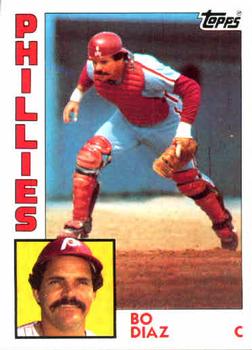

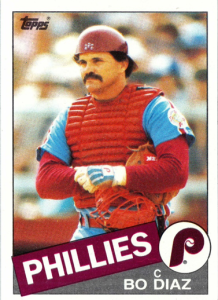

Bo Díaz

Venezuelan catcher Bo Díaz played for all or part of 13 seasons in the majors, plus 14 more in his homeland’s winter league. He helped the Philadelphia Phillies win a National League pennant in 1983 and was part of six champion teams with the Leones del Caracas.

Venezuelan catcher Bo Díaz played for all or part of 13 seasons in the majors, plus 14 more in his homeland’s winter league. He helped the Philadelphia Phillies win a National League pennant in 1983 and was part of six champion teams with the Leones del Caracas.

Díaz made it to the majors on the strength of his defense. The Scouting Report: 1983 remarked, “Díaz has a fine arm and can throw runners out with good consistency,”1 and the 1985 edition continued, “Díaz is an excellent receiver with good hands and blocks the ball well.”2 He was a solid, not spectacular, hitter – but he had good power, hitting 87 home runs in the majors and 57 more in winter ball. In the winter of 1979-80, he set a Venezuelan record with 20 round-trippers, a record that lasted until 2013.

Diaz’s other signal achievement was one of baseball’s rarities: an ultimate grand slam.3 The moment is etched in the memories of Phillies fans. April 13, 1983, Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia. Bottom of the ninth, two outs, Mets leading 9-6. Ace reliever Neil Allen was facing his first batter, Díaz. Longtime Phillies broadcaster Harry Kalas was calling the game. He went from calm to delirious in three seconds.

“Allen winds. The 2-and-1 pitch. A long drive. Deep left field … a grand slam! The Phillies have won the game 10-9! Unbelievable! Bo Díaz – a grand slam home run and the Phillies have won the game 10-9!”

Magical. The stuff of movies and the imaginations of baseball-playing boys everywhere.

In that moment, Baudilio José Díaz Seijas4 must have felt light years away from his small hometown of Cúa, Miranda, in Venezuela. Born March 23, 1953, to Ángel Rosendo Díaz, a bricklayer, and his wife, Juana Angelina Seijas, Díaz was the fourth child of six. He grew up with four brothers (Francisco Eduardo, Candelario José, Ángel Rosendo, and Ramón Darío) and a sister (Ana Celina).5 Ángel Díaz was a hard worker, but work was not always steady, money was frequently tight, and groceries were sometimes gotten on credit. They were a poor family, living in a small house, in an often-violent country, and daily life could be a struggle. With the family lacking the money to pay for bus rides to and from school or to buy the needed clothes, young Baudilio’s schooling ended after the sixth grade.

With formal education no longer available to him, he eventually went to work. However, driving a forklift in a cement plant is a completely unsuitable job for a 14-year-old boy, and he soon left Cúa to join an older brother in the capital city of Caracas, 40 miles to the north. There he worked in a car wash and later a ball-bearing factory. At 17, he was slated for military service, where he would fight the guerrillas – leftist rebels who were responsible for shootings, bombings, kidnappings, and other violent activities. It was not a prospect he relished.

Still, there was baseball. Díaz came from a baseball family and was raised in that tradition. While still working in construction, his father had been an outstanding player for three different teams during the 1930s into the 1950s. Baudilio had played consistently throughout his childhood and into his teenage years.6 And on weekends, he continued to play just as he had since joining his first Little League team at eight years old.7 The games were loosely organized and mostly for fun, but it was during those games in 1969 that scout Willie Paffen spotted Díaz playing in a factory league. (Paffen was most likely alerted to Díaz by “legendary talent bird-dog” Francisco Rivero, who also discovered Tony Armas, Manny Trillo, and Andrés Galarraga.8) In December 1970, with his father’s permission, he signed with the Boston Red Sox. Factory work and the specter of military service vanished.

Díaz was assigned to Class A in Winter Haven, Florida. From there he was sent to Pawtucket, Rhode Island. After playing in only one game, he moved on to Greenville, South Carolina, to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and finally to Williamsport, Pennsylvania – five clubs in one season.9 He spoke almost no English and had to get by with the help of any bilingual Latino player he could find. He made $450 a month and slept on cots in the clubhouses. Homesick and in pain from a knee injury sustained in his only game for Williamsport, facing the guerrillas might have seemed preferable.

