San Diego Breaks Pacific Coast League Color Barrier

This article was written by Alan Cohen

This article was published in The National Pastime: Pacific Ghosts (San Diego, 2019)

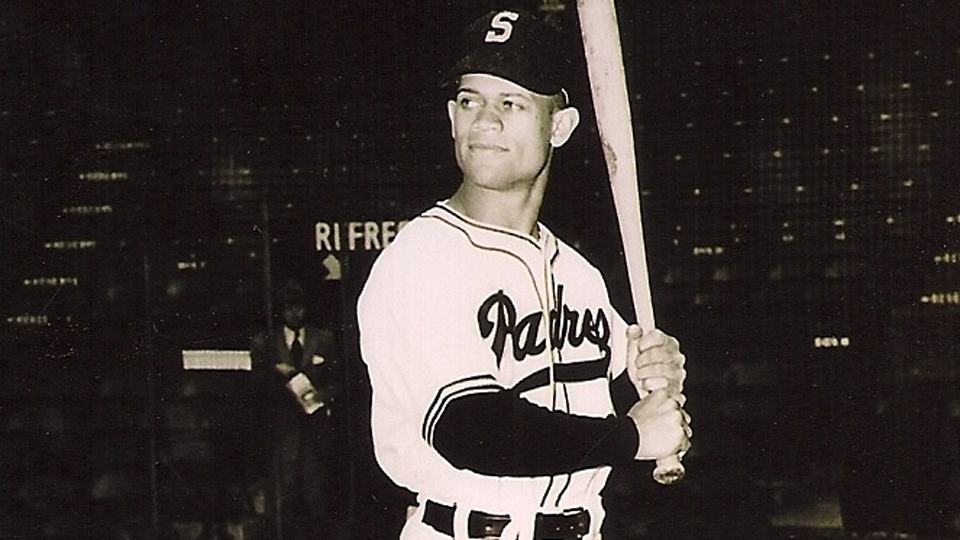

Johnny Ritchey broke the Pacific Coast League’s color barrier with the San Diego Padres in 1948. (COURTESY OF BILL SWANK)

On March 30, 2005, the Padres unveiled a bust of Johnny Ritchey at the recently opened Petco Park, two years after his death. On February 21, 2017, Ritchey was inducted into the Breitbard Hall of Fame in San Diego. Why was Ritchie memorialized so? He was the Pacific Coast League’s barrier breaker in terms of color.

The year after Jackie Robinson broke the major-league color barrier in 1947, the Cleveland Indians bought Minnie Miñoso from the New York Cubans of the Negro National League. Minoso, who had been an infielder with the Cubans, would be moved to the outfield when he joined the Indians at the beginning of the 1949 season. Minoso needed tutelage, which he received in San Diego after joining the Indians’ Triple-A affiliate in mid-May 1948. He and Luke Easter formed the nucleus of the Padres — who would advance to the Pacific Coast League playoffs for the first time since 1942 — but they were not the first black players with the Padres. On November 22, 1947, the Padres had signed San Diego’s Ritchey to a contract. Ritchey, a catcher, played in 103 games in 1948, batting .323. He spent parts of seven seasons in the Pacific Coast League but never got the call to play in the majors.

As a youngster in San Diego, Ritchey — who was born on January 5, 1923 — had starred in American Legion ball and was on teams that advanced far in tournaments in 1938 and 1940. In 1940, he was barred because of his color from participating in the championship game. As Wendell Smith noted in the Pittsburgh Courier, “The American Legion bowed to un-Americanism again last week by permitting the Legion of Albermarle, N.C., to bar San Diego’s two colored stars, Johnny Ritchey and Nelson Manuel. Playing down in Albermarle, N.C., the two colored kids were benched because the Southerners didn’t want to play against them. The San Diego Legion submitted to Albermarle’s demands.”1

