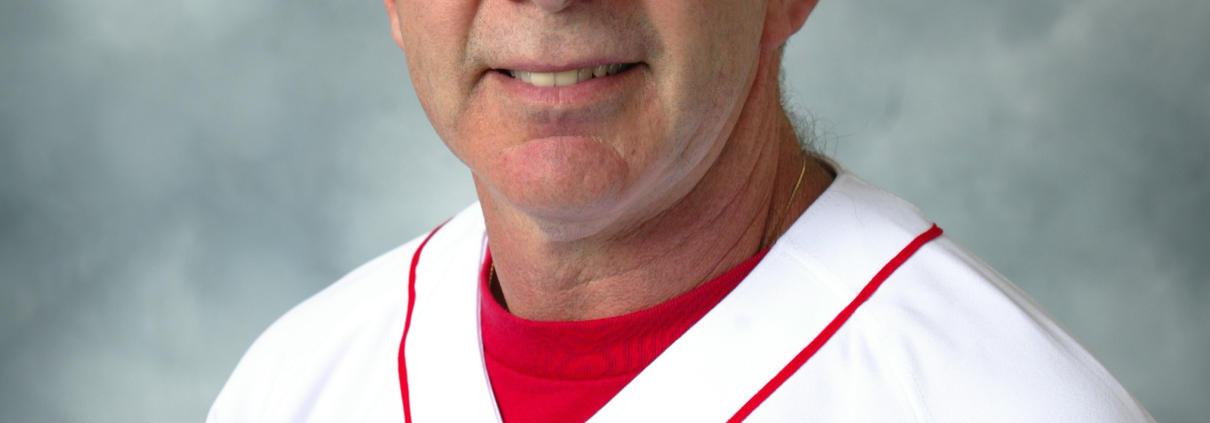

Dave Wallace

On June 9, 2003 with pitching coach Tony Cloninger taking a leave of absence to fight cancer, the Boston Red Sox named former Mets and Dodgers  pitching coach Dave Wallace to fill the void. 1 For Wallace, a Connecticut native with over three decades of professional baseball experience, it was not only a chance to go home to New England, but he was joining a team that was then sitting at 35-26, a half-game ahead of the New York Yankees in the American League East. But with that standing based far more on the club’s offensive production than on its pitching, Wallace was taking on no small challenge. Despite boasting multiple Cy Young Award winner Pedro Martínez as its ace, the staff that Wallace inherited had a team earned-run average of 5.26, the second worst in the American League. Less than 18 months later, with the interim tag removed, Wallace had helped transform the staff into one whose ERA in 2004, his first full season with the club, was not only third-best in the American League, but which, led by Martínez and Curt Schilling, made history as the Red Sox won the 2004 World Series, the team’s first title since 1918.

pitching coach Dave Wallace to fill the void. 1 For Wallace, a Connecticut native with over three decades of professional baseball experience, it was not only a chance to go home to New England, but he was joining a team that was then sitting at 35-26, a half-game ahead of the New York Yankees in the American League East. But with that standing based far more on the club’s offensive production than on its pitching, Wallace was taking on no small challenge. Despite boasting multiple Cy Young Award winner Pedro Martínez as its ace, the staff that Wallace inherited had a team earned-run average of 5.26, the second worst in the American League. Less than 18 months later, with the interim tag removed, Wallace had helped transform the staff into one whose ERA in 2004, his first full season with the club, was not only third-best in the American League, but which, led by Martínez and Curt Schilling, made history as the Red Sox won the 2004 World Series, the team’s first title since 1918.

It was the high point in Wallace’s baseball career, one that added a special sheen to his other accomplishments, but it was by no means an isolated achievement. Indeed, over the course of just under 50 years in professional baseball, Dave Wallace established himself as one of the most accomplished and respected pitching coaches and baseball men in the game. It was no accident that in 2012 Bleacher Report included him on a list of baseball’s top 50 all-time pitching coaches. 2

David William Wallace was born on September 7, 1947, in Waterbury, Connecticut. He grew up in the city about equidistant – 2 hours and 15 minutes in either direction – from New York City and Boston, and he starred in football, basketball, and baseball at Waterbury’s Sacred Heart High School. 3 Focusing on his real passion, he played baseball at the University of New Haven. There the 5-foot-10 right-handed pitcher compiled a record of 24-7 with a 2.18 earned-run average and 311 strikeouts over his four-year career, one that saw him lead the team into the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) national tournament in 1966 and earned him induction into the university’s Hall of Fame in 2000. 4 After graduating, the undrafted Wallace signed as a free agent with the Philadelphia Phillies in the fall of 1969.

