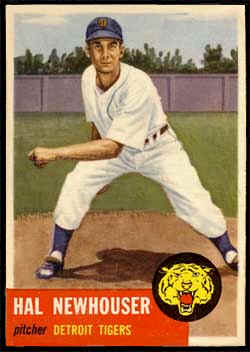

Hal Newhouser

“Prince Hal” Newhouser had the unique distinction of being baseball’s best pitcher during the 1940s — as well as its most unpopular player. An uncompromising perfectionist who was as hard on himself as his teammates, he was famous for his hot left arm and mercurial temperament. Whether Newhouser was mowing down enemy hitters or smashing a case of Coke bottles against the clubhouse wall, he was given a wide berth by opponents and teammates alike. Hal began his baseball career as a gangly, wide-eyed teenager and finished as one of the smartest scouts in the game. In between he made a few friends and plenty of enemies, left a lifetime of memories for baseball fans in Detroit, and was part of the Indians’ lights-out bullpen during their historic 1954 campaign.

“Prince Hal” Newhouser had the unique distinction of being baseball’s best pitcher during the 1940s — as well as its most unpopular player. An uncompromising perfectionist who was as hard on himself as his teammates, he was famous for his hot left arm and mercurial temperament. Whether Newhouser was mowing down enemy hitters or smashing a case of Coke bottles against the clubhouse wall, he was given a wide berth by opponents and teammates alike. Hal began his baseball career as a gangly, wide-eyed teenager and finished as one of the smartest scouts in the game. In between he made a few friends and plenty of enemies, left a lifetime of memories for baseball fans in Detroit, and was part of the Indians’ lights-out bullpen during their historic 1954 campaign.

Harold Newhouser was born on May 20, 1921, in Detroit, Michigan. His parents were first-generation immigrants. His father, Theodore, was a draftsman in the automotive industry. He had been a gymnast in his native Czechoslovakia. His mother was Austrian. Newhouser got his athleticism from his father and his serious (some would say sour) disposition from his mother.

The Newhousers had moved to Detroit from Pittsburgh before Hal was born. Although there was good, steady work during the Great Depression, the family still struggled to make ends meet. Despite the fact that Hal and his four-years-older brother, Dick, were exceptional athletes, the Newhousers showed little interest in sports other than gymnastics. Even after Dick was signed to a contract by the Tigers and played a couple of seasons of minor-league ball, his parents didn’t know much about baseball and didn’t care. Dick left the game in his second year after he was beaned and suffered a fractured skull.

The scout who signed Dick was Wish Egan, a man who sought to corner the local market on baseball talent. Through Dick, Egan got the inside track on Hal, a skinny left-hander who could whip a baseball with tremendous force, and who already seemed to have the grim, competitive makeup of a pro pitcher as he entered his teen years. Hal was deadly serious at all times. Teammates and sportswriters later noted that he had no sense of humor.

Hal Newhouser was a true survivor. He took every manner of odd job, including selling papers, setting pins in a bowling alley, and collecting empty bottles for the penny deposits. During the winter he would wander over to the coalyard and collect discarded flakes in a gunnysack to take home. When the mercury plummeted, every little bit helped – especially if it was free.

As a boy Newhouser also survived several serious injuries. He punctured his stomach when he fell off a woodpile onto a metal spike. He received a nasty head injury when another boy hit him with a brick. During a basketball game he got a bad floor burn and then obsessively picked at the scab until he got blood poisoning. He got several deep gashes playing football, too. A deep scar under his right eye became more noticeable as he grew older. By the time he was in the majors, he could look downright scary.

When Newhouser was 14, he listened to the radio as Goose Goslin drove Mickey Cochrane home with the winning run in the 1935 World Series. He decided that day that he wanted to pitch for the hometown Tigers. Newhouser was already playing softball in a fast-pitch league, pitching and playing first base. Bob Ladie, who coached a top sandlot team in Detroit, suggested that he try throwing a baseball. Young Hal took the mound for the first time at 15. Over the next three seasons he won 42 games and lost only three times.

