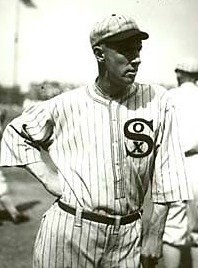

Swede Risberg

A light-hitting, rifle-armed shortstop who played a key role in baseball’s biggest scandal, Swede Risberg was a rising young player in the American League when he was banned from the game at age 25. The youngest member of the Black Sox, he always found his home state of California and the Pacific Coast League preferable to the harsh spotlight of the majors. “He would gleefully toss up his chances for fame and lucre,” a reporter wrote in 1917, “and take the first train back to the Pacific Coast, where he knows everybody and is known by everybody.”1 Risberg managed to survive in Chicago by adopting a tough veneer that led to frequent fisticuffs and a reputation for toughness, excitability, and standoffishness. That reputation was enhanced by the events of 1919, when he helped orchestrate the Series-fixing plot that resulted in his banishment from baseball and the wrecking of the White Sox franchise.

A light-hitting, rifle-armed shortstop who played a key role in baseball’s biggest scandal, Swede Risberg was a rising young player in the American League when he was banned from the game at age 25. The youngest member of the Black Sox, he always found his home state of California and the Pacific Coast League preferable to the harsh spotlight of the majors. “He would gleefully toss up his chances for fame and lucre,” a reporter wrote in 1917, “and take the first train back to the Pacific Coast, where he knows everybody and is known by everybody.”1 Risberg managed to survive in Chicago by adopting a tough veneer that led to frequent fisticuffs and a reputation for toughness, excitability, and standoffishness. That reputation was enhanced by the events of 1919, when he helped orchestrate the Series-fixing plot that resulted in his banishment from baseball and the wrecking of the White Sox franchise.

Charles August Risberg was born on October 13, 1894, in San Francisco, the youngest of three children of a Swedish-born longshoreman, Charles Peter, and his Danish wife, Trisini. Risberg was raised in the North Beach section of San Francisco and survived the great earthquake in 1906. Although he liked to say in later years that he had dropped out of school by the third grade because he had “refused to shave,”2 Risberg’s formal education extended to at least the eighth grade at Hancock Grammar School.3 By the time he was 14 he was a star pitcher for the school team, and he soon won wide acclaim as a semipro pitcher in the Bay Area.

In 1912 the 17-year-old Risberg won a tryout in spring training with the Vernon Tigers of the Pacific Coast League. The Los Angeles Times reported that “the youngster looks like a fixture,” but Risberg managed to pitch in only two games for the Tigers that year.4 In 1913 he spent the year in the low minor leagues, struggling in 11 appearances for Spokane (Washington) of the Northwestern League before moving on to Ogden (Utah) of the Union Association, where he was converted to shortstop. He hit well (.284 with 30 extra-base hits) but made a whopping 68 errors in 82 games. Returning to Ogden in 1914, the 19-year-old continued to improve as a position player, batting .366 and earning another chance with the PCL Tigers at season’s end.

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

He soon became a full-time utilityman for the Tigers, playing 175 games in 1915 and 185 in 1916 despite indifferent hitting performances, and spending time at first base, second base, shortstop, the outfield, and, occasionally, the pitcher’s mound. During one game, Risberg reportedly “left his place at second base, took the mound and not only staved off a rally, but pitched his team to a victory.”5

Risberg’s strong arm was both an asset and a liability; his throwing ability garnered praise, but once, in a fit of anger, Risberg punched an umpire who called a third strike on him. In another incident, he got into a fistfight with Salt Lake player Tommy Quinlan, who had flattened Risberg with a takeout slide at second base.6

Risberg’s manager at Vernon, former Chicago White Sox pitcher Doc White, gushed about his young star, calling him “the best utility man in these United States,” and adding, “The big leagues haven’t his equal. … I have never seen anything quite like him.”7 White recommended Risberg to Charles Comiskey, who had the right of first refusal on all Tiger players. In March 1915 Comiskey got a firsthand look at Risberg when the White Sox faced the Tigers in four spring exhibition games; Swede helped win one of the contests with a home run.8 The next year, during Risberg’s fifth minor-league season, Comiskey purchased his contract for $4,000.9 Risberg, who at 6 feet tall and 175 pounds was one of the largest shortstops to play in the majors before World War II, replaced 129-pound Zeb Terry on the 1917 Sox roster.

Risberg’s transition to the major leagues wasn’t smooth. A newspaper article written in June 1917 revealed that he suffered from “the worst case of homesickness in the history of the Sox aggregation,” adding that “he misses the soft blue skies of California. He wants to be back where the sun shines and his wife can cheer him on from the grand stand.”10 Risberg – a right-handed “marvel at shortstop” – even asked that Comiskey send him home, but the request was denied.