After graduating from high school in 1941, Ritchey went to San Diego State College, but his college career was interrupted after one year by service in the Army during World War II. After the war, he returned to school and led his team in batting with a .356 average in 1946. He left San Diego State in 1947 and signed on with the Chicago American Giants of the Negro American League, with whom he had a great season. When his team completed the final game of the home season on September 14, Ritchey was sporting a .376 batting average, best in the Negro American League.2

Interest in his talents was shown by the Chicago Cubs, with whom he tried out September 19, but he elected to sign with Bill Starr, president of the Pacific Coast League’s San Diego Padres. At the time of the signing, Starr said, “We believe we have signed one of the finest prospects in the country. We are not sponsoring any causes. Our interest in Ritchey is primarily that he can swing that bat. He is a potential major league prospect and has a better than reasonable chance of helping the Padres.”3

It was anticipated that he would be sent down to the Padres’ Tacoma affiliate in the Western International League, but Ritchey stayed with San Diego. He officially broke the league’s color line when, appearing as a pinch-hitter on March 30, 1948, he grounded out in the first game of the PCL season.4 Then, due to injuries to catchers Len Rice in the first game and Hank Camelli in the second game, only Earl Kuper and Ritchey were available to catch. Kuper replaced Camelli in the second game, a 17–2 loss, and Ritchey got his first hit as a pinch-hitter in the same game. Ritchey’s first start was the following day. He tripled and singled in a 12–5 win. He went on a hitting spree and his numbers for the first five games of the season were remarkable. He went 7-for-11 with a double, a triple, and a homer. Although he was relegated to the bench when Rice and Camelli returned to action, Ritchey appeared in 103 of his team’s 188 games, and his .323 batting average was second best on the team.On Opening Day in 1949, the Padres had three black faces in the starting lineup. Johnny Ritchey was back for his second season with the team and he was joined by Luke Easter and Artie Wilson.

In 1949, when the Padres formalized their affiliation with Bill Veeck’s Cleveland Indians, they demolished the color line. The pipeline established, Veeck and his general manager, Hank Greenberg, would funnel player after player to San Diego for years. Some were destined for major-league stardom. Others would have a cup of coffee in the big leagues. Still others, often past their prime when they played with the Padres, would not get to the big leagues.

Luscious Easter, at age 33, came to the team after having played with the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League for two years. Prior to 1947, he had been somewhat under the radar, having a nomadic experience in Negro baseball dating back to 1937, when he began playing for a St. Louis team that spent much time barnstorming. In 1946, he had played with the independent Cincinnati Crescents. In 1948, when the Homestead Grays won the last Negro League World Series, Easter played in both East-West All-Star games.

Luscious Easter, at age 33, came to the team after having played with the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League for two years. Prior to 1947, he had been somewhat under the radar, having a nomadic experience in Negro baseball dating back to 1937, when he began playing for a St. Louis team that spent much time barnstorming. In 1946, he had played with the independent Cincinnati Crescents. In 1948, when the Homestead Grays won the last Negro League World Series, Easter played in both East-West All-Star games.

He didn’t last the whole season with the Padres. In early August, he was called up to the big leagues by the Indians after batting .363 with 25 homers and 92 RBIs in 80 games for San Diego. From 1950 through 1952, he slugged 86 homers and drove in 307 runs. In 1954, at age 38 he was sent back to San Diego by the Indians and banged out 13 homers in 56 games. His career was not over, not by a longshot. At age 40, he became the scourge of the International League, slugging 35 or more homers in three successive seasons with Buffalo. He struck his last homers with Rochester at age 47 in 1963 and retired after the 1964 season.

Early in 1949, Veeck had signed infielder Artie Wilson, who had been a headliner in the Negro Leagues, finishing second in the league in batting in 1945 with a .372 average as reported by the Pittsburgh Courier.5 Veeck also signed Easter around the same time, but little notice was paid to Luke until he batted .474 in March as the Padres prepped for the season.