Díaz reported to spring training in 1972 with his knee still badly damaged and underwent surgery to repair the cartilage, landing on the disabled list for what would be the first of many times in his career. As a result, he played just 14 games for Winter Haven that summer. In the winter of 1972-73, he began his career with the Leones del Caracas (Caracas Lions) in La Liga Venezolana de Béisbol Profesional. Díaz got 40 at-bats in 17 games that first season as the backup to the team’s veteran catchers. In one of his starts that winter, on January 6, 1973, Díaz caught a no-hitter by Urbano Lugo. Remarkably, 13 years later, on January 24, 1986, he was behind the plate again when Lugo’s son, also named Urbano, threw a no-hitter of his own for Caracas.

Díaz started the 1973 season in Elmira, New York. He graduated from clubhouse cots to a YMCA, which, he said, felt like a fine hotel. He bounced around the Red Sox minor-league system for four more seasons until he was called up from Pawtucket in September 1977. On September 6 he appeared in his first game for Boston and, in doing so, became the first catcher from Venezuela to reach the major leagues. After six years with Boston, he had made it. Except … he hadn’t. A significant roadblock stood in his way: future Hall of Famer Carlton Fisk. It was never going to happen for Díaz in Boston, and everyone knew it. In March 1978, he was traded to Cleveland.

As part of the trade, the Indians sent their best pitcher, Dennis Eckersley, to Boston. The expectations for Díaz were high, and manager Jeff Torborg was thrilled to have him. “The pitchers really like working with Bo. He’s outstanding behind the plate,” said Torborg. His strong, accurate throwing arm had earned him the nickname The Cannon, leading scout Jack Cassini to say that, “next to Johnny Bench, Díaz had the best arm he’d ever seen on a catcher.”10

That July, Díaz had his first major-league home run, and Torborg noted that he was a better hitter than they’d given him credit for.11 He was also, without a doubt, the best defensive catcher on the Indians roster. However, injuries plagued him still. Díaz’s Achilles’ heel wasn’t actually his heel – it was everything else: his left ankle (sprained), his right ankle (broken, ironically, when he shifted during a slide trying to protect the left one), his index finger (broken), and his thumb (sprained), all of which led Bob Sudyk in The Sporting News to call him “a walking accident”12 whose “bones resemble dry twigs.”13 Díaz was frustrated with himself, his teammates were losing patience, and the Indians may have questioned the wisdom of the trade.

Injuries notwithstanding, Díaz continued to play winter ball every year for Caracas, where he emerged as a standout. The only season in which he did not wear the Leones uniform was 1975-76, when Caracas merged with the Tiburones (Sharks) de La Guaira. For one season, a franchise called Tibuleones de Portuguesa existed. The 1977-78 season, during which Diaz caught 68 games, was the first time he played in the postseason for a Leones team that would ultimately win the championship.14 During the 1979-80 season, the first of three consecutive championship seasons for Caracas, he broke the league home-run record of 19, which had been set in the 1972-73 season by Bobby Darwin. Díaz’s record of 20 home runs, in just 247 at-bats (66 games) stood until Alex Cabrera, playing for the Tiburones, broke it in 2013. (This became a bitter pill for many Venezuelan baseball fans when Cabrera tested positive for anabolic steroids in April 2014.15) The Leones won another league championship in the 1981-82 season, which advanced them to the 1982 Caribbean Series. The Leones’ victory in that series was only the third time a Venezuelan team had won since the tournament’s inception in 1949 and was the first win for the Leones. Díaz batted .412 (8-for-19), hit two home runs, and was named the series’ MVP.16 The Leones’ next league championship would not come until 1986-87, which was also the last time Díaz spent a full season with the club.

After Díaz returned to Cleveland in 1981, everything began falling into place. Starting catcher Ron Hassey injured his knee, which meant Díaz finally got a chance to play regularly. He showed what he was capable of, hitting .356 in the first half of the season with 25 RBIs and being selected for the All-Star Team, the first catcher from Venezuela ever chosen.17 However, upon Hassey’s return, Díaz resumed his reserve role – an expected move but one that left him frustrated and, once again, on the back burner.

Coinciding with Díaz’s part-time status in Cleveland, the Philadelphia Phillies had a problem behind the plate. As Jeré Longman of the Philadelphia Inquirer dryly put it, “Bob Boone and Keith Moreland were throwing out runners with the regularity of Halley’s Comet.”18 This was a team with four catchers (in addition, Don McCormack and Ozzie Virgil) that still couldn’t hold down the running game. In November 1981, the Phillies and the Indians did everyone a favor by orchestrating a complex trade that sent left fielder Lonnie Smith and pitcher Scott Munninghoff to Cleveland for Díaz. (Smith was dealt to St. Louis immediately.)

