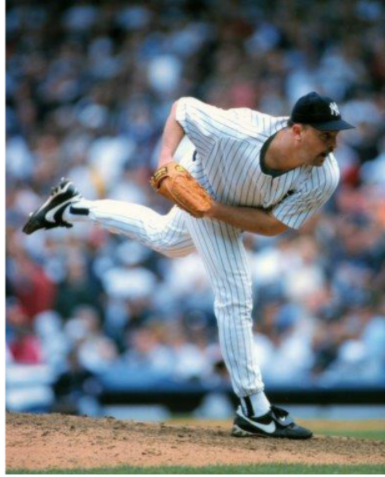

David Wells

You have to love a guy who takes the mound in the House That Ruth Built wearing a Cap That Ruth Wore.

David Wells did just that at Yankee Stadium on June 28, 1997, when he took the hill to pitch against Cleveland sporting his Yankee pinstripes and his Yankee cap. The problem was that it wasn’t the standard-issue model his teammates were wearing; it was a cap Ruth wore in 1934 that Wells had purchased for $35,000. Yankees manager Joe Torre found out about it after the first inning and ordered Wells to remove it.1

Such was the career of David Lee “Boomer” Wells, whose reverence for New York Yankees traditions contrasted with his iconoclastic attitude toward just about everything else during his 21-year major-league career with nine different teams. He retired with a career 239-157 career won-lost record (.604 winning percentage), a 10-5 record in the playoffs, two World Series rings, and a perfect game.

Wells was born on May 20, 1963, in Torrance, California. His childhood was, to say the least, unconventional. His mother, Eugenia Ann Wells, was a biker chick with the handle Attitude Annie. Annie wasn’t exactly your typical suburban soccer mom as she had five children from four different men. Wells didn’t meet his father, David Pritt, until he was 22 years old.

Growing up, Wells was the only kid in the neighborhood, and possibly in the country, who could bring the Hell’s Angels to his Little League games. Annie’s boyfriend was Crazy Charlie Mendez, a longtime member of the San Diego chapter, and he would bring his confreres to Wells’s games when he pitched. Not only that, the bikers would each give him a dollar (or 25 cents) for every batter he struck out, and $5 (or $1) every time he won.1 And no matter how much the gang members owed him, he never worried about them welching.

“I could pull in $100 a game, and nobody dared screw around with me,” said Wells. “Try, and I’d say, ‘I’ll get my mom’s boyfriend on you.’”2

Charlie didn’t generally abuse Wells, but he wasn’t afraid to smack him if it meant teaching an important life lesson. Once, when he was 12, Wells walked into the kitchen with his fists up; Charlie greeted him with a left hook. “I said, ‘What did you do that for,’” recalled Wells. “He said, ‘Anytime you put your hands up, you’d better use ’em.’ Other than that, he treated me like a king.”3

Wells pitched for a very good Point Loma High School team that competed for the city championship in 1981 and 1982. If some of the stories about his high-school career are true, his coach may very well have ended up with ulcers. He once told teammates during a game that he was going to deliberately walk the bases loaded, then strike out the side on nine pitches, and proceeded to do just that. On another occasion, Wells was going for a second perfect game when the first baseman told Wells he needed one out for the gem. Coach Steve Saracino heard the player and told him he was off the team if the batter got a hit. Well, the batter did get a hit, and Saracino followed through on his threat. The following Monday, Wells convinced his teammates to boycott practice unless the first baseman was reinstated. Saracino relented.

Wells was the starter for two championship games, losing in 1981 to Darren Balsley and Mt. Carmel High School, then coming back to beat Mt. Carmel the following year. Balsley was Wells’s pitching coach during both of his stints with the San Diego Padres.

That ability to pitch in critical ballgames and being chosen for the American Baseball Coaches Association second All-American team may have encouraged the Toronto Blue Jays to pick Wells in the second round of the 1982 amateur draft. Being drafted by a team that had one of our feathered friends as a nickname didn’t impress Boomer.

“I said, ‘Man, if I ever sign, I’m never playing for those guys, ever,’” Wells said. “A Blue Jay? I mean, a bird? And I signed with the Blue Jays out of high school. I’m like, how cliché is that?”4

Wells’s first stop up the minor-league ladder didn’t make him very happy, either. The Jays sent him to the Medicine Hat (Alberta) Blue Jays of the rookie-level Pioneer League, where as a 19-year-old he had a moderately successful season, going 4-3 but with a 5.18 ERA. He walked 32 and struck out 53 in 64⅓ innings pitched.