Wallace began his professional career with the Spartanburg Phillies in the Class-A Western Carolina League in the summer of 1970. There he went 8-8 with a 5.16 ERA in 24 games, all starts. He threw seven complete games and pitched 150 innings.

The 1971 season saw Wallace improve those numbers significantly. Moved to the bullpen, and pitching for the Peninsula Phillies in the advanced Class-A Carolina League, he lowered his ERA to 1.24. He compiled a record of 6-1 while giving up only 30 hits in 58 innings. That performance earned him a promotion to the Triple-A Pacific Coast League Eugene Emeralds. Wallace was called upon for an occasional spot start, but 41 of his 47 appearances for Eugene were in relief as he went 8-5 with an ERA of 4.55. He started the 1973 season back in Eugene but after 43 appearances was sent down to the Reading Phillies in the Double-A Eastern League. There he shined, boasting a 1.59 ERA in 11 relief appearances and earning a call-up to the Phillies.

Wallace made his major-league debut on July 18, 1973, against the Cincinnati Reds at Cincinnati. Two months shy of his 26th birthday, he began the bottom of the eighth inning, relieving future Hall of Famer Steve Carlton, who had given up five runs in his seven innings of work. For Wallace it was something of a baptism by fire: Three of the first four batters he faced were future Hall of Famers. Wallace walked Joe Morgan to start the inning and then gave up a run-scoring double to Dave Concepción. That was followed by a single by Johnny Bench that put runners at first and third. Wallace then struck out Tony Pérez. However, the relief was only temporary as Wallace next gave up a double to Andy Kosco, which drove in Concepción. With the score now 7-0, Bucky Brandon replaced Wallace, who exited his debut with an ERA of 54.00. 5 Wallace made three more appearance with the Phillies that season, totaling 3⅔ innings while giving up 13 hits for an ERA of 22.09.

While he appeared in three games with the Phillies in 1974 and six with the Toronto Blue Jays in 1978, from 1974 through the end of 1979, Wallace spent most of his time in the minors, playing for the Toledo Mud Hens, the Oklahoma City 89ers, the Syracuse Chiefs, and finally the Pawtucket Red Sox. He retired as a player after the 1979 season never having earned a major-league win; his major-league record was 0-1 with an ERA of 7.84 in 13 appearances and 20⅔ innings pitched. Not auspicious numbers to be sure, but the lessons Wallace learned and his ability to impart them to younger pitchers would make for an impressive second career in professional baseball.

After a year away from professional baseball, in 1981 Wallace returned to the game, joining the Los Angeles Dodgers organization. For two seasons he coached for the Vero Beach Dodgers. From there he moved to the San Antonio Dodgers for the 1983 campaign before doing a three-season stint with the Albuquerque Dukes from 1984 to 1986. He was the organization’s minor-league pitching coordinator from 1987 to 1994, then the Dodgers’ pitching coach from 1995 to 1997. Over the course of his time in the Dodger organization he played a role in the development of a number of great pitchers, including most prominently Pedro Martínez and Orel Hershiser.

In 1999 Wallace switched gears, joining the New York Mets, for whom he was the pitching coach for two seasons, 1999 and 2000. During his time in New York, Wallace helped the Mets reach the NL Championship Series in 1999 and the World Series in 2000, with strong pitching being central to their success – the 1999 team was fifth in the league in ERA while the 2000 team was third. Despite the success, Wallace and Mets manager Bobby Valentine never developed a close relationship and Wallace opted to return to the Dodgers after the 2000 season. 6 There he worked as a special assistant to the general manager before assuming the role of interim general manager for the 2001 season and had the title of senior vice president for baseball operations in 2002. In the latter role he oversaw the team’s minor-league operations and was a consultant to Dodgers GM Dan Evans.

