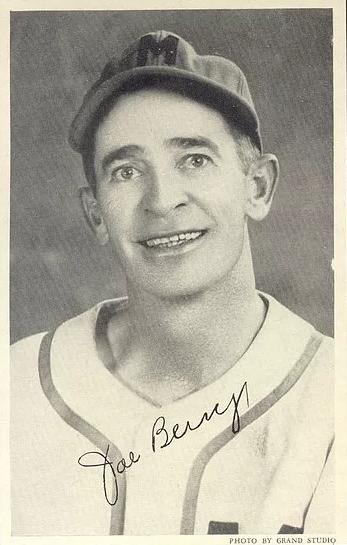

Joe Berry

Pitcher Joe Berry was variously described as little, skinny, slight, bandy-legged, and pint-sized. Berry was officially listed as 5-feet-10 and 145 pounds, but Jim Coleman of The Sporting News wrote that “he was only 135 pounds and looks as harmless as a dead moth.”1 So small was Joe that in 1942 during an exhibition game against the New York Yankees at Bader Field in Atlantic City, New Jersey, he went into the stretch and a gust of wind blew him right off the pitcher’s mound. The umpires ruled it an “act-of-God balk” and Berry climbed back up on the mound, braced himself, and continued pitching.2

Pitcher Joe Berry was variously described as little, skinny, slight, bandy-legged, and pint-sized. Berry was officially listed as 5-feet-10 and 145 pounds, but Jim Coleman of The Sporting News wrote that “he was only 135 pounds and looks as harmless as a dead moth.”1 So small was Joe that in 1942 during an exhibition game against the New York Yankees at Bader Field in Atlantic City, New Jersey, he went into the stretch and a gust of wind blew him right off the pitcher’s mound. The umpires ruled it an “act-of-God balk” and Berry climbed back up on the mound, braced himself, and continued pitching.2

The little man in the baggy uniform knew he didn’t have the best stuff in the world, so he learned a variety of ways to fool hitters and play with their minds to get them out. Before he threw a pitch, he would make the batter wait, walking around behind the mound, rubbing up the ball, adjusting his cap, tugging at his loose-fitting jersey, and going to his mouth as if he were about to load up a spitball. Finally, he would go into his “twitchy, itchy” windup and serve up a variety of slow curves, screwballs, knuckleballs, and changeups. Berry’s mound antics earned him the nickname Jittery Joe.3

Berry’s tour of the minor leagues began in 1927, when he was 22 years old. It reads like the itinerary of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. He had stops in Laurel, Gulfport, and Vicksburg, Mississippi; Pine Bluff and Fort Smith, Arkansas; Macon, Georgia; Joplin, Missouri; and Ponca City, Oklahoma, before settling in for six productive years with the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. World War II gave the aging hurler his shot at the top level. As front-line players were drafted into the armed services, major-league teams looked to the minors to fill out their rosters. That was where they found Berry, and he eventually made the most of his opportunity. He used his deceptiveness and assortment of pitches to become, at 39 years old, the best relief pitcher in the American League for two seasons, 1944 and ’45.

Jonas Arthur Berry was born on December 16, 1904, in Huntsville, Arkansas, in the Ozark Mountain region. At the time of his birth, Huntsville was a town of about 500. Joe was the eighth of nine children born to Jonas “Joan” Berry and Lydia (Hudson) Berry. Joan Berry was a part-time farmer who was the sheriff of Madison County for 20 years. The Berrys were descendants of William Martin Berry and his son Hugh Samuel Berry, who were executed in the notorious Huntsville Massacre of January 10, 1863. Nine Huntsville residents, suspected of collaborating with the enemy and harassing Union sympathizers, were executed on the orders of Union Lieutenant Colonel Elias Briggs Baldwin.4

Like Joe, most of the children in the family were small, but according to his nephew Ben Berry, Joe was the “most feared kid in school. He was kind, but if he ever saw a bully taking advantage of someone, the bully better look out.”5 Once Joe’s little brother Lee Roy got into a scrape with a bigger kid and Joe came to his rescue. Since it was summer and all the boys were running around barefoot, Joe approached the hulking bully with a rock hidden behind his back and when the brute came after him, he smashed the rock onto the boy’s exposed foot, ending the bully’s desire to continue picking on members of the Berry family.6

Berry developed a reputation for being a good pitcher with semipro teams in the Ozarks. He signed his first professional contract with Laurel in the Class D Cotton States League in 1927, when he was 22. He toiled for six years with various franchises in the league, accruing 89 victories, before moving up to Joplin in the Class C Western Association. After a season back in the Cotton States League with the Chicago Cubs’ affiliate in Ponca City, Oklahoma, Berry got a chance to attract more notice in 1936 when the Cubs assigned him to Los Angeles of the PCL. That provided a leap to Double-A, then the highest classification, and the opportunity to be noticed by big-city fans and newspapers.