Newhouser developed an explosive but hard-to-control fastball and good overhand curve. He also gained a reputation as a perfectionist with an explosive temper. He expected the best from himself as well as his teammates. When his fielders booted a ball, when his hitters failed to give him the runs he needed, he took it very personally. He was a difficult teammate to say the least; later, during his heyday with Detroit, he was characterized as the most unpopular man in the locker room.

But ballplayers will put up with a lot if you win, and win he did. At Egan’s suggestion, he quit the baseball team at Wilbur Wright Trade School and pitched American Legion ball instead. His fellow students at Wright signed a petition asking him to reconsider but he had his sights set on a bigger prize. Against this higher grade of competition, Newhouser was simply fantastic. During one stretch he won 19 games in a row and pitched 65 scoreless innings, striking out 20 or more hitters five times. Also at Egan’s insistence, he quit the school basketball team – after being captain for two seasons – so he could focus on baseball.

The Tigers decided to sign 17-year-old Hal in the summer of 1938, right after he returned from the American Legion tournament. But by then the secret was out and other teams – most notably the Indians – were hovering. Wish Egan had the inside track and he used it to close the deal on the evening of August 6. Egan got the boy’s signature on a contract and paid him a $500 bonus in $100 bills. Hal gave $400 to mom and dad, and socked away $100 for himself in case he didn’t make it as a pro. Plan B was to go to an industrial school to study tool and die work.

A little while after Newhouser signed the contract, he was walking down the street when the Indians’ head scout, Cy Slapnicka, pulled up in a shiny new car. He offered Newhouser a $15,000 bonus and the car. Hal was crushed. Slapnicka had been late because he was picking up the car!

At virtually the same time, the Tigers were engineering the departure of manager Mickey Cochrane, replacing him with Del Baker. When Egan – who had known Iron Mike since he arrived Detroit – heard the news he was unmoved. “A couple of years from now the Tigers will win pennants no matter who manages them,” he told his secretary. “Today I’ve just signed the greatest left-handed pitcher I ever saw.”1

Newhouser reported for duty the following spring to the Tigers’ minor-league club in Alexandria, Louisiana. He dominated batters at two minor-league stops that summer, first in the Evangeline League with Alexandria and then with Beaumont of the Texas League. He logged a total of 230 innings on his teenage arm. Later Newhouser felt that had he been brought along more slowly, he would not have experienced the arm and shoulder problems that began plaguing him in his late 20s.

Newhouser won his first game as a pro, striking out 18 batters, and then seven more before earning a promotion to Beaumont. He won his first four games with his new team before Texas League batters figured they could wait him out and force him to groove his pitches when he was behind in the count. Newhouser lost 13 in a row at one point and the Tigers were getting alarming reports about the 18-year-old’s temper. Egan stepped in at this point and suggested that he join Detroit, mostly so they could keep an eye on him.

Newhouser joined a team led by pitchers Schoolboy Rowe, Tommy Bridges, and Bobo Newsom. He was part of a youth movement that included Dizzy Trout and fellow teenager Fred Hutchinson. It was manager Del Baker’s plan to work the youngsters into the rotation and phase out Roxie Lawson, Vern Kennedy, and George Gill – all whom had been traded away by the time Newhouser reached the majors.

Newhouser appeared in one game in 1939. On September 29 he started, giving up three hits and four walks in five innings in the second game of a doubleheader against the Indians. The game was called on account of darkness, and Newhouser took the loss. It was one of 73 suffered by the Tigers that year against 81 victories. Detroit obviously had superb pitching, but the Bengals’ offense was in flux. Hank Greenberg and Rudy York supplied ample power, while veteran Charlie Gehringer was a perennial .300 hitter. The rest of the lineup was good but not great, peppered with the likes of Birdie Tebbetts, Barney McCosky, Pinky Higgins, and Pete Fox.

Which made what happened in 1940 all the more remarkable. Baker needed York’s bat in the lineup every day. A catcher by trade, York did not offer the receiving skills of Tebbetts and thus had functioned primarily as a backup player and pinch-hitter. Baker moved Greenberg to left field and stationed York at first base. York exploded with a 33-homer, 134-RBI season, while Greenberg held his own in left and came within a dozen points of winning the Triple Crown.