Wells continued his climb through the minor-league ranks south of the 49th Parallel over the next few years as he developed his skills as a pitcher. In 1984 his ERA improved to 3.73, to go along with a 6-5 pitching record with Kinston of the Class-A Carolina League He had only 15 appearances in 1984, seven with Kinston and eight with Knoxville of the Double-A Southern League before becoming just the third pitcher in history to undergo Tommy John surgery. (The first two were Brent Strom of San Diego in 1977 and, of course, Tommy John.) The operation caused Wells to miss all of the 1985 season.

When Wells returned in 1986, he had to start again from the beginning, and advanced from Single A to Double A before landing with the Jays’ Triple-A International League affiliate in Syracuse, where he spent parts of the next three seasons. He got called up to the Jays in the middle of the 1987 season and made a less than memorable major-league debut on June 30, 1987, against the New York Yankees. He gave up four earned runs in four innings of work and took the loss in a 4-0 Yankees win. Then he decided to celebrate July 4 in Kansas City by getting lit up for five earned runs in only 1⅓ innings for his second loss as the Jays got Royally routed 9-1. Wells found a plane ticket back to Syracuse in his locker after that game.

He returned as a September call-up as the Jays battled the Detroit Tigers for the East Division crown. The team used him as a reliever, and that’s how he got his first major-league victory. On September 2 he came in against the California Angels with two out in the top of the eighth inning with the score tied 5-5 in Toronto’s Exhibition Stadium. George Bell’s two-run home run in the bottom of the inning put Toronto ahead, and Wells got the victory despite giving up an earned run in the ninth.

The Jays weren’t afraid to use Wells in critical situations as the season wound down. Holding a one-game lead over Detroit going into the last weekend of the season, Toronto visited Tiger Stadium for the three-game series that would decide the division champion. In the first game, on October 2, Wells took over for Jim Clancy, who had given up four runs in two-plus innings of work. He held the Tigers scoreless the rest of the way, but the Jays still lost 4-3. Detroit ended up winning the crown.

Despite being the subject of offseason trade rumors – the Associated Press said he may have been part of a trade to the Yankees – Wells started the 1988 season in the Jays bullpen.5 He still had his rookie status, and in a July 10 article, Associated Press sportswriter Jim Donaghy chose Wells as the midseason top rookie in the American League with a 3-5 record and four saves.6 Any chance Donaghy ever had of being offered a job as a scout quickly went out the window as the Jays announced the next day that they had sent Wells down to Syracuse the next day. They recalled him in late August, and he pitched in four games from August 26 until the end of the season without any decisions or saves.

Wells began the 1990 season in the bullpen, but a slump by teammate John Cerutti changed the direction of Wells’s career. Cerutti lost five of his first six decisions, so Jays manager Cito Gaston decided that some time in the bullpen would help him out of his funk; Gaston promoted Wells into the starting rotation on May 24 as a temporary measure. Even Wells expected to return to the bullpen. “Several times throughout June, he told reporters it was only a matter of time until he returned to the bullpen,” wrote Mike DiGiovanna in the Los Angeles Times.7

Wells’s assignment to the rotation turned out to be as temporary a measure as income tax. He was a starter for the rest of the season, finishing the year with an 11-6 record – his first win was in relief – with a 3.14 ERA and 189 innings pitched.

The 1991 Blue Jays began a string of three straight American League East Division titles, but for Wells the season had mixed results. On August 9 he and Gaston got into an argument on the mound after Wells had given up five runs on nine hits against the Boston Red Sox, with Wells throwing the ball away as he stormed off the mound. The two later fought under the stands.

The spat and scuffle happened during a period when Wells lost six of eight decisions between July 29 and September 8, during which his ERA rose from 2.73 to 3.75, more than one run per nine innings. Not surprisingly, Wells was relegated to the bullpen for the rest of the season.

After winning the American League East in 1985, 1989, and 1991 only to lose in the ALCS, the Blue Jays finally went all the way in 1992. They not only reached the World Series for the first time, but defeated the Atlanta Braves in six games to win it all.