By then Berry was 31 (born in 1904), nearly three years older than the average PCL player. He was hardly a highly touted prospect, so both the team and Joe himself fibbed about his age. Newspapers at the time reported it as 25.7 Berry claimed to have been born in 1907, shaving off three years.8

Jittery Joe pitched very well for the Angels. Over six seasons, mostly working out of the bullpen, he appeared in 258 games and compiled a 59-53 record and a 3.50 ERA. He was a very popular player in Los Angeles because of his small stature, slick fielding, assortment of pitches, mound antics, and mostly effective pitching.

One quirk in Berry’s repertoire always got the fans cheering. When a runner was on second base, Joe liked to step off the mound and grab the rosin bag, dust his hands and arms, and then toss the bag a little farther from the mound and a little closer to second base. He would then climb on the mound, step off again, go back to the rosin bag and again toss it casually just a little closer to second base. Once he thought the rosin bag was close enough to second and the runner was far enough off the second-base bag, he would repeat the action, but instead of grabbing the rosin bag, he would take off for the runner to catch him napping. Berry never caught anybody, but the act kept the fans entertained.9

On July 10, 1938, Berry pitched the first no-hitter of his career, a seven-inning affair in the second game of a doubleheader against the Oakland Oaks at Oaks Park. He won the game 4-0 and allowed only two baserunners through walks. In late July the team and fans held an event for Joe designated Arkansas Day. (Former Arkansas residents were invited to attend free.) Berry was presented with “a flock of gifts,” including an Arkansas mule.10 He pitched the second game of the doubleheader that day and responded by shutting out the Portland Beavers on two hits, winning 6-0. Newspapers featured a picture of a smiling Joe in full uniform astride the mule.11

Berry reported, “The fans hollered for me to ride it, figuring I’d fall off, but one thing I can do is ride. So, I hopped up on that mule and tried to dig my cleats into him, so he’d start bucking. Laziest old mule I ever saw. Wouldn’t do nothing but lope along. He was older than I was.”12

Berry had an offseason in 1941 in Los Angeles. His ERA ballooned to 5.26. The Cubs decided to demote him to the Tulsa Oilers of the Class A1 Texas League for the 1942 season. The demotion proved to be the ticket to the major leagues for Berry, by then 37. He had a great year in Tulsa, going 18-8 with a 1.88 ERA. On August 11 Berry pitched a nine-inning no-hitter against the Oklahoma City Indians, winning 1-0 when his team scored a run in the bottom of the ninth inning. He struck out eight and walked only one.13

The Cubs were desperate for pitching help to replace players being called to military duty for World War II. They reached down to Tulsa and called up a pitcher from their system who was conveniently too old for military service — Jittery Joe Berry.

Berry made his major-league debut on September 6, 1942, in game two of a doubleheader against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. He relieved Bill Fleming in the eighth inning with the Cubs trailing 3-0. It did not go well. Berry retired the first batter he faced, Elbie Fletcher, but Vince DiMaggio tripled, Al Lopez singled, and Frankie Gustine doubled in rapid succession. Before he could escape the inning, Berry had given up four hits and two runs. On September 13 Berry had a similar outing, giving up three hits and two runs to the Boston Braves in another one-inning relief stint. Berry’s first big-league experience was over.

In 1943 Berry went to spring training with the Cubs but was shipped to Milwaukee of the American Association on the last day of camp. He had an excellent year at Milwaukee, going 18-10, mostly as a starting pitcher. In Philadelphia, the Athletics’ owner-manager, Connie Mack, noticed. He purchased Berry’s contract from Milwaukee and penciled in his name as a key reliever for his team in 1944.

Berry was by then 39, although the newspapers reported his age as 36.14 He impressed everyone at spring training with his assorted deliveries — “no two pitches he makes are exactly alike”15 — and his willingness to pitch nearly every day. “That’s just the kind of work I like,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “The more I pitch the better I like it.”16

Berry opened the season impressively, pitching eight shutout innings and earning two wins and a save (although saves were not yet an official statistic) in his first three relief outings. He was effective in relief throughout the season, appearing in 53 games, finishing a league-leading 47, and saving a league-leading 12 (as calculated retroactively). His ERA was an outstanding 1.94 and ERA+ 178. He wrapped up his first full season in the major leagues with a flourish, pitching in both games of a doubleheader on September 29 and again on October 1. These were the last four games of the A’s season, and in them Berry pitched a total of 11 innings, giving up just four hits and no runs. The A’s won three of the games; the other was called after nine innings because of rain with the score tied 1-1. In those three games, Berry was credited with two wins and a save. Philadelphia finished the season at 77-82-1 in fifth place in the American League, their highest finish in 10 years.