The veterans on the Tigers pitching staff took full advantage of this firepower, with Newsom, Bridges, and Rowe combining for a 49-17 record. Newhouser was in the rotation most of the year, making 20 starts and going 9-9 with a 4.86 earned-run average. Every outing was an adventure. When he threw the fastball for strikes and located his curve, he was tough to beat. When his control was off, it was painful to watch him. These swings were not always game to game. Sometimes they were inning to inning.

As a 19-year-old in thick of a pennant race, “Prince Hal” was not always in control of his emotions. In his wilder moments, he would pace around the mound, trying to regain his composure, worried what the veterans were thinking. Often he would peer into the stands, searching for the large hat worn by his mother, who sat along the right-field line when she attended games at Briggs Stadium. His father never saw him pitch at Tiger Stadium – he was working during the afternoons and the Tigers were a noted holdout where night baseball was concerned. Later, Newhouser bought his folks a house in Asbury Park, New Jersey, where they opened a small pattern-making business.

After being pulled from a game by Baker, Newhouser was like a hurricane (his alternate nickname was Hurricane Hal). He would throw tantrums in the clubhouse that reminded baseball people of another volatile southpaw, Lefty Grove. Once he destroyed an entire case of Coke, smashing each bottle against the locker-room wall. Over the years Newhouser would become so irate that he demanded that the Tigers trade him. After cooling off, he would always come to his senses.

Even in calmer times, Newhouser could be tough to take. As tradition dictated, the Tigers had Newhouser room with Rowe, the veteran who had grown up in the Detroit system. All Newhouser wanted to talk about was the minutiae of pitching. He drove Rowe crazy.

Every one of those nine wins in 1940 turned out to be precious. The Tigers and Indians battled all summer, while the juggernaut Yankees – a last-place team in May – came around and made a spirited dash for first place in September. The smart money was on the Indians until a player revolt against manager Ossie Vitt destabilized the clubhouse. In the end Detroit survived to win the pennant by a game over Cleveland and two over New York.

The World Series against the Reds was a tight affair that went the full seven games. Newhouser did not see the light of day, and watched from the dugout as Cincinnati took the final two games by scores of 4-0 and 2-1.

The law of gravity caught up with the Tigers and Indians in 1941, as both teams tumbled into a fourth-place tie with sub-.500 records. Missing from the lineup was Greenberg, one of the first ballplayers drafted in advance of the Second World War. That left York as the club’s sole power source and not surprisingly his numbers declined.

Once again Newhouser was part of the Detroit rotation, this time going 9-11 with a 4.79 ERA. It was essentially a repeat of the previous season. He ran hot and cold, fanning hitters when he got ahead in the count, and getting knocked all over the park when he fell behind. On the upside, Hal, 20, married his girl, Beryl, in 1941. They had met at a party a couple of years earlier.

On December 5 Detroit fans got good news when the military announced that it was discharging all men over the age of 28. They had exactly two days to rejoice about the return of Hammering Hank before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor plunged America into war.

Newhouser’s wartime plans involved being sworn into the Army Air Force on the mound at Briggs Stadium. However, he failed his physical after doctors heard the swoosh of a mitral-valve prolapse. He was classified 4-F, unfit for duty. Newhouser tried on other occasions to slip through the medical screening as Greenberg had (originally, he too was 4-F due to bad feet) but the stethoscope told doctors all they needed to know, and Hal was excused from service.

Newhouser made the best of his situation, pitching well enough against the league’s dwindling offensive talent in 1942 to make his first All-Star Game. No one suspected it at the time, but this would be the first of six straight All-Star selections. Newhouser was not easy to score on, as witnessed by his 2.45 ERA. But the Tigers lineup had been decimated by the draft and struggled mightily to generate runs. The result was an 8-14 record for Newhouser. He completed 11 games and also functioned as the team’s closer at times, racking up five saves. The Tigers finished below .500 again, in fifth place.

Newhouser’s control was the big issue. More often than not it was horrible. In 1943 former catcher Steve O’Neill replaced Baker as manager and brought in Paul Richards to handle the young staff. Richards, who was already establishing himself as a baseball guru, would be charged with squeezing the long-awaited potential out of Newhouser and his teammates.