Calling it a “favor” may be putting too positive a spin on the way Phillies fans felt at the time. Not renowned for their tact and good humor, they were irate over the loss of the popular Smith. Bill Conlin later wrote in The Sporting News that Díaz had been greeted by Veterans Stadium fans “with the warmth reserved for ax murderers.”19

Philadelphia reporters, while not openly hostile like the fans, were on the fence. In a profile for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Dan Coughlin described him as moody, injury-prone, slow to heal, and sensitive. On the other hand, he wrote, “Díaz is your composite major league catcher. He has a strong arm. He is smooth behind the plate. He is an acceptable hitter.” Speed, however, was never among Díaz’s gifts. Coughlin continued, “He is as slow as the legislative process.”20

If Díaz was upset by the media’s assessment of him or the fans’ attitude, he didn’t show it. And yet, he wasn’t naïve; he knew the move would present challenges. Long before the days of interleague play, he was well aware of the difficulties inherent in switching from one league to the other. Furthermore, his major concern (unfounded, as it turned out) was how he would be received by the sometimes prickly Steve Carlton.21 (By 1980, Carlton had won three Cy Young Awards and was notoriously particular about his catchers.) Still, Díaz was happy to be out of Cleveland and looked forward to a chance to play regularly. He also had manager Pat Corrales, a former catcher himself, firmly in his corner. Corrales had managed Díaz in Venezuelan winter ball in 1976-77 and had watched him over the years. Tired of seeing so many stolen bases, he had long advocated for Díaz. In the 1981 season, the Phillies caught 41 of 165 basestealers, with a third of them being picked off by the pitchers.22 In spite of the fans’ misgivings, The Cannon was clearly needed.

In time, the sportswriters and fans came to appreciate their new catcher. When Díaz, in his typical fashion, downplayed talk of having a cannon for an arm, writer Jayson Stark begged to differ. Stark took Phillies pitching to task, but praised Díaz, saying, “On Mookie Wilson’s steal in the third inning, Díaz got rid of the ball as quickly as any human could do it. And when the ball got to second, it was six inches off the ground, at the right corner of the bag. A dead solid strike.”23Later in the season when Díaz had a two-home-run game, the fans, apparently having forgiven him for being part of the Smith trade, gave him a standing ovation and demanded that he appear from the dugout.24

Díaz also had an attitude that was completely focused on the good of the team. He wanted to play well but would have gladly traded his personal success for the team’s success. After a 7-4 loss to the Cardinals in April 1982, Díaz was described as “disconsolate” because his team was 3-11 and had lost three straight – disconsolate even though he’d gone 4-for-4 with two home runs, two doubles, and four RBIs.25

In September 1983, Díaz again had two home runs plus three singles in a game that he declared his greatest day, not because of his own performance, but because his team had won and clinched the NL East.26 In the World Series that followed, he was exceptional. He started all five games and finished with a .333 average. For the Phillies, however, it was a dismal Series; they won the first game but lost the next four to the Baltimore Orioles.

During the Series, when Díaz and Baltimore catcher Rick Dempsey were squaring off against each other, an incredible story emerged from their shared past as winter-ball teammates. In an interview with the New York Times, Dempsey told of a game in Maracaibo, Venezuela, when he was the Leones’ starting catcher, and Díaz was his backup. It was November 1973, and an on-field brawl involving Dempsey continued into the parking lot after the game. The Leones, still in their uniforms, were easy targets for an angry Maracaibo mob as the players tried to get to their cabs.

Dempsey eventually made it through the melee and got in the back seat with a few other teammates, while Díaz jumped in the front. But being in the cab offered little protection. An irate fan threw a brick through the windshield, and the broken glass cut Díaz’s neck. Bleeding profusely, Díaz lost consciousness. Quick-thinking Dempsey used the catcher’s pad he still had in his pocket to stanch the blood. With the crowd nearly rioting and Díaz quite possibly bleeding to death, Dempsey and the other players screamed at the cab driver to get to the hospital.27 Twenty-seven stitches later, Díaz was out of danger, but years later, he still bore a scar on his neck from that night.28

Díaz returned to Caracas for the 1983-84 season but played just four games that winter. Physical troubles had appeared once again, and in 1984, he played very little in spring training due to chronic lower-back pain. He rehabbed with exercise and medication and, for the first time, admitted that an occasional rest might help him.29 He did not, as feared, begin the season on the disabled list. In fact, he had one of the best starts of his career, hitting .295 with seven RBIs, which only made a torn ligament in his left knee especially disappointing and difficult to bear. In late April, a home-plate collision aggravated a previous injury and landed him on the DL. In early May, he had surgery to repair the knee with a projected recovery time of up to five weeks.30 A second surgery in August on the same knee effectively ended his season. (Catcher Mike LaValliere, his Phillies teammate, once said of Díaz’s knees, “They’re scarred and swollen and every time he squats to catch, it makes me hurt just watching him.”31)

By late 1984 and into early 1985, the Phillies had Díaz on and off the market at various times. His frequent stints on the DL and the solid play of Ozzie Virgil seemed to make him nonessential. Publicly, Díaz said he was prepared for whatever came his way, be it Atlanta, Toronto, or Seattle, all mentioned as trade possibilities. Privately, however, he was disappointed that the Phillies considered him “so expendable.”32