Wilson was not with the Padres for long. The Yankees had disputed his signing by Veeck and gained rights to the shortstop. The Yankees sold Wilson to Oakland of the Pacific Coast League, where he became the first player of color with the Oaks, batting .350. His overall average for 1949, .348, put him atop the league’s batters. Wilson did not enjoy success in the majors. He played briefly for the New York Giants. His first game was on April 18, 1951. After playing in his 19th game on May 23, he was sent back to the minors when Willie Mays was called up to the Giants. Wilson also broke the color line with Seattle, for whom he played from 1952 through 1954, and with Portland in 1955.

After the 1949 season was underway, the Padres added Minoso to the lineup. He made it to the majors to stay in 1951, but after less than a month with the Indians, he was traded to the White Sox, with whom he spent most of his career. He was a nine-time American League All-Star, and in 10 of his first 11 full seasons in the majors, he led the league in being hit by pitches. In his first three full seasons, he led the league in stolen bases, and he was the triples leader three times. He could also hit the ball over the fence. He had 186 homers in the majors and had 20 or more in four seasons. When they got around to giving awards for defensive skills, he won three Gold Gloves.

After the 1949 season, Ritchey was traded to the Portland Beavers. Although often said to have major-league talent with the bat, his fielding was suspect, and he tended to throw the ball wildly. He never got the call to the big leagues.

On the mound in 1950 for the Padres was 36-year-old Roy Welmaker, who had been part of the great Homestead Grays teams from 1936 through 1945 and had played in the East-West All-Star game in 1945, pitching two shutout innings. He signed with Cleveland prior to the 1949 season and went 22–12 at Wilkes-Barre in the Class A Eastern League. In 1950 with San Diego, he was 16–10. Although he pitched in the PCL for three more seasons, Welmaker was well past his prime and didn’t make it to the majors.

The 1950 Padres finished four games behind the Oaks and had three black outfielders in the vanguard. Minoso, in his second year with the club, batted .339, fifth in the league, with 20 homers and 115 RBIs in 169 games.

The Indians had plucked Harry Simpson off the roster of the Cubans and he spent 1949 at Wilkes-Barre, leading the league in homers with 31. In 1950 with the Padres, Simpson put up even bigger power numbers than Minoso, with 33 homers and 156 RBIs in 178 games. The next season, Simpson, who played for five big-league teams over an eight-year span, earning the nickname “Suitcase,” was with the Indians.

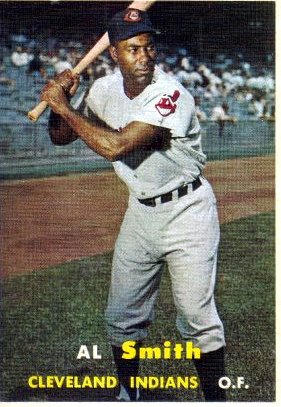

Completing the trio of great black outfielders on the 1950 Padres was Al Smith, who had played with the Cleveland Buckeyes in the Negro American League and was part of their Negro League World Series championship team in 1947. He was signed by the Indians on July 11, 1948, and spent the balance of that season and 1949 with Wilkes-Barre. After spending 1950 and ’51 with the Padres, he was sent to the new top Indians farm team, Indianapolis, in 1952. Midway through 1953, he joined Cleveland.

Completing the trio of great black outfielders on the 1950 Padres was Al Smith, who had played with the Cleveland Buckeyes in the Negro American League and was part of their Negro League World Series championship team in 1947. He was signed by the Indians on July 11, 1948, and spent the balance of that season and 1949 with Wilkes-Barre. After spending 1950 and ’51 with the Padres, he was sent to the new top Indians farm team, Indianapolis, in 1952. Midway through 1953, he joined Cleveland.

The connection with the Indians would send more players of color to the Padres in 1951. Sam Jones, who had spent the 1948 season with the Buckeyes, was signed by the Indians and spent the 1950 season with Wilkes-Barre. In 1951, he was with the Padres, going 16–13 with a league-leading 246 strikeouts. Jones had success at the major-league level. After brief trials with the Indians in 1951 and ’52, he moved on to the Cubs organization and was named to the National League All-Star team in 1955. In 1959 with the San Francisco Giants, he won 21 games and led the National League in shutouts (4) and ERA (2.83).