The new manager and catcher were exasperated by the number of walks Newhouser issued in 1943 – a league-high 111 in just over 195 innings. He worked his way in and out of trouble constantly, running up big pitch counts and getting pulled for pinch-hitters in the middle innings, which drove him crazy. His moodiness and frustration grew even worse. At season’s end Newhouser’s record was a dismal 8-17. Had the war not been taking a heavy toll on major-league rosters, Newhouser probably would have been farmed out, released, or traded.

As Newhouser headed into the 1944 season, he had to make an important career decision. He was 34-52 at this point, and a source of great frustration to his teammates and Tigers management. His father had secured an offseason job for him as an apprentice draftsman at Chrysler headquarters and he showed enough promise to be offered a full-time job with a very attractive salary. He agreed that it was a good opportunity, but informed his parents that he would give baseball one more shot.

Newhouser sensed that O’Neill and Richards had much to teach him. Trout and Virgil Trucks, another product of the Tigers’ farm system, had made the transition to effective major-league starters. Detroit, whose pitching was getting thinner and thinner, really needed Hal to “grow up” and join them atop the rotation.

When Newhouser arrived at the wartime spring-training camp in Indiana, Richards told him that he was a thrower. “I’m going to make you a pitcher,” he said.2 By this time Newhouser was a three-pitch pitcher, with a fastball, curveball, and changeup. Richards taught him how to throw a slider. Back then the pitch was known somewhat derogatorily as a nickel curve, but in Newhouser’s hand it was a sharp-breaking pitch that looked enough like his fastball that batters couldn’t handle it.

Another part of the transformation involved teaching Newhouser to harness his emotions. Whatever Richards said and did worked miracles. Newhouser became a completely different pitcher, on the mound and in the clubhouse. Meanwhile, Richards managed to turn Trout into a top pitcher, too.

Newhouser led the Tigers into battle during one of the weirdest seasons in AL history. Two second-division clubs, the Boston Red Sox and St. Louis Browns, joined the Tigers and Yankees in a wild four-team race that lasted well into September. Boston faded after losing key players to the Army, but the Browns and Yankees kept pace. The only reason New York didn’t run away with the race was Newhouser. He beat them six times that season.

The Browns shocked the Yankees in a late-season series to put them out of the running, and with two days left Detroit and St. Louis sported identical 87-65 records. Newhouser won his start – victory number 29, which led the majors – but the Browns won, too. Trout, whose season was every bit as good as Newhouser’s, took the mound on the final day and lost to the Senators. In St. Louis the Browns scored a comeback win over the Yankees to nail down the pennant.

After the season, the MVP vote was a toss-up between Newhouser and Trout. Dizzy had 27 victories to Newhouser’s 29, but had made 40 starts, logged 352⅓ innings and had an ERA of 2.12. Trout actually received more first-place votes than Newhouser, but Hal won the overall voting by four points to cop the trophy by a narrow margin. Newhouser had led the majors with 187 strikeouts, and had an ERA of 2.22. He twirled six shutouts to Trout’s seven, and also saved two wins for Detroit, thus he had a hand in a total of 31 victories.

While Trout was never as good again, Newhouser continued his assault on American League batters. In 1945 he led the AL with 313 innings pitched, 29 complete games, 212 strikeouts, eight shutouts, and a 1.81 ERA. He won 25 times and lost nine, with a couple of saves on top. Rarely has a pitcher gone through a season with the total command Newhouser enjoyed. His strikeout total seems tame by modern standards, but at the time the second-place finisher, Nels Potter of the Browns, had 83 fewer.

The Tigers welcomed Hank Greenberg back at midseason and also reacquired outfielder Roy Cullenbine in a trade with the Indians early in the year. Cullenbine established himself as the team’s table-setter, while Greenberg got into 78 games and regained his swing in time for another thrilling four-way pennant race.

Hal may have alienated his teammates at times, but they knew he was a gamer. Toward the end of 1945, his back began spasming and the team decided that he should stay in Detroit while the Tigers made their final Eastern trip. When they arrived in New York, general manager Jack Zeller revisited this decision and phoned Newhouser to ask him to fly to New York. The Tigers pitchers were exhausted and the thinking was that Newhouser might be able to fool the Yankees for a couple of innings before they realized he wasn’t himself. Newhouser threw a curve to Charlie Keller and practically passed out from the pain, so he stuck with a fastball and changeup. Newhouser ended up blanking the Yankees on four hits that afternoon.