After taking off the whole winter, by spring training 1985, Díaz was rested and almost fully healed. He wanted to stay with the Phillies and wanted to play regularly. He was not interested in being the backup catcher and considered himself the starter. However, after capably stepping in for Díaz in 1984, Ozzie Virgil also considered himself the starter.33 If Díaz had an edge, it was that the pitching staff liked him. John Denny, Jerry Koosman, and Steve Carlton all preferred Díaz to Virgil. They felt he called a better game and was a better defensive catcher.34 In an article in the Philadelphia Daily News, Bill Conlin described it this way:

He] has quiet ways of finding out what they want from him in the way of pitch sequences, location signs and target placement. All are integral but unsung fine points. It’s no secret that Bo Díaz is a member in good standing of Lefty’s [Steve Carlton’s] exclusive club of preferred catchers. That gives Díaz some catching clout that Ozzie Virgil lacks.35

But when Opening Day 1985 rolled around, Virgil was the starting catcher and would be for all of April while the Phillies kept an eye on Díaz’s progress. What followed was another run of bad luck. In a mid-April exhibition game, he was hit by a pitch that broke two bones in his right wrist. In May, while still on the DL for his wrist, he landed in the hospital with kidney stones.

By July, trade rumors were flying again. Pete Rose, now back in Cincinnati as a player-manager, made no secret of his goal to acquire his former teammate. Díaz, recovered but frustrated by his lack of playing time, was ready to go, if not to the Reds, then anywhere. “I really want to get out of here, just so I can play,” he said. “I know my time for retirement is coming, but I think I can help somebody for two or three years.”36

The Phillies were well aware of Díaz’s desire to play regularly and of his frustration at not doing so. Manager John Felske, a former backup catcher himself, was particularly sympathetic. But the team was not willing to give him away. “If we’re going to trade him, we’re going to get quality for him. We have a quality player, and if someone wants him, we’re in a position to demand what we want,” Felske said.37

Finally, on August 8, 1985, Díaz was traded to Cincinnati.38 Rose, Reds general manager Bill Bergesch, and his new teammates were ecstatic. “We are back in business,” said shortstop (and fellow Venezuelan) Dave Concepción.39 Upon his arrival at the Cincinnati clubhouse, starting pitcher Mario Soto hugged him like a long-lost brother.40 And Bergesch, after praising Díaz and confirming his physical soundness, boiled it to down to this: “When you have a chance to get Bo Díaz, you must jump at it.”41

Díaz’s hitting got off to a slow start (.103 in 39 at-bats), but he adjusted well to the pitching staff. A few weeks later, in a game against the Cubs, he broke out of his slump and doubled in the game-winning run.42 That double was the beginning of a 13-game hitting streak, the longest of his career. He finished the season batting .261 for the Reds (.245 overall). And as the focus shifted to 1986 and a shot at the pennant, the Reds knew they would start the next season with a capable defensive catcher for the first time since Johnny Bench retired in 1983.43

Still, in a team populated with good hitters, Díaz knew his main job was to support the pitchers and to call a strong game. (In fact, the staff ERA dropped nearly a point after his arrival,44 and by the end of the 1989 season was at its lowest with Díaz behind the plate.45) Without exception, he was praised by the Reds pitching staff. Guy Hoffman recalled a time he faced a batter he didn’t know how to pitch to. He deferred to Díaz, thinking, “Whatever you call, I’m going to throw.” Hoffman, laughing, said, “Bo struck him out on four pitches. I didn’t strike him out. Bo struck him out.”46

Díaz – described that year as “a classic free swinger with a stance for every occasion”47 – had a solid 1986 season as Cincinnati’s primary catcher. He hit .272-10-56 in 134 games. That summer, he also set an unusual record. On June 27, in a 12-inning game against San Francisco, he threw out second baseman Robby Thompson on four stolen-base attempts, making him the first major-league catcher to throw out the same baserunner four times in a game.48

That winter, Díaz caught 35 games for another Leones championship team, and in 1987 he made his second appearance on the All-Star team, with USA Today calling him “a steady force for the first-place Reds.”49 He was the National League player of the month for July, hitting .351 with 5 home runs and 23 RBIs. But as the end of the season approached, Rose considered the possibility that he should rest his catcher more.50 After August 5, Díaz batted .171, and when the season was over, Rose admitted that his biggest mistake that season had been overworking Díaz.51 (Indeed, Díaz sat out the winter season and the following two as well.) Nevertheless, Díaz continued to be greatly valued by his manager, so much so that he was one of Rose’s “untouchables,” nine players who were off-limits as possible trades.52

By late July 1988, Díaz, that “classic free swinger,” held a dubious distinction: he had the highest ratio of at-bats to walks in the major leagues, walking once in every 61.75 at-bats. (The MLB average was one walk per 10.88 at-bats.) “Díaz might consider being a little choosier at the plate,” chided USA Today.53 A week later, Rose fired back. “Bo just likes to swing. He likes to hit the ball. He might swing at one near his shoe-tops and another one over his head.”54 Later that same day, Díaz himself responded – with his bat. With two on and two out, he swung on a 3-and-0 pitch from the Dodgers’ Don Sutton and drilled it over the left-field wall.55