Wallace’s hiring by the Red Sox in 2003 was not a total surprise, for while the move to replace Cloninger came in midseason, the Red Sox had long coveted him, contacting the Dodgers during the previous offseason about the possibility of Wallace’s moving east. While it was just an inquiry, the Dodgers made clear that they valued Wallace, telling the Red Sox that they would want compensation if such a move occurred. Of course, given that he had spent 20 years spread out over two different stints with the Dodgers, it was not a surprise that they were reluctant to see him go. At the same time, the prospect of going to the Red Sox represented something of a homecoming for the Connecticut native. When Cloninger was forced to go on indefinite medical leave, the Red Sox became more aggressive in their pursuit of Wallace, with a member of the Red Sox ownership contacting Dodgers chair Bob Daly seeking permission to talk with the pitching guru, an inquiry not the norm for a pitching-coach candidate. And yet while the Dodgers relented, and Wallace joined the team in June, many expected that his coaching days would be limited with a return to the front office a likely future move. In fact, Wallace was attracted to the idea of returning to the field and to working directly with players as well as returning to New England, where he had grown up, and while he was initially an “interim” when he began in June, he expected to be there for the long haul. 7

And so it was that while Cloninger successfully beat the cancer and subsequently remained with the Red Sox for almost 15 years as a player development consultant, Wallace quickly made the post his own, while setting out to gain the trust of a struggling rotation, one that behind ace Martínez included starters Derek Lowe, Tim Wakefield, and John Burkett, with closer Byung-Hyun Kim and Mike Timlin and Alan Embree, anchoring the bullpen. The veteran coach had done his homework and he knew what they had to offer, but especially coming in midseason, Wallace said that nothing was more important than “building a bond with the players” and demonstrating that he was “sensitive to their needs.” 8 Wallace acknowledged that the whole process was made easier by his previous work with Martínez, who could attest to what his old coach had to offer. 9 The results of Wallace’s tutelage soon became apparent. As the season unfolded and under Wallace’s steady hand, the staff came together, showing substantive improvement. By season’s end, the team ERA had dropped to 4.48, which ranked eighth in the American League.

As the Red Sox headed into 2004, with the partial 2003 season having given Wallace a sense of what the pitching staff could do, the team was ready to take the final step toward its long-sought championship. The near-miss against the Yankees in the previous year’s American League Championship Series had led GM Theo Epstein to strengthen the pitching staff, securing the services of All-Star right-hander Curt Schilling as well as Bronson Arroyo. The team also acquired Keith Foulke to be the closer after Byung-Hyun Kim had struggled down the stretch in 2003, dogged by a series of injuries that that never allowed him to return to his peak form. Wallace was particularly pleased with the addition of Schilling and Foulke, a pair he believed did much to “firm up a solid rotation.” 10

This group under the new manager, Terry Francona, and with Wallace overseeing the staff from the start, helped the Red Sox win 98 games to finish second behind the Yankees. The pitching staff, featuring starters Schilling, and Martínez at the top, complemented by Derek Lowe, Tim Wakefield, and Bronson Arroyo, with Timlin and Embree handling most of the middle-inning work and Foulke the closer, continued the improvement that had occurred under Wallace in 2003, further lowering the staff’s ERA to 4.18, third-best in the American League.

The postseason was memorable and historic as the Red Sox made an unprecedented comeback, erasing the Yankees’ three-games-to-none lead in the League Championship Series to take the American League pennant, before sweeping the St. Louis Cardinals to win the franchise’s first World Series in 86 years. While heroes abounded, the honor roll certainly included Wallace’s pitching staff, especially Schilling, Martínez, Lowe, and Foulke.

Wallace has called the season the “peak” of his career, saying that “words can’t describe the satisfaction” he felt as the team came back against the Yankees before ultimately winning the World Series. 11 He remembers the team fondly, saying it was “quite a conglomerate of personalities.” 12 It was, he recalled, an extraordinary experience as the team methodically put together the comeback for the ages. As “crazy” as the team was, Wallace remembered their focus. Down three games to none, they knew they had to win one game at a time. And to do that, he remembered, they determined to take it one step at a time, focusing on “winning the at-bat,” “winning the situation,” and ultimately winning the game en route to mounting a comeback for the ages. 13 The team’s determination was mixed with a toughness embodied in Schilling’s “Bloody Sock” game, an effort that did not surprise Wallace, who had no doubts about the hard-throwing right-hander making the start. 14

While the Red Sox again finished second to the Yankees in 2005, Wallace faced many new crises on a pitching staff that had been so important to the success of the 2004 World Series team. Pedro Martínez and Derek Lowe signed as free agents with the New York Mets and Los Angeles Dodgers respectively, and Curt Schilling suffered a series of injuries that limited the right-handed workhorse to fewer than 100 innings pitched. 15 That left only Tim Wakefield and Bronson Arroyo from the championship starting staff, and while the middle relievers and closer remained, Wallace had to work hard to put together a staff that could compete. Ultimately the Red Sox lost to the White Sox in the American League Division Series, ending their quest for a repeat championship.

