July 11, 1944: NL’s Cavarretta shines in wartime All-Star Game

The twelfth All-Star Game saw the National League prevail for only the fourth time. Often second cousins to the American League in the early going, they wouldn’t win again until 1950.

Only 29,589 fans, about four thousand below the capacity of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, came to the nine o’clock night game, the second consecutive nighttime affair in All-Star Game history.[fn]Vincent et al, The Midsummer Classic: The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game, 62; See also “This Day In Baseball, July 13, 1943.”[/fn] Despite the disappointing crowd, the game successfully supported ongoing World War II fundraising efforts. The Army and Navy’s Bat and Ball Fund received the game receipts of $81,275, and another $25,000 came from the Gillette Safety Razor Company for radio rights. Baseball concessionaire Sportservice made a donation. Everybody, including sportswriters and club officials, paid full admission, doubled for the wartime All-Star Games.[fn]Vincent et al, 68.[/fn]

Only 29,589 fans, about four thousand below the capacity of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, came to the nine o’clock night game, the second consecutive nighttime affair in All-Star Game history.[fn]Vincent et al, The Midsummer Classic: The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game, 62; See also “This Day In Baseball, July 13, 1943.”[/fn] Despite the disappointing crowd, the game successfully supported ongoing World War II fundraising efforts. The Army and Navy’s Bat and Ball Fund received the game receipts of $81,275, and another $25,000 came from the Gillette Safety Razor Company for radio rights. Baseball concessionaire Sportservice made a donation. Everybody, including sportswriters and club officials, paid full admission, doubled for the wartime All-Star Games.[fn]Vincent et al, 68.[/fn]

The lopsided 7-1 score aside, the game was fairly mundane and play was less than spectacular, as several journeyman “just glad to be here” players made their only All-Star Game appearances. There were no home runs — that hadn’t happened for six years, when the National League won in Cincinnati. American Leaguers Bobby Doerr, Frankie Hayes, and George McQuinn each committed an error, as did Connie Ryan for the Nationals.

Losing pitcher Tex Hughson (Red Sox) and Detroit’s eventual 1944 American League MVP Hal Newhouser had some trouble, but otherwise the pitching for both sides was solid. Ken Raffensberger (Phillies) got the win in two innings of work. The win was some consolation for Raffensberger, who went on to lead the National League with 20 losses for the season. Pirate pitcher Rip Sewell worked the sixth, seventh, and eighth innings, striking out two and walking one while holding the AL hitless and showing off his notorious “eephus” or blooper pitch.

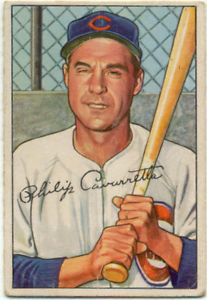

The player of the game, had there been such an award, would almost certainly have been the Cubs’ Phil Cavarretta, who became the first to reach base five times in an All-Star Game, on a triple, a single, and three walks. Thrown out twice at home plate, however, he scored only one of the NL’s runs.

Despite the war, the game had some star power, with 10 future members of the Hall of Fame: Doerr, Newhouser, Lou Boudreau, and Rick Ferrell for the American League; Stan Musial, Mel Ott, and Joe Medwick for the National League; umpire Cal Hubbard; and managers Joe McCarthy and Billy Southworth. All the players except Boudreau and Ferrell appeared in the game.

Overall, the National League had bigger names, with seven past, present, and future MVP winners: Medwick, Bucky Walters, Frank McCormick, Musial, Marty Marion, Cavarretta, and Bob Elliott.

The 1944 All-Star Game stands out for what it tells us about baseball during World War II. Rosters in both leagues were depleted as players enlisted or were drafted after Pearl Harbor. The players who stepped in for them were often too young or old, classified 4-F, and not as skilled or talented as those who were away, especially three and four years into the war. The July 6 Sporting News observed that 14 (actually 15 with Frankie Zak of the Pirates replacing injured Reds shortstop Eddie Miller) players were making their first appearance on All-Star rosters. This was, however, fewer than in 1943, when 18 men made their All-Star debuts.[fn]The Sporting News, July 6, 1944, 4.[/fn]

Some of the new All-Stars went on to solid careers that included other All-Star Game selections, Joe Page, Dizzy Trout, Cavarretta, and Red Munger among them. Others weren’t so fortunate. Jim Tobin and Raffensberger had relatively long careers but were stuck on weak teams. Hank Borowy was merely ordinary after the war. Pete Fox, a fine player who was 35 and had been around for a while, was just too old.