More worrisome than Díaz’s base-on-balls total, however, was the onset of a new physical issue, tendinitis in his right shoulder, and the return of an old one. As the season drew to a close, he once again needed surgery on his troublesome left knee to repair a small ligament tear. Díaz, who batted and threw right, saw his average drop from .270 in 1987 to .219. That was probably attributable, at least in part, to the pain in his shoulder. The knee surgery was not regarded as serious, and the Reds were optimistic that he would be strong in 1989. “His skills haven’t diminished,” said general manager Murray Cook. “He can still throw. He never could run. His catching is fine, and he swung the bat fine when he wasn’t hurting.”56

After unexpected visa delays for Díaz and two other players, he reported to spring training in 1989 looking fit and with only minimal lingering knee issues. However, in March he needed an emergency leave. His younger son had suddenly become seriously ill and had to have a benign tumor removed from the back of his head. Once his son was on the mend, Díaz was sent to extended spring training in Florida for a week to sharpen his skills. He didn’t understand or agree with the move, which capped a very difficult spring for him.57

The season proceeded unremarkably with the exception of two events. In June, Díaz hit his first home run since the previous August and in doing so broke a 3-3 tie with the Dodgers. His reaction must have stunned and delighted his fans. “As it arced over the left-center-field fence, Díaz was rounding first base, shaking both hands in the air – a most unusual display of emotion from the intense, but generally unflappable catcher.”58

Then, on July 9, 1989, Díaz played his final big-league game, though he didn’t know it at the time. Once again, his left knee was the culprit, and in early August, he had his third surgery to repair it. He finished the season having played in only 43 games and with a batting average of .205. He was at the end of a two-year contract with the Reds and in November was granted free agency. He had a career batting average of .255 in the majors and a fielding percentage of .986; he’d also thrown out 34 percent of enemy basestealers. He was 37 years old and wanted to continue playing, but he remained unsigned for the 1990 season. His longtime agents, Randal and Alan Hendricks, later said that he was just too beaten up, particularly with a knee that would not cooperate, to play in 1990.59

In October 1990, the Cincinnati Reds were in postseason play, and Díaz was in Venezuela, playing once more for Caracas. He told a reporter, “I played hard and gave it my best in Cincinnati, and I grew to love the people of the city because they treated me well. I’m rooting for them all the way in the playoffs and the World Series.”60 As Díaz watched from 2,000 miles away, the Reds swept the Oakland Athletics in the World Series, four games to none.

Baudilio Díaz, born in a tiny house in Cúa, had worked his way to an upper-middle-class life and a two-story home in Caracas. It was there that his tragic death took place on November 23, 1990. The day was windy, and the signal from the home’s satellite dish was spotty. He went to the roof and attempted to adjust the dish, which slipped and fell on him, crushing his neck and killing him instantly. He left behind his wife of 11 years, María Carolina, and his sons, Bo Daniel, 9, and Joshua, 6.

Díaz was idolized in Venezuela, and his death was a national tragedy. News crews were on the scene immediately, and just before 2:00 P.M., radio stations interrupted their regular programming to announce that he had died.61

Three days before his death, Díaz had quit the Leones unexpectedly amid a dispute with manager Phil Reganover Regan’s use of him as a bullpen catcher. Díaz had been replaced by 23-year-old Carlos Hernández, who had made his debut with the Los Angeles Dodgers earlier that year and who had been the Leones’ starting catcher for the previous two seasons. Regan felt Hernández’s need to develop as a catcher was more important than Díaz’s desire to prepare for a possible return to the majors. (Inconceivable as it seems, Díaz even considered the possibility of playing for another team, if it meant he could catch every day, and the rival Tigres de Aragua were calling him nonstop.)62

But in the end, after a major-league career that included significant tenures with Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Cincinnati, Díaz’s baseball identity was most strongly tied to his native country and the Leones. His body was dressed in his Leones uniform, number 25, which the club promptly retired.63 His December 13 funeral at the University of Caracas stadium was attended by 3,500 relatives, friends, fans, and politicians, including the president of Venezuela.

Fans and teammates throughout Venezuela and the United States grieved for the man described as tough and stoic but with a kind heart. Paul Owens, who managed Díaz on the 1983 NL championship team, said, “Bo was as nice a fellow as you’d want to meet. He was a good family man. A fine gentleman. I always admired him.”64

“He went about his job in a very businesslike fashion,” said Reds teammate Eric Davis. “When Bo wasn’t playing, you knew he had to be hurt because he was so tough.” Barry Larkin, another teammate, recalled, “We were young, and Bo showed us a lot of leadership. He was quiet, but he led by example.”65

Randal and Alan Hendricks described him as a private but very happy person. “Our best memories of him are his ever-present smile when dealing with us. He was an appreciative person, which made representing him a privilege.”66

In 2006, Díaz was inducted into the Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame, which called him one of the bravest players ever to play the game, given the numerous injuries he sustained during his career.67 Sportswriter John Erardi echoed this sentiment, calling Díaz “a tough customer, a gamer who played hurt and rarely complained.”68

Even now, the sadness of Díaz’s untimely death lingers, especially for Venezuelans, and his country continues to honor him. In 2013, the Venezuelan government opened the first phase of a $5 million sports complex called Domo Baudilio Díaz. A second phase has been approved.69 It appears, however, that construction has not started. (Given the current political and economic climate in Venezuela, this is unsurprising.)