Risberg’s 1917 batting average of .203 was abominable, but because of his defensive skills he played in 149 games that year for the White Sox. Still, Risberg maddened Chicagoans with his inconsistency. “He is liable to be a sensation one minute and a crape hanger the next, for he can throw them away as far and as hard as anyone,” Hugh Fullerton wrote. “The boy is high strung, nervous, and inclined to panic. … His fault is that he seems striving constantly to conceal his nervousness under a veneer of pretended carelessness and coolness.”11 Late in the season, Risberg went into a slump and as the White Sox fought for the American League pennant, manager Pants Rowland benched him. Buck Weaver shifted to his old position at shortstop and Fred McMullin took over at third base. Risberg only pinch-hit twice as the White Sox beat the New York Giants in the 1917 World Series. Heading into the 1918 season, Rowland told Risberg he would have to hit better if he wanted to keep his job.

The year 1918 was chaotic for professional baseball, as the “work or fight” order prevented players from being exempted from war duties. Though he batted an improved .256, Risberg appeared in just 82 games before leaving the team on August 8 and heading home to San Francisco. He had told Comiskey and the press that he would enlist in the Army upon his arrival, but instead he found work in an Alameda, California, shipyard owned by Bethlehem Steel. Although Risberg’s job was termed essential and enabled him to avoid the draft, it consisted largely of playing baseball, as he batted .308 for the shipyard team. Risberg had made his contribution to the war effort in May, however, when he had to skip town to avoid arrest after punching a man at the White Sox’ team hotel in New York for complaining about the Red Cross’s persistent fundraising efforts.12

In 1919 Risberg signed a two-year contract worth $3,250 a season, making him one of the lowest-paid White Sox starters but commensurate with the 24-year-old’s erratic performance thus far in his career.13 He again hit .256, but recorded a career-high 19 stolen bases in 119 games as the White Sox returned to the World Series for the second time in three years.

But Risberg’s season was a rocky one. As Chicago slumped in June and fell out of first place for the first time, new manager Kid Gleason turned to the tried-and-true lineup of Buck Weaver at shortstop and Fred McMullin at third, bumping Risberg from a starting job. The White Sox immediately got hot and built a 6½-game lead by the end of July. Risberg had returned to the lineup by then and played well enough to remain as the starting shortstop for the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds.

In September Risberg received good press in the Atlanta Constitution, which labeled him a “miracle man (who had) blossomed out as a wonder.” More than one big leaguer, according to this article, claimed that Risberg possessed the “greatest throwing arm of any infielder in the big show,” boasting “almost unbelievable speed.”14 Manager Gleason offered his own assessment in the New York Times that month, stating with as-yet-unknown irony that Risberg might end up being the “star of the show” in the coming World Series.15

Darker undertones, however, stalked Risberg and the White Sox during the 1919 season. The team was split into two factions – the more educated players, led by second baseman and team captain Eddie Collins; and the more rough-and-tumble group, led by former boxer and current first baseman Arnold “Chick” Gandil. Risberg, who belonged to the second group, agreed to throw the 1919 World Series in exchange for payoffs from gamblers. In addition, he assisted Gandil in organizing the scheme, collecting money from the gamblers, delivering it to teammates, and helping to persuade Joe Jackson to participate. Jackson later said in a deposition that when he didn’t receive his promised money, he had threatened to expose the plot. Risberg threatened to kill Jackson if he blabbed, and was convincing. “Swede,” Jackson said, “is a hard guy.”16

Risberg took home a reported $10,000 to $15,000 for his role in the conspiracy.17 He also sent a telegram before the Series to his friend, St. Louis Browns infielder Joe Gedeon, informing Gedeon that the Series was fixed and advising him to bet on Cincinnati.18 A year later Gedeon informed on Risberg to the White Sox, hoping to collect a $20,000 reward offered by Charles Comiskey for information on the fix. Gedeon didn’t get the reward, but he was later banned from baseball for his prior knowledge.