The Tigers rolled into Washington in late September with a half-game lead on the surprising Senators and plenty of bumps and bruises. Eddie Mayo had a sore shoulder. Greenberg was limping on a sprained ankle. And Newhouser’s back was killing him. He lasted only one inning before leaving the first game of a crucial twin bill. The Tigers rallied to win 7-4 and took the nightcap 7-3 behind Trout, who won his fifth game in two weeks. They split the next day’s doubleheader.

The Senators finished their schedule the following week with 87 wins, a game behind the Tigers. Detroit, however, was unable to clinch because of four consecutive rainouts. The weather finally cleared with the Tigers needing one win to clinch and avoid a playoff with the Senators. Virgil Trucks, who missed the entire year in the Navy, was released in time to start the final game for Detroit. He allowed one run over five-plus innings, but got into trouble in the sixth. Newhouser came in from the bullpen and wriggled out of a one-out, bases-loaded jam to preserve a 2-1 lead. The pesky Browns scored single runs off Newhouser in the seventh and eighth to take a 3-2 lead. In the ninth inning the Tigers loaded the bases and Greenberg hit his most famous home run, a shot into the left-field stands that won the game for Newhouser and the pennant for Detroit. Newhouser ended up leading the majors in wins, strikeouts, and ERA, pitching’s version of the Triple Crown. This time Newhouser was a central character in the World Series. The Tigers opened the Series against the Chicago Cubs in Detroit with Hal on the mound. He got absolutely clobbered in a 9-0 rout, giving up seven runs before being yanked in the third inning. The Tigers had played terrible defense behind Newhouser, but he blamed himself for this one. He had not made good pitches when he needed to.

The series seesawed back and forth and was tied at two games apiece when Newhouser redeemed himself in Game Five with an 8-4 complete-game victory. Hal was called upon three days later to start Game Seven. The Tigers staked him to five runs in the top of the first inning – highlighted by a bases-clearing double by his catcher, Paul Richards – and Newhouser kept Chicago under control for nine innings, scattering ten hits and striking out ten for an easy 9-3 victory. With the exception of the Game One debacle, Newhouser just blew the Cubs away in the series. In 20⅔ innings he fanned 22 batters and walked only four.

After the Series, Newhouser was named the league MVP again. In doing so he became the first – and still the only – hurler to win back-to-back Most Valuable Player awards. Newhouser later admitted that he tried hard to win the second award. He knew how tough it was for a pitcher to win it, and was determined to win it twice.

The winter of 1945-46 brought some interesting developments in the baseball world. Jorge Pasquel decided to take advantage of all the returning baseball talent and transform his Mexican League into a major league. The key was luring a few big names south of the border. There was no bigger name in baseball than Prince Hal Newhouser. Pasquel offered him $200,000 to pitch for three seasons, with a $300,000 signing bonus.

For a player who had missed a big payday once, this seemed too good to pass up. Newhouser felt a lot of loyalty to the Tigers, and informed owner Walter Briggs that he was being wooed by Pasquel. The Tigers gave him a $10,000 bonus to stay with the club, with a promise of much more after the season, when his new contract came due. Worried that he might be banned from baseball if the Mexican League imploded, Newhouser took the Detroit offer and never looked back. The Tigers did give him a big raise, to more than $60,000 a year.

The 1946 season belonged to the Red Sox, who celebrated the return from military duty of Ted Williams by winning 104 games and running away from the league. The Tigers finished second, 12 games out. Newhouser was again the top pitcher in the AL, winning a league-best 26 games and taking the ERA crown again with a 1.94 mark. Any doubts that the returning stars would expose him as an inferior pitcher were erased by his stellar season. Although Williams won the MVP award, Newhouser finished close on his heels in second place.

The Tigers had a wonderful starting staff in 1946. Trout, Trucks, and Fred Hutchinson combined to go 45-33 and rarely gave up more than three runs a game. Meanwhile, Greenberg was the top power hitter in the league, and the team had just acquired George Kell, a future batting champion, at the suggestion of Hal’s old mentor, Wish Egan. They also had Dick Wakefield, one of the brightest young stars in baseball. Detroit fans had plenty to look forward to.