For Wells, a season that culminated a championship ring got off to a lucrative start when the Jays more than doubled his salary from $800,000 to $2,063,000. That was a pretty good raise for a swingman.8 In fact, he did so much swinging between the bullpen and the rotation that he could easily have had motion sickness. He started in his first two appearances, defeating Baltimore 3-1, and losing 1-0 to the Red Sox, which earned a ticket to the relief corps.9 He returned to the rotation on June 24, and was inconsistent, going 5-6 between then and August 25. A 6-3 loss to the White Sox in which he gave up all six runs (three earned) convinced Gaston that Wells could better serve the team as a reliever, where he remained the rest of the season. He finished with a 7-9 record and a 5.40 ERA. He didn’t play in the ALCS, which the Jays won in six games over Oakland, but he was excellent in the fall classic, appearing in four games and giving up only one hit and no runs in 4⅓ innings of relief.

After the season Wells felt that he had earned the right to be a starter. “I think I proved something not pitching for 21 days and getting into the World Series and showing I can pitch,” he said.10 Instead, the Jays gave him his unconditional release on March 30, 1993. In a 2000 Sports Illustrated article on Wells, former Blue Jays general manager Gord Ash explained that the team had grown tired of his inconsistency, his temper, his weight and his fondness for drinking beer – lots and lots of beer. “We did everything we could to control him,” said Ash.11

Whatever bothered the Blue Jays didn’t seem to be of concern to other teams, as Wells garnered interest from 16 other clubs within three days of his release. He signed a one-year deal with the Detroit Tigers on April 3 that included a $900,000 salary, plus $550,000 in bonus incentives. He also became a starter on a team that had the worst team ERA (4.60) in the American League in 1992.

Sparky Anderson was Detroit’s manager, and besides having a penchant for removing pitchers from games early – he was nicknamed Captain Hook – he also let players be themselves, and Wells thrived without being pressured to conform. He went 11-9, although his ERA was still high at 4.19, and struck out 139 batters in 187 innings.

Those numbers proved lucrative to Wells; before the 1994 season he signed a three-year contract with Detroit worth $7.5 million. But as is so often the case, fate intervened to make management gnash its teeth over the deal. Wells went on the disabled list on April 19 to recover from having bone chips removed from his elbow. He may as well have stayed there because when he returned to the mound in June, he proceeded to lose his next three starts, and finished the strike-shortened season with a 5-7 record and a 3.96 ERA.

The 1995 season almost changed baseball history. The Tigers were going nowhere and the Yankees, in the middle of a playoff hunt, wanted Wells for their rotation, and were willing to trade a minor-league starter for him. That minor leaguer, according to Jerry Green of the Detroit News, was somebody named Mariano Rivera. Yankees general manager Gene Michael eventually nixed the deal after Rivera’s fastball began showing improvement. Instead, the Tigers traded Wells to the eventual National League Central Division champion Cincinnati Reds on July 31 for pitchers C.J. Nitkowski and minor-leaguer Dave Tuttle. Wells had been the only bright light on a miserable Tigers pitching staff; he had a 10-3 record with a 3.04 ERA when he left Detroit, and had even pitched a third of an inning in the All-Star Game.

After he stopped pinching himself at being traded to a contender, Wells joined the Reds’ rotation for the stretch run having won his last eight decisions in a row. Before his first start, against the New York Mets on August 2, Wells met with his new boss, the infamous team owner Marge Schott, who gave him some unusual encouragement.

“Reds owner Marge Schott, with her dog in tow, sought out Wells in the dugout a few minutes before the game and had an animated conversation,” the newspapers reported the next day. “Schott, who is picking up the remainder of Wells’ $2 million salary, patted the pitcher’s belly, squeezed his elbow and waved goodbye.”12 The pep talk worked because he pitched 7⅓ innings in a 6-2 Reds victory for his ninth consecutive win.

Wells was 6-5 with Cincinnati, giving him a 16-8 record for the season, with a 3.24 ERA as Cincinnati won the NL Central division title. In his first-ever postseason start, he helped the Reds clinch the Division Series with a 10-1 win to sweep the Dodgers. In Game Three of the NLCS against the Atlanta Braves, he gave up three earned runs in six innings of a 5-2 loss. Atlanta swept Cincinnati in four straight and went on to defeat Cleveland in the World Series.