The 2006 season was a nightmare for Wallace. Driving to spring training in February, he was in South Carolina when he experienced a searing pain in his hip, which had been previously replaced. He called the team doctor, who told him to drive to the nearest hospital. Unable to continue, Wallace was picked up by an ambulance at the side of the road in Spartanburg, South Carolina. 16 He went into septic shock caused by salmonella attacking the artificial hip. He spent three days in intensive care before he was transferred to a hospital in Massachusetts. Released after three weeks in the hospital, he was forced to return after two days. The artificial hip was removed and replaced and Wallace was on crutches for just short of six months. 17 He returned to the Red Sox by midsummer but the team had essentially moved on and he resigned at the end of the season.

But Wallace was not ready to leave the game, and although weak and with his weight down to 150, 35 pounds under his playing weight, he accepted an offer to join the Houston Astros as their pitching coach. 18 It did not turn out well, and at the end of the 2007 season, Wallace headed back to the West Coast, accepting a job as special assistant to the Mariners’ executive VP, pitching development. At the end of the 2008 season he was named the team’s minor-league pitching coordinator.

Wallace returned to the East the following year, joining the Atlanta Braves, for whom he was the minor-league pitching coordinator from 2010 to 2013. That stint was interrupted briefly in 2011 when he filled in for Braves pitching coach Roger McDowell who was placed on administrative leave while the team investigated allegations of homophobic slurs and threatening behavior. However, after 2013, differences between Wallace and the front office led to a parting of the ways.

From Atlanta Wallace moved north and back to the American League, becoming the pitching coach for the Baltimore Orioles. In three seasons working with manager Buck Showalter, he helped with a team renaissance. During that time the Orioles won the AL East in 2014 while winning 96 games as well as securing the wild-card spot in 2016. It was to Wallace’s credit that despite the fact that the Orioles had no true ace, they were still able to finish with the third-best ERA in the American League in 2014. Things did not get any easier in the next two years. In fact, in 2016, the Orioles had only a single starter who won more than 10 games on a staff that saw 27 pitchers make at least one appearance. It was challenging, to be sure.

In the aftermath of the 2016 season, the Orioles announced that Wallace had decided to retire as the team’s pitching coach after his three-year stint. According to Baltimore manager Showalter, Wallace hoped to stay involved with the game as a part-time pitching instructor in the major leagues, but at the time of the announcement he had no definite plan. 19 Not long afterward, he returned to the Braves, signing on as a pitching consultant. It was seen as a more passive role for the then 69-year-old Wallace, and was ultimately one he filled for three years until February 2020, when it was announced that he and the team had mutually agree to part ways, a move likely resulting from some substantive changes in the way the new front-office leadership sought to proceed. 20

Wallace’s departure from the Braves appeared to mark the end of his professional career, one that dated back to his first season of minor-league ball in the Phillies organization. And yet while he sat out the COVID pandemic of 2020, in April of 2021 Wallace was named the pitching coach for the United States national baseball team, which at that point still needed to participate in a final qualifying tournament to earn a spot in the delayed 2020 Olympics taking place in Tokyo at summer’s end. 21 Led by former Angels manager Mike Scioscia, the team qualified for the trip to Tokyo and with Wallace continuing as pitching coach for the Olympics, the US earned a Silver Medal, falling to the home-team Japanese in the championship game in a 2-0 pitchers’ duel. 22

In many ways, the Olympic assignment was an appropriate end to the second half of Dave Wallace’s career. His time with Red Sox had marked a return to dealing directly with players, particularly pitchers, and it was an experience he realized brought him his greatest satisfaction. Likening what he did to being a teacher, in looking back, he said he realized that it was that interaction with the players that he really enjoyed and found the most rewarding. Working with a mix of players, each with their different backgrounds and cultures, Wallace relished “the chance to have an impact on their lives.” That, he said, was what really appealed to him. He said the Olympics and the chance to represent their country brought out another side to the players, one he observed again during the 2023 World Baseball Classic. 23

In the aftermath of the Olympics, Wallace returned to Waterbury, where he was honored by his former hometown, which gave him the key to the city. Expressing his surprise and appreciation at the turnout, Wallace called Waterbury a “baseball crazy town” and the place where he had gotten the foundation for the almost half-century-long career that had culminated in the Olympic Silver Medal-winning effort. 24