Pitcher Henry Miller was with the Padres for a short time in 1951. He was a noted Negro League player, but he only had a brief taste of Organized Baseball. Miller was 33 years old in 1951 and had spent 11 years with the Philadelphia Stars of the Negro National League. He only appeared in six games with the Padres.

Toward the end of the 1951 season, Jose Santiago joined the Padres. He had pitched for the New York Cubans as a teenager in 1947 and ’48 and joined the Indians organization prior to the 1949 season. After stops at Dayton and Wilkes-Barre, he joined the Padres, going an unspectacular 1–5. A baseball nomad, he had three trips to the big leagues playing with the Indians for parts of 1954 and ’55 and the Athletics for part of 1956.

The Indians temporarily suspended their affiliation with the Padres after 1951, but players of color would continue to be part of the team in the following years.

Theolic Smith came on board in 1952. When he started pitching professionally in 1936, he was part of the Pittsburgh Crawfords. the top team in the middle years of the Negro National League. He appeared in three Negro East-West games and hurled in the Mexican League before coming to the Padres at age 39.

Milt Smith and Tom Alston were also on the 1952 team. They were the first Padres of color without Negro League credentials.

Alston was in his second year of professional ball and joined the Padres midway through the season. He also spent the entire 1953 season with the Padres, batting .297 in 180 games. He played parts of four seasons with the St. Louis Cardinals after becoming, on April 13, 1954, the first player of color to play for the Cardinals.

Milt Smith joined the Padres late in 1952, coming to San Diego from Lewiston, Idaho, in the Western International League, where he had batted .318. In 1953, he once again began the season at a lower level, but once promoted to the Padres, he batted .271 in 55 games. He stayed with the Padres through 1955 and was batting .338 when the Cincinnati Reds brought him up to the majors. He played in 36 games for the Reds in 1955 and was the 61st player to break the twentieth-century major-league color barrier.

By this point, the PCL’s growing pains in terms of integration were over, and in 1952, three of the league’s top four batting averages were posted by persons of color. None of the three was with the Padres, but it was San Diego that had carved the path. In 1954, the Padres tied for first place with the Hollywood Stars with a 101-67 records, and they defeated the Stars 7-2 to gain the number one seed in the postseason playoffs. Although they lost in the playoffs to eventual league champion Oakland, they had had an exemplary season led by Luke Easter, Milt Smith, and Theolic Smith.

There was one other player, just coming into pro ball, who was briefly with the Padres in 1954. Floyd Robinson graduated from San Diego High School and signed with the Padres that year. They were unaffiliated at the time. He spent his first two seasons in the low minors before being called up for short stints at the end of each of those years.

The Indians reestablished their connection with the Padres in 1956 and the affiliation lasted through 1959. In 1956 and ’57, Floyd Robinson, now property of the Indians, spent the entire season with the Padres, batting .271 in 1956 and .279 in 1957. It would be a while before Robinson made it to the big leagues. He spent 1958 and ’59 in the Marines, and by the time he was released, San Diego was affiliated with the White Sox. Robinson became the property of Chicago. In 1960, Robinson batted .318 and was called up to the Sox at the end of the season. He played nine years in the majors, batting .283, and in 1962 he led the American League in doubles with 45 and was fourth in the league with 109 RBIs.

From 1956 through 1959, more players of color joined the Padres, some on their way down and one on the way up. Dave Hoskins, a pitcher who had begun his career with the Homestead Grays, was with the Indians in 1953 and 1954. In 1956, he was sent to the Padres, for whom he went 7–11.