While she may have enjoyed rubbing Wells’s belly, the notoriously parsimonious Schott did not want to pay the $3 million he was due for 1996 and so the Reds traded him to Baltimore for center fielder Curtis Goodwin and minor leaguer Trovin Valdez. The trade reunited Wells with Pat Gillick, his general manager in Toronto, who now held the same position with the Orioles.

Health issues hounded Wells in the spring and early in the season. He was hospitalized with a rapid heartbeat during spring training, but was released after an overnight stay. He also missed time in May with gout, returning on May 20, his birthday. His teammates welcomed him back and acknowledged his birthday by scoring 13 runs to give him his first win in five starts since April 16.

“It’s a nice gift, all those runs, but you still have to go out there and do the job,” Wells said. “Still, it’s a great advantage when you get that type of run support.”13

The win was a high point in an otherwise mediocre season for Wells, as he went 11-14 with a 5.14 ERA. Nonetheless, the Orioles’ 88-74 record was good enough to get them the wild-card playoff spot. Wells made a huge postseason contribution. He won Game One of the ALDS against the powerhouse Cleveland Indians and went seven frames in the clincher as Baltimore won in 12 innings to pull off the upset. He also earned the only Orioles victory in the ALCS as they lost to the Yankees in five games.

Just as Victor Kiam liked Remington Razors so much that he bought the company, the Yankees went out and signed Wells, the only pitcher to beat them in the ALCS, to a three-year, $13.5 million contract on December 24, 1996. The Yankees may have regretted their decision just three weeks later when he broke his pitching hand in a fight on January 14, 1997, while he was in San Diego attending his mother’s funeral. Wells ruffled the Yankees corporate feathers again when he said that he would like to wear Babe Ruth’s number 3, which the Yankees had retired in 1948.

“I asked for 03 and they wouldn’t do that,” said the longtime admirer of the Sultan of Swat. I’m hoping Mr. (Charlie) Hayes will give up No. 33.14 That way, I can be Babe Ruth twice over.”15

The number issue was less serious than Wells’s injury problems when spring training began. While he was still recovering from his broken hand, he had a recurrence of the gout that had bothered him the previous season. But for all the issues and headlines, Wells did produce. He went 16-10 with a 4.21 ERA and helped the Yankees win the American League wild-card playoff spot with a 96-66 record. The Yankees lost to Cleveland in the ALDS, but Wells pitched a 6-1 five-hitter at Jacobs Field to win Game Three, his only start.

Wells arrived at spring training for the 1998 season just three months shy of his 35th birthday. He strained a rib muscle early on and didn’t get his first spring-training start until March 14. He proceeded to have a season for the ages, going 18-4 with a 3.49 ERA, followed by a 4-0 run in the playoffs – he was chosen MVP in the ALCS – as the Yankees won the World Series. Wells also started the All-Star Game, and just for fun, he gave himself an early birthday present by pitching a perfect game at Yankee Stadium against the Minnesota Twins on May 17. It was the first perfect game in Yankee Stadium since fellow Point Loma alumnus Don Larsen performed the feat against the Brooklyn Dodgers in Game Five of the 1956 World Series.

The circumstances surrounding his perfecto would be difficult to believe if it involved anybody but Wells. Manager Joe Torre had pulled him from a May 6 start against Texas after he gave up seven earned runs in 2⅔ innings. Torre complained that Wells was out of shape and the two, along with pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre, had a long discussion about the situation. Judging by what he wrote in his autobiography, Wells was hardly in game shape when he showed up to face Minnesota.

“In his 2003 autobiography Perfect, I’m Not, Wells conceded that he pitched his gem ‘half-drunk, with bloodshot eyes, monster breath, and a raging, skull-rattling hangover,’ having gone to bed at 5 a.m. and gotten just an hour of sleep,” wrote Jay Jaffe in Sports Illustrated.16

In the Broadway musical Damn Yankees, the character Lola sings a song with the line, “Whatever Lola wants, Lola gets.” George Steinbrenner, owner of the damn Yankees, was like Lola because he also got whatever he wanted, and after the 1998 season, he wanted Blue Jays pitcher Roger Clemens for his team, and to get him, the Yankees traded Wells back to Toronto, along with pitcher Graeme Lloyd and second baseman Homer Bush. Wells was not pleased at going back to Toronto, but Jays general manager Ash assured him that he would be treated differently this time around.