Risberg played horribly in the Series, hitting only .080 (2-for-25) and making four errors. His involvement in the fix was solidified in Game One, when he failed to complete a critical double play in the fourth inning and the Reds went on to score five runs off White Sox ace Eddie Cicotte.19 In Game Six Risberg almost single-handedly eliminated his team from the World Series. He lined into two double plays (both times with a runner in scoring position), booted a grounder, and made an errant throw to allow a run to score. But his fellow conspirator Chick Gandil singled in the winning run in the 10th inning to keep the White Sox alive. Perhaps to cover up for the reasons behind his poor performance, Risberg claimed to have a cold during the Series. In the 1921 criminal trial, a team trainer testified that he had indeed given Risberg cold medicine before Game One.20

Risberg and the other suspected players (except Gandil, who had retired in a contract dispute) returned to the White Sox in 1920. Despite persistent rumors that the White Sox were continuing to throw games during the pennant race, Swede had his best season yet, batting .266 and setting career highs with 21 doubles, 10 triples, and 65 RBIs. He missed some time with a spike wound in May and then abruptly left the team in June, going home to San Francisco for two weeks, reportedly because his toddler son, Lawrence, was ill.21 Down the stretch, with dark clouds swirling over the White Sox, Risberg had some of the best performances of his career. He hit .380 in his final 13 games, including consecutive four-hit games on September 20-21 against the Philadelphia A’s as the White Sox tried to keep pace with the Cleveland Indians for the AL lead.

But one week later, Eddie Cicotte appeared before a Chicago grand jury and confessed to throwing the World Series. He was immediately suspended by owner Charles Comiskey, and so were Risberg, Gandil, Joe Jackson, Happy Felsch, Fred McMullin, Lefty Williams, and Buck Weaver. They were later acquitted in court, but none of them ever played in Organized Baseball again. A day after the jury’s verdict came back, Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis banned them all for life.

That didn’t mean Risberg – the youngest of the expelled Black Sox at 26 – stopped playing ball. Throughout the following decade, he traveled around the country and even into Canada, making a living in “outlaw” and semipro leagues, sometimes with his old teammates. Risberg did comparatively well playing outlaw ball; his son Robert later claimed that his father earned more money playing in outlaw leagues than he ever had playing for Comiskey.

His wife of nearly a decade, the former Agnes Garibaldi, who hailed from the same San Francisco neighborhood as the Risbergs, wanted no part of his nomadic lifestyle; in 1922 she filed for divorce, citing cruelty and neglect. In court Agnes stated that the couple had been happy when Risberg was playing in the Pacific Coast League, but not during his major-league career. As for the game-fixing scandal, Agnes said that Risberg grew fond of saying, “Why work when you can fool the public?”22 The divorce was granted in December 1922 and Agnes received custody of their two children, Charles and Lawrence. Her request for alimony was denied, however, because Swede had fled the jurisdiction of the court.

During that same summer of 1922, Risberg joined Cicotte, Williams, Weaver, and Felsch on a traveling team known as the “Ex-Major League Stars.” They scheduled a series of games against teams from northern Minnesota’s Iron Range, but lackadaisical play and poor management meant the players left with only a few hundred dollars afterward. Cicotte left the team in mid-June after an argument with Risberg over money – the hard-nosed Swede reportedly responded by punching him in the mouth.23

Risberg moved on to Minnesota, where he married a woman from Rochester, Mary Frances Purcell, with whom he had two sons, Robert and Gerald. In between his travels with the independent Rochester Aces team, Swede also operated a small farm for several years, selling eggs and other wares to the nearby Mayo Clinic to supplement his baseball income. With the Aces, Risberg used his strong right arm to return to his roots as a pitcher and he dominated the regional semipro competition. In 1923 he threw a no-hitter against a team of Minnesota collegians and struck out 21 batters in a game against a town team from Rice Lake, Wisconsin.24 Semipro pitchers were able to command higher salaries and under-the-table bonuses for high strikeout totals, so Risberg took the mound as often as his arm would allow for the rest of his “outlaw” career.

In 1926, Judge Landis contacted Risberg to garner testimony about a gambling scandal involving Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker. Although he had nothing to add to that case, Risberg (with the help of Chick Gandil) made national headlines by suggesting that in September 1917 the Detroit Tigers deliberately lost four games to the White Sox, helping Chicago capture the pennant. Two weeks later, Risberg added, he and Gandil collected $45 each from White Sox players, and forwarded the money to players in Detroit. Landis called dozens of players from both teams to his Chicago office to testify about the “new” baseball scandal. All of the other former White Sox and Tigers players contradicted their story, claiming that the money was paid out to Detroit players as a reward for winning late-season games against the Boston Red Sox, Chicago’s chief rival for the pennant. The practice of “rewarding” opponents was common during the Deadball Era, but Landis quietly banned it and cleared the Tigers of any wrongdoing. Will Rogers attended Risberg’s hearing and, in his view, “It was just that bottled up hate against everything that made [Risberg] think he hadn’t had a square deal in the game, and he exaggerated the incident.”25

Risberg stayed out of the spotlight afterward, but continued to play ball until the mid-1930s. He and Happy Felsch spent a summer playing for a mining company team in Scobey, Montana, and then toured western Canada together for a while, playing games against all challengers in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. During the Great Depression, he played for teams in Jamestown, North Dakota, and Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and also tried his hand at many other businesses (among them a car dealership, a hotel, and a miniature-golf course) as his ability to make a living in “outlaw” baseball subsided. Struggling to make ends meet, Risberg decided to move back home to Northern California, eventually settling in a town called Weed near the Oregon border. After finally retiring from baseball, he operated a successful tavern there for almost two decades.