For a good many, though, the 1944 game was their only opportunity and an honor for keeping the game going through the war. In the years since they’ve been pretty much forgotten:

Orval Grove (White Sox) lasted until April 27, 1949, when, just 29, he pitched in his only game of the season for less than inning and left with an ERA of 54.00.

Oris Hockett (Indians) had been around since 1938. At 34 he finally became an All-Star, hitting .289. He had similar numbers in 1945, but he played his last game on September 7.

Bob Muncrief of the 1944 American League pennant-winning Browns was stuck on the number 13, winning 13 games in 1941, 1943, 1944, and 1945. After the war he had trouble beating anybody and finished up on April 20, 1951, albeit in Yankee pinstripes.

Bespectacled center fielder Thurman Tucker of White Sox hit .287 in his All-Star season. He was in the Navy in 1945, but returned to the Sox in 1946 to hit .288. He got into 83 games with the World Series champion Indians in 1948, and last played on April 29, 1951.

Braves right-hander Nate Andrews rebounded from a league-leading 20 losses in 1943 to go 16-15 in his All-Star season. His career ended in mid-1946.

Second baseman Don Johnson of the Cubs didn’t reach the majors until 1943, when he was 31 years old. He hung around the majors long enough to play in all seven games (hitting .172 in 33 plate appearances) in the World Series with the 1945 Cubs, but was demoted after six games in 1948 and never returned.

Ray Mueller of the Reds came up with Boston (NL) in 1935 and bounced around with several National League clubs. He had his best year in 1944, with 10 home runs and 73 RBIs to go along with a .286 average, all career highs. He caught all 155 of the Reds’ games in that All-Star season, justifiably earning the nickname “Iron Man.” He spent 1945 in the Army and caught 114 games in 1946. After that he was pretty much an every-other-day backstop, which kept him around through September 1951.

Connie Ryan played second and third base over 12 years with five different teams in both leagues. A lifetime .248 hitter, he took advantage of wartime pitching to hit .295 in 88 games for the Braves in 1944, entering the Navy later that year and serving in the Pacific through 1945. He came back to play until April 1954.

Ninety-Six, South Carolina, native Bill Voiselle (Giants) remains the only MLB player whose uniform number matched the name of his hometown. In his first full season in the majors, he led the National League with 161 strikeouts and tied for third with 21 wins. He did well to maintain a .500 record after 1944 and pitched his final game on July 8, 1950.

Even seventy years later, injury replacement (for the Reds’ Eddie Miller) Frankie Zak, a 22-year-old backup shortstop for the host Pirates, remains perhaps the oddest member of an All-Star club. Zak hadn’t left town for the All-Star break and was available, although he didn’t get into the game. He finished the 1944 season at an even .300, on mostly singles with only 11 RBIs in 186 trips to the plate. With the singles, though, his 22 walks to 18 strikeouts lifted him to a .385 on-base percentage. The epitome of the wartime player, Zak got into just 15 games in 1945 and 21 in 1946. He was gone after June 10 that year at age 24 and out of baseball at 27 after three years bouncing around Triple-A.

Wartime travel restrictions forced the cancellation of the 1945 All-Star Game, and by 1946, the “boys (Ted Williams, Bob Feller, Hank Greenberg, Joe and Dominic DiMaggio, Johnny Mize, Enos Slaughter, and many others) were back.” But baseball had served a vital purpose by persevering while they were away, and those first-and-only-time 1944 All-Stars had had their moments in the sun.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Jack Zerby for his invaluable editing of this article. He improved it beyond measure.

Sources

Allen, Thomas E. If They Hadn’t Gone: How World War II Affected Major League Baseball. Springfield: Southwest Missouri State University, 2004.

Anton, Todd, and Bill Nowlin, eds. When Baseball Went to War. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2008.

Coleman, Bruce Reaves. True Stars of the Major Leagues. Madison, Mississippi: Circuit Clout Press, Inc., 1998.

Honig, Donald. The All-Star Game: A Pictorial History, 1933 to Present. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1987.

Mead, William B. Even the Browns: Baseball During World War II. Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc., 1978; rept. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 2010.

Vincent, David, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith. The Midsummer Classic: The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

1944 All-Star Game program. Author’s collection.

The Sporting News, various issues, July 1943, July 1944, and July 1945.

“This Day In Baseball, July 13, 1943,” espnmlb.com (Accessed July 28, 2014).

Baseball-Almanac.com

BaseballInWartime.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Additional Stats

National League 7

American League 1

Forbes Field

Pittsburgh, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.