“We did everything we could to control Boomer,” Ash said, referring to Wells’s first stint with Toronto. “We learned the hard way: The worst way to control him is to try and control him.”17

Hard way or not, the lesson was well learned. Boomer was allowed to be Boomer, heavy-metal music blaring in the locker room and all, and the result was the first of two marvelous seasons. Maybe he was partying like it was 1999, since it was, because he got off to a slow start and by the end of May was 5-5 with a stratospheric 6.30 ERA. Nonetheless, the Jays inked Wells to a one-year, $11.5 million contract extension on June 20, which spurred him on to a 17-10 record with an improved 4.82 ERA; he also led the league with seven complete games.

Cue the Twilight Zone music at this point, because it was in the year 2000 that Wells decided to have the only 20-win season of his career when he went 20-8, with a 4.11 ERA and a league-leading nine complete games. He also started the All-Star Game – his former manager Joe Torre selected him for the honor – as the Jays were in the pennant race for the whole season before finishing with an 83-79 record, 4½ games behind the eventual world champion Yankees.

Although the Blue Jays were willing to allow Wells to be himself, they felt enough was enough in early January, 2001, when Wells accused the Blue Jays organization of not doing enough to win and said that Toronto fans were “terrible.”18 They traded him to the Chicago White Sox for four players who ended up playing a total of 65 games for Toronto. From the standpoint of number of games played, it actually turned out to be an even trade. Wells went 5-7 with a 4.47 ERA, and didn’t pitch after June 28 because of back spasms. He ended up having season-ending surgery.

Just as with a great Broadway play, Wells had a New York revival when he signed for a second stint with the Yankees in 2002, because Steinbrenner wanted the now-39-year-old back in the fold. “David Wells is a winner and he belongs in pinstripes,” said Steinbrenner in a statement. “People say we’re going out on a limb, but we’ll see. We’re betting on The Boomer.”19

It turned out to be a good bet because Steinbrenner, a breeder, knew good horseflesh. Wells not only recovered from his back injury, he won six of his first seven decisions, and went on to have a 19-7 record, leading the rotation in both victories and winning percentage (.731) as the Yankees won the American League East with a 103-58 record. The usually clutch Wells couldn’t carry that regular season success into the playoffs as he got pounded in his lone start against the eventual World Series champion Anaheim Angels, who touched him for eight earned runs in 4⅔ innings in Game Four of the ALDS.

Wells was hot again in 2003, perhaps because of the hot water he found himself in prior to the season when his autobiography came out. Besides his description of his condition the day of his perfect game, he also said that a number of players were taking steroids. The resulting controversy was a pain in the Yankee brass and they fined him $100,000.

That little fracas aside, Wells was doing it again on the mound at age 40, going 15-7 with a 4.14 ERA as the Yankees went back to the World Series after a one-year drought. He defeated the Twins, 8-1, in the ALDS and Boston, 4-2, in the ALCS, but the World Series against the Florida Marlins was another matter. Wells lost Game One, 3-2, and had to leave Game Five due to tightness in his back after pitching a perfect first inning in a game the Yankees lost, 6-4.

Wells’s run in the Bronx ended after New York lost the World Series, so he decided to go home, and signed as a free agent with the Padres. At first it looked as though he couldn’t go home again, as he lost his first two starts, went on the disabled list due to a cut on his wrist, and by June 18 was 2-5. But damned if the old coot didn’t go 10-3 the rest of the way to finish 12-8, with a not-too-shabby 3.73 ERA.

The 2004 Red Sox called themselves “idiots” for their distinctive and often offbeat personalities, so perhaps it was no surprise that they signed Wells for the 2005 season. After all, he only had to replace three-time Cy Young Award winner Pedro Martinez, who won 16 games in 2004. Wells had the wags shaking their heads again as he went 15-7 in his summer of being 42, with a 4.45 ERA that was actually below the team ERA of 4.74. The Red Sox made the playoffs again as the wild card, but even Wells couldn’t prevent them from being swept by the eventual world champion Chicago White Sox. He gave up five runs, but only two earned, in 6⅔ innings of Game Two, which the White Sox won 5-4.