Also, in 2013, the blog Planeta Béisbol featured a story from a fan who told of a game he watched as a 12-year-old between his team, the Cardenales de Lara, and the visiting Leones. The game was in 1979, and a home run by Díaz helped the Lions defeat the Cardinals. But it was after the game that the day took a memorable turn:

“As we walked back to our car, I saw the Lions’ bus coming. Back then, people would throw rocks at the visiting teams’ buses and yell insults at the visiting players. This happened at ballparks all over the country.

“Imagine my surprise when suddenly a bus window opened and none other than Baudilio Díaz stuck out his head. My jaw dropped when I realized he was tossing out bats, gloves, and balls to the kids who ran alongside the bus.

“That was the first time I remember seeing, in any ballpark, people applauding the visiting team’s bus, especially after the visitors had beaten the home team.”70

And in November 2013, Díaz’s hometown named a ballpark for him. The dedication ceremony brought together relatives, friends, and the town’s mayor to celebrate “the pride of Cúa” and to unveil a sculpture of him. He is immortalized in bronze crouched in his catcher’s gear with a ball in his glove.71

Díaz’s importance to the Leones and to baseball in the Caribbean remains undiminished. In 2019, he was selected for the Caribbean Baseball Hall of Fame.72 And he continued to figure heavily in the Leones’ media guides both as a significant part of the team’s story over a 20-year period and as a record holder.73 Over time, he has become mononymous: in much that is said and written about him, he is simply Baudilio – no last name or explanation needed.

In 1987, two years after Díaz’s arrival in Cincinnati, John Erardi profiled him for the Cincinnati Enquirer and described his quiet, introverted ways. 74 He was warm, polite, and kind, but he was simply not a big talker and never sought to draw attention to himself. Erardi described a Reds-Astros game that resumed after a 2-hour, 20-minute rain delay:

“When only a few hundred fans remained to watch the last two innings of the game, it was suggested to [second baseman] Ron Oester that of all the players on the field, perhaps only Díaz could have enjoyed the sparsity of the crowd, and that the only way he would have enjoyed it more is if the last 200 had had the good sense to go home, too. Oester shook his head in disagreement. ‘Bo wants to be appreciated,’ Oester said. ‘He might not come out and say it, but that is what he feels.’”

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used clippings from Díaz’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York. Also helpful were Retrosheet.com, BaseballProspectus.com, and especially Baseball-Almanac.com and Baseball-Reference.com. For biographical information and background on Díaz’s early life and career, the author relied heavily on the article “At Last Díaz Finds a Home,” by Jeré Longman in the Philadelphia Inquirer, June 28, 1982.

Grateful acknowledgment to Díaz’s agents, Randal and Alan Hendricks, with whom the author corresponded by email. Sincere gratitude to Rory Costello.

Díaz’s statistics in Venezuelan winter ball: http://www.pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/mostrar.php?ID=diazbau001

Notes

1 Marybeth Sullivan, ed., The Scouting Report: 1983 (New York: HarperCollins, 1983), 544.

2 Marybeth Sullivan, ed., The Scouting Report: 1985 (New York: HarperCollins, 1985), 544.

3 Through the end of the 2022 season, this feat had been achieved 33 times. Díaz’s was number 15.

https://www.baseball-almanac.com/feats/walk_off_grand_slams.shtml, accessed July 4, 2023.

4 Formal naming customs in Spanish place the mother’s maiden name after the father’s last name; however, the paternal family name is commonly used. As such, he is known by and will be referred to here as Díaz.

5 “Baudilio Díaz: ‘El Cambao’ que estableció récords en el béisbol profesional,” https://globovision.com/article/especial-baudilio-diaz-el-cambao-que-batio-records-en-el-beisbol-profesional, March 23, 2017, accessed November 23, 2020.

6 “Baudilio Díaz: ‘El Cambao’ que estableció récords en el béisbol profesional.”

7 On July 29, 1967, with his team one game away from a trip to the Little League World Series, a 6.5 magnitude earthquake occurred near Caracas. The aftermath was devastating: 240 deaths, 1,536 injuries, and $100 million in property damage. On a smaller scale, the devastation meant that a team of teenage boys could not leave the country to finish their season. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/learn/today/index.php?month=7&day=29.

John Erardi, “Ability Has Earned Respect from Teammates and Foes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 5, 1987: C-6.