“In the future, if our Negro players are (not) accepted, there will be no game. These youngsters are just as much a part of our organization as any of the others in camp.”6 — Hank Greenberg, April 1953

Billy Harrell was a star in both baseball and basketball at Siena College in New York and was signed by Greenberg after he graduated. In his second minor-league season, spring training in segregated Florida was stressful. Greenberg was supportive of his black players, and when accommodations were denied to Harrell and Brooks Lawrence, Greenberg expressed his indignation. Harrell made it to the Indians in 1955 and played at San Diego in 1957 before returning to the Indians at the end of that season. He was with the Indians through the end of 1958, after which he returned to the minors, having one last bite of the apple with the Red Sox in 1961.

Joe Caffie had some great seasons in the minors, but he only played 44 games in the majors in 1956–57. In 1956, after spending spring training with the Indians, he was farmed out to San Diego. He spent only 19 games with the Padres before being moved to Buffalo in the International League on May 12. He was batting .311 through 128 games with the Bisons when he was called up by Cleveland in September. He batted .342 in 12 games with the Tribe. The following year, after another good season with Buffalo, he appeared in 32 games with the Indians, batting .270.

Dave Pope’s career began with the Homestead Grays in 1946 and he first made it to the big leagues with the Indians in 1952. In parts of four seasons, he batted .265 in 230 games, and he played in the 1954 World Series. The Indians sent him to San Diego for the 1957 and ’58 seasons and he batted .313 and .316. Unfortunately, he would not return to the big leagues.

Larry Raines was with the Indians in 1957, getting into 96 games, but at the beginning of 1958, he was sent to San Diego, where he batted .303. He got called up to the Indians in September, but only got into seven games. They were his last games in the majors.

On his way up to the big leagues was Jim “Mudcat” Grant. He signed in 1954 and made it to San Diego for the 1957 season. With the Padres, he was 18–7 with a 2.32 ERA. The next year he made his debut with the Indians and was 145–119 in 14 major-league seasons.

In 1957, each PCL team had at least one player of color, following the lead of the San Diego Padres. As 1957 ended, change was on the horizon for the PCL. With the western migration of the major leagues, teams in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Hollywood would be replaced. San Diego remained in the league through 1968, secure in its legacy of having created opportunities for players of color in the Pacific Coast League.

ALAN COHEN serves as Vice President-Treasurer of the Connecticut Smoky Joe Wood Chapter, and is the datacaster for the Hartford Yard Goats, the Double-A affiliate of the Rockies. He has written 50 biographies for SABR’s BioProject, has contributed to more than 40 baseball-related publications, and has expanded his research into the Hearst Sandlot Classic (1946–65), which launched the careers of 88 major-league players. He has four children and six grandchildren and resides in Connecticut with wife, Frances, and their cat, Morty, and their dog, Buddy.

Sources

In additional to Baseball-Reference.com and the sources shown in the notes, the author used:

Costello, Rory. “Sam Jones.” SABR BioProject.

Engelhardt, Brian. “Billy Harrell,” SABR BioProject.

Jackson, Josh. “The Year After Jackie, Ritchey Integrated PCL,” MiLB.com, February 21, 2018.

Keller, Earl. “Ritchey, Padre Negro, Wrapping Up Regular Mask Job with Steady Raps,” The Sporting News, April 14, 1948.

Notes

1 Wendell Smith, “Smitty’s Sports Spurts,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 21, 1940.

2 Herman Hill, “John Ritchey: Young Man with a Future; Hits Hard in Clutch During First season,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 19, 1949.

3 Mitch Angus, “Padres Sign PCL’s First Negro Player,” San Diego Union, November 23, 1947.

4 John B. Old, “Coast Opens to 41,374; Oaks Draw Top Crowd,” The Sporting News, April 7, 1948.

5 “Jethroe Retains A. L. Batting Brown; .393 Mark Tops Loop,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 15, 1945: 12. Statistical records were haphazardly kept in the Negro Leagues. Seamheads.com’s Negro Leagues database has Wilson as 10th in batting average for the season with .315.

6 “Greenberg Backs Negro Farm Aces,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 11, 1953.