Berry’s fine pitching, advanced age, small stature, and quirky mound antics got him some notice in the national press. And the veteran also apparently had a way with a story. Red Smith, writing in Baseball Digest, recorded this Jittery Joe tale:

“Wildest ballgame I ever did see is back a dozen or so years ago in Pine Bluff, Ark. Ask Wally Moses about it. He was playing for Monroe, La. against us. Monroe’s got Jackie Reed pitching against us. … He was a screwball pitcher that did everything to the ball. Packed the ball with resin or dirt, shined one side of the ball, scuffed the cover, doctored it any way he could. Well, this day he’s got a lead of 13 to 1 going into the last of the ninth. Old Pop Kelchner’s managing Monroe.

Their batboy, figuring the game’s wrapped up, stacks all the bats and gets everything ready so they can pull out fast. But we got two-three hits off Reed, then he gets a couple guys out. Then we start going. Pretty soon we knock Reed out of there. We keep working on the next pitcher. We got a guy named Mercer Harris and he gets what I think must be a record to this day. This Mercer Harris comes up three times in the inning and gets three triples. Lots of guys don’t get three triples in a season. We score thirteen runs that inning and win the ball game, 14-13.

That Kelchner like to went crazy. He kicked the bat rack over, threw all the bats all over the field, and the last time I saw him he was taking out after that kid that racked up the bats, swearing he’d lynch him for putting the whammy on ’em.”17

Berry continued to put the “whammy” on AL hitters as a 40-year-old in 1945. He led the league with 52 appearances and 40 games finished. His ERA did rise a bit, to 2.35, and his saves were down to five, as the Athletics returned to their losing ways and dropped to the AL cellar. On July 21 Berry pitched 11 shutout innings in relief of Russ Christopher against the Detroit Tigers in the longest game ever played at Shibe Park. Berry came in to begin the 14th inning and shut the Tigers down on six hits until the game was called because of darkness after 24 innings. Berry was particularly effective against the New York Yankees that season, pitching 17⅔ scoreless innings against them in five outings from April 26 through June 22. He finished the year with a 1.86 ERA in 10 appearances against the Yankees.

In 1945 Athletics pitching coach Earle Brucker told The Sporting News how Jittery Joe would double-cross sign-stealing coaches like the Yankees’ Art Fletcher. “He gets a hitter two-and-two,” Brucker explained, “and if he knows the coach is watching him, he’ll stick [his] thumb up in the air when he starts his windup, tipping off the curve. But he’s a mean deceitful little conniver. The batter gets all set for the curve — and then stands there, frozen and quivering, when Joe sneaks a fast ball past him.”18

In 1946, with players returning to major-league rosters after their military service ended, Berry found himself in a roster squeeze in Philadelphia. Pitchers like Phil Marchildon, Dick Fowler, and Bob Savage were welcomed back to the A’s fold. While Joe was still pitching effectively, there was no room for him in the A’s bullpen. He was sold to the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League at cutdown time in May. Berry appeared in 16 games for Toronto, but his major-league journey was not over yet.

On July 1 Berry was tossing the ball in the Toronto bullpen before a doubleheader when the Maple Leafs’ traveling secretary, James Gruzdis, yelled to him from the dugout, “You’ve been sold to the Cleveland Indians. Hurry up and get packed — you’re due to report this afternoon.”19 Berry hurried to his room at the Royal York in Toronto, packed, and caught a flight to Cleveland. Landing at 4:38, he headed to Municipal Stadium, where he was greeted by Lou Boudreau. The Indians manager told him to be ready to pitch if he was needed that night against the St. Louis Browns.

Berry was summoned into the game in the sixth inning with one man out, a runner on third, and the score tied, 4-4. He escaped the inning by inducing two groundouts and then drove in the go-ahead run with a single in the bottom of the sixth. Berry shut down the Browns on three hits over the final three innings, earning his first win for Cleveland while becoming the only pitcher to warm up for one team in one ballpark in one country and then win a game for another team in another ballpark in another country on the same day.20

Except for a bad outing on July 4, Berry pitched effectively for Cleveland in 21 appearances in 1946. His best performance came on September 3, against the Browns, when he relieved a struggling Charlie Gassaway in the fourth inning and pitched six innings of one-hit, shutout relief to earn the victory, 7-3. He finished the year with a 3-6 record and 3.38 ERA for Cleveland.

In 1947 Berry went to spring training in Tucson, Arizona, with the Indians, but he was sold to Oklahoma City of the Texas League on April 5. This marked the end of Jittery Joe’s major-league career, but not the end of his baseball odyssey. Berry pitched for four more years, adding a new list of towns to his already lengthy itinerary. In 1947 he worked for Oklahoma City and Shreveport, Louisiana. In 1948 he made a return trip to Tulsa. After sitting out the 1949 season, Berry returned as player-manager of the Vernon (Texas) Dusters of the Class D Longhorn League for 1950 and part of the 1951 season. Fired at the end of July 1951, he signed with the Corpus Christi Aces in the Class B Gulf Coast League, for whom he appeared in 16 games and compiled a 3-0 record.