After the 1946 season the Tigers chatted to the Yankees about pitching. New York had failed to win a pennant for a fourth straight year and the Tigers were loaded. Hal’s name came up in conversation and so did Joe DiMaggio’s. Was a trade of these two stars specifically discussed? Rumors that it did have circulated ever since.

The 1947 Tigers finished in second place, 12 games out, for the second year in a row. This time they were looking up at the Yankees. The missing piece to their puzzle was Greenberg, who had gotten into a fight with management over his salary and abruptly retired. The Tigers sold his contract to the Pirates, where he played one final season. Meanwhile, the Detroit offense became a black hole. No Tiger hit 25 homers or knocked in or scored 100 runs. Kell was the only regular over .300.

With little offensive support, Newhouser’s record dropped to 17-17. He still had a tremendous season, completing 24 of his 36 starts, fanning 176 batters and turning in an ERA of 2.87. Though he had been a big leaguer for nearly a decade, he still had moments of teen-like frustration. During a game at Briggs Stadium in August, O’Neill attempted to remove Newhouser in the third inning after he gave up five runs to the Red Sox. Hal insisted he had his good stuff and simply refused to leave the mound. O’Neill later fined him $250 for his obstinacy – the first fine he had doled out as Tigers manager. It was also the first time Newhouser had actually ever been fined, despite having done untold damage to clubhouses around the league.

If anyone was qualified to judge his own stuff, it was Newhouser. Long before teams used videotape and analyzed pitching motions, Hal had film shot of his games through an expensive lens. He would run the movies at home between starts looking for flaws in his motion and also in his grip. Toward the end of his frustrating 1947 campaign, he purchased a second projector and ran films side by side on two screens. One film showed him during his big years of the mid-1940s. The other had his most recent starts. After hours of study he noticed a slight difference in his follow-through. He corrected the flaw and won three of his final four decisions. He later discovered that he had been playing with a broken right foot.

The Tigers faded from the first division in 1948, finishing a respectable 78-76 but in fifth place. The offense was the problem again. This time they were without Kell for a long stretch of the summer, and rising stars Hoot Evers and Vic Wertz weren’t ready to carry the club. For his part, Newhouser had another stellar season. He led the AL with 21 wins and, with 143 strikeouts, was top man on a Detroit staff that finished first in K’s. A decade’s worth of innings had taken the edge off Newhouser’s fastball, but he still got it to the plate in the 90s and had become quite adept at locating his big curve.

On June 15 the Tigers became the last American League team to install lights. Owner Briggs was a staunch proponent of day baseball and even after the first night game he told reporters he did not envision the club playing too many of them. Newhouser was on the mound to deliver the first pitch against the Philadelphia A’s at 9:30 P.M. He allowed two hits in a 4-1 victory, later ranking this night among his top baseball thrills. More than 50,000 people were in the stands, and the team received a long, loud ovation after the final out. It was one of the few bright spots in a season that saw Detroit finish 18½ games out of first place.

Newhouser did figure in the 1948 pennant race. On the season’s final day, he faced Bob Feller. These were always exciting matchups, and although Feller typically got the best of the Tigers when they faced each other, Newhouser did have one of his most memorable moments on this particular occasion. Newhouser’s shoulder was aching and he was throwing on one day’s rest, but he pitched one of the best games of his life, winning 7-1 in front of a deflated crowd at Municipal Stadium. The victory prevented the Tribe from clinching the pennant, and forced them into a one-game playoff with the Red Sox, which they won. Newhouser’s 21st victory put him one ahead of both Bob Lemon and Gene Bearden, Rapid Robert’s teammates.

The 1948 season was Newhouser’s last as a 20-game winner. The shoulder pain he felt that day never really went away. Over the years doctors and trainers tried everything they could to diagnose and relieve the pain. By Newhouser’s own estimate he was x-rayed more than 100 times during his career. He had shots in his neck, a tooth pulled, and every type of chiropractic maneuver in the book.

Newhouser labored through the 1949 campaign, winning 18 times often on sheer guile. Red Rolfe, the old Yankee star, was now the manager. He squeezed decent years out of fellow veterans Trucks and Hutchinson, and got 25 wins from young starters Art Houtteman and Ted Gray. The Tigers got big years out of Wertz and Kell to finish 20 games over .500, in fourth place.