8 Richard Justice, “Galarraga Well-Kept Secret,” Edmonton (Alberta) Journal, July 3, 1988: F2.

9 His Sporting News contract card shows him assigned to Winston-Salem from June 21 to July 19.

10 Russell Schneider, “Pruitt Tells Indians Not to Boo-Hoo Over Bo,” The Sporting News, May 6, 1978: 8.

11 Bob Nold, “Indians’ Hood Outstanding in 8-2 Win Against Cubs,” Akron Beacon Journal, March 16, 1979: C-1.

12 Bob Sudyk, “Hassey No. 1 in Tribe’s Mitt Plans,” The Sporting News, November 3, 1979: 54.

13 Bob Sudyk, “Denny Makes Optimistic Pitch to Indians,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1980: 40.

14 The Leones won the championship in 1972-73 with Díaz as part of that team, however he did not play in the postseason. He did see postseason play in 1974-75, 1975-76, and 1976-77, but the Leones did not advance past the semifinals in those years.

15 Juan Pablo Zubillaga, “PEDs, Tainted Records, and the Colorado Rockies,” http://www.rockieszingers.com/2014/04/29/peds-tainted-records-colorado-rockies/, April 4, 2014, accessed March 30, 2017.

16 The Leones del Caracas are a member of La Liga Venezolana de Béisbol Profesional (LVBP) [Venezuelan Professional Baseball League]. During the years Díaz was active with the Leones, the team won the league championship in the 1972-73, 1977-78, 1979-80, 1980-81, 1981-82, and 1986-87 seasons. The Serie del Caribe [Caribbean Series] is a postseason tournament played annually in early February between the championship teams of the Caribbean winter leagues: the Dominican Winter League, Mexican Pacific League, Puerto Rican Winter League, and Venezuelan League.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Venezuelan_League.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Caribbean_Series.

17 https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=diazbo01.

18 Jeré Longman, “At Last Díaz Finds a Home,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 28, 1982: 7-C.

19 Bill Conlin, “Tampering With Solid Lineup Hurts Expos,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1982: 35.

20 Dan Coughlin, “Phils’ New Bo Is No Perfect 10, but He’s Improving,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 20, 1981: 6-C.

21 Hal Bodley, “Take Glove, Not War,” Wilmington (Delaware) News Journal, February 28, 1982: D7.

22 Jayson Stark, “Smith Trade Is a Prelude for Big Deal to Come,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 20, 1981: 10-C.

23 Jayson Stark, “Phillies’ Bo Can’t Be ‘10’ All the Time,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 2, 1982: 10-D.

24 Rusty Pray, “Phillies Fans Finally Accepting Competitive Bo Díaz,” Camden (New Jersey) Courier-Post, May 11, 1982: 1C.

25 Jeré Longman, “Inept Phils Succumb to Cards, 7-4,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 25, 1982: 10-E.

26 “Phils Win NL East Crown,” Albuquerque Journal, September 29, 1983: D-1.

27 Ira Berkow, “The Dempsey-Díaz Affair,” New York Times, October 12, 1983: B-13.

28 “The Greatest Fans in the World?” Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, September 16, 1977: 17. In his book El Béisbol: Travels Through the Pan-American Pastime (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1989: 237), travel writer John Krich describes Venezuelan baseball fans as “single-minded and vicious” and points to the Díaz-Dempsey incident as proof. But he gets the story backward and has Díaz saving Dempsey’s life.

29 Ray Finocchiaro, “Díaz Aching to Strike Back,” Wilmington Morning News, March 29, 1984: C3.

30 Peter Pascarelli, “Surgery Will Sideline Díaz 3 to 5 Weeks,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 5, 1984: 1-C.

31 David Pietrusza, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman, eds., Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Total/Sports Illustrated, 2000), 286.

32 Jayson Stark, “Trade Talk and Knee Leave Díaz Uncertain,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 23, 1985: 1-F.

33 Ray Finocchiaro, “Díaz, Daulton Try to Catch Up with Virgil,” Morning News, February 26, 1985: C2.

34 Ray Finocchiaro, “Díaz catching his share of bad breaks,” Wilmington Morning News, April 21, 1985: C7.

35 Bill Conlin, “Scouts Find Díaz Debut Impressive,” Philadelphia Daily News, March 13, 1985: 98.

36 Mark Whicker, “Time’s Not on Díaz’s Side,” Philadelphia Daily News, July 22, 1985: 87.

37 Rich Hofmann, “Bo Holds Trading Block Party,” Philadelphia Daily News, July 24, 1985: 89.

38 He was traded with minor-league reliever Greg Simpson for infielder Tom Foley, infielder-catcher Alan Knicely, and a player to be named later (pitcher Freddie Toliver). See Transactions: https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/d/diazbo01.shtml.

39 Greg Hoard, “Reds Elated Over Acquisition of Díaz,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 8, 1985: B-1.

40 Greg Hoard, “Reds’ Díaz Delighted As Rumor Becomes Reality,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 9, 1985: D-1.

41 “Reds Deal for Díaz,” Columbus (Indiana) Republic, August 8, 1985: B1.

42 “Bo Díaz and Buddy Bell ‘Arrive’ in Cincinnati Victory,” De Kalb (Illinois) Daily Chronicle, August 26,1985: 9.