Author Eliot Asinof, working on the book that became the classic Eight Men Out, visited Risberg at his tavern in the early 1960s. He described the nearly 70-year-old ballplayer as “balding and gray, his pale face relatively free of creases.” When approached, Risberg “seemed pleasant enough, although uninterested, as if sensing there was nothing in it for him.” Once Risberg realized Asinof’s intent to interview him, though, “His look was so cutting, so full of suspicion,” and Risberg claimed not to remember anything about the infamous events that had transpired so long ago.26

In his later years, Risberg’s health suffered as he developed osteomyelitis in his knee. The condition, which was supposedly caused by an old spike wound and possibly exacerbated by a bad car accident in Jamestown, forced Risberg to walk with a pronounced limp. The leg eventually became infected and had to be amputated. By this time, his wife, Mary, had died and Swede had moved in with his son Robert and family in Red Bluff, California, where he spent the final years of his life. In 1970 the local newspaper asked him to analyze the coming World Series between the Baltimore Orioles and Cincinnati Reds. He picked the Reds to win.27 (The Orioles won in five games.)

Risberg died on his 81st birthday, October 13, 1975, in a convalescent home in Red Bluff; he was the last of the “Eight Men Out” to die. He was buried next to Mary in Mount Shasta, California.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015). This biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006).

Sources

Asinof, Eliot. Bleeding Between the Lines (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1979).

Cottrell, Robert C. Blackball, the Black Sox and the Babe: Baseball’s Crucial 1920 Season. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002).

Muchlinski, Alan. After the Black Sox: The Swede Risberg Story (Authorhouse, 2005).

Seymour, Harold. Baseball: The Golden Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Atlanta Constitution

Baseball Magazine

Chicago Tribune

Los Angeles Times

New York Times

Red Bluff (California) Daily News

The Sporting News

Washington Post

Notes

1 Los Angeles Times, June 1, 1917.

2 Red Bluff (California) Daily News, October 9, 1970.

3 See the SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee newsletter for June 2012 at SABR.org. Historian Bob Hoie also noted that Swede had fine penmanship, a sign that “he was taught, and taught well.”

4 Los Angeles Times, March 29, 1912.

5 Atlanta Constitution, September 14, 1919.

6 Los Angeles Times, May 7, 1916.

7 Los Angeles Times, June 25, 1915.

8 Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1915.

9 Los Angeles Times, August 6, 1916.

10 Los Angeles Times, June 1, 1917.

11 Washington Times, September 27, 1917.

12 Chicago Tribune, May 23, 1918.

13 Bob Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Spring 2012).

14 Atlanta Constitution, September 14, 1919.

15 New York Times, September 28, 1920.

16 Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1920.

17 Ibid.

18 Tipped off by Risberg about the fix, Joe Gedeon reportedly won $600 betting on the World Series through St. Louis gamblers Carl Zork and Ben Franklin. See Washington Post, October 27, 1920.

19 The botched double-play ball, hit by the Reds’ Larry Kopf and fielded by pitcher Eddie Cicotte, remains one of the most disputed plays in the 1919 World Series. Some writers suggested that Cicotte’s throw to Risberg at second base was too low or too slow, while others thought Risberg delayed his throw to first, enabling Kopf to beat it out. The Chicago Tribune called it the “break of the game,” as the double play would have ended the inning and kept the game scoreless. A rare newsreel film discovered decades later and made public by the Library and Archives Canada in 2014 actually shows footage of the controversial play. See Jacob Pomrenke, “Rare Footage of 1919 World Series Discovered in Canadian Archive,” SABR.org, May 2, 2014, http://sabr.org/latest/rare-footage-1919-world-series-action-discovered-canadian-archive.

20 New York Times, July 29, 1921.

21 Chicago Tribune, June 14, 1920.

22 Duluth (Minnesota) News Tribune, August 28, 1922.

23 Chicago Tribune, June 25, 1922.

24 Stew Thornley, Baseball in Minnesota: A Definitive History (St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2006).

25 Indianapolis News, January 22, 1927.

26 Eliot Asinof, Bleeding Between the Lines (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1979), 92.

27 Red Bluff (California) Daily News, October 9, 1970.

Full Name

Charles August Risberg

Born

October 13, 1894 at San Francisco, CA (US)

Died

October 13, 1975 at Red Bluff, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.