Detroit continued its winning ways in 1950. The Tigers battled the Yankees, Red Sox, and Indians all year, but finished in second place three games behind the pennant-winning New Yorkers. Newhouser went 15-13 but could no longer count on his fastball to get him out of trouble. His ERA soared to 4.34.

From their fine showing in 1950 the Tigers tumbled into the second division the following year. Newhouser spent half the season unable to pitch because of shoulder woes, going 6-6 in 14 starts. The smooth, rhythmic movement that had characterized his delivery was gone. For a player so concerned with form, it was sheer torture. Newhouser didn’t win a game after the All-Star break and was unable to make any starts after mid-July. During the year he was offered a job with a Detroit company for $30,000 a year but turned it down without revealing the firm’s name. He wanted to keep pitching.

Newhouser also wanted to keep working with kids. He was a fountain of information on his craft and actually wrote a book entitled Pitching to Win. He also had established a kids club in Detroit and a few other cities called Hal’s Pals. He met with members on offdays and before games when he wasn’t pitching. He also collected used equipment and sent it to the different clubs after the season. Through these interactions he developed a taste for scouting, no doubt spurred by the memory of Wish Egan. Hal had been a pallbearer at Egan’s funeral in April of 1951.

The Tigers cut Newhouser’s salary by the maximum 25 percent for 1952, but he refused to sign the contract GM Charlie Gehringer sent him until he was sure he could pitch without pain. He went to Lakeland, Florida, at his own expense a month early and began working out. While some ballplayers would have cringed at the thought of extra work in the spring, Newhouser was a great believer in intense training. Forty laps around the park were just a warm-up for him.

When Newhouser was confident he could make it through the season he made a fascinating proposal to the team. He was due $31,000 for 1952. Instead he asked for a five-year deal for $100,000. If for some reason he could not pitch, the salary would cover him as a minor-league pitching instructor or major-league coach. The Tigers had a longstanding rule against multiyear contracts. After careful consideration they turned him down.

Newhouser managed to make 19 starts in 1952 but was only marginally effective. He went 9-9 with a 3.74 ERA, and toward the end of the year lost his starting spot to young Billy Hoeft. Newhouser’s final victory of the season was also his 200th. It turned out to be his last as a Tiger. The following season he made it into only seven games. He was 0–1 with a 7.06 ERA for Detroit.

Newhouser was released by the Tigers before the 1954 season and decided it might be time to retire. His old teammate Hank Greenberg was GM and part owner of the Indians. Greenberg offered him a chance to unretire and make the club as a reliever. Newhouser took it. The move to the bullpen could not have been an easy one for Hal. He was nothing if not pragmatic, but he also was famous for not wanting to leave the mound. At times the ball had to be pried from his hand while he pleaded his case.

The signing turned out to be brilliant. Everything went right for Cleveland during the regular season. Newhouser pitched primarily in long relief, winning seven games and saving seven others against just two losses. His ERA was a neat 2.51. Newhouser was part of a lights-out bullpen that featured a pair of 25-year-old call-ups, Don Mossi and Ray Narleski. Between this threesome they accounted for 16 wins and saved 27 of the Tribe’s record 111 victories that season. (Saves were not an official statistic at that time, and the 27 were compiled in later years.) The Giants shocked the Indians in the World Series, scoring a four-game sweep. Newhouser saw action in Game Four. He relieved Lemon in the fifth inning but failed to retire the two batters he faced.

With his final seven victories, Newhouser moved ahead of two Rubes – Marquard and Waddell – into eighth place all-time on the list of victories by left-handers. Hal made just two appearances in 1955 before he was released. His final numbers were 207 wins and 150 losses with a career ERA of 3.06. Newhouser led the American League in wins four times in five seasons and in strikeouts, complete games, and ERA twice. He also was the top man in shutouts one season.