Age started creeping up on Wells in 2006, as he went a combined 3-5 with the Red Sox and Padres. He had one last shot in the playoffs with San Diego, and didn’t pitch badly in his only start in the ALDS, giving up two runs in five innings in Game Two to the St. Louis Cardinals, but that was all the Redbirds needed for a 2-0 win as they went on to win it all. Wells had a last hurrah, of sorts, in 2007; he had a 5-8 record with a 5.54 ERA when the Padres released him on August 13. But the Los Angeles Dodgers picked him up 11 days later, and he went 4-1 with them, albeit with a 5.12 ERA. He called it a career at age 44 after the season.

Wells was able to retire financially secure after earning more than $58 million playing baseball. He returned to San Diego to live with his wife, Nina, a former runway model whom he married in 2000, and their two sons, Brandon Miles and Lars Van. He got very active in community and charitable causes, raising money for diabetes research (he was diagnosed with the disease in 2007) and helped push through a school bond to pay for major upgrades to his high school’s baseball field, which now bears his name. As of 2015, he was the coach of the school’s team.

“If you can give back,” he said in a 2014 interview, “it’s a home run.”20

Last revised: November 4, 2017

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author used the following:

Abca.org.

Bluebirdbanter.com.

Hardballtimes.com.

Herald-Zeitung (New Braunfels, Texas).

Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette.

Kokomo (Indiana) Tribune.

Mlbreports.com.

New York Times.

Philly.com.

Plhsalumni.org.

Razon, Max. Born Under a Bad Sign (Bloomington, Indiana: Xlibris, 2009).

Salina (Kansas) Journal.

usatoday.com

Special thanks to Tom Larwin and the members of the Ted Williams SABR chapter for their assistance.

1 Accounts differ on the amounts. The higher numbers appear in a 1997 Sports Illustrated article, but Wells gave the lower numbers during a 2014 interview on the YES Network.

2 Franz Lidz, “The Unvarnished Ruth Free-Spirited Lefthander David Wells May Get Tattooed By Hitters Every Now And Then, But He’s Fulfilling His Dream – Pitching For The Yankees, The Team Of His Idol, The Babe,” Sports Illustrated, September 8, 1997.

3 Ibid.

4 YESnetwork.com interview.

5 “Cardinals talking with Horner,” Index-Journal (Greenwood, South Carolina), January 8, 1988.

6 Donaghy’s article appeared in the July 10, 1988, edition of the Altoona Mirror.

7 Mike DiGiovanna, “He Started a Reliever but Is Winning as a Starter,” Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1990.

8 In baseball, a swingman is a pitcher who works as both a starter and reliever.

9 Wells went only four innings in the loss to Boston because of a 58-minute rain delay. Pat Hentgen replaced him in the fifth.

10 Steve Milton, “Toronto Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1992: 46.

11 Jeff Pearlman, “Heavy Duty They said he wouldn’t last, but Toronto’s large-livin’ lefthander, David Wells, has become baseball’s most reliable pitcher – and a clubhouse wise man to boot,” Sports Illustrated, July 10, 2000.

12 “Los Angeles Tops Colorado,” News Record (North Hills, Pennsylvania), August 3, 1995.

13 “Orioles celebrate Wells’ birthday, 13-1,” Gettysburg Times, May 21, 1996.

14 Hayes, a Yankees teammate, gave Wells the number, and wore number 13 for the 1997 season.

15 “Wells has Ruthian request,” The Capital (Annapolis, Maryland), February 11, 1997.

16 Jay Jaffe, “15 years ago today: David Wells’ perfect game,” Sports Illustrated, May 17, 2013. Wells later said he was misquoted.

17 Jaffe.

18 Rick Gano, “Blue Jays trade Wells to White Sox,” Daily Journal (Ukiah, California), January 15, 2001.

19 “Slimmer Wells returns to Yankee Stadium,” Santa Cruz (California) Sentinel January 11, 2002.

20 Andrea Naversen, “At Home With David & Nina Wells,” Ranch & Coast, May 12, 2014.

Full Name

David Lee Wells

Born

May 20, 1963 at Torrance, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.