43 Rick Van Sant, “Reds ’85 Performance Spurs Dreams For ’86,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 13, 1985: 4D.

44 Marybeth Sullivan, ed., The Scouting Report: 1986 (New York: HarperCollins, 1986), 421.

45 Staff ERA with Díaz: 3.57; with Terry McGriff: 3.72; with Jeff Reed: 3.66; with Joe Oliver: 4.05

https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/split.cgi?team=CIN&t=p&year=1989.

46 Erardi, “Ability Has Earned Respect from Teammates and Foes.”

47 Sullivan, The Scouting Report: 1986, 421.

48 https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=diazbo01;

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CIN/CIN198606270.shtml

49 “National League All-Stars,” USA Today, July 10, 1987: 9C.

50 Rick Van Sant, “Díaz Powers Reds, Rekindles Memories,” Columbus (Indiana) Republic, August 5, 1987: B1.

51 “Baseball Notebook: N.L. West,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1987: 26.

52 Greg Hoard, “Cincinnati Might Deal Parker for Pitching,” USA Today, October 2, 1987: 5C.

53 “Time to Go for a Walk,” USA Today, July 29, 1988: 5C.

54 “Slip in This Name Among Leaders in Slips of Tongue,” Los Angeles Times, August 9, 1988: 2-Part III.

55 https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CIN/CIN198808090.shtml.

56 Greg Hoard, “Healthy Díaz Can Solve Problem at Catcher, Reds Say,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 6, 1988: C-4.

57 “Reds’ Díaz Not Happy in Florida,” Kokomo (Indiana) Tribune, April 16, 1989: 41.

58 “Big Home Runs by Díaz, O’Neill Carry Reds 5-3,” Nashville Tennessean, June 27, 1989: 4-C.

59 Randal and Alan Hendricks, email to Andrea Long, December 1, 2016.

60 John Erardi, “Díaz Was a Professional, with Warm Heart,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 24, 1990: D-1.

61 Carlos Figueroa Ruiz, “Tragedia de Baudilio Nos Enlutó Hace 25 Años,” http://www.liderendeportes.com/noticias/beisbol/tragedia-de-baudilio-nos-enluto-hace-25-anos.aspx#ixzz4Lx2CWPbl, accessed October 2, 2016.

62 Carlos Cárdenas Lares, Leones del Caracas: Crónica de una Tradición (Caracas, Venezuela: Fondo Editorial Cárdenas Lares, 1992), 261.

63 The other 11 numbers retired by the Leones belonged to Pompeyo Davalillo, Víc Davalillo, César Tovar, Tony Armas, Urbano Lugo (the son), Gonzalo Márquez, Alfonso “Chico” Carrasquel, Omar Vizquel, Henry Blanco, Luis Aparicio (retired leaguewide), and Andrés Galarraga. http://www.leones.com/uniformes.php, accessed October 15, 2020.

64 “Satellite Dish Crushes Díaz,” http://articles.philly.com/1990-11-24/sports/25929095_1_satellite-dish-bo-Díaz-baruta, accessed September 12, 2016.

65 Erardi, “Díaz Was a Professional, with Warm Heart.”

66 Randal and Alan Hendricks email.

67 “Baudilio José Díaz,” http://www.museodebeisbol.com/salon_fama_venezolano/detalles/2006/baudilio-jos-daz, accessed July 4, 2023.

68 John Erardi, “Díaz Dies in Rooftop Accident,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 24, 1990: A-1.

69 “Gobierno Nacional Inauguró Domo Deportivo-Cultural en Charallave,”

http://www.avn.info.ve/contenido/gobierno-nacional-inaugura-domo-deportivo-cultural-charallave, accessed September 16, 2016.

70 Frank Pereiro, “Alex Cabrera le Pide Paso al Gran Baudilio Díaz,”

https://planetabeisbol.com/threads/alex-cabrera-le-pide-paso-al-gran-baudilio-diaz.4180/, November 29, 2013, accessed June 22, 2017.

71 Dulce Feliciano, “Develan Estatua en Honor a ‘Baudilio Díaz’ en Estadio de Cúa,” http://lagranciudad.net/home/develan-estatua-en-honor-a-baudilio-diaz-en-estadio-de-cua/, accessed October 3, 2016.

72 The 2019 Caribbean Series was moved at the last minute from Barquisimeto, Venezuela, to Panama City, Panama, and the Hall of Fame ceremony was postponed. Díaz and the rest of his class were inducted in 2020 alongside the 2020 members. David Venn, “5 things to know about the 2020 Caribbean Series,” https://www.mlb.com/news/caribbean-series-changes-for-2020, accessed November 23, 2020.

73 Leones del Caracas Guía de Medios 2018/2019 (Caracas: Caracas Baseball Club, C.A., 2018), 264.

74 Erardi, “Ability Has Earned Respect from Teammates and Foes.”

Full Name

Baudilio José Díaz Seijas

Born

March 23, 1953 at Cua, Miranda (Venezuela)

Died

November 23, 1990 at Caracas, Distrito Federal (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.