Hal Newhouser stayed in baseball, scouting for many years in Michigan – not a job for the faint-hearted, given the state’s April temperatures. He worked for the Orioles, Indians, Tigers, and Astros in the four decades after his retirement as a player. His first discovery was Milt Pappas in 1957. He spotted the righthander at Cooley High in Detroit and connected him with the Orioles. Pappas would make the big club after just a handful of minor-league starts and star as one of the Baby Birds for Newhouser’s old catcher, Paul Richards. A couple of years later, Newhouser signed Dean Chance for the O’s. Chance later won a Cy Young Award with the Angels.

Newhouser’s last employer was the Houston Astros. He quit after the Astros overrode his suggestion to make Derek Jeter the first pick in the 1992 draft. Houston took Phil Nevin instead. Newhouser had watched Jeter play many times and got to know his family – the kid was a lock, he told his wife, Beryl, even at the $1 million bonus many thought it would take to lure the shortstop away from the University of Michigan. “No one is worth a million dollars,” Hal told his boss, Dan O’Brien, “but if one kid is worth that, it’s this kid.”3

Over the years Newhouser suffered the indignity of being passed over by Hall of Fame voters not for his lack of talent, but for the talent drain in baseball during the years in which he excelled. He was what baseball people disdainfully referred to as a Wartime Pitcher. They conveniently ignored the fact that in the postwar years 1946 to 1950, he averaged just under 20 wins a season. In his last year of eligibility he received 155 votes, his best showing by far but still far short of what he needed.

As the years passed Newhouser became more philosophical about this slight. He half-understood what the voters were going through – even those on the Veterans Committee who had tried to hit against him. For several years he listened to the radio on the day the Hall of Fame enshrinees were announced, but after too many years of not hearing his name, Hal stopped listening.

After more than three decades of eligibility, Newhouser finally got the call from Cooperstown in 1992. He cried when he heard the news – not because he had made it, but because his mother, 92, was still alive to see her son receive his just rewards.

Newhouser was the first Detroit-born Tiger to reach Cooperstown. He went into the Hall of Fame with pitchers Tom Seaver and Rollie Fingers and Bill McGowan, the late umpire. Among those passed over by the Veterans Committee that year were Phil Rizzuto, Nellie Fox, Earl Weaver, Joe Gordon, Leo Durocher, and Vic Willis – all of whom would later make it – and Gil Hodges, who as of 2019 was still waiting.

A few years later Newhouser began suffering from emphysema and heart problems, but lived to see his number 16 retired by the Tigers. He died on November 10, 1998, at Providence Hospital in Southfield, near his home in Bloomfield Hills. He was survived by Beryl and his daughters, Charlene and Cherrill, as well as his brother, Richard.

The story around baseball during Newhouser’s MVP years was that he learned to control his temper the day he learned to control his fastball. Sometimes it was the other way around. Soon it became baseball lore. Hal was nothing if not honest, and always made a point of refuting this theory.

“That’s nonsense,” he liked to say. “I’ll be hot-headed all my life. That’s just the kind of guy I am.” I didn’t win because I controlled my temper,” he was quick to add. “I controlled my temper because I began to win. … There’s no use getting mad when you’re winning!”4

Sources

Books and Guides

Richard Goldstein, Spartan Seasons (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1980)

Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001)

David Jordan, A Tiger in His Time (Dallas: Taylor Publishing, 1990)

Tom Meany, Baseball’s Greatest Pitchers (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1951)

David Neft, Richard Goldstein, and Michael Neft, The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball (New York: St. Martin’s, 2007)

Hal Newhouser, Pitching to Win (Chicago: Ziff-Davis Publishing Co., 1948)

Mike Shatzkin and Jim Charlton, The Ballplayers (New York: Arbor House, 1990)

Baseball Research Journal (Larry Amman)

The Sporting News Baseball Guide

The Sporting News Baseball Register

Magazines

Larry Amman, “Newhouser and Trout in 1944: 56 Wins and a Near Miss,” SABR’s Baseball Research Journal, Volume 12, 1983

Notes

1 Quote attributed to Wish Egan, source unknown.

2 “Transformation to Pitcher,” New York Times, June 11, 1989.

3 Buster Olney, “The Pride of Kalamazoo,” New York Times, April 4, 1999.

4 Milton Gross, “The Truth About Newhouser,” Sport, August 1948.

Full Name

Harold Newhouser

Born

May 20, 1921 at Detroit, MI (USA)

Died

November 10, 1998 at Southfield, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.