After the 1951 season, Berry finally called it quits. He had pitched professionally for 24 seasons and for 21 franchises on every conceivable level from one end of the country to the other.

After his playing days, Berry settled in Fullerton, California, where he found work as a calender man21 with the Kirk-Hill Rubber Company. He had married Harleen Roberts in 1936. The couple had three children. Harleen was a schoolteacher. Joe was still very popular with Los Angeles Angels fans and participated in Old-Timer’s Games in his retirement. Berry’s nephew, Clyde Berry, a second baseman, played briefly in the Chicago White Sox organization.

On September 25, 1958, Berry picked up his wife from school. As he drove home, he was involved in a collision with another automobile. Berry was thrown from his car and suffered a fractured skull and other injuries. Surgery was unsuccessful; on September 27 he died from his injuries. Joe Berry was 53 years old. He was buried back home in the Huntsville Cemetery. His headstone reads, “Jittery Joe Berry December 16, 1904 — September 27, 1958.” The nickname and his actual date of birth were preserved for posterity.

Little Joe Berry battled big bullies from the schoolyard to the professional baseball diamond. Philadelphia Athletics pitcher Jesse Flores told Red Smith this tale about his teammate:

“Greatest exhibition of relief pitching I ever saw was given by Jittery Joe Berry when we both pitched for Los Angeles. Berry came in with the bases filled, two out and Hal Padgett, a good hitter, at bat. His first three pitches were balls. Joe walked to the plate. ‘You big dope,’ he told Padgett, ‘you better start swinging because I ain’t gonna walk you.’ Then he struck him out on three straight pitches.”22

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.com.

Notes

1 Jim Coleman, “Jittery Joe Warms Up in Toronto, Wins in Cleveland,” The Sporting News, July 17, 1946: 8.

2 Red Smith, “Berry Blooms in A’s Pitching Patch; Rubber Arm Bounces Batters in a Pinch,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1944: 4.

3 Jim Yeager, “Arkansas’ Jonas Berry, Baseball’s ‘Jittery Joe,’” Arkansas’ Jonas Berry, Baseball’s “Jittery Joe” | Only In Arkansas, accessed on September 7, 2021.

4 Kevin Hatfield, “Huntsville Massacre,” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/huntsville-massacre-3795/, accessed on August 26, 2021. Lt. Col. Baldwin was arrested and held for trial in front of a military commission for “violation of the 6th Article of War for the murder of prisoners of war.” But many of the witnesses called were either too ill or on military duty and failed to attend. Charges against Baldwin were dismissed, and he was discharged.

5 Ben Berry, “Dynamite in a Small Package,” Searcy Living, http://www.searcyliving.net/au08/jitteryjoe.html, accessed on August 18, 2021.

6 Ben Berry, “Dynamite in a Small Package.”

7 “Sox Send Hurler Joe Salveson to Seraphs,” Los Angeles Times, April 20, 1936: 23.

8 J.G. Preston, “The Oldest Players to Make Their Debut in the Major Leagues,” The JG Preston Experience, https://prestonjg.wordpress.com/2013/09/15/the-oldest-players-to-make-their-debut-in-the-major-leagues-satchel-paige-and-the-rest/, accessed on September 3, 2021.

9 Joe Kelly, “Between the Lines,” Lubbock (Texas) Avalanche-Journal, June 13, 1954: 13.

10 Bob Ray, “Berry Hurls 6-0 Victory,” Los Angeles Times, August 1, 1938: 31.

11 Ray, “Berry Hurls 6-0 Victory.”

12 Red Smith, “Berry Blooms in A’s Pitching Patch.”

13 “Berry Fashions No Hit, 1-0 Win,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 12, 1942: 11.

14 Stan Baumgartner, “Joe Berry Impresses at Athletics Camp, Likely Relief Pitcher,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 15, 1944: 28.

15 Art Morrow, “Game Halted as A’s Lead Toronto, 3-1,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 12, 1944: 26.

16. Baumgartner, “Joe Berry Impresses at Athletics Camp.”

17 Red Smith, “Heard in the Clubhouse,” Baseball Digest, August 1944: 63.

18 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Double-Crossing the Sign Swipers,” The Sporting News, March 22, 1945: 2.

19 Coleman, “Jittery Joe Warms up in Toronto.”

20 Berry, “Dynamite in a Small Package.”

21 A calender man worked the huge rollers used to smooth and flatten sheets of rubber.

22 Red Smith, “Giving Relief,” Baseball Digest, September 1945: 20.

Full Name

Jonas Arthur Berry

Born

December 16, 1904 at Huntsville, AR (USA)

Died

September 27, 1958 at Anaheim, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.