While he had expected the Olympics to be his last assignment, as spring training 2023 approached, an old friend, Miami Marlins general manager Kim Ng signed Wallace as a consultant, a post that allowed him to bring his years of experience to the young Marlins staff, one headed by 2022 Cy Young Award winner Sandy Alcantara. Wallace said it was an ideal assignment, another one that allowed him to work and mentor young hurlers in the Marlins organization, traveling periodically to different sites during the season from his summer home in the Boston area. 25

Wallace has been married to the former Joyce Shellman since January 4, 1997. 26 The couple split their time between Florida in the winter and the Boston area during the baseball season. 27

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-almanac.com and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Jimmy Golen, “Red Sox Tab Wallace to Replace Ailing Cloninger,” New Bedford (Massachusetts) Standard Times, June 10, 2003; https://www.southcoasttoday.com/story/sports/2003/06/10/red-sox-tab-wallace-to/50392644007/.

2 Doug Mead, “The 50 Best MLB Pitching Coaches of All Time,” Bleacher Report, February 1, 2012; https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1047146-the-50-best-mlb-pitching-coaches-of-all-time.

3 David W. Wallace, 1947, Bronson Library; http://www.bronsonlibrary.org/filestorage/1521/1545/HOF_2014_Wallace_David_W.pdf.

4 “Dave Wallace,” University of New Haven Athletic Hall of Fame; https://newhavenchargers.com/honors/hall-of-fame/dave-wallace/92.

5 Matt Veasey, “Phillies 50: Forgotten 1973 – Ron Diorio and Dave Wallace,” July 18, 2020; https://mattveasey.com/2020/07/18/philadelphia-phillies-50-forgotten-1973-ron-diorio-and-dave-wallace/.

6 “Dave Wallace Stats,” Baseball Almanac; Dave Wallace: 2000 N.L. Champion Mets Pitching Coach (1998-2000),” centerfieldmaz, September 06, 2022; http://www.centerfieldmaz.com/2018/09/2000-nl-champion-mets-pitching-coach.html.

7 Dave Wallace, telephone interview, February 27, 2023.

8 Wallace interview, February 27, 2023.

9 Dave Wallace, telephone interview, April 13, 2023.

10 Wallace interview, February 27, 2023.

11 Wallace interview, April 13, 2023.

12 Wallace interview, April 13, 2023.

13 Wallace interview, February 27, 2023.

14 Wallace interview, February 27, 2023.

15 “2005 Boston Red Sox Statistics,” Baseball Reference; https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/BOS/2005.shtml.

16 Tyler Kepner, “A Mentor Whose Experience Goes Far Beyond Pitching,” New York Times, September 22, 2014.

17 Kepner.

18 Kepner.

19 “Former Red Sox Coach Dave Wallace Retiring,” Boston25 News, October 6, 2016; https://www.boston25news.com/sports/former-red-sox-coach-dave-wallace-retiring/454309756/.

20 “Braves, Dave Wallace Mutually Part Ways,” ATL, Atlanta Sports Talk, February 28, 2020; https://www.sportstalkatl.com/braves-dave-wallace-mutually-part-ways/.

21 “Former Orioles Pitching Coach Dave Wallace to Be Mike Scioscia’s Olympic Pitching Coach,” Baltimore Sun, April 23, 2021; https://www.baltimoresun.com/sports/orioles/bs-sp-dave-wallace-olympic-pitching-coach-20210423-v4c5uyyxuvg3nop2alf4qdik4e-story.html.

22 “Team USA Brings Home Silver From Olympic Games Tokyo 2020,” USA Baseball, August 7, 2021; https://www.usabaseball.com/news/topic/general/team-usa-brings-home-silver-from-olympic-games-tokyo-2020.

23 Wallace interview, April 13, 2023.

24 “Waterbury Walkabout: Former Baseball Pro Receives Keys to the City,” Waterbury Republican American, September 25, 2021; https://archives.rep-am.com/2021/09/25/waterbury-walkabout-former-baseball-pro-receives-keys-to-the-city/.

25 Wallace interview, February 27, 2023.

26 “Dave Wallace,” IMDb; https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1991613/bio.

27 Wallace interview, February 27, 2023.

Full Name

David William Wallace

Born

September 7, 1947 at Waterbury, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.